For a People-Centered Science: A Call to Action

By Shannon Dosemagen

Volume 22, number 2, Envisioning and Enacting the Science We Need

Less than thirty miles south of New Orleans on the west bank of the Mississippi River, LA-23 takes a southern turn through Belle Chasse, winds down past the Phillips 66 Alliance Refinery, to the communities of Ironton, Davant, and Myrtle Grove. The road becomes narrower, and the thin strip of land is bordered on one side by the Mississippi and the other by an intricate series of passageways through the wetlands. The wetlands have been created by a long history of sediment moved by natural processes and industrial dredging which has slowly increased saltwater intrusion.

Years ago, communities in the area began working with national green organizations and local nonprofits to organize against the expansion of a new coal export terminal, United Bulk, on the Mississippi River. Knowing that there would be detrimental effects on both human and ecological health if the project went forward, the coalition began fusing organizing strategies with data, focusing on the potential problems the expanded terminal could cause to wetlands restoration.

Standing on a nearby levee and lofting a camera attached to a kite, members of a newly formed coalition captured the first data point: a single image. This image showed the facility polluting on a “good weather day” (as opposed to bad weather day, where there are certain allowable levels of pollution that a facility can offload). Scott Eustis, who was at the time the Wetland Specialist at Gulf Restoration Network (now Healthy Gulf), called having this data,

a critical turning point in our understanding of the problems with United Bulk’s dock. With the kite, we saw a very close side view for the first time. The pile accumulating beneath the conveyor showed that the conveyor was moving material directly into the river, over multiple days. The accumulation into the form of the pile showed that this was a systemic problem related to their equipment, not some fluke of a shift worker or the wind.1

Because the coalition organized and collected data (from the kite flight and later from additional overflights), they were able to win $75,000 in fines against United Bulk, a halt on coal terminal expansion in the area, and stronger guidelines on containment and cleanup activities. Their success demonstrated the power of using scientific information toward community-identified ends.

Pairing science and data with organizing around local environmental and health concerns is at the heart of “community science.” Community science recognizes that the power of science for communities is not in generating data; it is in using science as a way to move toward social change. In doing so, science is incorporated as one tool among many that people can use in observing, exploring, critically analyzing, and answering questions about the places and communities in which they live.

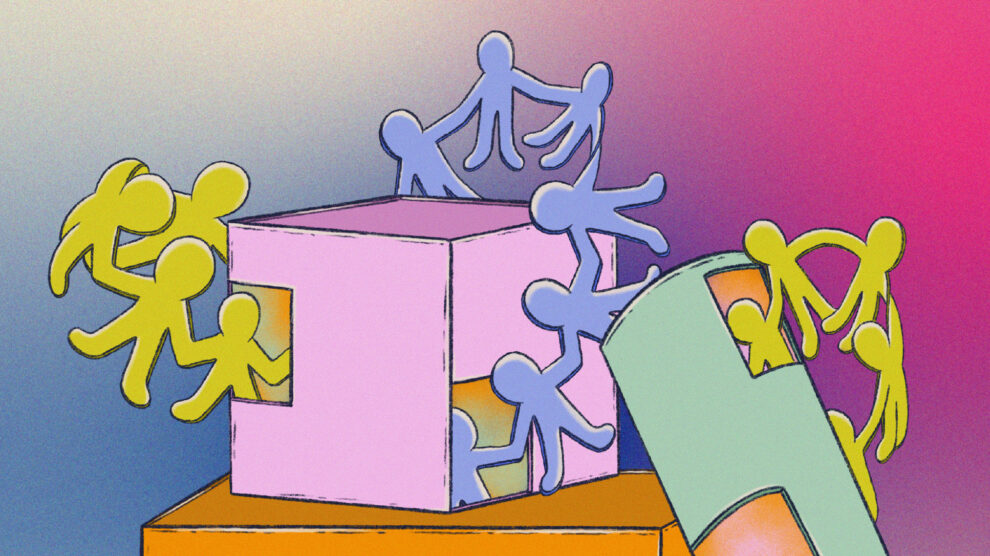

It’s common to see the oversimplification of human complexity and processes in the pursuit of obtaining scientific information. In contrast, community science places deep relationship-building at the center of work. It is part of a broader landscape of the participatory sciences, a term I’m using to describe approaches that include involvement, leadership, and cooperation from the general public. The people-centered approach we take in community science is valuable and should be implemented everywhere science is practiced. This is not a call to do community science, but to collectively embrace and realign our priorities with human relationships over the pursuit of scientific knowledge.

