The Battle of BP and the Bucket Brigade

By Zak Lakota-Baldwin

Volume 25, no. 2, Bleeding Earth

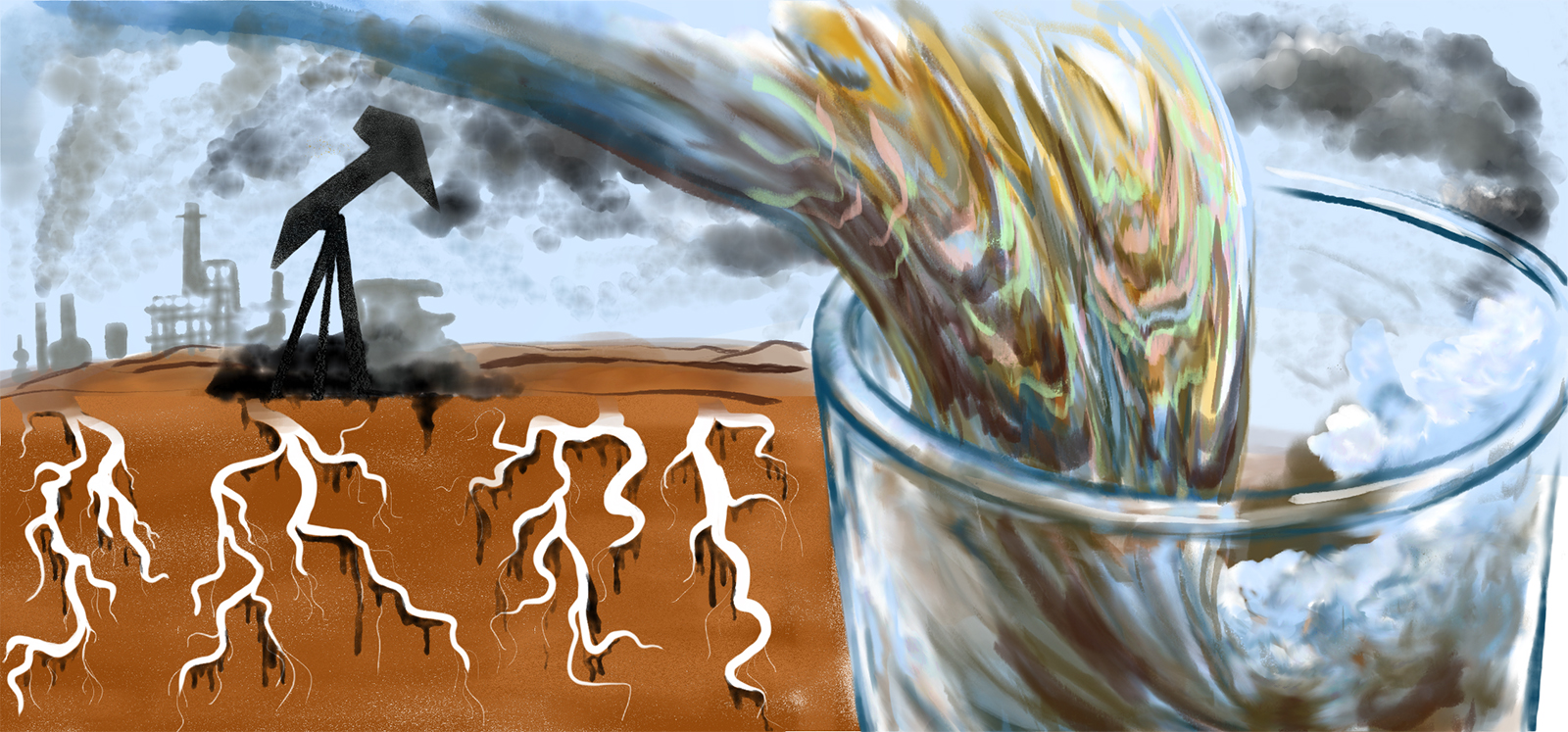

Few environmental disasters are more notorious in the West than the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The name evokes grim, apocalyptic images: plumes of fire and thick smoke above the ocean; dark, shimmering slicks lying heavy on the water’s surface; seabirds choked in sticky tar, their feathers matted and eyes glazed. It amounted to, by far, the biggest oil spill in American history, with catastrophic consequences for both the human and non-human denizens of the Gulf Coast. Deepwater Horizon is most commonly remembered for this sheer scale of devastation, and for the institutional failures and culture of risk-taking within BP that led to the spill. There is a tragically familiar story of negligence, corporate greed, and disregard for nature to be told here, but it belies another story which has received far less attention: that of the various concerned citizens, activist groups, and environmental non-profits that responded to the spill as it unfolded. Dissatisfied with the limited scope of official spill monitoring efforts and frustrated at BP’s dogged attempts to downplay the severity of the disaster, many people in and around the Gulf Coast took part in citizen-led initiatives to measure and publicize the full extent of the spill’s impacts on their lives. Using citizen science methods such as crowdsourced online maps and improvised aerial photographic devices, these groups were able to challenge expert assessments of the spill and magnify the voices of those most affected by it.

