September 26, 2022

Spread This Like Wildfire!

By Jedidiah Carlson

There has been no shortage of controversies surrounding citation practices in research, and in May 2022, the scientific community became embroiled in one of the more heated citation-related scandals in recent memory. After an avowed white supremacist massacred ten people at a grocery store in Buffalo, New York, it came to light that the shooter had released a 180-page screed referencing dozens of scientific studies as evidence for “race realism” and the supposed intellectual and cultural inferiority of the Black community he targeted. This sparked a deluge of commentary from scientists, who roundly excoriated the shooter’s flawed interpretations of the research he cited. Major academic societies and consortia released statements underlining their commitment to liberal values, including how modern genetics research is fundamentally incompatible with racist interpretations. Above all, scientists grappled with the question of what should be done to address their unwitting role in perpetuating racist violence. The prevailing sentiment—that the scientific community must “recognize and address the racist use of genetic research…[and] take an active role in fighting white supremacy”1—was repeatedly presented as a destination at the end of an unmapped road, devoid of any guidance and actionable building blocks for achieving that goal.

How should scientists recognize, address, and actively fight against racist co-optation of research? It is a provocative question that festers beyond the edge of most scientists’ comfort zones. For many, sternly worded repudiations were a sufficient and self-enclosed answer, conflating acknowledgment and communication about the weaponization of science with meaningful action towards the resolution thereof.2 Others cynically argued that the far-right’s co-optation of science has always been a sociopolitical problem that we are powerless to address (or, as some might even claim, obligated to ignore).3 A few progressive voices ventured to suggest ambitious reforms targeting the funding, conduct, and communication of socially sensitive research. These suggestions ranged from promoting a nuanced, diversity-embracing genetics curriculum in schools to more aggressively deplatforming racist pseudoscientists and discrediting their claims.4 But even these relatively mild insinuations that science should be held to a higher technical and ethical standard were deplored as a slippery slope to censorship and infringement on academic freedoms.5

Absent from this discourse was a deeper discussion of how science became a weapon of far-right ideology. Addressing this question paints a fuller picture of the role that contemporary science plays in the far-right (mis)information ecosystem—not only how research is willfully misunderstood by these communities, but how mainstream science becomes grist for the mill of far-right metapolitics, conspiracy theories, and recruitment and propaganda materials. More importantly, this question leads to a more pointed perspective about the scientific community’s role as stewards of the knowledge it generates. This essay traces the lineage of science as an ideological weapon of the postmodern far-right,6 deconstructs examples of such propaganda as they appeared in the Buffalo shooter’s screed, and explores the social consequences of the scientific community’s successes and failures in mobilizing against that propaganda. I conclude with a discussion of specific actions we might take to build a robust and sustainable mechanism for countering weaponized science.

When Science Becomes Weaponized: The Case of the National Front

The Buffalo shooter’s scientific bibliography has clear echoes to a similar citation scandal that arose in the late 1970s and early 1980s. During this era, the National Front (NF), a neofascist political party in the UK that had been steadily growing throughout the 1970s, distributed a series of pamphlets with articles referencing mainstream academic research. Their goal was to justify the organization’s platform of ethnic nationalism, white supremacism, and eugenics using contemporary science. The first wave of NF propaganda proclaimed, “scientists say that races are born different in all sorts of ways, especially in intelligence. This is because we inherit our abilities genetically.” Here, the NF cited the work of Hans Eysenck and Arthur Jensen, two of the most vocal proponents of the hereditarian theory that genetics could explain IQ differences between racial groups. Steven Rose, a champion of radical science and coauthor of Not in Our Genes with Richard Lewontin and Leon Kamin, lambasted Eysenck and Jensen in a 1978 letter to the editor of Nature, calling upon them to “publicly and unequivocally dissociate themselves from the National Front and its use of their names in its propaganda.”7 Eysenck and Jensen both complied with Rose’s request, albeit without a hint of apology for the societal harm their research precipitated. Eysenck asserted that he was “absolutely opposed to any form of racism” and claimed that “No-one familiar with Professor Jensen’s or my own writings could possibly misinterpret our arguments about the mean differences between various racial and other groups with respect to intelligence as implying the kind of policies advocated by the National Front.”8 Jensen echoed this self-absolving and patently false sentiment but also took the opportunity to lash out against his leftist critics for being, as he believed, as guilty as the far right in their desire “to promote and to gain public acceptance of a particular dogmatic belief about the nature of racial differences.”9

A year later, the NF reprised its propaganda strategy with an article in its flagship publication, Spearhead, titled “Sociobiology: The Instinct in Our Genes,” which glowingly referenced E.O. Wilson’s recently published book on the topic (as well as the writings of other sociobiologists) to claim that racism and discrimination were immutable and desirable biological characteristics.10 By this point, sociobiology had attracted a panoply of critics who saw the discipline as little more than a façade for obscene biological determinism that danced to the tune of right-wing ideology. The NF’s embrace of sociobiology vindicated those speculations, and critics quickly rallied to hold sociobiologists accountable for passively providing an aegis of scientific legitimacy to a violent fascist organization. That autumn, the Boston chapter of Science for the People organized a forum entitled “Biology as a Social Weapon” to discuss further the inherent political basis of sociobiology and how to respond to its newfound cultural niche as a tool of neofascism.11

The following year, in 1980, two more articles appeared in successive editions of another NF-run journal, New Nation, this time citing sociobiological works by John Maynard Smith and Richard Dawkins. Steven Rose again turned to the letters section of Nature to call upon Dawkins and Maynard Smith to “clearly dissociate themselves from the use of their names in support of this neo-Nazi balderdash.”12 Though the two quickly responded with letters of their own in Nature, their rhetoric, like that of Eysenck and Jensen, was transparently dismissive of the NF as a threat to both the scientific community and society at large. Maynard Smith curtly asserted that the scientific evidence did not support the NF’s interpretation:

…a right-wing journal, New Nation, has quoted me, together with other evolutionary biologists, in support of their view that our genetic constitution makes it impossible for us to live in a racially integrated society. I welcome the opportunity to say that there is nothing in modern evolutionary biology which leads to this conclusion.13

Dawkins expressed his “annoyance” that his theory of kin selection had been “dragged down to the ephemeral level of human politics, and parochial British politics at that.”14 Like Jensen before him, Dawkins’s retort to Rose careened away from reckoning with the practical implications of his science being used to support the National Front’s fascist uprising and anti-immigrant violence.15 Dawkins instead directed much of his outrage towards Rose and other critics for what he perceived as a Marxist agenda to portray his theory as intrinsically aligned with right-wing ideology.

