Sebastião Salgado: Portraits of Pain and Dignity

By Trude Bennett

Volume 25, no. 2, Bleeding Earth

Perhaps the most internationally renowned visual documentarian from the Global South, Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, seventy eight years old, always wanted to ease the world’s pain. The cattle farm where he grew up with his parents and seven sisters in the Rio Doce Valley of Minas Gerais state in southeastern Brazil was 60 percent rainforest. Leaving home at age fifteen to attend secondary school and then university, he witnessed the beginnings of Brazil’s industrialization, quickly grasped the complexity of the larger world, and met his life partner and collaborator Lélia Wanick.

Together, they became activists and joined a leftist movement called Ação Popular (Popular Action) after a US-supported military coup in 1964 ushered in a two-decade-long dictatorship. Soon, they saw comrades arrested, tortured, and killed in the name of “national security.” The couple left for Paris and began graduate studies in exile—architecture for Lélia and development economics for Sebastião. Employed by the International Coffee Organization, he began travels to sub-Saharan Africa as a consultant to the World Bank but quickly became disillusioned with neoliberal economics. Equipped with Lélia’s camera, he was enchanted with the natural beauty and power of African landscapes. True to his own nature, he turned to photography to share his breathtaking observations of physical, animal, and human geographies.1

Back in Paris, he joined a series of photographic agencies; his longest affiliation was with Magnum Photos for fifteen years before the Salgados established their own press agency, Amazonas Images, in 1994. In addition to managing Amazonas Images, Lélia Salgado applied her skills as an architect and urban planner to conceptualize and organize Sebastião’s thematic photographic projects. She also managed their Paris household and care of their two sons while he embarked on travels of deep immersion to over 120 countries; she then oversaw the design, editing, and publication of the resulting books and the planning of exhibitions.

