Review

A Future at the End of Time

By Nadine Fattaleh and Calvin Wu

Volume 25, no. 2, Bleeding Earth

Once upon a time, a Shepherd asks a Wiseman about the future on Earth. The Wiseman turns the question back: “Tell me what you’ve seen.”

The Shepherd describes: “I was searching for water, but nothing. I got thirsty and found a big tree. I went to rest under its shade. A huge tree, full of leaves, yet offers no shade. As soon as I saw this bizarre sight, I cried.”

The Wiseman explains: “That tree is the community at the end of time. When you plead for help, you’ll find that it needs more help than you!”

The Shepherd continues: “I also saw a carcass. On top were many doves, devouring it. Very clean doves, shimmering white.”

“That’s the state that will rule at the end of time. The state will have all the resources, but it’s a carcass: a body that has been thrown out, and there are some who eat from it.”

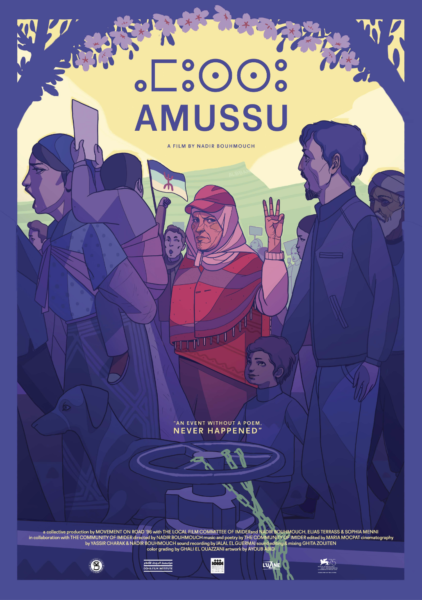

The parable of the Shepherd and the Wiseman is one story featured in Nadir Bouhmouch’s breathtaking documentary film, Amussu (2019). An elderly woman relays this tale where science fiction meets Amazigh oral traditions, while others prepare wool for weaving in the mountains of Imider in southeastern Morocco. The youngest girl of the group interjects for clarification. When is the end of time? The group explains that the end has already arrived: the end of time is now.

“The blossoms open, and can fall before giving fruit.”

Comprised of seven mountainous villages and around five thousand inhabitants, the Imider commune seems to be living at the end of time. Their community is under siege: they witness the state rotting in front of their eyes. Africa’s biggest silver mine is encroaching on their way of life. Everywhere they search they find water drying up—in fact, stolen—and not for the first time. They rise up to demand justice. And the name of the movement—Amussu :xf Ubrid n 96 Imider (“Movement on the Road ’96 Imider” in the Tamazight language)—is itself a salient reminder of the commune’s long struggle against extraction.1

While the premise of an Indigenous people fighting the juggernaut of mining capital and the repressive state is common throughout anti-extractivist documentary films, Amussu is unique in that the communards of Imider are not only the subjects of the story, they are themselves the storytellers. Collectively written, shot, compiled, and produced by the people, the film alternates between two primary settings. The first is in the Imider villages where life proceeds as usual: men harvest almonds in the oasis, women spin wool and bake bread in the huts, while children study or play in the alleyway. The portrayal of tradition that manifests in small everyday acts affirms Indigenous cultural identity and accentuates the impending cataclysm from capitalism’s homogenizing tendency.

Then there are scenes on the hilltop of Mount Albban, where communards gather at the fortress-like protest site, the longest running encampment in Moroccan history, overlooking the barren landscape in the distance. Contrasting the pristine desert is the water pipeline that traverses the hilltop and vanishes into the horizon. This is the camp’s raison d’être. The protesters are guarding the valve so that water would not supply the mine. As various individuals move to and fro between the villages and the camp, the audience listens to their stories through casual conversations, songs, and melodic chants.

“There should be no poor people on this land.”

The protestors are angry about the theft of water, pollution of the soil, and poverty in the face of extracted silver riches. They are fearful of harassment and arrests that have taken their friends and family away as the state attempts to break the movement. The film offers no chronology of the mine’s operations; neither does it focus on scientific accounts of environmental damage or statistical records that quantify the scale of extraction. From lived experience, it is well understood that as the water wells are dug deeper into the ground, the aquifers on which the community depends are further depleted. One elderly man briefly narrates the history of confrontations with the state-owned mining corporation since 1969, but the intergenerational cast of the film bear witness to the long lineages of struggle. The people of Imider reveal to the audience that they have always been fighting for justice. They talk about anti-extractivist protests in other parts of the country; they long for solidarity with international movements opposing neoliberalism and environmental destruction.