Retrospective accounts of this controversy tend to unilaterally focus on scientists as the only players of interest, painting the NF as little more than a confounding pawn in the intellectual chess game between sociobiologists and their critics. In reality, the NF had not only stumbled into a successful formula for repackaging scientific literature into racist propaganda, but, in doing so, they repeatedly exposed the scientific community’s general reluctance to acknowledge and grapple with the negative social impacts of their work. Although the NF splintered and atrophied throughout the 1980s, its various offshoots continued to refine this propaganda strategy throughout the 1990s and well into the twenty-first century. Most notable is the British National Party (BNP), a splinter of the NF founded by its former leader, John Tyndall, that eventually far surpassed the NF in electoral popularity. Initially, under Tyndall’s leadership, BNP redoubled its efforts to promote ethnic nationalism via Jensenism and sociobiology. Later, during Nick Griffin’s tenure, BNP shifted its official platform toward a subtler scientific racism that leaned heavily on population genetic and anthropological research of the pre-modern peoples of the British Isles to promote a new “scientifically founded” flavor of ethnic nativism.16 During this time, the BNP achieved its highest electoral turnout, earning over half a million votes in 2010.

Ever since NF’s first foray into scientific propaganda, this cycle of right-wing co-optation of science followed by a toothless response from the scientific community has plodded forward. There is a brief flicker of collective outrage among scientists and even the rare suggestion that we should reform the academic systems that turn a blind eye to the dangers of weaponized science, but the accelerated pace of similar episodes in recent years (e.g., Donald Trump’s 2016 and 2020 campaign speeches promoting the concept of “good genes,” the scientific racism espoused by attendees of the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville in 2017, and a 2019 documentary in which Nobel laureate James Watson doubled down on his past racist and sexist statements) testifies to the failures of such reforms to ever gain traction and crystallize.

The Meme-ification of Scientific Research

The Buffalo shooter’s monograph (along with the more than 600-page “diary” he logged on Discord, a chat app popular with the far-right) is peppered with “scientific” arguments that have been continually reengineered and repurposed over the past fifty years by the far-right. Though the shooter’s writing will go down in history as a disturbing monument to his violence, it serves as a remarkably useful resource for scientists to unpack the etiology and semiotics of weaponized science in the twenty-first century, how it evolves, and how we might respond to it more effectively.

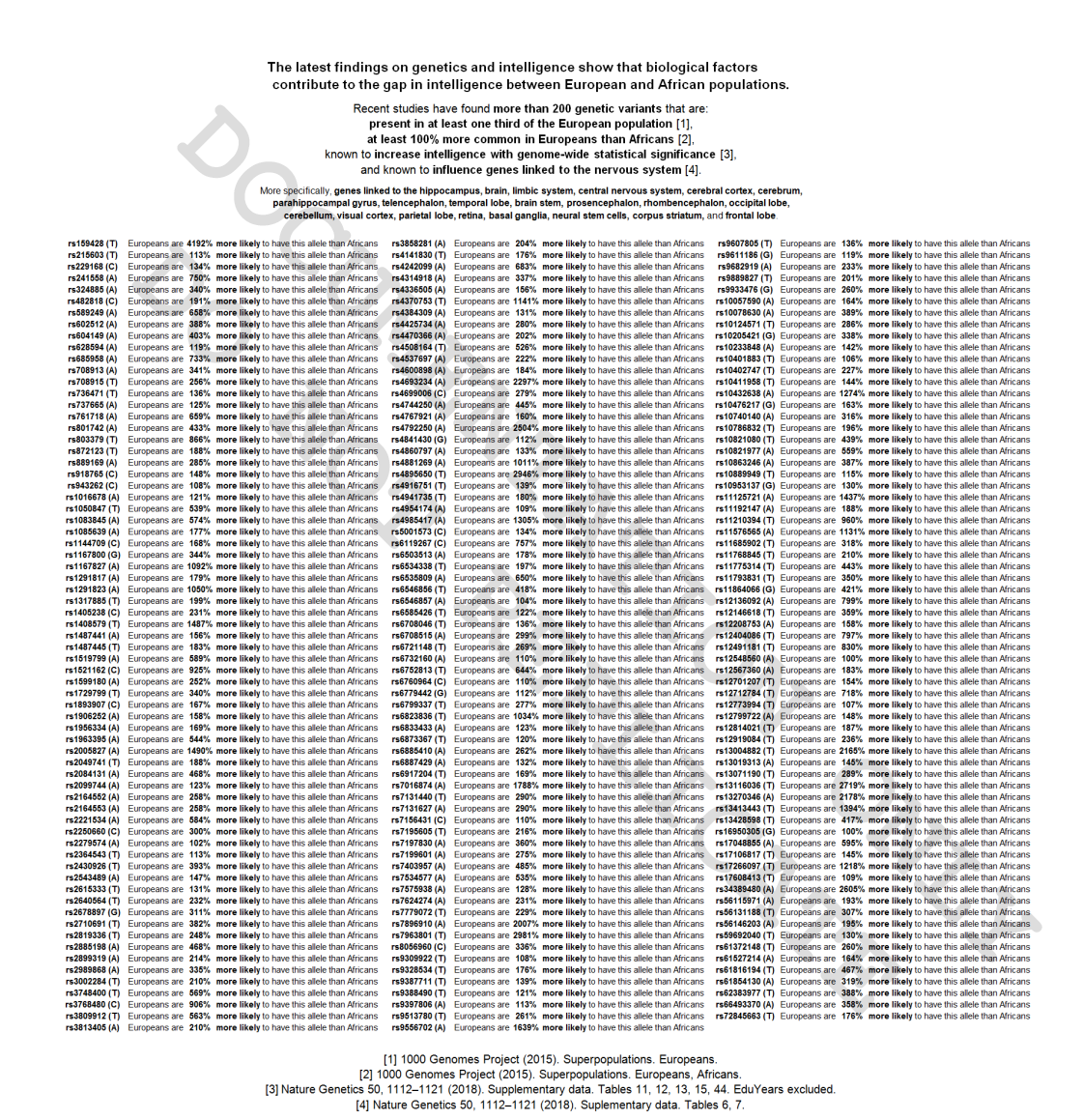

Much of the scientific community’s outrage in the aftermath of Buffalo centered around the shooter’s citation of a paper colloquially known as the “EA3” study (Lee et al., published in 2018 in Nature Genetics).17 This study, carried out in over 1.1 million individuals of European descent, identified hundreds of genetic variants associated with “educational attainment” (often abbreviated to EA)—i.e., the number of years of school completed, often taken to be an “easy-to-measure” proxy for intelligence.18 The shooter’s reference to the EA3 study came in the form of a screenshot of a plain-looking document (figure 1) proclaiming, “The latest findings on genetics and intelligence show that biological factors contribute to the gap in intelligence between European and African populations.” Beneath this image, the shooter weighed in with his own interpretation, punctuating his earlier claims that “whites and Blacks are separated by tens of thousands of years of evolution, and our genetic material is obviously very different.”

