Science, Feminism, and Black Liberation: An Interview with Sam Anderson

Part 1

By Emily Hamilton

Volume 23, number 1, Science Under Occupation

This interview is co-published with Black Perspectives.

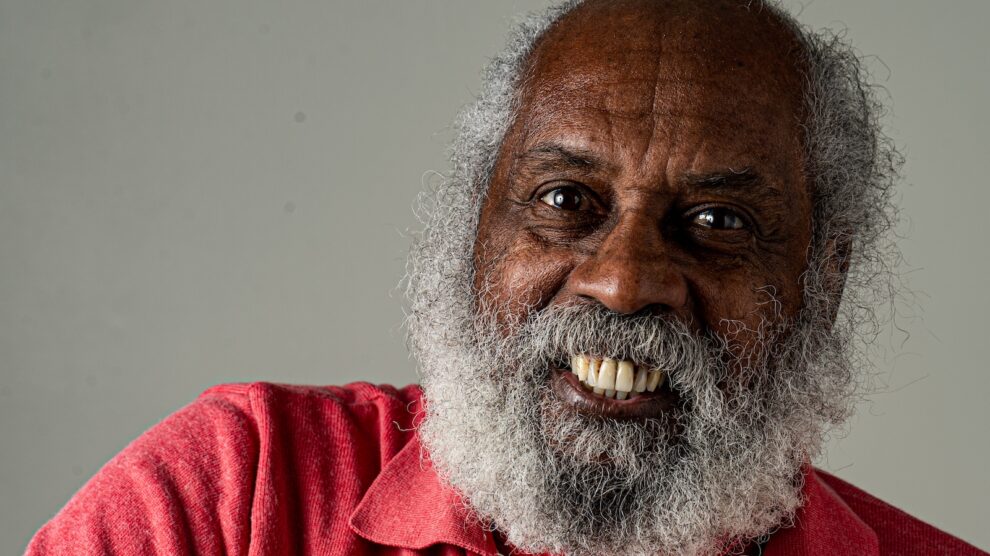

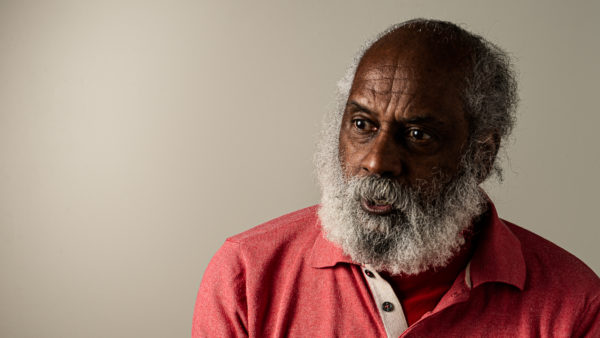

Emily Hamilton interviewed Sam Anderson over several days in early December, 2019. Emily is a professor of history and studies mathematics education reform. Sam is an activist, scholar, author, and early member of Science for the People. See their full bios on our contributors page. This interview has been edited for length and clarity by Erik Wallenberg and Saman Sepehri. This is a multipart interview, read part 2 on our website.

In this interview, Sam takes us into the history of his activism. His memory is a rich tapestry of the people who made an era, part of the collective story of SUNY Old Westbury, Harlem, and of course, Science for the People. In this third issue since the magazine’s relaunch, and the fifth year since our revitalization, we are weaving a new tapestry, which is made stronger and more vibrant by including stories from our past.

Emily Hamilton: Can you tell me about the history, the original mission, and members of Science for the People?

Sam Anderson: The original mission comes out of the anti-war movement primarily, and it evolved into something larger than the anti-war movement in relationship to the military industrial complex dominating in academia and in the science and engineering fields. And some of the younger science majors in undergraduate and graduate school were interested in doing something other than corporate research, corporate science, corporate engineering, rationalizing, teaching the way science and technology was taught in the colleges and universities. So there was a lot of frustration, I think, growing out of the revelations that the [movement against] the Vietnam War created.

In 1968, students discovered the deep collaboration between academics and administrators at Columbia University and the work within the US military at various levels of the CIA, Secret Service, FBI, all in Low Library. There were documents that were found and exposed and that helped spark a few of the founders of Science for the People. It had another name, [Scientists and Engineers for Social and Political Action, or SESPA] and it flourished in 1968. 1968 was a most tumultuous year and Columbia University was the epicenter for activists who were involved on the educational level. A lot of the inspiration came out of the young people who were exposing the collaboration between the science, technology, and engineering intellectuals and administrators with the military industrial complex to push Agent Orange, among many other things.

EH: You have demonstrated a long history of activism in Science for the People, but also outside it. Did this activist work shape your involvement with Science for the People? Can you tell me more about how you originally got involved?

