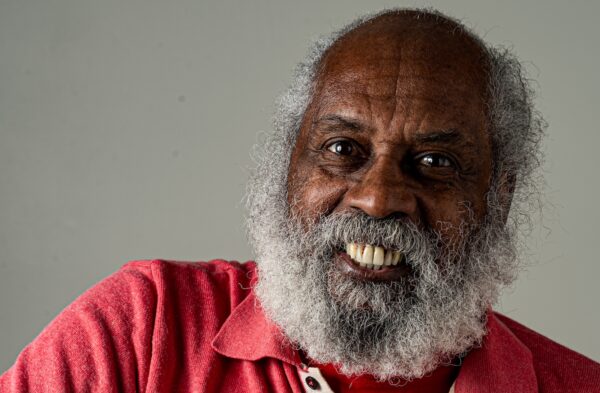

Environmental Crises and Black Liberation: An Interview with Sam Anderson

Part 2

By Emily Hamilton

Volume 23, number 2, People’s Green New Deal

This interview is co-published with Black Perspectives.

Emily Hamilton interviewed Sam Anderson over several days in early December, 2019. Emily is a professor of history and studies mathematics education reform. Sam is an activist, scholar, author, and early member of Science for the People. This interview has been edited for length and clarity. This is a multi-part interview; read part 1 on our website.

Emily Hamilton: The original Science for the People organized around a number of issues in the 1970s and 1980s. Can you describe your particular activism focus within the group?

Sam Anderson: At SUNY [State University of New York], Old Westbury we made sure that once Science for the People started publishing the magazine that our students had availability. It was in the library and some of us purchased a number of copies to use in the classroom. So there was that kind of relationship growing between the faculty members. Even some of the faculty members who were not scientists were also using Science for the People, particularly in the political economy realm. We had discussions around the environmental issues. If the environmental issue is happening in the broader context, what is happening within the Black and Latino communities in and around New York City—these were some of the things that we were beginning to get into.

I was concerned about how we bring students of color into the sciences, and how we could use Science for the People to help bring more students of color into the field of science. Environmental issues were coming into view, if you will, particularly in the Harlem community in the 1970s. We had poor garbage collection in central Harlem and that meant you had these diseases and so forth that were running rampant. We knew that the pollution from the buses was impacting the community—I’m talking roughly 1974-78, about a four-year period. There was a Harlem based environmental group just beginning to form. That was one of the focal points—the diesel buses polluting and the research that group was doing in terms of linkages between respiratory issues and the proximity of these children and adults to the buses, the bus routes, and the bus depot. There was a bus depot—and there still is—on the east side in Harlem, about 127th-128th Street. And there was a large community around it. You had another bus depot on the west side. And so people began to do some research on that, from the community, sometimes with the help of students, Science for the People based students at Columbia University. And so that was one of my concerns, to try to deal with that.

We had an organization—I was living in Harlem at the time—Black New York Action Committee. That was one of the things that we tried to tackle along with the other factor of abandoned housing. There was a study done by Columbia University that mapped illnesses, and the map showed that in many ways a lot of respiratory illnesses or other kinds of environmentally related illnesses were happening in two or three areas in the Harlem community. That was also where we had these abandoned houses and rat infested, garbage strewn, abandoned houses and at the same time, the major north, south, east, and west bus routes. The map was so striking because once you left south of 96th Street on the east side, nothing. No health issues. It’s a matter of two or three blocks. And on the west side, once you left south of 110th Street, downward. Not over by Columbia. Columbia was obviously up on the hill. And that was fairly middle class to relatively wealthy people living in that area. So you didn’t have a health crisis issue [there]. But you come down the hill from Columbia, you see it. You go south of 110th Street and you see that there was no longer a health issue. So that was a very important type of mapping1.

This mapping, this type of research, we were trying to get some people in Science for the People to pick up on. It was done primarily by a group called the Black Topographical Society. And these are young people and what they would do, would be to go into the public records, and look at the developer’s plans. Look at the health records in the New York City public health scene. And what they were talking about and trying to explain to people was not believed until Columbia, a couple of years later, comes out with this report that legitimizes their research. And the whole idea was, not only to expose that reality in Harlem, but the methodology in which they proceeded to do the research can be replicated in every other urban center in the country since they were doing it on public records and then piecing it together with their expertise. One thing I really regret was not being able to get that into one of the issues of Science for the People.