Many variations of this table can be found throughout the internet, but the earliest version can be traced back to a thread on 4chan (an anonymous and largely unmoderated online forum) timestamped to September 15, 2018, barely six weeks after Lee et al. was published online (on July 31, 2018). The original post that initiated this thread (figure 2) is a perfect example of what sociologist Aaron Panofsky calls “citizen scientific racism”: an individual, having come across the EA3 study, collected the top EA-associated variants from a supplementary table of the paper, annotated these variants with the allele frequencies in European and African populations using publicly available data from the 1000 Genomes Project, and curated a set of EA-associated variants with the greatest differences in population frequency to argue that Europeans are genetically predisposed to higher intelligence.19

The responses to this thread rapidly crystallized into a simple propaganda strategy: turn these “findings” into a standalone unit of easily-digestible visual information—or a meme, for lack of a better term—and let it organically spread across other online spaces. Shortly thereafter, another user took these suggestions to task and independently reproduced the original post’s analysis, presenting the results in a table similar to that shown above. Within hours, this image began to circulate in other 4chan threads and mutate into alternate versions, often accompanied by zealous calls for diffusing these memes throughout the internet. “SPREAD THESE IMAGES LIKE WILDFIRE,” encouraged one user. “This is the new IOTBW” said another, referring to the racist slogan, “It’s OK to be white.” The meme was even passed on to a cabal of popular alt-right bloggers and Youtubers who “have several PhDs and can give you a hand…plus they’re fantastic propagandists.” This collective enthusiasm for propagandizing the EA3 study appears to have been wildly successful. Altogether, variations of this meme have been posted over 5,100 times on 4chan and regularly appear on more mainstream social media platforms like Reddit, Twitter, and Quora. Contrary to the scientific community’s prevailing narrative that the shooter was an isolated extremist who happened to stumble upon the study,20 these data demonstrate that the EA3 study has been a significant force in empowering far-right extremists for years, virtually since the day it was first published.

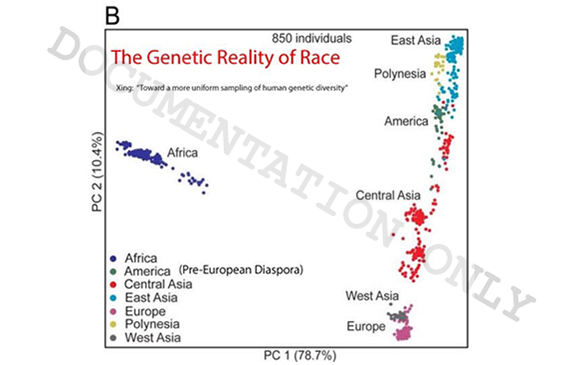

Other elements of the shooter’s online presence suggest that co-opted science was deeply embedded in his racist ideology. Allegedly, the banner image on the shooter’s Twitch (a social media platform) profile from which he live-streamed his atrocity was a modified version of a graph from a population genetics paper published in the journal Genomics (figure 3).21 As I have written about previously, this figure is one of the most popular “scientific” memes that circulate among far-right communities.22

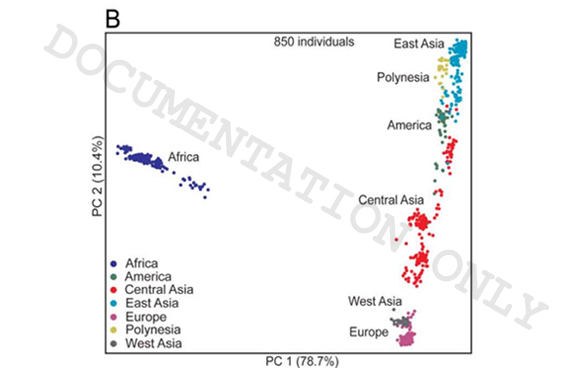

So where did this meme-ified scientific figure originate, and what made it so appealing to the shooter? The Xing et al. study was among a flurry of analyses in the late aughts that attempted to summarize the extent of genetic diversity in the human species, coming on the heels of the Human Genome Project and newly available sequencing and genotyping technologies. Bibliometrically, it is not what we would consider a “landmark” paper in the field, having been cited fewer than one hundred times in the last twelve years. The original figure from Xing et al.’s paper, commonly known as a PCA (Principal Components Analysis) plot, is shown in figure 4 in its unmodified form.

As applied to population genetics, the proximity between any pair of points in a PCA plot is generally interpreted as a measure of genetic relatedness: points closer together are assumed to share a more recent common ancestor than points further apart. Because PCA is used to quantify and visually summarize patterns of genetic variation between individuals, it can be particularly effective for exploratory analysis and quality control in genomic studies. However, PCA can be extraordinarily sensitive to various meta-parameters (many of which are highly subjective) that influence how the data is visualized and interpreted. It has even been argued that these parameters can be manipulated to generate desired outcomes.23 Despite the popularity of PCA in the field, population geneticists broadly agree that such visualizations warrant cautious interpretation and can often lead to misconceptions about the global distribution of genetic variation.

With these technical caveats in mind, let us return to the version of the Xing et al. figure found on the shooter’s Twitch profile. Like a “spot the differences” book you might find in the lobby of a pediatric dentist, there are three fairly obvious distinctions between the modified and original figures. In the same way that the EA3 meme employs scientific jargon and bibliographic norms to appear dry and dispassionate, the annotations made to the Xing et al. figure follow the conventions of scientific communication to convey a sense of scientific authority. First is the addition of a visually and semantically bold red title, “The Genetic Reality of Race.” Scientists will often use such annotations when presenting figures in a talk. With only a few precious seconds to describe a complex visualization, it is convenient to simply state the gist of how it should be interpreted and verbally assure viewers that this interpretation is logically sound, circumventing the need to explain its nuances and caveats. In this case, however, the interpretation conveyed by the meme is directly at odds with that of the original paper. Beneath this title, Xing et al. is credited and the title of their actual paper is given in much smaller font. This serves to reconcile two seemingly disparate aspects of the propagandized figure: (a) the bibliographic reference lends it an air of scientific legitimacy, and (b) the tiny font downplays the authors’ own high-level titular summary of their research, almost making it subservient to the interloping caption. The third difference is found in the legend, where the green point representing the “America” population is supplemented with a parenthetical “(Pre-European Diaspora),” in an apparent attempt to clarify that this cluster does not represent the contemporary white populations in North and South America that descended from European colonizers and immigrants. Collectively, these modifications fully detach the figure from its context24—it is treated as a standalone unit of “scientific” information that forcefully asserts genetic evidence for “race realism.”