Between the minutiae of everyday life and the enormity of the political context stands the artful cinematography that invites the viewer to be imbued with the collective psyche of the commune. This is the expected result of a “people’s film,” which connects the reality of dispossession and the spirit of resistance to their class and cultural identity. As we borrow the eyes of a villager, immerse ourselves in their chants, prayers, and supplications, we also become observing members of Agraw: the commune’s governing body where all—that is, everyone—in the camp or the village joins in a giant circle. The ongoing protest transformed this age-old Amazigh tradition, which was reserved exclusively for men, into a modern demonstration of direct democracy that now includes both women and children.2 Perhaps the most iconic scene of the film that crystalizes the aesthetic of collectivism at Imider is a low-angled shot featuring a woman with a loudspeaker, which symbolizes their intimacy to the grassroots as well as the transitory nature of power. Discussions ranging from legal battles over arrest charges to the selection of photographs to be used in the film are all made in Agraw. It is the heart of “amussu” (movement), and the de facto producer of the film.

The collective nature of the film’s production and storytelling devices is an artifact of the movement’s democratic structure, and in part, a result of the “improvisational realism” demanded by a context that is heavily policed and surveilled by the government. There were never going to be film permits granted to Nadir Bouhmouch or the people of Imider by the state. In fact, “the entire film [was] shot in a guerrilla fashion,” as the people helped each other “hiding in houses, guiding through the bush to avoid police checkpoints, disguising equipment,” as well as counter-counterintelligence.3

