A Cry for Decolonization

How climate policy must imagine different futures

By Aditi Bansal & Quynh Le Vo

Volume 24, Number 1, Racial Capitalism

June 21, 2021

Lee este artículo en español aquí / Read this article in Spanish here.

“What I know is that all empires fall and every empire is a story and holds within it the poem of its own unraveling.”

—Alexis Pauline Gumbs1

Imagination is inseparable from policymaking. A desirable future must first be imagined to design policies that can reach it.

Goals for tackling climate change are often defined in numerical terms, such as the Paris Agreement’s target of limiting global warming to “well below 2°C, compared to pre-industrial levels.”2 While science-based policymaking is crucial, the preoccupation with statistics and projections in this numbers-centered approach to climate action undermines decision-makers’ ability to critically examine imaginaries of the future.

Climate activists, especially those who have been disenfranchised, marginalized, and forced onto the frontlines of climate disasters, have long called for a complete overhaul of the global capitalist system at the root of the crisis: “system change, not climate change.” Instead of focusing on numerical targets, the aim of climate action must be to create just and regenerative societies for all, starting with the most vulnerable, marginalized populations.

Climate action, and the futures we imagine, must be re-examined, re-framed, and re-conceptualized.

The climate target sham

Government and corporate climate pledges exemplify the dominance of the numbers-centered approach. Their targets of carbon neutrality have far-off deadlines, such as “net-zero by 2050,” but lack operable near-term plans. Every non-committal pledge and toothless corporate press release displays a form of climate “delayism” that distracts from meaningful and immediate climate action.3 Inherent to some of these climate pledges is the assumption that burning fossil fuels in the upcoming decades is practical since carbon capture technologies and geoengineering—unproven and with potentially dangerous repercussions—will remove additional carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in the future. Furthermore, the reliance on carbon sequestration for meeting these targets often does not include an analysis of whose land will need to be occupied, where this land is located, and who will benefit the most.

Climate action, and the futures we imagine, must be re-examined, re-framed, and re-conceptualized.

Built on the idea of an optimal level of warming prevalent in environmental economics, these pledges are calculated to balance the costs and benefits of fighting climate change. These supposedly objective calculations are framed from the Global North’s perspective, while ignoring that the Global South and frontline communities worldwide already experience devastating consequences.

In the dominant Global North imaginary, tackling climate change requires the decarbonization of the energy system. Fixating on this particular aspect of the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions justifies the Global North’s continuing extractive and exploitative relationship with the Global South and BIPOC communities.

In the Nordic countries of Norway, Sweden, and Finland, construction of wind energy and hydropower plants is taking place on indigenous Sami territories without local consent. This corporate activity disrupts the practice of reindeer herding, a Sami traditional livelihood that is the basis for both their economic and cultural survival.4

The production of batteries,5 solar panels, and wind turbines to meet current energy demand also requires a massive increase of already high levels of current material extraction. Many of these mineral deposits are found in Global South countries, such as Chile, Argentina, and Mexico, where the extractive industry already poisons waterways, destroying ecosystems and forcing farmers to abandon their lands.6 Companies supplying solar panels for US and European renewable energy projects have also been linked to forced labor among China’s ethnic Uighur minority in Xinjiang.7

Just as capitalism values wealth accumulation over human life and ecological limits, the numbers-centered approach values technological development, limitless extraction, and exploitation over creating an egalitarian future. The Global North’s fixation on decarbonization values growth over justice, maintenance of current levels of consumption and hegemonic power, and technological, neocolonialist solutions over building regenerative relationships with nature and communal well-being—a perpetuation of colonialism and racial capitalism.

This is not an accidental feature of climate policy, but rather the direct result of capitalist imaginaries fundamental to current policymaking. As noted by Ben Ehrenreich in The New Republic, “A strange sort of faith lies at the core of mainstream climate advocacy—a largely unexamined belief that the very system that got us into this mess is the one that will get us out of it.”8 Without an overhaul of these imaginaries and systems, the numbers-centered approach all but guarantees that only a few will reap the benefits of a “cleaner” environment, while the low income, BIPOC communities of the world will continue to be relegated to the frontlines.