Building A Practice of Community Science

I’ve spent my adult life working with groups and projects that incorporate science and inquiry to create systemic change. My work has spanned from using benthic sampling to raise awareness about invasive species in the Great Lakes to working with refinery communities in the Gulf South. Science can be used for a wide spectrum of activities—bringing awareness of wonder to the everyday, community organizing for change, extending and supporting collective social agency. I’ve engaged at all points along this spectrum, but for this conversation I’m emphasizing that organizing creates change, and that science can help facilitate and bring innovation to organizing in ways that deserve further exploration and consideration.

For the past decade, I have practiced community science with Public Lab. This nonprofit, which supports a global open community, came into existence during the 2010 BP oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico in response to a corporate-controlled media blackout. The activities were organized around a simple premise—that people deserve information, and couldn’t know the impact under the restrictions of the blackout. Collective work used “community satellites” (point-and-shoot cameras attached to giant kites or balloons) to tell the story of how people experienced the disaster through images of areas in the region that people from the Gulf Coast were most concerned about. The reasoning behind this approach was that the resulting data would not be the end-all of our work, but that it would be able to tell a more compelling story that foregrounded the concerns of Gulf residents to the public.

Public Lab’s version of community science emphasizes and insists upon valuing people first and then using and collecting data, if applicable. This framing is about science serving communities rather than communities serving scientific inquiry. Science is used as a tool to support organizing activities. The model of community science stands in contrast to participatory models which interact with people as a means to the predetermined end of obtaining data for science. The way that Public Lab envisioned science and data as able to support change and social agency evolved as a critique of this model.

This is why Public Lab has disputed the use of terms such as citizen science as a label on our work. Definitions of citizen science arose around a similar time from two different fields, but with very different meanings. From social scientists came a definition describing how people could challenge the limitations of science through new forms of activity.2 From ecology, though, rose a definition that has become hegemonic: engagement by the public participating in scientific research that is led by professional researchers.3 In the popularized version, we learned during the BP oil disaster and with our work after, that models of participatory science—such as citizen science and crowdsourcing, where scientists and researchers pose research topics—were typically not focused on or helping to solve community concerns.

Learning from and building upon the frameworks that many before us have created, Public Lab has been instrumental in developing and popularizing community science as a science that stands both in contrast and as complement to citizen science. As more organizations and people become interested in this framing, we’re actively working with partners to better define and outline the principles of this methodology in the hope that more community organizations and scientific networks will adopt these strategies.

In Community Science, Science Isn’t Always the Answer

Science centered on people focuses not on science for the sake of science, but data that are appropriate for the different goals and needs that people have. For example, if the main goal is to start a conversation in a previously divided community on the topic of climate change mitigation, getting people talking first is perhaps a better strategy than starting with “doing” science. The surge of “civic technology” around 2008 to 2010 with an abundance of new digital mapping platforms, open-source software, and hardware tools—and the rise of do-it-yourself (DIY) and do-it-together methodology rapidly expanding the availability of tools to do environmental monitoring—certainly gave a boost to groups hoping to conduct engaged exploration of environmental conditions, but it did not replace the need for robust social organizing as the primary vehicle of change. An illuminating case in point is a fifteen-year ongoing oil leak in the Gulf of Mexico caused by Taylor Energy.4 The Gulf Monitoring Consortium, an incredible group of committed industry watchdogs spent years building a case by collecting data and doing overflights of the site, but without calling for media attention and asserting public pressure in combination with the data collection, the leak would most likely still be capturing little national attention or traction in accelerating clean-up.5

The onset of the industrial era generated new challenges as industry encroached on workplaces and neighborhoods, negatively affecting air and water quality, and polluting residential neighborhoods with contaminants. Numerous groups employed strategies and organizing tactics, such as in the classic cases of Love Canal (New York) and Warren County (North Carolina), to address environmental and health injustices and the burgeoning number of polluted sites in which people were living. Key influencers of the community science methodology of pairing science and data with organizing come from groups that have for decades strategized the use of new tactics to strengthen organizing activities. These include the environmental health and justice movement and groups such as Communities for a Better Environment and the Bucket Brigade model popularized by the now-defunct Global Community Monitor in the 1990s. My previous background, training, and earliest experiences in community science were deeply influenced by the Bucket Brigade organizing strategy. In this model science and data are used to leverage organizing against environmental injustices, extending and augmenting voice and a critical vantage point backed by data to people impacted by industrial petrochemical operations.