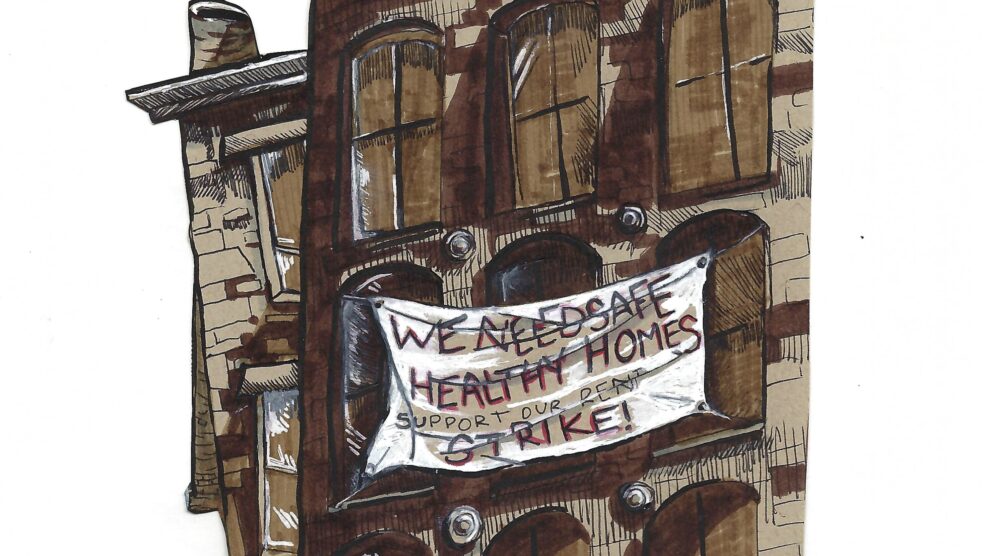

The other thing that was happening in Harlem was the Black Economic Research Center. And that had many types of research. But what overlapped with the work we were doing was their research on housing, or the lack of housing, about landlords sitting on perfectly good housing waiting for the right time to sell and so forth. And the impact that had, as I stated before, with disease carrying rodents, infestation of cockroaches, and what came out of that, was the revelation in the 1980s that there was a direct correlation between cockroach infestation and asthma with young children. Then there was a whole organizing effort. Landlord tenant organizing efforts that went on about getting rid of rats and roaches and so forth. In New York City the housing struggle, the landlord tenant struggle, was fairly formidable. You had some very powerful leaders in that field, in all of the boroughs and particularly in Harlem. Jesse Gray was one of those leaders in this period. He was feared by landlords. He was a great organizer.

EH: Science for the People disbanded in 1989, but of course your activism did not end there. Can you tell us about what kinds of work you did in the intervening years? How did you continue to advocate for public science literacy or organizing in the sciences?

SA: Maurice Bazin and I worked in the mid-seventies on a two-volume book that was published in Portugal and was planned to be published in England, called The Third World Confronts Science and Technology. And it was a collection of work that we had done. Doing the whole historical overview of science: science before Europe, science out of Asia, science out of Africa, science out of the Americas. Then looking at how science was transformed within Europe: during medieval times and how the early stages of capitalism used science to push its economic agenda. And of the direct uses in slavery and the slave trade and how “science” came out of this, how race gets developed as a “scientific development” to rationalize slavery and the slave trade and then rationalize post-slavery, the oppression of people of color worldwide.

Then we talk about contemporary science outside of the US, and outside of the West I should say, in that period during the war, and how the Vietnamese were able to use science and technology to thwart the onslaught of the US military, the various ways they did that. So in a nutshell, what we wanted to do with the book was to show that there is a long history of science and technology that’s not found in Europe and that pre-dates Europe, and that in the contemporary period of the 1970s, is being used by people to fight against capitalist science.

In that period the UN [United Nations] came out with its first major study on the environment, the global environmental crisis. And we talked about that. And what would the earth look like thirty years from now when they were middle aged. That’s now, right! And we talked about that and the dangers and so forth. So the whole idea was to bring in students who would never think about science in any way, shape or form, and see that science, and mathematics, and engineering are part of their lives either directly or indirectly. And that if it’s done wrong, it will be a negative thing down the road. If the capital structure ignores, in 1989 the call of the scientists, or slowly takes it up, we will be impacted thirty years down the road and then their children will be impacted.