SA: Absolutely. Yes, it did. I knew of the formation early on. In 1970, I was part of a major experiment in creating a four-year college in the United States from scratch, the college at Old Westbury, part of the State University of New York (SUNY). And it was there that we had the opportunity, because it was a critical mass of progressives who were designing the four-year institution, of raising the issue of what is science, what is science education, who is science working for? Why are there so few people of color involved in the sciences in the United States? And what can we do about it? At a four-year institution that we are in control of, literally, the curriculum and hiring and so forth. And so that was a big thing. We had communications with a couple of the early founders of Science for the People by way of Paul Lauter and John McDermott, a professor in philosophy and political science. And then I, within that academic year, ran into Professor Maurice Bazin, a French physicist who was the third person to sit in the Chair that Einstein had at Princeton. The Vietnam War brought us together at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). And the Vietnam War radicalized him and he did a thing that blew people’s minds in academia. He left Princeton. He left that Chair. He left Princeton and went to Rutgers and began to teach at the women’s college there [Douglass College].

And we became real good friends and stayed in touch over the years. That was another thread that led to [our] Science for the People work. We would attend some of those AAAS meetings, just to disrupt them, as representatives of Science for the People. We had the opportunity, maybe 1974, of being on WBAI, critically interviewing the then-Chair of the AAAS [Glenn T. Seaborg] who was a staunch supporter of war science, war-related research in the sciences. And some people called in and said that we were being too harsh on him, [saying] he’s a scientist, he’s just doing his work, and so forth and so on. And that was coming from progressives. We did that to expose his collaboration with the government on some of the horrible stuff, particularly Agent Orange. What we did not do, which we should have, was to write up a piece for Science for the People.

The other thread was Marilyn Frankenstein, who is a mathematician. And she began to do a lot of anti-racist, feminist kind of work in the sciences and had connections with many of the Science for the People forces in the Boston area. As you know, Boston has a number of universities and a number of those university students became active members in and around Science for the People.

Working in this milieu at the College of Old Westbury, we felt that what we were doing was groundbreaking. We did not have departments. What was the role of departments within a capitalist educational system? It was a divisive role. It was not a pedagogically sound role. So we had areas of study, programs. I was chair of the Science and Technology Program. But the school also had a mandate to provide nurses and pre-med students to feed into the new growing SUNY Buffalo and SUNY Stony Brook. The way they designed the colleges [was to] have a feeder into the various areas of study. So we decided that you had this science and technology program and you had a parallel program in the “health sciences” in order to facilitate these nursing students and pre-med students. That was headed by a Black chemist, Sam Von Winbush, and I headed the science and tech, which was highly unusual in that period—to have people of color in that kind of position in the sciences.

EH: Who were some of the other founding members of the Old Westbury program?

SA: [Beyond] Sam Von Winbush, Paul Lauter, and John McDermott, there was Florence Howe, who founded Feminist Press, Gloria Young Sing who was in political economy, Angela Gilliam who was an African-American linguist who spoke multiple languages. She was in fact the one that got me to come to Westbury. Peter Kwong was a Chinese American political economist who did a lot of pioneering work in the area of Asian studies. Barbara Ehrenreich who went on to write the book Nickel and Dimed. There were a group of feminists who Florence was able to get hired there who went on to do a lot of work. Many stayed for several years at Old Westbury, but many went on to other things, several who helped shape, what we call today, feminist studies.

Old Westbury was a very advanced community. We had to build from scratch, both physically and in the academic realm. So physically, what happened was the dormitory was co-ed. We recruited relatively older students, so the median age in the first several years was twenty-seven for the students and it was mainly women and we had one third Black, one third white, one third Latino, and others. And we had part of the dorms set aside for couples, and it didn’t make any difference whether they were same-gender couples or not. Right. So that is 1970, this is like out there. You had older people, so they had children, you know. So we had a free childcare center, fully professionally developed and run on the campus.

And we were able to do that because Governor Rockefeller had this vision of creating a world-class university system. Old Westbury was set aside as the experimental school, the school to do the experimental work in academia. I came in with a number of other people in very late 1969, early 1970, to rethink it. And it just so happened that it was a critical mass of progressive faculty members who came together. We had some liberal conservative faculty members, but they were outnumbered by this progressive group. And so since you are the founding faculty, you start to hire. And so you have control over who was coming in and one of the things we mandated was that we will never hire adjuncts (part-time [faculty]). Everybody we hire was going to be full time because even back then, we sort of understood that the more adjuncts you have, the less esprit de corps you would have, the less comradeship. Because those people [are coming] in and out, they don’t relate, they hardly relate to the students and so forth. So we didn’t want that to happen at all. So we had control of all that for, I would say, about eight years. And then the SUNY bureaucracy and the president start to make inroads. It got to be ironic, I guess, that several years later, my wife winds up teaching as an adjunct at Old Westbury, which is something that we vowed would never happen.

EH: While you were involved with the original Science for the People group, were there issues that you thought the members should be tackling and they weren’t? Did you see any weaknesses with the group or particular strengths?

SA: The big weakness was not having a critical outreach to people of color, particularly in academia, because they were mostly based in the universities, not so much in industry. You would provide them with, “hey, there is Professor so-and-so over here who is interested in doing work with you. Contact them and try and follow through. And he or she might be able to get some students involved in it” and so on. And that was not happening.