A cursory reverse image search reveals that the image has been posted repeatedly in the last twelve years on a range of mainstream platforms, as well as blogs dedicated to the topic of “human biodiversity” (widely considered to be a dog whistle for scientific racism, repackaged with liberal terminology), and the more extreme 4chan-offshoot image boards like 8kun, 16chan, and Neinchan. On 4chan alone, there are over one thousand posts in the last eight years that have included this image, and it is regularly featured in “red-pill dumps”—overwhelmingly large collections of multimedia that are regularly posted in these spaces, seemingly with the intent of radicalizing readers via (mis)information overload.

There are many, many other examples of scientific figures that have received similar treatment by the far-right. What’s curious about these “scientific” memes is that they are almost entirely invariant between platforms, and the versions that appear on the most extreme far-right enclaves are identical to those encountered on mainstream social media (e.g., Twitter and Reddit).25 If we naively conceptualize “online radicalization” as a descent from “gateway” platforms into more extreme online spaces, the fact that these “scientific” memes persist across that gradient is quite alarming.26 They effectively serve as emblems of pseudo-rational justification for increasingly violent and fanatical content on the periphery.

Reviving the Ghosts of Radical Science

The memes deployed by the Buffalo shooter have explicit origins as propaganda by a decentralized and amorphous far-right community, whose warped form of scientism is one of its few unifying features and the foundation on which numerous violent conspiracy theories are constructed.27 As we connect these threads of weaponized science to those of (neo-)fascist groups of decades past and consider how the scientific community might respond to its current manifestations,28 it behooves us to draw insight and inspiration from how scholars involved in radical science movements of the 1930s and 1970s fought against them.

Throughout Europe (and, to a lesser extent, the United States) in the 1930s, scientists were becoming increasingly cognizant of the interpenetration of scientific research and the sociopolitical structures in which science was embedded. The “Social Relations of Science” (SRS) movement (sometimes referred to as “the visible college”) in the United Kingdom was at the vanguard, spearheaded by prominent leftist scientists like J. D. Bernal, J. B. S. Haldane, Lancelot Hogben, Joseph Needham, and others.29 The SRS movement openly advocated for socialism as the only plausible societal structure in which science and technology could freely advance to serve the needs of the people.30 In pursuit of this vision (and mobilized by the threat of fascism sweeping through Europe), the SRS movement urged scientists to become politically and socially engaged. Bernal’s landmark book, The Social Function of Science (1939), elaborated on this perspective, arguing for the necessity of extracurricular social action under the looming shadow of the Second World War:

The great Nazi myth of race superiority and the [fascist] necessity for military struggle have to be given a scientific basis, and the whole of biology, psychology, and the social sciences need to be distorted for this purpose…It is easy for a scientist, in what is still a bourgeois democracy, to look with superior horror at what is happening to science under Fascism [in Germany and Italy]. But the fate of science in his own country is at the moment still hanging in the balance and it depends on factors quite outside the scope of science itself. Unless the scientist is aware of these factors and knows how to use his weight in influencing them, his position is simply that of the sheep awaiting his turn with the butcher.31

Bernal’s call was not for scientists to demurely participate in the existing order, but for organized defense—and, if necessary, rebellion—against political forces that threatened science as an engine for improving the human condition. Bernal himself was known for putting his words into practice: he founded the Association of Scientific Workers (one of the earliest attempts at forming a scientific trade union) and “For Intellectual Liberty,” a group of UK-based scientists and writers opposed to fascism. Bernal and Haldane were also a frequent presence in the anti-fascist bloc that fought in the streets against Oswald Mosley’s fascist uprising.32 For biologists, geneticists, and anthropologists in particular, these anti-fascist convictions often had a direct connection to their own scholarly research.

Well before the publication of Bernal’s book (and continuing throughout the Second World War), scientists across Europe had already become an important demographic within militant anti-fascist resistance groups. The most famous of such networks were the intelligentsia-heavy Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes and the Groupe du musée de l’Homme in France, which counted Nobel laureates Paul Langevin, Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie, and Jacques Monod33 among their ranks. Like Bernal and the leaders of the SRS movement in the United Kingdom, the scientists involved in the French Resistance were prolific organizers and embedded themselves in the vast network of groups fighting against the Nazi occupiers and their French sympathizers. In August 1944, these scientists played a particularly important role in the liberation of Paris: Monod helped coordinate the general strike that precipitated the erection of barricades throughout the city and mobilization of paramilitary resistance units, and Frédéric Joliot-Curie set up a production line for Molotov cocktails that resistance fighters successfully used to disable numerous Nazi tanks and vehicles.

Meanwhile, in the United States, anthropologist Franz Boas and his allies34 waged a relentless political battle against the scourge of weaponized science,35 particularly as it manifested in and around public schools. In 1939, the New York State Chamber of Commerce published a series of reports by eugenicist Harry H. Laughlin that advocated banning all non-white immigrants and slashing the budgets of public schools that primarily served first-generation immigrants. Boas, who had retired in 1936, staged an aggressive multi-front counterattack that involved not only publicly challenging Laughlin’s claims on scientific grounds, but also co-organizing rallies with teachers’ unions and school administrators, publishing a damning audit of the unscientific claims about race in school textbooks, producing anti-racist pamphlets and radio programs for public consumption, and directly working with teachers to revise outdated curricula pertaining to race.36

Synthesizing the lessons learned from past radical science movements provides us with a path forward: our collective response to weaponized science must be fiercely multimodal and operationally diverse, taking place in the pages of scientific journals, the digital streets of social media, and the physical spaces of our institutions and cities.

Altogether, the activist-scientists in the United States and the United Kingdom during this era embraced a multimodal approach to combating weaponized science that included political advocacy, labor organizing, metascientific research, street protests, and tireless science communication, education, and journalism. Importantly, these activities transcended the boundaries of scholarly disciplines and the chasm between scientists and the public. The parallel experience of activist-scientists in occupied France, where militancy had become the only option, was a conspicuous reminder of what was at stake if weaponized science was allowed to spread uncontested.

