Geographies of Care

By Caleb Simone

Volume 25, no. 3, Cooperation: Theory and Practice for the Commons

Lee este artículo en español aquí.

What does it mean to “fight” AIDS? For ACT UP, one of the most prolific activist groups in the United States during the early years of the pandemic, the fight was contingent on developing effective AIDS treatments and getting “drugs into bodies.”1 The pressure they put on the Federal Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) effected stunning changes to drug trial processes, and their persistent displays of public activism demanded national conversations about both “gayness” and HIV/AIDS. ACT UP’s impact was unprecedented during the late eighties and early nineties when dominant narratives portrayed AIDS as a “gay disease” and therefore a phenomenon to ignore. In part because of their high-profile activity, much of the academic discourse on AIDS-related activism and community support has focused on ACT UP.2 However, the same structures of oppression—namely, racism, classism, and biopolitics—that precipitated ACT UP’s work were perpetuated inside of the organization. Recognition of these perpetuations demands an interrogation of ACT UP’s academic and historical command.

In recent years, academics have paid increasing attention to ACT UP’s complicated legacy.3 ACT UP’s focus on “drugs into bodies” via federal reform often did not account for the differing socio-political realities impacting people with AIDS (PWAs) throughout the United States. For example, access to treatment and representation in federally funded drug trials was near impossible for a significant number of PWAs who were not white, male, and financially stable.4 While ACT UP spawned several impressive research groups to reclaim the power of treatment, people with cervixes, people of color, trans and gender-expansive people, poor people, and intravenous substance use disorder patients (ISUDPs) still found themselves underrepresented. Further, many of the scientific findings collected from the research groups were ultimately utilized by drug companies and the federal government. This outcome effectively transferred the power of treatment away from PWAs and their allied communities to the state.

This essay seeks to displace ACT UP as the center of grassroots organizing, so that a broader geography of AIDS-related care can emerge. Within this broader geography are examples of radical, community-driven responses to the AIDS crisis rooted in seizing scientific information, transforming it into community-specific knowledge, and developing mutual aid strategies to effectively disseminate that knowledge, therefore retaining the power of treatment and care.

A Critique of ACT UP

In the late eighties, ACT UP/New York collaborated with Needle Exchange Program (NEP) activist Jon-Stuen Parker to address the spread of HIV amongst ISUDPs. The coalition established NEPs throughout New York City to freely distribute clean needles.5 Due in large part to ACT UP’s alliances with other public health organizations and advocates, NEPs slowly gained institutional support and have since greatly increased in number.6 The effects of this development on PWA communities, however, is contentious.

Studies unequivocally show that access to clean needles reduces injection-related infections and overdoses.7 While NEP activists used the knowledge that clean needles save lives years before the CDC began conducting its own reviews in the mid-nineties, reported findings were instrumental in understanding the scope of NEPs’ benefits.8 However, the circumstances around such access animated existing structures of violence. ACT UP’s NEPs in the early nineties were based primarily in poor, working-class, Latinx and/or Black communities, where rates of drug-related HIV infections were soaring. The late eighties to mid-nineties represented a particularly devastating moment in the “War on Drugs.” The hyper-surveillance of poor minority communities by law enforcement led to some of the greatest recorded racial disparities in substance use-related arrests—tactics that persist decades later.9 ACT UP’s explicit defiance of laws criminalizing informal needle distribution and possession attracted additional police attention to communities already experiencing heightened police intervention. Some ACT UP members credit their NEP-related arrests and subsequent trials as pivotal in the eventual bureaucratic legitimization of NEPs. However, the institutional cooptation of NEPs placed them, and consequently their patrons, under state-mandated regulation and surveillance.

Despite the efficacy of NEPs, it is undeniable that what began as a grassroots harm reduction project turned into an institutional mechanism concerned with biopolitics.

HIV+ ISUDPs were, and are often still, blamed for contracting HIV. Imagining HIV as a consequence of intravenous substance use renders ISUDPs deserving of their diagnosis and contributes to the judgment that they are inherently “risky bodies.”10 This judgment turns ISUDPs into biopolitical subjects whose health warrants state intervention. Such imagining also disregards how the moralization and criminalization of substance use create the conditions—such as needle reuse and not seeking treatment for fear of arrest—that facilitate HIV contraction. This narrative further penalizes ISUDPs who are poor and Black or Brown, and therefore already at high risk for arrest and incarceration. Therefore, institutional involvement in NEPs can be read as a nefarious display of government regulation. On the other hand the rejection of NEPs by those with political authority has “been construed in some advocacy circles as acts akin to sanctioned massacres.”11 Despite the efficacy of NEPs, it is undeniable that what began as a grassroots harm reduction project turned into an institutional mechanism concerned with biopolitics.