In the US South, which bore the brunt of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, it is largely poor people and people of color who make up the fenceline communities situated alongside the numerous refineries, chemical plants, and landfill sites that represent such a large part of the region’s economy. These fenceline communities, constantly bombarded with toxic chemicals and carcinogens from the polluting industries on their doorsteps, have been at the forefront of battles to improve regulatory standards and push back against discriminatory siting practices. Therefore, although an oil spill from an offshore rig was a new kind of crisis, communities in the South were all too familiar with the challenges of having their experiences of pollution and environmental exploitation taken seriously by corporations and government authorities.

One of the methods employed by these communities has been citizen science,1 collecting their own data on issues such as air pollution and illness, and using it to contest official studies that often fail to account for the embodied knowledge of those affected. Though citizen science in this context comes with its dangers, such as the potential transformation of a multifaceted sociopolitical issue into a narrow technoscientific problem of measurement and standards, it has often been a powerful tool to effect change and draw public attention to further struggles.2 This is particularly true of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade (LABB), an environmental justice organization dedicated to supporting the predominantly poor, Black fenceline communities of Louisiana by training them to use low-cost, DIY air quality sensors to make legal challenges against the petrochemical companies polluting their neighborhoods. Formed in 2000 from an amalgamation of local air quality monitoring groups, LABB’s history of community organizing and activism within this region long burdened by environmental racism meant that it was well-placed to respond immediately and effectively to the BP oil spill in 2010. Through LABB’s open-source “Oil Spill Crisis Response Map,” members of the public were able to record oil and dispersant-related exposures and various other spill impacts into a centralized database. Many of these reports were anecdotal testimonies detailing how people’s lives had been affected, providing much-needed context and grounding to the reams of impersonal official data on the oil spill. The map gained substantial traction: it received thousands of submissions, featured widely in national media, and was considered in federal-level proceedings.3

Despite the great impact of their work during the spill, these activists and citizen scientists have largely been invisible in retrospective accounts of Deepwater Horizon, other than to appear as passive victims with none of the power and agency afforded to oil executives, government scientists or federal politicians. In telling their story here, it is vital not to make the same mistake by privileging the role of the technology itself; this was a battle fought by people, not maps, and the success of the citizen science intervention was only possible because LABB already had deep ties with some of the affected communities and made proactive efforts to engage others. The work of LABB shows that citizen science is not necessarily a means to democratization and justice in and of itself, but must be community-led rather than imposed from the top down, and focused on radical, grassroots aims beyond just the production of better monitoring technologies and the collection of better data. The challenges faced by LABB also demonstrate the difficulty of bringing attention to the often insidious and unseen violence of pollution, and of maintaining engagement and activism outside of the context of a highly-publicized environmental disaster. It is important to ask what role citizen science can play in this ongoing struggle, one which is fundamentally rooted in issues of class and race yet so often reduced to mere numbers or ignored entirely.

The Roots of Resistance

The American South, where the Deepwater Horizon oil spill made its landfall, has a history of pollution and environmental exploitation that far predates the 2010 disaster. This impoverished region became a major industrial growth center in the 1970s and 1980s, due to a number of factors including weak labor unions, strong right-to-work laws, cheap labor and land, and lenient environmental regulations. Polluting industries seized upon this opportunity, and the South filled with petrochemical refineries, garbage incinerators, hazardous landfills, and toxic-waste dumps. A disproportionate number of these facilities were sited in close proximity to poor communities and communities of color, as these groups lacked the power and resources necessary to offer organized resistance. Citizens who expressed concerns about the environmental risks were initially silenced by arguments from local politicians and industrialists emphasizing the greater importance of job creation. Over time, however, the overburdening of poor and minority communities with pollution and toxicity gave rise to what is now called the environmental justice movement.4 This movement is generally accepted to have originated from communities of color in the Deep South in the 1980s, with the 1982 protest by Black community members in Warren County, North Carolina against the siting of a toxic PCB landfill frequently cited as a foundational event.5 As the convergence of social justice activism and traditional environmentalism, the environmental justice movement opposes pollution in the places where it affects the most marginalized communities.