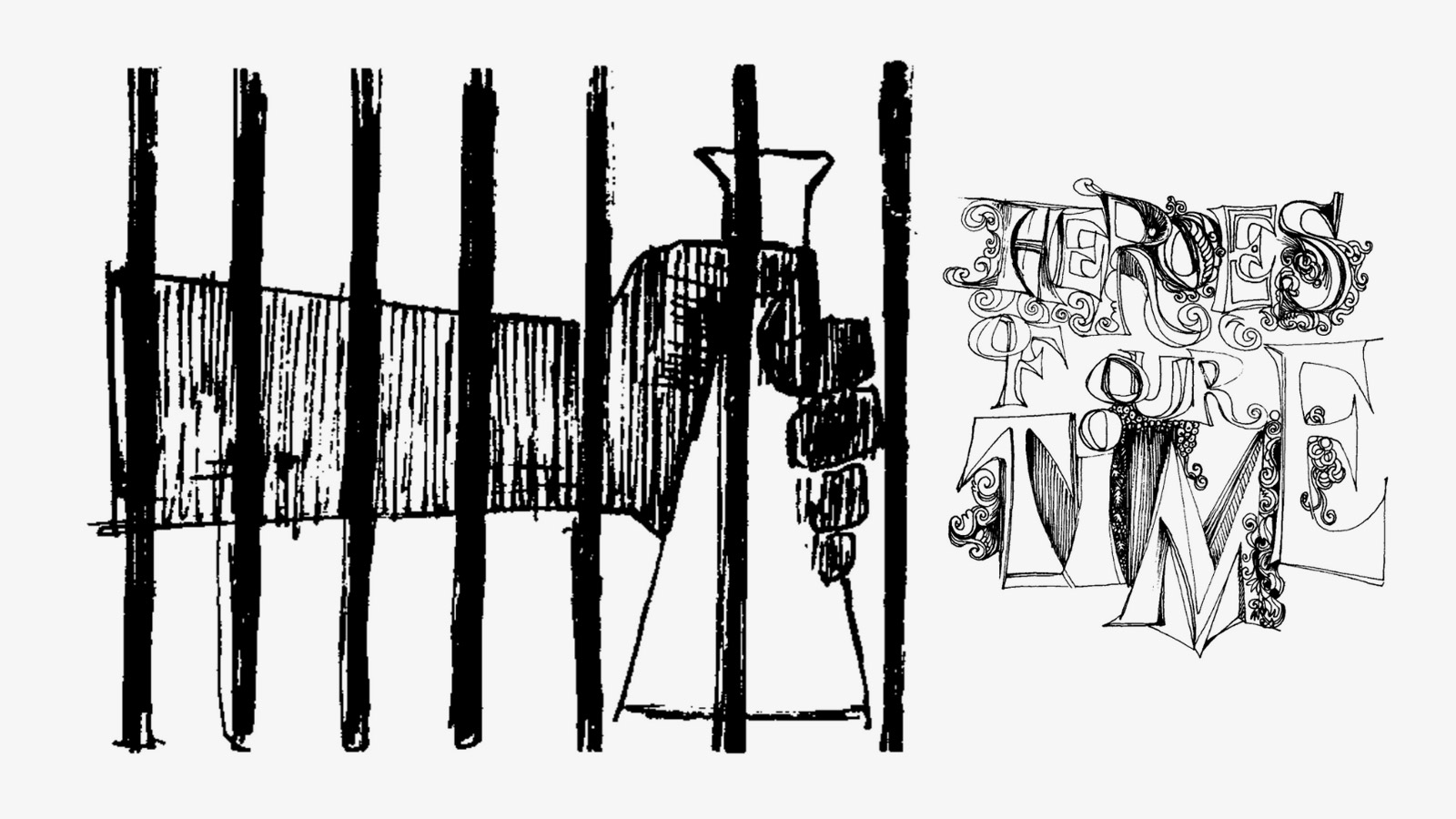

The film’s final innovation is the authenticity with which it relays the art forms, both folk and modern, that animate the struggle against the silver mine. The film features a shimmering array of art, from maps, murals, graffiti, and drawings that decorate the camp in Mount Albban, to formally organized film screenings, rehearsed theater performances, recorded indie music that assembles the community, and finally, the folk traditions of the elderly that include poems, chants, stories, and incantations.

Culture is at the heart of the protest, its forms are diverse and multiple; they proliferate and propagate a popular memory that is Indigenous, localized, and stands apart from the hegemonic metropolitan culture. Countless ethnographers, folklorists, and documentarians, of both a colonial and nationalist bent, have trodden the Atlas Mountains cataloging and quantifying the rich visual and verbal heritage of the Amazigh communities.4 The resulting “anthropological” register remains extractive: it inscribes an improvisational oral tradition into a fixed written text, it reduces intricate craft to the flattened surface of photographic images, and creates an ossified archive of a culture that is thought to be admirably stuck in the past. Amussu, instead, breathes life into a counter-archive of Amazigh tradition, where permeable cultural forms are constantly shifting and evolving. Chanting the struggle in a breathtaking repertoire of poetry, the film transmits the contingency of an oral culture against the backdrop of a vivid landscape that defines the topography of the spoken word, elucidating the context that necessarily shapes the contours of a radical, evolving, and oppositional tradition.

Oh mother! Tell them I have set up camp on top of Albban

Movement, Movement

On the road of the martyr,

The biggest school for militants.

Hand in hand,

We’ll break the chains,

We’re all one hand,

For the unity of Imider.

Imider, Imider

Is struggling in the Southeast,

For water, land, and a dignified life.

This collective autobiography is merely a snapshot of the movement in 2017, seven years into what was already at that time the longest protest in Morocco’s history. With the film’s modest publicity as well as Agraw’s push to join up with other anti-extractivist actions, amussu received international spotlight and had become a leading anti-capitalist voice of North Africa.5 But the forces they came up against were unrelenting; the double repression by state violence and poverty ultimately forced the Mount Albban camp to disband in 2019.

According to a hard-hitting postmortem, the “lack of clarity in vision and demands” as well as insufficient “rapprochement between the protesters and [mine] workers” doomed the struggle.6 But it is also worth noting that grassroots movements are always messy, with failures the norm, rather than successes, and it is by appreciating and transforming the process that future amussu can be created. The year 2019 will be immortalized by future communards as is the year 1996. And this is the heart of the film’s power. In documenting the myriad ephemera with intersecting moments of despair and hope, it enriches memory for the coming generations.

Memories are not static; they are not only documented, stored, safeguarded, and later to be extracted, but they weigh like a phantasm on the consciousness of the living. Yesterday, the Shepherd was frightened by the dystopian vision: a society and nature in decay. Through memory, cultivated and enlightened in the crucible of struggle, the forecast of doom is poised to change. Storytelling will itself be an act of future creation.

Notes

- Nadir Bouhmouch and Kristian Davis Bailey, “A Moroccan Village’s Long Fight for Water Rights,” Al Jazeera, December 13, 2015, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2015/12/13/a-moroccan-villages-long-fight-for-water-rights.

- Zakia Salime, “Protest Camp as Counter-Archive at a Moroccan Silver Mine,” Middle East Research and Information Project, no. 291 (Summer 2019), https://merip.org/2019/09/protest-camp-as-counter-archive-at-a-moroccan-silver-mine/.

- Nadir Bouhmouch, “Amussu: Experiment for a Cinema from Below,” OpenDemocracy, April 1, 2019, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/amussu-experiment-cinema-below/.

- Ali Essafi, “A Brief History of Documentary Film in Morocco,” in Documentary Filmmaking in the Middle East and North Africa, ed. Viola Shafik (Cairo: American University of Cairo Press, 2022), 115–132.

- Fayrouz Yousfi, “COP22 in Morocco: Between Greenwashing and Environmental Injustice,” Middle East Eye, November 16, 2016, https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/cop22-morocco-between-greenwashing-and-environmental-injustice.

- Hamza Hamouchene, Extractivism and Resistance in North Africa (Amsterdam: Transnational Institute, 2019), https://www.tni.org/files/publication-downloads/web_maghreb_en_21-11-19.pdf.