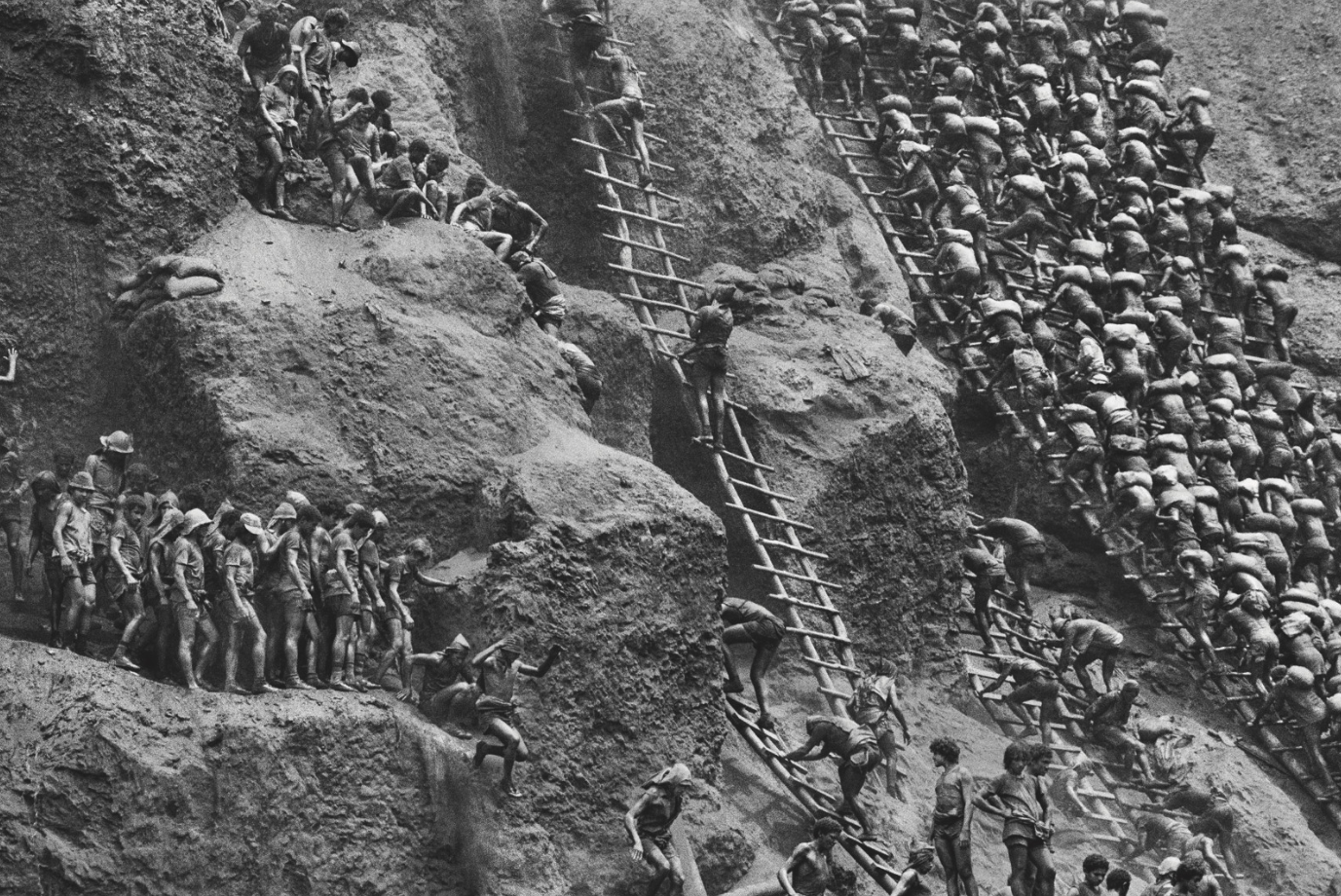

Sebastião Salgado’s photographic journeys have ranged in length from several months to seven years as his skill developed and his imagination flourished. These projects yielded astonishing black-and-white images, now published in multiple books. Salgado’s best-known photographs are depictions in Gold of the Serra Pelada goldmine in Brazil. Two hundred and seventy miles below the mouth of the mighty Amazon River, Serra Pelada was the site of a massive and chaotic gold rush in 1980–1986. Typical reactions on first viewing the photos are wonder and anxiety, like seeing a sixteenth-century Pieter Bruegel the Elder painting for the first time, encountering a massive anthill, or viewing an intricate abstract design that slowly resolves into a representation of torturous human activity—strenuous, precarious, and deadly dangerous.

Salgado’s Gold series testifies to the scale and speed of the expansion of the extractivism industry in Brazil. The historical narrative unfolds as follows: after a child discovered a gold nugget on a farmer’s property in the village of Serra Pelada, a geologist verified a huge deposit of gold at the site. Thousands of seekers rapidly swarmed the area, lured by some remarkable finds (the largest nugget weighing fifteen pounds).2 A cooperative quickly formed, and the original members assigned plots to subsequent arrivals (who were called “capitalistas”) and their investors. Others vied for the chance to dig and carry soil for the capitalistas. With thirty men working on each 6.6-by-9.8-foot plot, the pit was a buzzing hive of fifty to one hundred thousand tightly packed bodies at any given time. Landslides were common, and falls could be fatal. Loaded with ninety-pound sacks of muddy soil, men navigated wooden ladders to reach the top of the pit and then leapt like mountain goats back to the bottom. At the end of the day, carriers were allowed to choose and keep one of their sacks. Very few won this death-defying lottery; less than 1 percent of the sacks yielded any gold. For their eleven-hour working days Monday through Saturday, the workers earned subsistence wages along with basic food and shelter.

As the mania grew, Brazil’s military government put the mine under the supervision of federal police. Alcohol, women, and guns were banned at the site during the gold rush; but the contraband was simply relocated to a neighboring town, where wildness reigned with gold as currency, and murders were frequent. Officially, at least thirty tons of gold valued at four hundred million dollars came out of Serra Pelada; much more may have been smuggled. The lust for gold infected some so badly that they extended their quest—and much destruction—into the Amazon jungle. Truly, these incursions are the tailings of colonialism. Salgado found himself both awed and bewildered by the “gold fever” that has possessed people ranging from centuries of prospectors for precious metals to the contemporary ranks of cryptocurrency miners.

Many of Salgado’s black-and-white photographs in Gold capture intricate tableaux of workers arrayed in patterns that allow for massive execution and repetition of labor. In some of these photos, the individuals do not seem to have any contact with each other as they perform a kind of clockwork motion. And yet, their lives and livelihoods depended on their intimate coordination. We see miners single-mindedly panning for gold with joyless intensity and tempers boiling over with accumulated stress. Individual portraits are stunningly alive and unique. Take for example a snapshot of an individual carrier reaching the top of a ladder to begin the task of soil collection, his face obscured by the empty sack draped over his head and shoulders, his muscular body balanced in sure-footed motion. Only occasionally do we see workers at rest in the mine’s terrifying heights and depths, drenched in sweat and coated with dirt. Briefly unlocked from their toil, their faces show great curiosity in the camera and the photographer.