After the Second World War, however, the movement’s momentum rapidly deteriorated and its proponents were politically and intellectually marginalized.37 As the Cold War erupted and communism supplanted fascism as the primary political threat to the Capitalist Bloc, leftist philosophies of science were attacked as unscientific and immoral.38 Some of the ambitious goals of the radical science movement were realized, such as massive increases in federal funding for research and the establishment of an international agency (UNESCO) to advance education, science, and culture, but these successes were thoroughly commandeered in the service of capitalism. Although the UNESCO statements on race in the early 1950s were widely viewed by progressive scholars as a declaration of victory over scientific racism, these statements failed to meaningfully reshape public opinion about race (particularly in America),39 exposed the ongoing ideological rifts and racist sentiments still held by many scientists,40 and significantly contributed to late colonial and post-colonial intervention in the Global South, offering “a moral incentive for scientific elites to intervene in the ways of life of those deemed primitive.”41

These shortcomings of the UNESCO statements were violently reified in the 1960s, as the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement sparked a new reckoning in the scientific community over the role science played in developing literal and ideological weapons of oppression.42 In 1972, in response to the race science doctrines of Eysenck, Jensen, William Shockley, and Richard Herrnstein, a coalition of over 1,400 academics formed the International Committee Against Racism (InCAR). InCAR’s early public statements (most notably a full-page ad in the New York Times, titled, “A Resolution Against Racism”) included not only a scathing scientific repudiation of race science doctrines, but an explicit call to “organize and support activities to eliminate racist practices and ideas wherever they occur.”43 Writing for Science for the People in 1974, Phil Czachorowski, a member of InCAR, elaborated on how such actions had already begun to take shape in communities most vulnerable to scientific racism’s political and social consequences:

These battles in and around academia will be significant only when combined with attacks on many other fronts. Successful campaigns have been waged to abolish IQ testing in some schools, and in some cases courts have ruled that IQ tests are (racially) discriminatory. In some cases the courts have also ruled against using IQ tests for screening job applicants. But the battle must go far beyond the courts, to militant organizing of teachers and students and parents against IQ tests, to militant organizing of black and white workers against the racism on the job, to the militant organizing of all working people against the ideas and practices that keep them divided.44

The aforementioned NF episode vindicated these activist-scientists’ fears that Jensenism and sociobiology would inevitably leach into the groundwaters of neofascism—here was plain evidence that a far-right organization, explicitly modeled after Mussolini’s Blackshirts, had embraced mainstream science as a growth medium for their ideology. Exposing this symbiosis in a public forum and forcing those scientists to contend with the political implications of their work was an important and legitimate tactic, but this was only intended to be the beginning. Writing for Science for the People in 1978, Hillary and Steven Rose (who had initially sounded the alarm in his letter Nature about NF propaganda) shed the diplomatic air reserved for a scientific journal and called upon other radical scientists in the United States and the United Kingdom to take up a multimodal approach reminiscent of that employed by the 1930s’ generation of radical scientists, coupling the intellectual struggle against scientific racism with collaboration alongside teachers, students, community groups, labor unions, and front-line activists.45

In the United States, InCAR seemed especially well-poised to lead and sustain this movement: the group was initially formed as a nonsectarian coalition of anti-racist intellectuals and garnered broad support from scientists who otherwise may have been politically squeamish about aligning themselves with InCAR’s hard-line Maoist parent organization, the Progressive Labor Party (PLP). Over time, however, the PLP slowly began to refashion InCAR into an activist front for the party, which alienated many members and damaged InCAR’s reputation with labor unions and other allied organizations.46 Notably, PLP leadership looked down upon InCAR members’ efforts to scientifically discredit Jensen and other race scientists, believing that opposition should be “purely political” in nature.47 Consequently, InCAR’s opposition to Jensen and Wilson et al. took the form of outrageous polemic attacks and theatrical stunts, including a notorious incident in which members disrupted a lecture by Wilson and poured a bucket of water on his head, chanting “racist Wilson you can’t hide, we charge you with genocide!”

Incidents like this sidelined the vitally important battle to discredit the validity of sociobiology and Jensenism. Those who were targeted leveraged these incidents to legitimize their research programs, paint themselves as victims of “the intolerant left,” and accumulate further academic prestige and influence. Paradoxically, by centering sociobiologists and Jensenists as the sole targets of the radical science movement, InCAR and other activist-scientists failed to fully appreciate the extent to which these schools of thought became integrated into far-right extremist movements. In 1977 (a year before the NF propaganda first came to light), an American white supremacist group, the National Alliance (NA), published an article in its tabloid, The National Vanguard, titled “Sociobiology: The Truth at Last.” The NA is regarded by the Southern Poverty Law Center as “the most dangerous and best organized neo-Nazi formation in America” throughout the late twentieth century, and, compared to the NF, was demonstrably more genocidal in its platform, more effective at recruiting, and more violent in its actions.48 To my knowledge, the story of sociobiology’s role in shaping the NA’s platform has never been brought to light in scientific circles until now. One wonders how the scientific community’s tolerance for sociobiology and Jensenism may have changed if activist-scientists were aware of (and vocal about) how such research galvanized an organization linked to the murder of Jewish radio host Alan Berg in 1984, the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, the failed bombing attempt of a Martin Luther King Jr. Day parade in Spokane in 2011, and countless other hate crimes.

Simply buttressing the systems of scientific accountability is meaningless if we do not also contend with the material impact that weaponized science inflicts on society.

As the radical science movement began to deteriorate in the 1980s, so did the broader scientific community’s awareness of the far-right, which continued to warp and propagandize research in new and insidious ways. Despite its operational flaws, the radical science movement was the only voice bringing attention to the issue, and as its activism dissipated, the mainstream scientific community settled into ignorance and indifference. On the rare occasion that scientists did deign to respond to episodes of weaponized science, they tended to do so in a purely intellectual manner.49 These responses characteristically failed to acknowledge that such propaganda served a violent agenda, thereby precluding any deeper conversation about scientists’ obligation to act as agents of social change. A noteworthy example of this pattern of inaction surrounded the 1998 publication of David Duke’s autobiography, My Awakening, which drew heavily from the corpus of scientific racism to push for the resegregation of schools, among other line items on the standard ethnonationalist wishlist. Though most academics at the time would not have even bothered to dignify Duke with a scientific critique, the book produced a public relations debacle for the scientific community: the foreword to My Awakening was written by Glayde Whitney, a professor at Florida State University and president of the Behavior Genetics Association from 1994 to 1995. Whitney immediately came under administrative scrutiny (his federal grant funding was reviewed and the department arranged for him to take a year-long paid sabbatical), yet leadership at Florida State University and the Behavior Genetics Association preoccupied themselves with assuring the public that although Whitney’s endorsement of Duke was “disagreeable,” he was protected under principles of academic freedom.50

A Path Forward

Weaponized science continues to threaten far more than the public image of scientific authority. Today, it has morphed and evolved to find new victims and modes of victimization, and exploits whatever platforms and resources are at its disposal to promote its message.51 Synthesizing the lessons learned from past radical science movements provides us with a path forward: our collective response to weaponized science must be fiercely multimodal and operationally diverse, taking place in the pages of scientific journals, the digital streets of social media, and the physical spaces of our institutions and cities.