EH: Who or what were the most important early influences on your thinking with respect to a political analysis of science, technology, and math?

SA: Some science fiction writers when I was a teenager, you know, Issac Azimov, and a little bit later Ursula LeGuin, and a little bit later in life Octavia Butler were influences. Growing up in the post-World War II 1950s, a lot of the pulp fiction, science fiction, comic books, and novels were around and that helped shape my sense of things about science and led me to be more interested in science.

EH: You’ve adopted the moniker Black Educator. Tell us what education means to you and how it brings together lots of different strands in your political philosophy?

SA: I see myself as covering many different areas under the name of educator, trying to deal with that both in the math-science area as well as in political history, and to a lesser degree now, literature. I used to be a short story writer and poet in the sixties. But so many of us were that anyway. It was like breathing air, you know, in that period, in the explosion of Black cultural material from the early sixties on through the eighties. If you were politically active and you were Black, you were touched by the cultural aspects in one way, shape, or form. And being in New York City, you couldn’t help but step outside, living in Harlem or living in Brooklyn, you step outside and you were in a vibrant Black cultural milieu. This is prior to the gentrification of those communities. And so you incorporated that, you figured out how to weave a lot of that stuff into your own work, your own pedagogical approaches and things.

EH: What do you consider to be the most pressing issues today that Science for the People should be tackling?

SA: The most pressing issues, pick a letter out of the alphabet. There’s so many. I think the unifying issue is the climate crisis. That impacts everybody and it has disproportionate impact in the US on people of color, all over the country. That’s one big issue. And the government right now is not doing anything but the opposite. With the Trump administration, the right wing is going crazy. I just saw a piece where it stated that they don’t have enough agents to go around to inspect in the Food and Drug Administration [FDA].

The climate issue also brings in the importance of science with people being international in scope from its very beginning. Of course, the climate is not just hovering in crises over the United States. There are consequences elsewhere that impact us and vice versa. So I think that the international component needs to be developed in Science for the People. Maybe a conference sponsored by Science for the People, a working conference to develop these international relations and international organizing efforts within Science for the People.

EH: Do you see any potential pitfalls that the new iteration of Science for the People will face?

SA: Yes. I think one pitfall is the Democratic Party. And how once they return to power how they would use the image of being progressive in the area of science and technology to cover their corporate agenda. I think that’s a big danger because the Democratic Party is a reform party. And they will fight tooth and nail any kind of radical disruption of the structures that already exist. The structure of the FDA, for example. They would tweak that, they wouldn’t rethink it. You have to fight tooth and nail in the FDA to get things done that corporations don’t want to happen. And that shouldn’t be. It should be [that] the FDA is getting things done and the corporations should be on the outside. But it’s the other way around.

I mean, there are so many things that have to be addressed in the field of science and technology and government that we have to be very vigilant. The urgency of the environmental issue is one that I think should be front and center to any of the presidential candidates in the Democratic Party. And that requires a radical shift on all levels. It’s like what happened when I was growing up in the 1950s and Sputnik went up before the American satellite. That created a whole radical shift on many levels, particularly in education, to draw young people into the field of science and technology. And a similar thing has to happen but for the [environmental crisis], because that’s a crisis that needs to be recognized and addressed first and foremost.

About the Authors

Emily Hamilton is assistant professor of the history of science at the University of Massachusetts. Her research focuses on the cultural and political history of mathematics education reform in the United States. She has worked and taught extensively on a wide variety of topics in the history of science, technology, mathematics, and medicine, as well as in oral history methods and philosophy.

Sam Anderson is a Brooklyn, New York, native and a founding member of the Coalition for Public Education and the National Black Education Agenda. He is the author of several books and essays on science, technology, and the history of slavery, among them The Third World Confronts Science and Technology and The Black Holocaust for Beginners. He was an editor at Black Dialog, NOBO Journal, and The Black Activist. He was the first chair of a Black Studies department in 1969–70 at Sarah Lawrence College and taught mathematics, science, and Black history at SUNY Old Westbury, City College of New York, New York University, Rutgers University, and Brooklyn College. He has been active in the civil rights and Black liberation movement since 1964 as a member of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panther Party, and the Black reparations movement. You can find his writing at blackeducator.org.

- For a study on similar issues in Philadelphia, see “Rat Control – People’s Science in Philadelphia,” Science for the People 4, no. 6 (November 1972): 20-21.