Air sampling was only a piece of the Bucket Brigade strategy, even though the model centers on the symbolic technology of a physical bucket that can be used to take air samples. The core work was organizing and connecting social spaces to impacts wrought by the onslaught of industrial facilities. For instance, taking air samples from public spaces—the steps of a church or a school playground—connected the places where community exists in its most social forms to pollution coming from nearby petrochemical refining facilities. As we continue to learn today, air samples from the bucket sampler didn’t always move communities directly from the initial data gathering point to action or justice-driven goals, and it wasn’t necessarily the bucket that was the most critical tool for the job. It was the act of bringing the community together—talking about what people were experiencing, and combining odor logs and years of newspaper clippings to create stark narratives about industrial refining—that would support a movement toward change. The Bucket Brigade taught us that science and the collection or use of data did not always create community-based change, but could help accelerate and drive people toward actionable outcomes. Organizing created a network, knitting community members together through storytelling, relationships, and data that build momentum.

The community science model establishes a methodology that shifts the balance of power in favor of communities. Equipped with a multi-faceted toolset of organizing and facilitation skills and the additional capacity to create richer narratives because of increased access to, and use of, data and information, we can start building toward new paradigms.6 These paradigms will transition the use of science to facilitate and support change from a radical effort to a new normal in the participatory sciences for doing people-centered science.

Change Comes from Organizing, but Science Can Accelerate Transformation

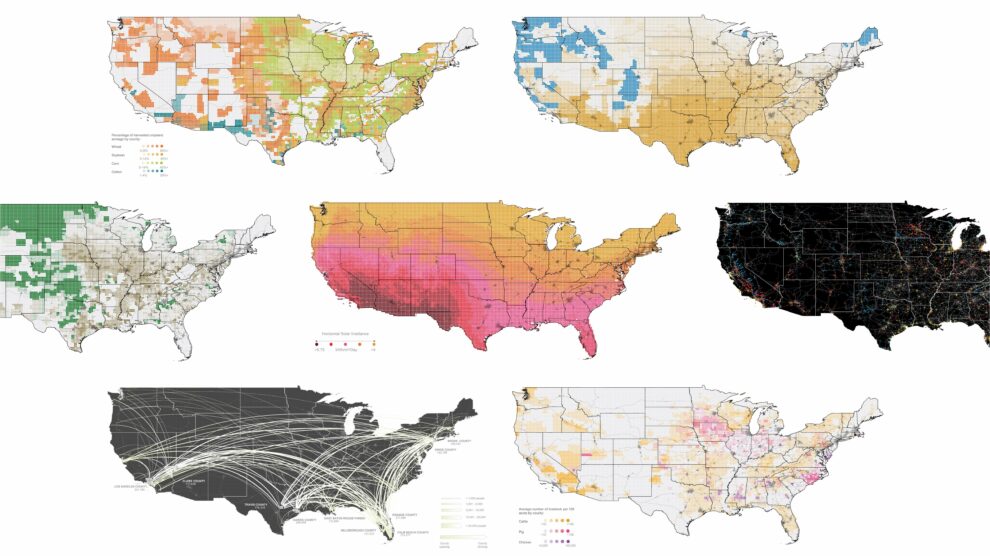

We’ve reached a historical point where the rapidly increasing effects of the climate crisis are now being seen and felt at systemic levels. We need a social departure from the “leave it to the experts” mindset because change isn’t happening fast enough. Being able to use science as a tool for goal-oriented change (through making maps, measuring erosion, understanding the baseline before a new facility comes in) helps society remember how to ask questions, critically engage with information that is presented to us, and leverage our voices as we strive for social change. Science and observation help us understand the passage of time in our unique corners of the world. It is pairing data with observations and visual information. It is understanding how to match and compare new information with old, trying new strategies, and acknowledging what doesn’t work in an attempt to find what does.