Model for the Future: Mutual Aid?

How might communities invested in harm reduction avoid the institutional trappings of surveillance and biopolitics while taking advantage of valuable scientific information? Intentional efforts to operate independent of those trappings do exist, illustrating the manifold ways science can inform collective action.

Mutual aid is an alternative framework to state-surveilled activism. Defined by trans activist and lawyer Dean Spade, “Mutual aid is a collective coordination to meet each other’s needs, usually from an awareness that the systems we have in place are not going to meet them.”12 Communities exert the power of attending to their own care through harm reduction—an anti-carceral approach to community support which recognizes that “illegal” behaviors are responses to structural oppression, and carceral punishments for such behaviors only exacerbate the oppressive conditions which animate them. This approach is especially significant within marginalized communities that rarely benefit from federal programs and/or wish to avoid the surveillance and carceral threats inherently tied to the conditional care offered by federal and state initiatives.

Three organizations established in the mid- to late eighties approached AIDS activism from a perspective of mutual aid: Blacks Educating Blacks About Sexual Health Issues (BEBASHI), Vida/SIDA, translated to Life/AIDS, and Critical Path AIDS Project Newsletter (CPAPN).

BEBASHI: Philadelphia

Co-created by activist and medical provider Rashidah Abdul-Khabeer in 1985, BEBASHI was borne out of the sentiment that lack of information was the biggest threat to Black communities during the AIDS crisis.13 Rather than viewing disease ahistorically as an individual experience isolated from socio-political context, Abdul-Khabeer contextualized the AIDS crisis within a broader pattern of Black communities experiencing health crises due to state and federal neglect.14 For example, at the institutional level, Black and white gay men, and men who have sex with men (MSM), experienced grave restrictions in accessing medical care and visiting hospitalized lovers well into the nineties. At the local level, Philadelphia’s Black gay men and MSM received neither care nor support from the politically active segments of Philadelphia’s white gay community.15 Abdul-Khabeer observed how the compounded isolation of these communities limited access to critical scientific and medical information, consequently contributing to the spread of HIV in Black communities.

The difference in socio-sexual geographies inhabited by white and Black men impacted the types of information and care they received. Bathhouses were a locus for information activism. They were utilized as pseudo safe-sex classrooms across the country, featuring educational HIV/AIDS posters, free condoms, and lists of informational resources.16 However, they were most frequented by white cis men. Meanwhile, white gay bars and publications were the primary recipients of AIDS information activism. Consequently, Black Philadelphians were systematically excluded from broader resource-sharing efforts and therefore at higher risk for inadvertently contracting and spreading HIV. BEBASHI accounted for the spatial element of resource availability by distributing “survival packets” with “literature about AIDS, condoms, and bleach” (to sterilize needles) in cruising spots and bars frequented by Black men.17 The organization also threw “home parties,” during which prevention educators would visit the homes of Black community members to talk about safe sex and HIV/AIDS.18

BEBASHI designed its information activism around the lives of Philadelphia’s Black community members by meeting them in their own spaces with resources curated to their needs. This targeted outreach took the onus off of Black Philadelphians to appeal to white-focused institutions for resources. Due to the systematic neglect of Black Philadelphians and the spaces they inhabited, historian J.T. Roane refers to the community BEBASHI served as “those inhabiting the edge of social-spatial existence.”19 By focusing on that community without requiring their departure from that edge via individual behavior or spatial change, BEBASHI shifted the geography of AIDS-related care in Philadelphia. BEBASHI also shifted the geography and dimensions of scientific knowledge by bringing information about safe sex and HIV/AIDS to that social edge in localized formats. These shifts liberated community power from conditional frameworks of care and established spheres of mutual aid in their place.

Today, BEBASHI continues to empower community members through HIV/AIDS services, accessible and inclusive healthcare, social services, and prevention education. At the time of its creation and halfway across the country, a similar organization was translating crucial scientific information into accessible knowledge for another group of marginalized community members.