Louisiana is home to an 85-mile industrial corridor along the Mississippi River, commonly referred to as the “chemical corridor” or “cancer alley.”

The Louisiana Bucket Brigade emerged as part of this movement, in a state where the environmental situation was especially dire. Louisiana is home to an eighty-five-mile industrial corridor along the Mississippi River, from Baton Rouge to New Orleans, which at its height in the 1980s was producing one quarter of America’s petrochemicals.6 This stretch, commonly referred to as the “chemical corridor,” is also known by environmentalists as “cancer alley” because of the chronic health problems experienced by the predominantly poor, Black communities who have lived within the area since the end of the Civil War.7 These fenceline communities bore the cost of the Louisianian economy’s heavy dependence on the petrochemical industry, experiencing disproportionately high rates of illness and learning to “fear the very place they call home.”8

This fear did not end in passive acquiescence, however. One of the tools adopted by some of these communities was an air-monitoring “bucket” originally designed by environmental activists in California. The bucket served as a cheap alternative ($75) to the Summa canisters ($2000) used by government and industry for air testing, allowing concerned citizens to sample their air and detect the presence and concentration of various toxic gases, thus lending empirical support to anecdotal claims of excessive and unlawful exposure. This practice was first used by a group of Mossville residents in Louisiana’s chemical corridor, who in 1998 formed their own bucket brigade and took air samples to reveal violations of Louisiana standards for vinyl chloride, EDC and benzene. During the ten years preceding the Deepwater Horizon spill, LABB worked with fenceline communities throughout the state on various environmental justice campaigns. They achieved a number of modest victories, such as a Shell buyout of contaminated property in Norco and a reduction in the accident rate of a refinery in New Sarpy.9 These campaigns and initiatives, though not radically transformative in their outcomes, nonetheless made tangible and measurable impacts within Louisiana’s fenceline communities.

A few weeks before the Deepwater Horizon rig erupted in flames, Anne Rolfes (the founding director of LABB) had been working on a new citizen science project: an online platform for visually mapping out crowdsourced reports of environmental hazards at the state’s numerous petroleum refineries. When the news emerged of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Rolfes quickly realized that LABB’s fledgling crowdsourcing platform could be utilized to help people respond to the disaster oozing towards their shores. Through this map, Gulf Coast residents were able to contribute their own situated perception of the risks and impacts of the spill to a centralized database, creating an aggregation of community experiences that could be used to challenge expert assessments of the spill and hold BP accountable for the full extent of the damage. Thus, although the object of concern was different—an oil spill from an offshore well rather than pollution from inland petrochemical refineries—the necessary tools and underlying principles were much the same, allowing LABB to apply its historical championing of people’s knowledge to the disaster presently unfolding.

Slow Violence

There is an important similarity between the harm inflicted on fenceline communities by petrochemical facilities in the chemical corridor, and the toll of the oil spill on communities throughout the Gulf Coast: it defies our conventional understanding of violence, as something immediate, explosive, and highly visible, and for this reason it was easier for institutional power to discount and ignore. Noting the different timescales of ecological harm perpetrated on the poor, Rob Nixon offers the concept of “slow violence” to encompass threats such as climate change, toxic drift, deforestation, and oil spills. Nixon defines it as “a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.”10 The challenge, argues Nixon, is to find a way to turn these slow moving disasters into stories that carry the necessary sense of urgency to draw public attention and compel political response. He cites the example of Ken Saro-Wiwa, a Nigerian writer-activist who was detained and subsequently executed in 1995 for his resistance to Shell and Chevron’s decades-long exploitation of the Ogoni people in the Niger Delta. In his detention diary A Month and a Day, Saro-Wiwa documented and brought global awareness to what he called the “deadly ecological war against the Ogoni,” a war in which the casualties came not only from the guns of the Nigerian military dictatorship but also the natural gas flares despoiling the air, the oil spills consuming the Ogoni croplands, and the toxic chemicals coursing through the streams.11

A burning oil rig makes for a compelling front-page image; out-of-work fisherfolk suffering from nausea and headaches do not immediately demand the same attention.