Inevitably, the images of the Serra Pelada and other photographs captured by Salgado’s camera have been subject to the standard “voyeurism” critique, central to conversations about photojournalism. Susan Sontag dubbed Salgado “a photographer who specializes in world misery” and thus “encourages hopelessness …” She belittled his work by decrying its “cinematic” quality, denying the photo’s ability to genuinely move viewers against violence and dispossession captured in the frame.3 To the contrary, Coleman and James suggest that “the camera … can enable a critical understanding of capitalist relations of production, of the constructed nature of social worlds, and of feelings that mobilize groups to act in concert.”4 With this assertion, Salgado’s photographs become, again, essentially political. The great Uruguayan writer, Eduardo Galeano, an admirer of Salgado, disdained accusations of a “tourism of poverty.” He wrote in eloquent praise that “Salgado’s photographs, a multiple portrait of human pain, at the same time invite us to celebrate the dignity of humankind. Brutally frank, these images of hunger and suffering are yet respectful and seemly. … they do not violate but penetrate the human spirit in order to reveal it.”5 Indeed, for Salgado, the solidarity he expresses in his work is a kind of acknowledgment of the gifts he gratefully receives from his subjects—the exact opposite, in fact, to the brutal extraction of products and labor that he portrays.

Salgado’s photographs operate in accordance with the immediacy of the moment; but they also work as an archive, offering historical testimony. After the end of the military dictatorship in 1985, Brazil’s new constitution mandated protection of 26 percent of the Amazon region for exclusive use by its original inhabitants. But the Amazon rainforest, “the lungs of the world,” is still and again seriously endangered.

The mine at Serra Pelada was closed by the government in 1986 due to severe structural hazards and then flooded to prevent further invasion and exploration. The concession was transferred back to the Companhia Vale do Rio Doce mining company in 1992. Today the area is stagnant, the former pit transformed into a mercury-laden lake 459 feet deep.

By 2004, the coastal Brazilian (Mata Atlantica) rainforest covered only 7 percent of the area existing in the 1940s and 0.3 percent of its original size in the region of Salgado’s birth.6 Brazil’s right-wing president, Jair Bolsonaro, greatly accelerated deforestation and removed protections from the Amazon and its Indigenous residents.7 According to a November 2021 estimate by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research, deforestation—both legal and illicit—increased by almost 22 percent in the previous year.8

The photographs at Serra Pelada were intended not as a stand-alone effort, but rather a segment of the long-term project that became Workers: An Archeology of the Industrial Age. The power of the Gold photographs, however, captured both artistic and popular imaginations and reinvigorated the status of black-and-white photography at a time when color was in ascendancy.

Salgado’s career was long and his projects varied, covering famine, war, and human suffering. In 1994, he returned to Paris, traumatized, physically ill, and severely depressed from witnessing and documenting the Rwandan genocide. When his belief that he was actually dying was medically confirmed, the family decided to return to Brazil in hopes of finding peace and comfort. Instead they discovered the family land devastated by slash-and-burn agriculture, deforestation, and severe drought.

Bold and creative as always, Lélia proposed an ambitious scheme of reforestation—a project that allowed Sebastião to recover his health and build for the future. After decades of experimentation and replanting three million trees of three hundred different species, the lush area is once again thriving with dense layers of plants and abundant wildlife. Salgado donated his ancestral land to the State for a national park and nonprofit nursery devoted to environmental education and training.9

Except for assignments in the early days, Salgado’s projects have been self-defined. He is guided by a dual goal, balancing the desire to record contemporary realities before the inevitable onset of change while mobilizing human effort to prevent destruction and disaster. Although Salgado is not an ideologue and speaks most prolifically with his camera, his passion for change and renewal is not far from his Marxist roots. One can tell a lot about Salgado’s intentions from the simple titles of his major photographic collections, e.g., Migrations (2000), Workers (2012), Genesis (2103), Kuwait (2016), Gold (2019), and Amazônia (2021).

“Humanity is capable of understanding, even controlling, the political, economic, and social forces that we have set loose across the globe.”