Dystopia realized

Tamanna is strolling around the Ludhiana9 zoo with her parents, oohing and aahing at the various mammals. She is particularly enchanted with India’s national animal, the Bengal tiger. She has placed herself as close as possible to the chain-linked, savanna-like habitat where Raja is lazily swatting flies away with his tail. She counts the stripes on his back and wonders whether Raja has any cubs she can take home as her pet.

The monsoon has a tight hold on the air. Tamanna’s parents quickly pull her away from the tiger sanctuary and move to their heavily air-conditioned car. As they drive away, the seven-year-old has begun plotting a life plan dedicated to counting the stripes on Raja’s back, finding his cubs, and learning his life story.

The sky breaks.

Tamanna is in a small boat, deep in the Sundarbans mangrove forest with a local guide. The intense humidity in the forest is worsening her jet lag. She is leading a biodiversity mapping expedition. The local guide, Som, uses a mix of Bangla and Hindi to explain how the ecosystem has drastically changed with the increase in flooding. The most recent flood in 2030 ravaged his farm, leaving him to rely upon the waning tourism industry. She asks whether Som has seen many tigers in the mangroves recently. He hesitates to admit that he has seen none.

As Tamanna’s vision shifts again, she realizes she’s dreaming.

She is thirteen years old, and her family is immigrating to Australia. As she packs up all the books she’s collected on the big mammals of South Asia, she’s excited about the prospects of seeing and learning about Australia’s wildlife. When her papa shared the news about the big move, he had prefaced it with pictures of koalas, kangaroos, wombats, and platypuses—those really caught her eyes. But the fear of separation from her home, her grandparents, her cousins, her friends, and her beloved zoo have been drenching her belongings in tears and prolonging her efforts to pack up her life.

The droughts in Punjab have gotten worse and the COVID-19 pandemic has ravaged the agricultural community. The Indian government has refused to support the farmers, favoring big corporations instead. The family of laborers who work on her parents’ farm are being forced to return home to their village in Chhattisgarh. The father of the family has joined the farmers’ protests taking place in Delhi.

Their daughter, Asha, is another reason why Tamanna cannot imagine leaving Ludhiana. One could call them childhood friends, but they are more like sisters. Although they lead very different lives—Asha’s time is spent taking care of her siblings and household chores, while Tamanna’s only responsibility is finishing her homework on time—they share a love for a fictional world the two had created at a young age, where all animals roam free and there are no adults dictating the ways of the world.

As she dreams of seeing burnt koala bears and kangaroos, with echoes of farmers chanting, “Kisan ekta, zindabad,”10 she wakes up drenched in sweat, realizing that her dystopian dream was her actual past.

It’s 2050. Tamanna is back in Punjab.

Sirens blaring urge her out of bed.

She’s tired of telling world leaders to stop burning fossil fuels as the biodiversity of the planet she loves has been eradicated by unfettered growth. Asha and her family didn’t survive after their arduous departure from Punjab to Chattisgarh. She recalls learning that Asha’s father was killed by the Delhi police when the farmers’ protest turned violent on Republic Day, January 26, 2021. She finally understood that not only biodiversity was endangered in the face of the climate crisis, but so were the lives of working-class people. Her spirit and heart have been broken time and again by the world. Being back in her childhood home is a poignant reminder of how her world has spiraled towards a ghastly fate.

She walks to the bathroom in a daze, wondering when she will have water to shower next, as the cycle of existential crises and doom continues.

Matrix of imaginaries

The foundations for alternative imaginaries exist.

Concepts of buen vivir in South America and ubuntu in southern Africa draw from indigenous traditions and reject the separation of humans from nature imposed on communities through colonialism and the neoliberal development agenda. Instead, relationships are built on principles of reciprocity, communalism, redistribution, solidarity, and nurturing. These ideas combine notions of degrowth with critiques of extractivism to offer a low-carbon, eco-sufficient and anti-capitalist alternative.11 12

In the Peruvian Andes, a grassroots network of organizations called PRATEC (Proyecto Andino de Tecnologías Campesinas) has been working with indigenous communities since 1986 to support and strengthen local practices and ways of knowing, challenging the vision of technology-driven and market-oriented development and progress.13

Peasant community movements, like Nayakrishi Andolon in Bangladesh and MASIPAG in the Philippines, combine traditional knowledge with advances in science in their biodiversity-based agricultural production. Their practices center conservation and regeneration, as well as people’s control over seeds and genetic resources in resistance against multinational fertilizer, pesticide, and agricultural companies.1415

Similarly, campaigns for energy sovereignty aim to decolonize the hegemonic, privatized model of energy production and to decentralize and localize energy generation, technology, and knowledge.16 In Costa Rica, four large rural electricity cooperatives are owned and operated by energy users and community members. The cooperatives provide local jobs and ancillary services, while also supporting community initiatives that preserve the natural environment.17

We must center the eradication of the racialized effects of colonialism and capitalism in the imaginaries that guide all climate policy making and action.