Saro-Wiwa’s story, and the broader struggle to which he belonged, is cited by LABB as the inspiration behind its formation. Anne Rolfes herself began her career in Benin documenting the stories of environmental justice activists who had been driven out of Nigeria for their resistance to the exploitative practices of the oil industry in the Niger Delta, before returning to Louisiana in 2000 and helping to form the bucket brigade. In its ten years of environmental justice activism before the oil spill, LABB used citizen science as a means of exposing slow violence and mobilizing action against it. Deepwater Horizon required the same approach: although the explosion of the oil rig was a moment of visible, overt violence, the slow-motion explosion that rippled through the Gulf afterwards took a more insidious form. A burning oil rig makes for a compelling front-page image; out-of-work fisherfolk suffering from nausea and headaches do not immediately demand the same attention.

This was precisely what made LABB’s efforts so valuable in tracking the impacts of the BP oil spill: although the Crisis Response Map included large amounts of quantitative data, many reports submitted were written testimonials, each anecdotal in nature but collectively giving voice to the risk perceptions and impact assessments of the Gulf communities in a way that uncontextualized numbers would have failed to capture. This anonymous entry to the map is illustrative:

My 3-year-old son was diagnosed with pneumonia on Monday morning. He was admitted to the hospital Monday afternoon and finally discharged Wednesday afternoon. He was a perfectly healthy and happy 3-year-old boy until this incident. I read that children have been susceptible to dispersant-related pneumonia. If this is true, I have a feeling that this was his problem, as he has had no significant health problems up to this point. He was in the hospital for three days, with the fourth day at home. I was, of course, by his side the entire time. Due to my being there with my son, I had to miss nearly a week of work.12

LABB’s history of environmental justice organizing had trained them to anticipate the gatekeeping role played by regulatory standards in legitimizing the bucket monitoring approach used by the citizens, even in the absence of obvious critiques towards the scientific validity of the approach.13 Accordingly, the strength of LABB’s use of citizen science during this crisis was its reframing of the problem as defined by authorities, so that the central question was not merely “how big is the spill?”, but a whole network of questions reflecting the priorities of the people impacted the most.

The map allowed respondents to submit reports in a wide variety of categories, far greater in scope than risk assessments produced by government agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). People could take note of issues ranging from odor, smoke and health effects to tainted seafood, threatened livelihoods and cultural loss, and even suggest solutions and ideas. Citizens were therefore afforded the opportunity to map the impacts of the crisis on their own terms, rather than relying on official assessments that inadequately captured the lived experience of the people on the frontlines of the spill. The Crisis Response Map also enabled the public to circumvent BP’s tight control of information: since reports could be submitted to the map anonymously, clean-up workers hired by BP were able to share their experiences despite being legally bound to silence, and were uniquely positioned to document spill impacts in areas which BP had cordoned off from the public and press.14

Challenges and Opportunities for Citizen Science

Though LABB was a veteran of numerous clashes with the oil industry, these clashes had largely played out in the battlegrounds of fenceline communities and petrochemical facilities along the chemical corridor. Offshore drilling, on the other hand, was not a familiar foe. In fact, the longstanding history of offshore oil development in Louisiana had unfolded in such a way that this industry enjoyed considerable support among the inhabitants of the state’s coastal regions.15 Since these were some of the people most heavily affected by the BP spill, LABB faced the challenge of engaging a new set of communities with a traditionally more positive disposition towards the oil industry.

LABB’s approach has been driven by a continued focus on the fundamental issues underlying its citizen science, remaining committed to fighting political battles that go beyond just the problem of standards.

LABB confronted this tension directly by taking a proactive approach and meeting people face-to-face, rather than merely waiting for reports to appear on the Crisis Response Map. LABB volunteers spoke to local fisherfolk, listening to their concerns in order to identify the areas most badly affected by the spill and putting them in touch with scientists who could take additional measurements. They also conducted hundreds of face-to-face surveys throughout the communities of southern Louisiana, measuring both health and economic impacts. Not everyone was interested in collaborating with LABB—some fisherfolk carried out their own sampling of seafood, resulting in “some disjointed citizen science efforts rather than a larger sense of social cohesion as often occurs in movements using citizen science.”16 For the most part, however, LABB was successful in moving beyond the communities it had historically been involved with and providing a platform for the people at the center of this crisis to vocalize the issues that mattered most to them.