The first step in rebuilding this movement is for scientists to become deeply familiar with the sociopolitical milieu surrounding past and ongoing research in their fields. The Buffalo shooting, similar to the NF sociobiology propaganda, exposed the scientific community’s glaring ineptitude on this front—many (particularly those whose work was explicitly co-opted) viewed the shooter’s screed as a grotesque aberration of scientific illiteracy rather than a deeply philosophical and time-honored tradition of the global far-right. It is imperative that we understand far-right co-optation to be a systemic and ubiquitous outcome of scientific research. As other commentators have proposed, this outcome should be framed as a risk to be weighed against potential benefits when research is evaluated for funding, Institutional Review Board approval, and publication.52 However, these commentaries have placed the onus of enacting this reform on the doorstep of funding agencies, journals, and university administrations. Given the current climate in which many researchers insist that such reforms would infringe on principles of academic freedom, there is little reason to believe these hegemonies will meaningfully remediate scholarship that passively caters to far-right ideology. Instead, it falls on the members of the scientific community to build a robust body of collective knowledge about the audiences that are engaging with particular areas of research and how they are applying it in their daily lives. Put in a different way, the aim of this initiative is to develop, as a community, a means of empirically evaluating the “broader impacts” of research and holding one another accountable to that evidence. In the academic realm, this strategy has already begun to germinate. There is growing awareness of the extent to which the far-right consumes and weaponizes science,53 increasing scrutiny on fringe scholars publishing methodologically flawed research that panders to the far-right,54 and a strengthening movement of scientists who are genuinely motivated to deconstruct the perverted incentive structures that enable such research to persist.

Simply buttressing the systems of scientific accountability is meaningless, however, if we do not also contend with the material impact that weaponized science inflicts on society. Acts of violence like the Buffalo shooting are an extreme outcome of this impact, but more generally, far-right radicalization exhibits the characteristic patterns of a social contagion and a public health crisis that is endemic in society today.55 This epidemiological mindset warrants an entirely different framing of how scientists should address far-right appropriation of their research. Rather than treating distorted beliefs about biological determinism and genetic ancestry as symptoms of research that is poorly regulated and publicized, we must recognize weaponized science as a causal environmental factor that fuels and normalizes far-right ideology and perpetuates economic and health disparities for marginalized groups. The magnitude of these impacts demands far more of us than the proposed academic reforms, attempts at nuanced science communication, and superficial assurances of anti-racist solidarity that dominate the scientific community’s discourse. Instead, like the radical scientists active in the 1930s and 1970s, we must become deliberate, action-oriented community organizers and exert our own unique combination of expertise, privilege, social and professional connections, and geographic location to counter weaponized science on both sides of the ivory tower door. To this end, I leave readers with three challenges. First, we must further educate ourselves on the ecosystem of weaponized science. Second, we must actively resituate our appetite for scientific progress towards the service and liberation of our communities. Finally, we must channel this knowledge and desire for change towards the development and implementation of creative strategies to disarm weaponized science, inoculate against its normalization, build resilience and solidarity, and spread those ideas like wildfire.

—

Jedidiah Carlson is a population geneticist and meta-researcher based in Minneapolis. He holds a PhD in bioinformatics from the University of Michigan and completed his postdoctoral training at the University of Washington. As a geneticist, he is interested in how variation in germline mutation processes affect genome evolution. His meta-research focuses on developing novel scientometric strategies to quantify and characterize the societal impacts of contemporary scientific research.

Notes

- As summarized by “CERA Statement Against the Weaponization of Genetic Research,” accessed August 11, 2022, https://elsihub.org/news/cera-statement-against-weaponization-genetic-research.

- SSGAC (@thessgac), “We try hard to communicate in ways that won’t be misunderstood, but we have more work to do. Our efforts include writing and disseminating FAQs that explain how our findings should NOT be interpreted or used, including to compare European and African populations (FAQ 3.5),” Twitter, May 16, 2022, 10:17 p.m., https://twitter.com/thessgac/status/1526386447342870528; “IBG Statement in Response to the Buffalo Shooting,” Institute for Behavioral Genetics, University of Colorado Boulder, May 19, 2022, https://www.colorado.edu/ibg/2022/05/19/ibg-statement-response-buffalo-shooting.

- David Hugh-Jones, “On Nazis Who Read Genetics,” Wyclif’s Dust (blog), May 19, 2022, https://wyclif.substack.com/p/on-nazis-who-read-genetics.

- Robbee Wedow, Daphne O. Martschenko, and Sam Trejo, “Scientists Must Consider the Risk of Racist Misappropriation of Research,” Scientific American, May 26, 2022, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/scientists-must-consider-the-risk-of-racist-misappropriation-of-research/;Janet D. Stemwedel, “Science Must Not Be Used to Foster White Supremacy,” Scientific American, May 24, 2022, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/science-must-not-be-used-to-foster-white-supremacy/; C. Brandon Ogbunu, “Quashing Racist Pseudoscience Is Science’s Responsibility,” Wired, May 27, 2022, https://www.wired.com/story/quashing-racist-pseudoscience-is-sciences-responsibility/.

- Many of the calls for reform have explicitly focused on behavior genetics as being particularly prone to far-right appropriation. One of the deepest criticisms of research in this field is that it doesn’t consistently adhere to standards of scientific rigor held in other areas of human genetics, and in fact thrives on the controversy and publicity conferred by methodologically weak research. See Aaron Panofsky, Misbehaving Science: Controversy and the Development of Behavior Genetics (University of Chicago Press, 2014) and Ogbunu, “Quashing Racist Pseudoscience Is Science’s Responsibility.” Consequently, a common tactic used to defend such research is to conflate its critics’ calls for technical rigor with those critics’ stated (or perceived) ideological stance, thereby reshaping the fundamental norms of scientific critique into grounds for debate over academic freedom. With regards to the Buffalo shooting, an example of this tactic is perfectly encapsulated in Dan Hannan, “Don’t Let Violence Silence Science,” Washington Examiner, June 20, 2022, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/dont-let-violence-silence-science.

- Matthew McManus, “What is Post-Modern Conservatism?”, McGill International Review, March 30, 2018, https://www.mironline.ca/what-is-post-modern-conservatism/.

- Steven Rose, “Racism Refuted,” Nature 274, no. 738 (1978), https://doi.org/10.1038/274738a0.

- H. J. Eysenck, “Racism Refuted,” Nature 274, no. 738 (1978), https://doi.org/10.1038/274738b0.

- Arthur R. Jensen, “Racism Refuted,” Nature 274, no. 738 (1978), https://doi.org/10.1038/274738c0.

- “Sociobiology Critics Claim Fears Come True,” Nature 282, no. 348 (1979), https://doi.org/10.1038/282348a0.