A close look at some of these works reveals the depth of Salgado’s understanding of how colonial heritage, neocolonial domination, and globalized capitalist extraction could be revealed, for example, in burning oil fields in Kuwait, parched earth in the Sahel, and depleted rivers in Mexico. The human portraits are bathed in dignity and respect, but their poignancy shocks the viewer into an awareness that questions the forces at play. A step back reveals the tangled intersections of stories behind the pictures—wars fought over extraction of oil, gas, and minerals; climate change caused and exacerbated by extractive industries; labor under dangerous and deadly conditions in those industries; and migration spurred by conflict, environmental depletion, and extreme weather events.

As Galeano observes, “These images that seem torn from the pages of the Old Testament are actually portraits of the human condition in the twentieth century, symbols of our one world, which is not a First, a Third, or a Twentieth World. From their mighty silence, these images, these portraits, question the hypocritical frontiers that safeguard the bourgeois order and protect its right to power and inheritance.”10

In his essay at the beginning of Migrations, Salgado confesses that neither the challenges of his earlier projects nor his political beliefs prepared him for the cruelties he witnessed globally, though migrants’ trust, resilience, and desire to be heard and represented felt heroic to him. Disillusioned with existing political realities, he makes a plea for revolutionary honesty and recognition of our world’s interconnectedness. He denounces spectatorship and believes “humanity is capable of understanding, even controlling, the political, economic, and social forces that we have set loose across the globe. Can we claim ‘compassion fatigue’ when we show no sign of consumption fatigue? Are we to do nothing in face of the steady deterioration of our habitat, whether in cities or in nature? Are we to remain indifferent as the values of rich and poor countries alike deepen the divisions in our societies? We cannot.”11

Sebãstiao Salgado is like a sensitive instrument that vibrates in tune with what he is viewing and experiencing. He has a lifelong belief in collectivism, having observed that “individualism remains a prescription for catastrophe. We have to create a new regimen of coexistence.”12

In a program on climate at the International Center of Photography on April 24, 2022, Salgado stressed the necessity of solidarity, collaboration, and community with all forms of life on the planet. “Alone is nothing—my work alone accomplishes nothing. … Inside a flow of information, inside a community—working together is important, inside a movement using different media, together [we] can be very powerful. … You do things because you are part of the society you live in, to know people and planet.”13

When asked about his importance or meaning for future generations, he startled his audience by declaring: “I never think about future generations. Now my photography can be used to provoke the discussion and find the solution … linked with the Indian movement … the environmental movement. Photography alone is peanuts; with other movements, it’s important.”

Notes

- Anthony Feinsten, “Humanity’s Spirit and Cruelty: Sebastiao Salgado in Focus,” The Globe and Mail, September 21, 2015, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/humanitys-spirit-and-cruelty-in-focus/article26454376/.

- “The Hell of Serra Pelada Mines through Photographs, 1980s,” Rare Historical Photos, November 10, 2021, https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/hell-serra-pelada-1980s/.

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 78–80.

- Kevin Coleman and Daniel James, Capitalism and the Camera: Essays on Photography and Extraction (New York: Verso Books, 2021), 30–31.

- Eduardo Galeano, “Introduction,” in Sebastião Salgado: An Uncertain Grace, eds. Sebastião Salgado and Robert Ryman (New York: Aperture, 2005).

- “Biography: Sebastião Salgado,” The Guardian, September 11, 2004, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2004/sep/11/sebastiaosalgado.photography2.

- Dom Phillipis, “’Like a Bomb Going Off’: Why Brazil’s Largest Reserve is Facing Destruction,” The Guardian, January 13, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jan/13/like-a-bomb-going-off-why-brazils-largest-reserve-is-facing-destruction-aoe.

- Emma Bowman, “Amazon Deforestation in Brazil Hits Its Worst Level in 15 Years,” NPR News, November 19, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/11/19/1057245837/brazil-amazon-rainforest-worst-deforestation-rate.

- McKenzie Funk, “Sebastião Salgado Has Seen the Forest, Now He’s Seeing the Trees,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2015, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/sebastiao-salgado-forest-trees-180956620/.

- Galeano, “Introduction.”

- Sebãstiao Salgado, Migrations: Humanity in Transition (New York: Aperture Foundation Inc., 2000), 14.

- Salgado, Migrations, 15.

- Sebãstiao Salgado, “ICP Infinity Talk—On Climate,” International Center of Photography, New York, April 24, 2022.