The strong point, I think, was the inclusion of women as equals in the organization. Even though there was, you know, a lot of male chauvinism going on, it was a fight. It was a battle. It was productive. I think the effort to bring some of these complex scientific ideas down to everyday folk in the writings and in some of the organizing is also very good. And I think that was particularly inspired or rooted in the anti-war work that people were doing and exposing that capitalism uses science to oppress people. Capitalism uses science to divide the American citizenry, and so forth. You know, that kind of thing was very good work that they had done. I think the growing work on the international level was important, even though I don’t think they did enough of that. But particularly in the Western Hemisphere, it was still important not to see yourself as scientists just focused here in the US, but begin to make that connection on an international scale. I think some of them went on a trip to Cuba. Formally there might have been a report in one of the issues on that trip, which would have happened in the late 1970s.

Also, Science for the People did use pre-social media very well. With the magazine, with the development of the smaller conferences, some of the regional conferences and what have you, I thought that was something very useful in deepening and broadening Science for the People. And again, that goes back to the struggles, the internal struggles that they had ideologically, and the struggles that women had in claiming equity in the organization. That evolved positively over the years. And I think that was, again, the impact of the powerful feminist movement in that period. To me the height of the feminist movement was from the latter part of the sixties to the early part of the eighties. That period, you know, feminism really pushed all of the progressive structures, organizations that were existing and those that came into being in that period, it made a big difference in a positive way.

EH: What’s your role with this rebirth of Science for the People?

SA: I’m on the sidelines again of the new rebirth. At first I was trying to get myself involved deeply in it, but then a lot of other political work—you know, you have to make a choice—came in and I had to deal with that in terms of the downswing of the Black liberation movement. It took up a lot of my time. My vow in 2020—to get more involved, definitely. Say no to some things over here and say yes to some of the Science for the People work. And I think my role is going to be to bring in those young people of color who are in the field, that have no idea that this body exists, and would feel like “this is what I’ve been looking for and want to get involved.”

EH: I know that you see science, technology, and math as central issues for Black liberation. How did your thinking on that relate to the work you were doing in Black studies and the Black liberation movement? How did those combine for you?

SA: In my head, if we were going to have a liberated US, Black people, people of color will be not just in certain types of jobs. They will work in all fields. And it’s essential that in this period of the sixties that the Black liberation movement understand this, that moving forward in a revolutionary change in the United States, you also have to be cognizant of the developments in the fields of science and technology. If you’re not directly involved in it, then others will be defining what science and technology is and who can do science and technology in a [society] increasingly more dependent on science and technology.

And at the same time, we had this big push in the sixties for Black Studies programs on campuses. What I was advocating was that every Black Studies program should have some sort of science component to it, either history of science or collaborative science work. But it was hard to get non-science folks to understand that. Most of the people who were developing and advocating for Black studies programs on campuses were social scientists who, if they had any contact with math and science, it was trauma. So they didn’t understand the interconnectedness of all of the physical sciences and mathematics to the social struggles. I did a short essay that came out in The Black Scholar in 1970, called “Mathematics and the Struggle for Black Liberation.” And for most people it was like cognitive dissonance. What is this, I don’t see the connection.

EH: Why is it important to bring science to the people?

SA: If we have a science for profit and for capitalism, it will continue down the road of helping fascism and totalitarianism—whatever you want to call it—forms of oppression to continue to build and overpower us. And we need to have the sciences in the hearts and minds and hands of ordinary, everyday people in order to counter that move that we are already beginning to see—particularly around the issue of climate change—where the capitalist forces find all kinds of ways to undermine the fight back against the climate crisis.

The capitalist system is based on inequity and inequality. It’s got to have that in order to exist. But we fight. We bring those ideas out. We advocate for them. We fight for that. We build on whatever little victories we have, more and more. As Harriet Tubman would say, “freedom or death.” And so, in the twenty-first century, those of us who are advocating for a socialist America are fighting an uphill battle, both internally with allies and externally with the capitalist system. But there is, to me, no other alternative. There’s no third way, no middle ground.

About the Authors

Emily Hamilton is assistant professor of the history of science at the University of Massachusetts. Her research focuses on the cultural and political history of mathematics education reform in the United States. She has worked and taught extensively on a wide variety of topics in the history of science, technology, mathematics, and medicine, as well as in oral history methods and philosophy.

Sam Anderson is a Brooklyn, New York, native and a founding member of the Coalition for Public Education and the National Black Education Agenda. He is the author of several books and essays on science, technology, and the history of slavery, among them The Third World Confronts Science and Technology and The Black Holocaust for Beginners. He was an editor at Black Dialog, NOBO Journal, and The Black Activist. He was the first chair of a Black Studies department in 1969–70 at Sarah Lawrence College and taught mathematics, science, and Black history at SUNY Old Westbury, City College of New York, New York University, Rutgers University, and Brooklyn College. He has been active in the civil rights and Black liberation movement since 1964 as a member of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panther Party, and the Black reparations movement. You can find his writing at blackeducator.org.