We live in a world where the people who are turning political decisions into policy use the language of expertise, data, and science as tools of influence. Comprehensive models of science to support change can help people become part of these decisions. Building on direct, legal, or group action, rallies, and public meetings, we can use science and data as tools to support collective and individual agency. The application of science to support social change exemplifies both broader social and personal impacts:

Redistribute power. Scientific knowledge helps to redistribute power amongst people who may be affected by a given decision. It can help move us toward collective governance, or the ability to participate in governance decisions and structures.

Learn from one another’s strengths. Science can show things in new ways, many times linking the scientific with cultural, political, and deeper community-based narratives. Our understanding of the world is stronger when we can pair different knowledge systems. What is called science is often defined narrowly and precludes other forms of knowledge expressed in a different idiom (such as local, Indigenous knowledge and multigenerational site-based experience). It can provide opportunities for us to learn with each other, across generations and social barriers.

Find new ways to engage people. Science can help us look at problems differently, especially in the way that it moves us through a process of inquiry. It reminds us about the power of observation to question the status quo.

This is a call to embed science as a tactic for organizing and bringing about social change; it isn’t a call for the role and responsibility of government to be taken over by the public. It is, though, an acknowledgement that we live in a world in which industry is allowed to self-monitor. There are deficiencies in our regulatory agencies and limits to their capacity to thoroughly do their job. People must be equipped to be active agents in the conversations, decisions, and changes that are necessary for us to create a healthy society and way of living.

A Call for Action for the Participatory Sciences

There are problems we need to solve in the world of participatory science. We have the potential to vastly amplify the ability for change-focused science to become common, valued, and even part of traditional merit systems. Institutions of science and governance actively create barriers to this. Relationship-building takes longer than funding timelines usually allow. Federal funding requirements for working with “disenfranchised communities” can create uneven, problematic, and exploitative relationships. Researchers are valued for the number of papers they produce rather than how many people they help. People who have been living lives rife with environmental injustices often have solutions. They’ve found a better way forward with ways to unite and be allies and partners.

Scientists, funders, and government agencies need to work toward a resolution, but not in a top-down way. The knowledge and experience to address these structural barriers already exists in social movements for environmental and social justice. Scientific institutions should be listening to people who have worked to identify and call out moments when research creates hierarchical relationships rather than equitable partnerships. Principles for how we can be better partners to each other can be found in the deep social labor people have done to explain the foundational cracks in relationship structures and strategies for fixing them, from the environmental justice movement (e.g., Jemez Principles and Heaney and others’ Community- Owned and Managed Research7) to the problem with labelling people resilient without acknowledgement of the complexities of trauma as one transforms into the “resilient” person (see Eve Tuck’s brilliant letter on “Suspending Damage”8). There are also science networks and institutes that are making strides toward different scientific futures that are not bound and valued only by rapid advancement, but by being better to each other. Examples include the manifesto of the Global Open Science Hardware community, Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research guidelines for maintaining a feminist and anti-colonial lab, and many of the large scientific consortia that are including values and norms in the form of Codes of Conduct for community engagement such as the International Marine Conservation Congress.9

Establishing and putting in the labor needed to build trust-based, human-centered partnerships is far more complex than the data, science, and technology that can be used in support of community goals. This is a problem that must be addressed by a broader social rethinking of science at large. Though the work across participatory sciences takes many different forms, some potentially useful guiding considerations for all our work include:

Explore new perspectives. Recognize that science is political. Science grounded in rigor and integrity can also support change-based action. Envision a transparent and open science and apply it where possible.

Practice facilitation. Together, collectively learn key points of how to facilitate productive discussions and then build this in as part of your practice when you meet. Have ground rules for equitable communication and make sure multiple people have facilitation skills so that gatherings create moments of mutual direction.

Develop a shared vision. Identify the many different points and places where collaboration and expertise can be rebalanced. Recognize the layers of personal experience that we each bring and spend time engaging with aligning values and priorities.

Define processes and expectations. Cocreate values and codes for how to work together. Take care to not co-opt the way that other people work by placing labels or structures they are uncomfortable with on processes they follow. Enact agreements that help to define the distribution of resources and labor, and the ownership of data and products.