Initiatives, such as the Global Tapestry of Alternatives,18 Beautiful Solutions,19 and Vikalp Sangam,20 provide building blocks for a just, resilient, and democratic future. Rather than dictating a singular way out of the dominant capitalist, racist, and patriarchal regime, the communities profiled by these initiatives present a matrix of alternatives based on shared values and visions for the world.

As Indigenous academic and activist Nick Estes says, “We need a revolution of values that re-centers relationships to one another and the earth over profits.”21 BIPOC and working-class people of the world who represent the feminist and decolonial traditions must be the leaders of this revolution. Degrowth and decarbonization must be linked; “keep fossil fuels in the ground” must no longer be dismissed as quixotic. We must center the eradication of the racialized effects of colonialism and capitalism in the imaginaries that guide all climate policy making and action.

Another world is possible

Asha is bent over a patch of land lined with cauliflower, beans, and eggplants. She is diligently harvesting in preparation for dinner. As she hums the lullaby her mother used to sing to her, she feels nostalgic and wishes her mother could have witnessed the transformation their ancestral land and tribe had undergone in the past thirty years. Her amma22 was the one who named her Asha, meaning hope in Hindi. In all her imaginaries for the future, she had never expected to live up to her namesake.

Things had looked different in 2020, when Asha, her amma, and three siblings returned to Hasdeo Arand, a biodiverse, protected forest and her family’s ancestral home in Chhattisgarh after the family whose farm they worked on in Punjab moved away. Her father had left to join the farmers’ protests in Delhi.

Soon after their return, the Indian government granted permits for coal mining in the forest. At the time, this seemed like a positive development to Asha and her mother; they were in desperate need of money and sought employment from the mining companies.

Their employment at the coal mine did not last long. After six months, her amma died of COVID-19. Until that moment, Asha had been in survival mode, but, as she mourned her amma’s passing, she realized that the world didn’t want people like her to survive.

Even now as she picks vegetables into her basket, Asha can remember the deep sense of despair and anger she felt after losing her parents. From her appa23 losing his livelihood as a farmer to her amma losing her life, Asha had realized that both of those losses had been at the hands of the corrupt government, greedy corporations, and wealthy, upper-caste elites who used people like her family for their own selfish profit motives. For as long as she could recall, her parents had been overworked, underpaid, and exploited.

Struck by this reality that she had suppressed her whole life, Asha decided to fight for her people: the Gond people–the tribe she belongs to—all the people working in the coal mines of Hasdeo Arand, and all the tribes who were forcefully evicted from their ancestral lands by the government’s destructive focus on energy independence.

Five years later, the andolan24 to bar all coal mining operations from Hasdeo Arand succeeded. The andolan even won forest rights. The long fight against many powerful people had ended. National and global attention and support had waned. The tribes and community of ex-coal miners had started rebuilding a new life. Some were returning to the forest.

Tribal elders were leading efforts to rehabilitate land, water, and biodiversity, and establish new forms of communal responsibility, governance, and care. The elders brought everyone together to share their way of living—one in sync with their shared ecosystem and their non-human kin. They also wanted to learn how the skills, ideas, and visions for the future of each person could be brought together. The community decided to begin teaching the young and future generations the myriad ‘lost’ tribal languages, tribal and land sovereignty, and indigenous knowledge and traditions.

As the climate crisis had raged on for the past decade, networks of mutual aid had spread across the nation out of necessity. The Indian government and its private beneficiaries were being dismantled by this human mycorrhizal network through massive worker strikes, tax resistance, and demands for cancellation of external debt.

Tribal elders were leading efforts to rehabilitate land, water, and biodiversity, and establish new forms of communal responsibility, governance, and care.