The citizen science of LABB received extensive engagement outside of the immediate disaster zone too, becoming part of the national conversation around the spill. Yet this initial surge of engagement proved to be short-lived: once the oil well had been capped and the spill declared “finished,” it became far harder for LABB to command attention and articulate its more radical views beyond urgent, crisis-mode discourse. This is typical of a phenomenon observed by the Science and Technology Studies scholars Aya Kimura and Abby Kinchy in their 2019 book Science by the People: citizen science framed as disaster response can be very effective in gaining participants, supporters and funding in the short term, but breaking out of this limited timeline and converting the transitory momentum into long term work addressing the historic and systemic roots of the disaster is considerably more difficult.17

LABB made efforts to maintain its activism as national discussions around the oil spill began to die down: the group formed a new coalition called “The Oil Monitoring Group,” to train people to act as observers in publicly accessible oil industry meetings, and staged protests at auctions for offshore drilling leases.18 The Oil Spill Crisis Response Map was renamed the iWitness Pollution Map in 2012, to reflect its broader scope as a watchdog for the activities of the oil industry both in refineries and offshore. Amidst these ongoing battles, the challenge remains to find ways to continue publicly scrutinizing and resisting the slow violence caused by polluting industries with the same energy and far-reaching impact that characterized activism during the height of the BP oil spill.

Importantly, LABB’s approach has been driven by a continued focus on the fundamental issues underlying its citizen science, remaining committed to fighting political battles that go beyond just the problem of standards and the acceptance of citizen-derived data. Although much of the day-to-day work involves training community members to take air quality measurements and using the data to fight legal battles for better living or working conditions, the goal is a complete end to environmental exploitation and fossil fuel reliance, and this is always articulated through a lens that centers the radical societal changes needed to make this goal a reality. Citizen science can be a valuable tool for challenging expert assessments, creating community engagement and raising public awareness, but more data does not guarantee action and change. As groups like LABB demonstrate, these are hard-fought battles against often overwhelmingly powerful opponents, and when victories are won they are won by people—those belonging to the affected communities themselves, for whom these battles are a part of their lived reality and history. Remaining mindful of this is a crucial part of ensuring that citizen science can live up to its radical potential, and help bring us closer to environmental justice.

Notes

- There has been much debate about the term “citizen science,” with many justifiably taking issue with the problematic and exclusionary connotations of the word “citizen.” Recently, there have been efforts to adopt alternative terminology to describe instances where members of the public participate in the production of scientific knowledge, including “community science,” “tracking science,” and “street” science. See Caren B. Cooper et al., “Inclusion in Citizen Science: The Conundrum of Rebranding,” Science 372, no. 6549 (2021): 1386–1388 and Louis Liebenberg et al., “Tracking Science: An Alternative for Those Excluded by Citizen Science,” Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 6, no. 1 (2021). —Ed.

- Gwen Ottinger, “Buckets of Resistance: Standards and the Effectiveness of Citizen Science,” Science, Technology, & Human Values 35, no. 2 (2010): 244–270, https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243909337121.

- Sabrina McCormick, “After the Cap: Risk Assessment, Citizen Science and Disaster Recovery,” Ecology and Society 17, no. 4 (2012): 31, http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-05263-170431.

- Robert D. Bullard, Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class and Environmental Quality, 3rd ed. (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2000).

- Esme G. Murdock, “A History of Environmental Justice: Foundations, Narratives and Perspectives,” in Environmental Justice: Key Issues, ed. Brendan Coolsaet (London: Routledge, 2020), 6–17.

- Bullard, Dumping in Dixie.

- Barbara L. Allen, Uneasy Alchemy: Citizens and Experts in Louisiana’s Chemical Corridor Disputes (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003).

- Allen, Uneasy Alchemy, 27.

- “History and Accomplishments,” Louisiana Bucket Brigade, accessed July 20, 2021, https://labucketbrigade.org/about-us/history/.

- Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), 2.

- Ken Saro-Wiwa, A Month and a Day: A Detention Diary (London: Penguin, 1996).

- “Health Problems for My Three-Year-Old,” Oil Spill Crisis Response Map, July 2, 2010, http://map.labucketbrigade.org/reports/.

- Ottinger, “Buckets of Resistance.”

- Sabrina McCormick, “Transforming Oil Activism: From Legal Constraints to Evidentiary Opportunity,” in Disasters, Hazards and Law, ed. Mathieu Deflem (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2012), 113–131.

- William R. Freudenberg and Robert Gramling, Blowout in the Gulf: The BP Oil Spill Disaster and the Future of Energy in America (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), 129–138.

- McCormick, “After the Cap.”

- Aya H. Kimura and Abby Kinchy, Science by the People: Participation, Power, and the Politics of Environmental Knowledge (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press).

- McCormick, “Transforming Oil Activism.”