- The Ann Arbor Science for the People Editorial Collective, “Announcement: Biology As A Social Weapon,” Science for the People 9, no. 5 (1977): 25, https://archive.scienceforthepeople.org/vol-9/v9n5/biology-as-a-social-weapon/.

- S. Rose, “Genes and Race,” Nature 289, no. 335 (1981), https://doi.org/10.1038/289335a0.

- John Maynard Smith, “Genes and Race,” Nature 289, no. 335 (1981), https://doi.org/10.1038/289742a0.

- Richard Dawkins, “Selfish Genes in Race or Politics,” Nature 289, no. 528 (1981), https://doi.org/10.1038/289528a0.

- mudlark121, “Today in London Anti-fascist History 1978: Blockade against National Front March on Brick Lane,” Past Tense (blog), September 24, 2018, https://pasttenseblog.wordpress.com/2018/09/24/today-in-london-anti-fascist-history-1978-blockade-against-national-front-march-on-brick-lane/.

- Mark Henderson and Philippe Naughton, “Scientist Griffin Hijacked My Work to Make Race Claim about ‘British Aborigines’,” The Times, October 23, 2009, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/scientist-griffin-hijacked-my-work-to-make-race-claim-about-british-aborigines-m5p5bn7sz0j.

- James J. Lee et al., “Gene Discovery and Polygenic Prediction from a Genome-Wide Association Study of Educational Attainment in 1.1 Million Individuals,” Nature Genetics 50, no. 8 (July 23, 2018): 1112–21, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0147-3.

- Lest this descriptive summary of the EA3 study’s aims be misinterpreted as an attempt to paint the authors as unassuming victims of far-right appropriation, I will direct readers to the wealth of criticisms of how behavior genetics as a field regularly endorses far-right talking points, such as Aaron Panofsky, Misbehaving Science: Controversy and the Development of Behavior Genetics (University of Chicago Press, 2014).

- A deeper discussion of why this is scientifically invalid can be found in Wedow, Martschenko, and Trejo, “Scientists Must Consider the Risk of Racist Misappropriation of Research.”

- Wedow, Martschenko, and Trejo, “Scientists Must Consider the Risk of Racist Misappropriation of Research.”

- This meme is modified from Figure 3B of Jinchuan Xing et al., “Toward a More Uniform Sampling of Human Genetic Diversity: A Survey of Worldwide Populations by High-Density Genotyping,” Genomics 96, no. 4 (October 2010): 199–210, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2010.07.004. Perpetrators of ethnonationalist terrorism often include frontispieces for their “manifestoes” and social media profiles that are designed to be particularly provocative and/or demonstrative of their ideology, such as gratuitous fascist imagery, self-portraits of the perpetrator in a skull mask and full paramilitary gear, etc. The Buffalo shooter featured a Nazi Schwarze Sonne (a specific form of a sonnerad, or “sun circle” designed by Nazi occultists and often used interchangeably with swastikas in neo-Nazi paraphernalia) on the first page of his screed, reflecting his admiration of the Christchurch, New Zealand shooter who used a similar image in his screed three years earlier. The presence of this meme on the Buffalo shooter’s Twitch profile (which he shared only with a small inner circle of other extremists) may suggest, disturbingly, that the shooter viewed it as having an aesthetic value comparable to that of Nazi symbolism. When asked for comment on the appropriation of this figure, the senior author of the Xing et al. study, Professor Lynn Jorde, expressed his gratitude for bringing this to his attention and referred me to a 2018 statement by the American Society of Human Genetics that he helped write, titled “ASHG Denounces Attempts to Link Genetics and Racial Supremacy.” He explained, “This statement summarizes my thinking, as well as that of virtually all human geneticists, on this issue.”

- Jedidiah Carlson (@JedMSP), Twitter, October 22, 2017, 7:16 p.m., https://twitter.com/JedMSP/status/922255315726368768.

- Eran Elhaik, “Why Most Principal Component Analyses (PCA) in Population Genetic Studies Are Wrong,” bioRxiv (April 12, 2021), https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.11.439381.

- Note that the plot was originally part “B” of a multi-panel figure in Xing et al.; the meme-ified forms of the plot retain this label

- For example, see Uncensored Science (@RealScienceNow), “The genetic reality of race,” Twitter, December 14, 2016, 4:19 p.m., https://web.archive.org/web/20220723192537/https://twitter.com/realsciencenow/status/809070301032185857.

- Experts on extremism stress that “online radicalization” is somewhat of a misnomer. Though the internet has become foundational in fostering far-right extremist content and networks, radicalization occurs through a combination of online and offline experiences. The radicalizing forces of far-right virtual spaces are often just exacerbating the conditions, beliefs, and behaviors already in place within an individual’s preexisting offline social environment. See C. Miller-Idriss, Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right (Princeton University Press 2020).

- Here, I refer to Susan Haack’s apt definition of scientism as “an over-enthusiastic and uncritically deferential attitude towards science, an inability to see or an unwillingness to acknowledge its fallibility, its limitations, and its potential dangers.” See Susan Haack, “Six Signs of Scientism,” Logos and Episteme 3, no. 1 (2012): 75–95, https://philpapers.org/rec/HAASSO.

- The earliest instances of scientific racism being explicitly used as state-sanctioned political propaganda predate 20th century fascist movements. During the American Civil War, the Confederacy sent a delegation to England with the task of drumming up support for the Confederate cause. Among this group was Henry Hotze, a Swiss-American who had previously translated into English Arthur de Gobineau’s sprawling tome of scientific racism, An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races. While in England, Hotze established “The Index,” a tabloid in which he frequently attempted to justify chattel slavery by applying Gobineau’s “scientific” ideas. Historians have credited Hotze as establishing “an anthropological tradition [of scientific racism] that would rise in prominence for the rest of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth.” See Robert E. Bonner, “Slavery, Confederate Diplomacy, and the Racialist Mission of Henry Hotze,” Civil War History 51, no. 3 (2005): 288–316..

- Robert E. Filner, “The Social Relations of Science Movement (SRS) and J. B. S. Haldane,” Science & Society 41, no. 3 (1977): 303–16.

- It was Bernal who coined the phrase “science for the people” in Marx and Science (Lawrence & Wishart London, 1952).

- J. D. Bernal, The Social Function of Science (Richard West, 1980).

- Brenda Swann and Francis Aprahamian, J.D. Bernal: A Life in Science and Politics (Verso, 1999).