By 2030, the Hasdeo Arand community was sovereign, and connected to other sovereign communities in India. They were rebuilding relationships to ensure sustainable practices and the ability to exchange knowledge. Their sense of economy and sustainability was communal. They had established a matriarchal system of governance and sustained themselves with the land, biodiversity, and natural resources available. They designed and built a repair and recycle program that supported a community solar power system in the forest.

Asha was thirteen when she lost her mother. It shifted her vision of the future. When she started fighting against corporate greed and global pressures of industrialization, she imagined becoming a part of the land by rebuilding her relationship to it. She imagined existing outside of the exploitation of growth and development empires. She imagined living with a sense of history of her people and their fight for justice. She imagined a better future for her siblings, her tribe, and her ancestral land.

It is 2050. Asha reflects on the last two decades as she revisits an old journal entry and is struck by how much her world has moved:

“After much trial and error, we’ve designed several micro-grids supported by recycled solar panels. It took a lot of effort to find used batteries for storage and resilience, but the effort became a great foray into creating a community class for repair. Now we have a dedicated group of elders and youth who are responsible for teaching and ensuring that we continue being energy independent. Using permaculture farming methods, this patch of land has become sort of a test kitchen to figure out a sustainable combination for energy, land, and sustenance for our community and non-human kin. The best part is that the land is shared with our non-human kin, not just cows or goats, but we’ve also seen elephants, leopards, and sloths. I think Tamanna would love to see all the kin who have come back to the forest.

I found some old journals and notes from when my tatta25 and appa were farming this land. It’s a part of my legacy that I thought I had lost. I can now bring it back to life on the same land that they called home for centuries.”

She has spent her lifetime with her community in the fight to rebuild a regenerative, just society. She is now part of a cooperative, freeing her concerns of exploitation. She spends her day caring for her people, farming the land, cooking, and raising everyone’s children.

About the Authors

Aditi Bansal, MSc, is a climate justice advocate with a passion for just energy transition. Her graduate studies focused on building resilient energy systems in resettlement camps. She specializes in policy research and development. Her other activism interests include decarbonization, indigenous sovereignty, and energy democracy.

Quynh Le Vo holds a BSc in International Relations from the London School of Economics and Political Science and is currently completing a master’s in environmental change and global sustainability at the University of Helsinki, focusing on climate adaptation in Southeast Asia. Born in Vietnam, she has subsequently lived in Hungary, Finland, the UK and the US. Previously, she has worked for the Permanent Mission of Finland to the United Nations, covering environmental and development issues. Twitter: @quynhlevo

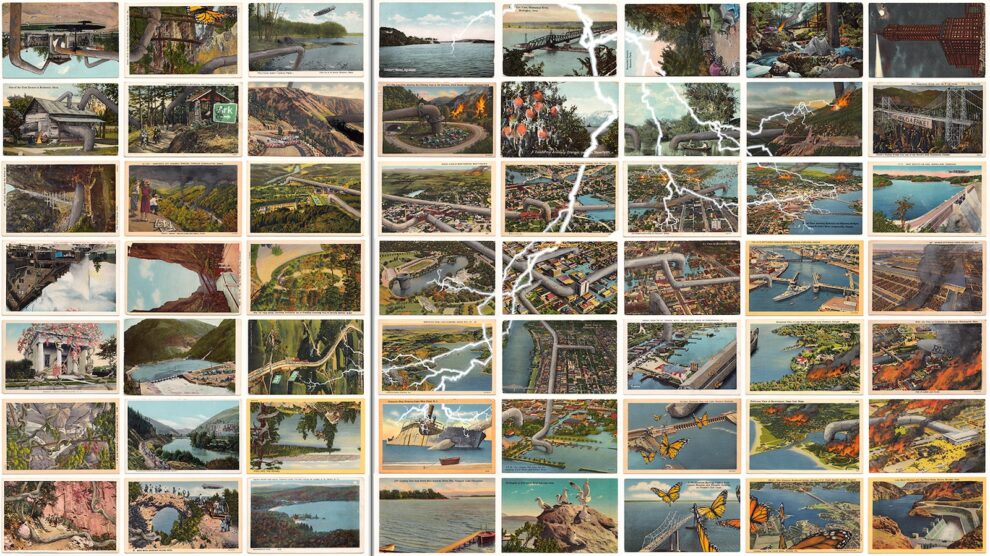

About the Artist

Dina Farone, MA, is a freelance graphic designer and illustrator with a focus on climate and environmental topics. She received her master’s degree in Climate and Society from Columbia University and is the owner of Net-Zero Farms, a sustainable farming start-up. Website: dinafarone.com