Proceed with deliberation. Investment in the social and emotional labor of horizontal relationship-building will lead to deeper ties from which to then organize. Focus on relationship-building, and growing trust by creating strong foundations before getting to what people call “the real work.” Building deep and impactful relationships is one of the hardest things to do and perhaps why so many people shy away from these critical foundations.

There has been an uptick in organizations and institutions building in new policies and initiatives for bringing equity and diversity into the workplace. Problematically, it has at times resulted in organizations that are versed in the language of equity and diversity, but unable to do the deep, systemic work needed to build it into daily practice. Similarly, people-centered, action-oriented work is high stakes and can have harmful effects if done incorrectly. It’s important to understand the capacity that it takes to do truly people-centered work and build in frameworks for accountability.

When Radical Becomes the New Normal

We should all be working toward being better collaborators, recognizing the multiple knowledge systems that exist, and being better allies in structuring relationships in a way that distributes power and lifts up individual social agency.10 Doing this will support us in collectively being equipped to tackle the ever-pressing social, environmental, and political issues of our time. Any new versions of participatory science should support this. Let’s collectively shift our use of science in public spaces from being radical to being the new normal for participatory science.

I write this as a collective call to action. The points outlined here are meant as a starting point on the path toward a future where there is mutual agreement across participatory sciences that fosters structural changes which need to happen. It will be a future where we are bound by a holistic vision of how the scientific world interacts with people. It will see models of science created by the public that are based on mutual agreements for how we collaborate. The labor of relationship-building will be valued. Science and knowledge will distribute power equitably among all people. Our new normal for participatory sciences will be truly people-centered.

Thank you to Dr. Max Liboiron and Dr. Gwen Ottinger for their time spent with me discussing and articulating ideas, and reviewing this article. Thank you to the Public Lab network and partners from which I learn every day.

About the Author

Shannon Dosemagen is co-founder and executive director of Public Lab, one of the originators and organizers of the Gathering for Open Science Hardware, previous Chair of the Citizen Science Association and current Chair of the National Advisory Council on Environmental Policy and Technology. Shannon has spent over fifteen years working with environmental and public health groups to address declining freshwater resources, coastal land loss, and building monitoring programs with communities living adjacent to industry.

References

- Shannon Dosemagen and Gretchen Gehrke, “Civic Technology and Community Science: A New Model for Participation in Environmental Decisions,” Liinc em Revista 13, no. 1 (May 2017): 140- 161.

- Alan Irwin, A Study of People, Expertise and Sustainable Development (London: Routledge, 1995).

- R. Bonney, et al., “Public Participation in Scientific Research: Defining the Field and Assessing Its Potential for Informal Science Education,” Center for Advancement of Informal Science Education (2009).

- As of this writing, the Taylor leak was still active. See Lisa Friedman, “New Estimate for an Oil Leak: A Thousand Times Worse Than Rig Owner Says,” The New York Times, June 25, 2019.

- See Bonny L. Schumaker, “Findings of Taylor Energy and Failures of the US Coast Guard,” On Wings of Care, April 26, 2015.

- In a vast over-simplification of the concept of facilitation, I use this word to indicate the design, implementation and maintenance of ways in which people move through conversations, discussions and decisions in ways that seek common objectives or ways to navigate opposing perspectives on a topic.

- “Jemez Principles for Democratic Organizing,” 1996, EJnet.org, accessed July 20, 2019. Christopher Heaney, et al., “Use of community-owned and -managed research to assess the vulnerability of water and sewer services in marginalized and underserved environmental justice communities.” Journal of Environmental Health 74, no. 1 (2011): 8-17.

- Eve Tuck, “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review 79, no. 3 (Fall 2009): 409-427.

- “GOSH Manifesto,” Gathering for Open Science Hardware, 2016, accessed July 21, 2019; “Methods,” Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research, accessed July 20, 2019; Nathan Bennett, et al., “An Appeal for a Code of Conduct for Marine Conservation,” Marine Policy 81 (July 2017): 411-418.

- Thomas Hervé Mboa Nkoudou, et al., “Towards African and Haitian universities in service to sustainable local development: the contribution of fair open science,” in Contextualizing Openness: Situating Open Science, eds. Leslie Chan, Angela Okune, Becky Hillyer, Denisse Albornoz, and Alejandro Posada (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, in press).