- During the war, Monod joined the French Communist Party (specifically the Franc-Tireurs, or “Free Shooters” unit) as “a matter of obligation” so that he would have a say in how the organization was run rather than acting out of any meaningful ideological alignment (see Sean B. Carroll, Brave Genius: A Scientist, a Philosopher, and Their Daring Adventures from the French Resistance to the Nobel Prize (Crown Publishers, 2013). After the war, Monod became an outspoken critic of leftist scientists, despite supporting various leftist causes including the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, abortion rights, and the 1968 student protests in France. In his 1970 book, Chance and Necessity, Monod promoted what he called an “ethics of knowledge” that presupposes the epistemic domain is “intrinsically ethically justified” (see Natan Elgabsi, “The ‘Ethic of Knowledge’ and Responsible Science: Responses to Genetically Motivated Racism,” Social Studies of Science 52, no. 2 (April 2022): 303–23.). Monod’s philosophical stance—which was directly opposed to the dialectical approach of Marxist scientists—appears to have been punctuated by his signing of the “Resolution in Scientific Freedom” two years later, alongside Eysenck, Jensen, Herrnstein, and other race scientists (see Ellis B. Page, “Behavior and Heredity,” The American Psychologist 27, no. 7 (July 1972): 660–61.).

- Boas was active in a circle that has been described as “a colorful cast of unconventional thinkers,” “contrarian, fresh, and transgressive,” and “a network of marginals, argumentative and diverse.” See Ira Bashkow, “The Boas Circle vs. White Supremacy,” History of Anthropology Review, June 15, 2020, https://histanthro.org/reviews/the-boas-circle-vs-white-supremacy/.

- Bashkow, “The Boas Circle.”

- Zoe Burkholder, Color in the Classroom: How American Schools Taught Race, 1900–1954 (Oxford University Press, 2011).

- For a thorough account of this undoing, see Gary Werskey, “The Marxist Critique of Capitalist Science: A History in Three Movements?,” Science as Culture 16, no. 4 (December 1, 2007): 397–461, https://doi.org/10.1080/09505430701706749.

- Werskey, “The Marxist Critique of Capitalist Science.”

- Michelle Brattain, “Race, Racism, and Antiracism: UNESCO and the Politics of Presenting Science to the Postwar Public,” The American Historical Review 112, no. 5 (December 1, 2007): 1386–1413, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40007100.

- Brattain, “Race, Racism, and Antiracism.”

- Sebastián Gil-Riaño, “Relocating Anti-Racist Science: The 1950 UNESCO Statement on Race and Economic Development in the Global South,” British Journal for the History of Science 51, no. 2 (June 2018): 281–303, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007087418000286.

- However, as recounted by historian Gary Werskey, the story of this second generation of activist-scientists turned out to be “a comic mismatch between its political ambitions and historical fate.” Werskey’s historiographical perspective comes into particularly clear focus as we look back at how this generation of scientists approached the debates over Jensenism, and later, sociobiology.

- “A Resolution against Racism,” advertisement in The New York Times (October 28, 1973).

- Phil Czachorowski, “One Battlefront,” Science for the People 6, no. 2 (1974), https://archive.scienceforthepeople.org/vol-6/v6n2/one-battlefront/.

- “Notes from England: The New McCarthyism and the Rise of the National Front – Science for the People Archives,” accessed July 25, 2022, https://archive.scienceforthepeople.org/vol-10/v10n4/notes-from-england-the-new-mccarthyism-and-the-rise-of-the-national-front/.

- Jim Dann and Hari Dillon, “The Five Retreats: A History of the Failure of the Progressive Labor Party,” Marxists Internet Archive, accessed August 23, 2022, https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/1960-1970/5retreats/.

- Dann and Dillon, “The Five Retreats.”

- “National Alliance,” Southern Poverty Law Center, accessed August 16, 2022, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/group/national-alliance. The NA’s founder, a physicist named William Luther Pierce, published the novel The Turner Diaries in 1978; this book is widely regarded as “the bible of the far-right” and has been connected to “at least 200 murders, committed in 40 terrorist attacks and hate crimes.” See Johnathon Kelso and Seyward Darby, “The Father, the Son and the Racist Spirit: Being Raised by a White Supremacist,” The Guardian, March 31, 2021, https://amp.theguardian.com/world/2021/mar/31/william-luther-pierce-white-supremacist-son-kelvin-pierce. Though The Turner Diaries does not even tangentially mention concepts of sociobiology and scientific racism, other far-right writers acknowledge that Pierces’ embrace of sociobiology was deeply instrumental in establishing his intellectual credentials and expanding his platform among the far-right. See Theodore J. O’Keefe, “Review: The Life and Legacy of William Pierce,” The Occidental Quarterly, 2003, https://www.toqonline.com/archives/v2n4/TOQv2n4OKeefe.pdf.

- The most notable examples of this response revolved around books that reignited the popularity of scientific racism, such as Herrnstein and Murray’s The Bell Curve (1994), Richard Lynn’s IQ and the Wealth of Nations (2002), Cochran and Harpending’s The 10,000 Year Explosion (2010) and Nicholas Wade’s A Troublesome Inheritance (2014).

- Writing about the affair in Salon in 1999, journalist Chris Colin bemoaned the perpetual cycle of racist invocations of science being countered entirely by scientific rebukes that were footnoted by cursory charges of racism. Colin mused that “perhaps the more effective response would be an overhaul of America’s race consciousness to the point where no genetic research has the power to disrupt lives.” (see Chris Colin, “Reading Genes in Black and White,” Salon.com, April 26, 1999, https://www.salon.com/1999/04/26/genetics/.).

- For example, using genetics and neuroscience research to justify attacks on the trans community or using ecology and conservation research to justify ecofascism.

- Wedow, Martschenko, and Trejo, “Scientists Must Consider the Risk of Racist Misappropriation of Research.”

- Jedidiah Carlson and Kelley Harris, “Quantifying and Contextualizing the Impact of bioRxiv Preprints through Automated Social Media Audience Segmentation,” PLoS Biology 18, no. 9 (September 22, 2020): e3000860.

- Monika Pronczuk and Koba Ryckewaert, “A Racist Researcher, Exposed by a Mass Shooting,” The New York Times, June 9, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/09/world/europe/michael-woodley-buffalo-shooting.html; J. Philippe Rushton and Donald I. Templer, “RETRACTED: Do Pigmentation and the Melanocortin System Modulate Aggression and Sexuality in Humans as They Do in Other Animals?’ [Pers. Individ. Differ. 53/1 (2012), 4–8],” Personality and Individual Differences 175 (June 1, 2021): 110726.

- Mason Youngblood, “Extremist Ideology as a Complex Contagion: The Spread of Far-Right Radicalization in the United States between 2005 and 2017,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7 (2020): 49, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00546-3; U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Foreign Affairs, Meeting the Challenge of White Nationalist Terrorism at Home and Abroad, 116th Cong., 1st sess., September 18, 2019, serial 116, 63, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-116hhrg37706/html/CHRG-116hhrg37706.htm.