Vida/SIDA: Chicago

Vida/SIDA is an offshoot of the Puerto Rican Community Center based in Chicago’s West Town and Humboldt Park neighborhoods. Established in 1988 as a free alternative health clinic for PWAs, Vida/SIDA was created in direct response to the city’s inaction addressing the spread of HIV/AIDS in the Puerto Rican community.20 The health clinic acted as an anchor for community engagement and empowerment by providing a physical space to translate scientific information into community knowledge.21 For Vida/SIDA, this translation meant creating “culturally-competent HIV/AIDS risk-education and outreach” programs.22

Vida/SIDA incorporated harm reduction into their programs by focusing on communal realities rather than individual behaviors. This perspective is reflected in their decision—as opposed to the strategy widely adopted by Chicago’s Health Department—to educate and provide care for all members of their community rather than just gay men. By incorporating the experiences of women, ISUDPs, MSM, and gang members into the objectives of their organization, Vida/SIDA aimed to bridge the social classifications that exacerbated vulnerability to HIV exposure and infection.

Similar to BEBASHI’s focus on racialized spaces as resource limiters, Vida/SIDA recognized cultural and linguistic differences as barriers to resources. They responded to the lack of information precipitated by these differences by creating their own informational resources. From bilingual flyers for World AIDS Day to original theater produced entirely by members of Chicago’s Puerto Rican community, Vida/SIDA relayed messages about HIV/AIDS designed to meet their community’s needs and realities.

Establishing a collective history is a critical mutual aid practice; it encourages solidarity and communal resource sharing rather than reliance on institutional support.

Adjacent to their community-wide projects, Vida/SIDA built several programs to address the needs and experiences of distinctive groups within their community. For example, they created Nosotros Mismos (We Ourselves) in response to the prevalence of HIV/STIs among Puerto Rican gang members. Vida/SIDA acknowledged the significance of gang members in their community and recognized their potential as prevention education ambassadors. They promoted peer-to-peer knowledge transfers by providing gang members with the necessary scientific information and leadership tools to facilitate meaningful prevention conversations throughout the community.

Vida/SIDA also recognized the particular spaces women occupied in the AIDS crisis and the unique challenges they faced. For example, within the first decade of the crisis, cervical cancer was not included among the opportunistic infections that warranted an official AIDS diagnosis. Consequently, a substantial number of people at risk of cervical cancer were disqualified from receiving medical and financial support. In response to these inequities of care, Vida/SIDA created Las Cimarronas.23 Another peer-based group, Las Cimarronas developed prevention education and harm reduction programs for young Puerto Rican and Latina women, specifically those who were parenting, pregnant, and/or not in school. In doing so, Vida/SIDA fostered community amongst another population typically absent in state initiatives and provided them tools to share knowledge.

Vida/SIDA embodied the same rejection of ahistoricism advanced by Abdul-Khabeer; the name “Las Cimarronas” originates from women in Caribbean societies who resisted enslavement and practiced holistic methods of medical care. Establishing a collective history is a critical mutual aid practice; it encourages solidarity and communal resource sharing rather than reliance on institutional support. Similar to the mutual aid tactics employed by BEBASHI, Vida/SIDA made conscious efforts to address the needs of community members without using conditional frameworks of care that required behavioral or geographic changes. This approach facilitated community empowerment by situating individual circumstances into a collective socio-economic structure and history. Finally, both Vida/SIDA and BEBASHI transformed and disseminated information within their communities, thus broadening the geographies of AIDS-related care in large part through peer-to-peer transfers of knowledge. Commensurate impacts can be seen through the work of the Critical Path Project, which represents the final mutual aid-based AIDS activism organization explored in this essay.