References

- “At Home With Hortense Spillers and Alexis Pauline Gumbs,” Zalaznick Reading Series, November 10, 2020, retrieved March 21, 2021, from https://ecornell.cornell.edu/keynotes/overview/K111020/

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, “The Paris Agreement,” December 12, 2015, accessed January 26, 2021, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement.

- William F. Lamb et al., “Discourses of Climate Delay,” Global Sustainability 3 (2020): e17, https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2020.13.

- Society for Threatened Peoples (STP), “Sami Reindeer Herders Threatened by Green Energy Projects,” Minority Monitor, June 8, 2019, https://www.minoritymonitor.eu/case/Sami-Reindeer-herders-threatened-by-green-energy-projects.

- Center for Interdisciplinary Environmental Justice, “No Comemos Baterías: Solidarity Science Against False Climate Change Solutions,” Science for the People 22, no. 1 (Summer 2019), https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/vol22-1/agua-es-vida-solidarity-science-against-false-climate-change-solutions/.

- Jason Hickel, “The Limits of Clean Energy”, Foreign Policy (blog), September 6, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/09/06/the-path-to-clean-energy-will-be-very-dirty-climate-change-renewables/.

- Ana Swanson and Christopher Buckley, “Chinese Solar Companies Tied to Use of Forced Labor,” The New York Times, January 8, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/business/economy/china-solar-companies-forced-labor-xinjiang.html.

- Ben Ehrenreich, “We’re Hurtling Toward Global Suicide,” The New Republic, March 18, 2021, retrieved March 19, 2021, https://newrepublic.com/article/161575/climate-change-effects-hurtling-toward-global-suicide

- A city in Punjab, India.

- “Long live farmer unity” in Hindi.

- Juan Francisco Salazar, “Buen Vivir: South America’s Rethinking of the Future We Want,” The Conversation, July 24, 2015, http://theconversation.com/buen-vivir-south-americas-rethinking-of-the-future-we-want-44507.

- Lesley Le Grange, “Ubuntu,” in Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary, ed. Ashish Kothari et al. (New Delhi: Tulika Books and Authorsupfront, 2019), 323–26.

- Kelly Teamey, “Development = Cosmovision and Crianza… Learning from PRATEC,” Enlivened Learning (blog), February 1, 2013, https://enlivenedlearning.com/2013/02/01/development-cosmovision-and-crianza-learning-from-pratec/.

- “About MASIPAG,” masipag.org, 8 April 2013, https://masipag.org/about-masipag/.

- “Nayakrishi Andolon: A Short Introduction,” UBINIG, November 26, 2017, https://ubinig.org/index.php/nayakrishidetails/showAerticle/2/46/english.

- Daniela Del Bene, Juan Pablo Soler, and Tatiana Roa, “Energy Sovereignty,” in Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary, ed. Ashish Kothari et al. (New Delhi: Tulika Books and Authorsupfront, 2019).

- Daniel Chavez, “COOPELESCA, Costa Rica,” Energy Democracy (blog), December 12, 2016, https://energy-democracy.net/coopelesca-costa-rica/.

- “An Introduction to the GTA,” Global Tapestry of Alternatives, accessed February 10, 2021, https://globaltapestryofalternatives.org/introduction.

- ‘Beautiful Solutions | This Changes Everything’, Beautiful Solutions, accessed February 10, 2021, https://solutions.thischangeseverything.org.

- ‘Vikalp Sangam’, Vikalp Sangam – Alternatives Confluence, accessed February 10, 2021, https://vikalpsangam.org/.

- Nick Estes, “A Red Deal.” Jacobin, June 8, 2019. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/08/red-deal-green-new-deal-ecosocialism-decolonization-indigenous-resistance-environment.

- “mother” in Tamil.

- “father” in Tamil.

- “protest” or “resistance” in Tamil

- “grandfather” in Tamil.