The Critical Path Project: Tri-State Area

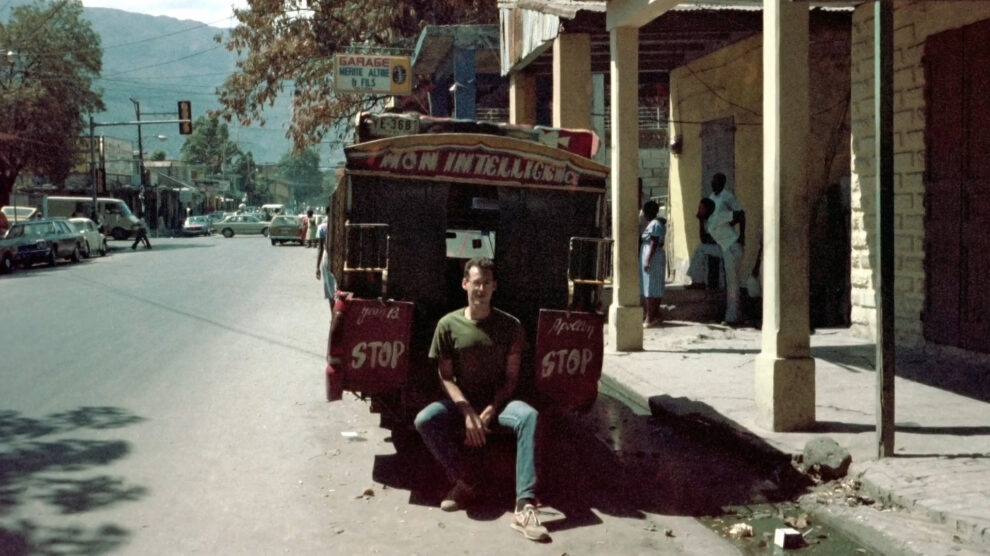

The Critical Path Project was created in 1989 by an esteemed activist, Kiyoshi Kuromiya. Critical Path began as a 24/7 support hotline for PWAs.24 To disseminate critical information to PWAs, Kuromiya added a Bulletin Board System (BBS) to the hotline. Popular in the early nineties and now almost unknown, BBSs were an early type of computer software that connected users to online resources via modem. Kuromiya would upload scientific research, often as a colloquial interpretation, along with local mutual aid resources onto the BBS and connect callers via telephone or modem. When Critical Path adopted its own exclusive BBS in 1991, its users were granted messaging, uploading, and sharing capabilities. While the introduction of the BBS expanded Critical Path’s technical capabilities, connection required technological access and literacy. To counter those elements of inaccessibility, Kuromiya created the Critical Path AIDS Project Newsletter (CPAPN).

The CPAPN was the printed version of the information available via BBS, freely distributed amongst PWAs and incarcerated individuals. One remarkable element of this communal resource was the incorporation of news on current and upcoming clinical drug trials.25 In the late eighties and early nineties, drug studies for HIV/AIDS were comprised primarily of cis white gay men due to their medical privileges and status as “pure” test subjects.26 The dissemination of drug trial information provided populations without regular medical care access to potentially life-saving drugs. The diversification of drug trial participants also broadened the scope of medical backgrounds included in the formulation of effective HIV/AIDS drugs. Shared access to this information encouraged community-building among PWAs across multiple geographies and transformed the CPAPN into a composite of many voices, experiences, and messages.

Approaches to fighting AIDS must be grounded in how it materializes in different geographies and on the understanding that no single group can traverse it alone.

The CPAPN routinely incorporated information relevant to incarcerated PWAs and letters written by them. The writers often included their prison addresses and a message encouraging readers to reach out, facilitating community formation across carceral boundaries. These letters provided intimate insight into the challenges that prisoners with HIV/AIDS faced within the carceral cycle. Mike Ruggieri, a frequent incarcerated contributor, provided updates on the dismal health services provided to HIV+ prisoners in Pennsylvania, including the complete lack of prevention and care information disseminated throughout prisons. The CPAPN was distributed freely to prisoners, thus helping to fill a critical gap in AIDS-related knowledge amongst an intentionally isolated population. Furthermore, incorporating the voices of incarcerated PWAs fostered solidarity across material and circumstantial differences. By facilitating that solidarity, the CPAPN prompted its readers and contributors to include carceral contexts in their understanding of relevant information, effectively broadening their conceptions of AIDS-related issues and communities.

Approaches to fighting AIDS must be grounded in how it materializes in different geographies and on the understanding that no single group can traverse it alone. The fight also requires an understanding that science is not a monolith. All communities interested in mutual aid can benefit from the translation of scientific information into community knowledge. Translation is not a monolith either; communities have been and always will be experts in their own care. Therefore, the scientific information that is relevant and the shape of its translation will differ depending on the need, context, and history of each community. Case studies like BEBASHI, Vida/SIDA, and the CPAPN provide useful translation frameworks. Perhaps most importantly, they illustrate how scientific, historical, and activist work are more closely linked than their separate praxes suggest. The fluency of interdisciplinary work must be our first step towards the collective seizure of science for mutual aid purposes.

This article is part of our Winter 2021 issue: Cooperation. We will gradually post articles online in the coming months. Subscribe or purchase this issue to get full access now.

Notes

- David France, How to Survive a Plague: The Story of How Activists and Scientists Tamed AIDS (New York: Vintage Books, 2016).

- Priscilla Wald, Contagious (Duke University Press, 2008), 219. Although much work has been done to dismantle the discriminatory association between gayness and HIV/AIDS, misinformation and lack of comprehensive sex education curricula allow this stereotype to persist in American AIDS mythologies. Look to Cindy Patton’s Fatal Advice for in-depth discussion on the early relationship between HIV/AIDS and sex education.

- Deborah B. Gould, “ACT UP, Racism, and the Question of How To Use History,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 98, no. 1 (February 2012): 54–62.

- Steve Epstein, Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 253–59.

- Christina B. Hanhardt, “Dead Addicts Don’t Recover: ACT UP’s Needle Exchange and the Subjects of Queer Activist History,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 24, no. 4, Duke University Press (2018): 432–33.

- Don C. Des Jarlais, Courtney McKnight, and Judith Milliken, “Public Funding of US Syringe Exchange Programs,” Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 81, no. 1 (March, 2004): 118–121;

- Katherine McLean, “The Biopolitics of Needle Exchange in the United States,” Critical Public Health 21, no. 1 (March, 2011).

- Richard Weinmeyer, “Needle Exchange Programs’ Status in US Politics,” AMA Journal of Ethics 18, no. 3 (March 1, 2016): 252–57, https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.3.hlaw1-1603; D. C. Des Jarlais, “Research, Politics, and Needle Exchange,” American Journal of Public Health 90, no. 9 (September 2000): 1392–94.

- Jamie Fellner, “Race, Drugs, and Law Enforcement in the United States,” Stanford Law & Policy Review 20, no. 2 (2009): 271–72; Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2012); Ojmarrh Mitchell and Michael S. Caudy, “Examining Racial Disparities in Drug Arrests,” Justice Quarterly 32, no. 2 (2015): 288–313.

- Cindy Patton, Inventing AIDS (New York: Routledge, 1990), 65–6.

- McLean, “The Biopolitics of Needle Exchange in the United States.”

- Dean Spade, Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (And the Next) (New York: Verso, 2020): 9, 13.

- Lini Kadaba, “The Black Warning,” Philadelphia Inquirer, originally published July 8, 1990, Rashidah Abdul-Khabeer Personal Collection, African American AIDS History Project, http://afamaidshist.fiu.edu/omeka-s/s/african-american-aids-history-project/item/2569.

- J.T. Roane, “Black Harm Reduction Politics in the Early Philadelphia Epidemic,” Souls 21, no. 2–3 (2019): 148, http://doi.org/10.1080/10999949.2019.1697131.

- Dan Royles, “Oral History Interview with Rashidah Abdul-Khabeer, April 11, 2012” African American AIDS Oral History Project, http://afamaidshist.fiu.edu/ohmsview/viewer.php?cachefile=Interview27628.xml.

- William J. Woods and Diane Binson, “Public Health Policy and Gay Bathhouses,” in Gay Bathhouses and Public Health Policy, ed. William J. Woods and Diane Binson (New York: Harrington Press, 2003), 1–21.

- Cruising is a socio-sexual practice historically associated with gay men. Participants “cruise” spaces like parks or public bathrooms to find another participant—typically a stranger—with whom to engage in sexual activities..

- Dan Royles, To Make the Wounded Whole: The African American Struggle Against HIV/AIDS (University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 35; Gay Community News, “Black Group Gets AIDS Education Money,” originally published February 14-20, 1988, Northeastern University Libraries, https://archive.org/details/gaycommunitynews1530gayc/page/2/mode/2up?q=bebashi.

- Roane, “Black Harm Reduction,” 147.

- Roberto Sanabria, “Vida/SIDA: A Grassroots Response to AIDS in Chicago’s Puerto Rican Community,” Convergence 17, no. 4 (2004): 37.

- Rachel Rinaldo, “Space of Resistance: The Puerto Rican Cultural Center and Humboldt Park,” Cultural Critique, no. 50 (Winter, 2002): 135–174.

- Puerto Rican Cultural Center collection, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago.

- It should be noted that Las Cimarronas is a self-described group for women. Vida/SIDA currently provides services that cater to the needs of LGBTQ individuals, but it is unclear whether trans women utilized their services when Las Cimaronnas was developed. And while Las Cimarronas was created in response to inequities in women’s care such as the disregard for cervical cancer as an AIDS-related OI, it was not created to address that issue exclusively and cannot be considered a comprehensive response to all PWAs who were at risk of developing cervical cancer.

- Cait McKinney, “Printing the network: AIDS activism and online access in the 1980s,” Continuum: Journal of Media & Culture Studies 32, no. 1 (2018): 9.

- “AIDS Info BBS: AIDS Periodicals,” 29, Queer Digital History Project, accessed December 15, 2020, http://www.queerdigital.com/items/show/96.

- Steve Epstein, Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 208–264.