The Imperial Machine Behind the Cholera Epidemic in Yemen

By edna bonhomme

Volume 22, number 2, Envisioning and Enacting the Science We Need

Since the Saudi Arabia-led war against Yemen began in 2015, two million people have been displaced and over ninety thousand have been reported dead as of June 2019.1 The war has also created the conditions for a horrific and sustained cholera outbreak.

Yemeni and non-Yemeni scientists and government officials have analyzed the cholera outbreak on a genetic and public health level, and researchers at the Pasteur Institute surmise that the cholera epidemic in Yemen is related to a broader, global pandemic, associated with the bacterial strain known as 7PET.2 Scientists from the Los Alamos National Laboratory have indicated that the cholera strain in Yemen is particularly virulent and resistant to most antibiotics.3

The morass of details uncovered in these studies about the disease’s genetic traits, bacterial properties, and treatment leave hidden the origins of this illness in war and imperialism. By misconceiving it as an infectious disease pure and simple, these studies focus on the incidental features of cholera rather than the political and social causes germane to its eradication. Once the social and material roots of the illness are taken seriously, the path to eradicating cholera becomes more clear. This is a public health emergency that can only be addressed by focusing on both the infectious bacterial disease aspect of the illness and by bringing the war itself to an end. In the meantime, it is essential to direct resources to rebuilding infrastructure and revitalizing local and community-based medicine.

In Yemen, the cause and trajectory of the recent cholera epidemic cannot be reduced to its genetic characteristics or be solved by foreign humanitarian aid or antibiotics alone. Rather, one must critically examine the social and material conditions conducive to the production and spread of infectious disease. The circumstances that create modern epidemics cannot be extricated from their financial or imperialist roots. Imperialism has a lasting political imprint even when territorial colonialism no longer exists. Yemen has been a laboratory for financial imperialism, steered by foreign capital through high-interest loans at the behest of domestic rulers. Epidemics, such as the current cholera outbreak in Yemen, are a direct consequence of modern-day imperialism that produces new outbreaks and new tragedies. Yemen is a perfect case study for understanding how imperialism makes people sick.

Today, covert imperialism and overt military intervention create the conditions for the cholera epidemic to emerge and flourish. The 2015 Saudi Arabian invasion of Yemen, along with a preexisting poor sanitation system, made it difficult for the Yemeni government or international organizations to manage the outbreak of cholera the following year. The Yemen Data Project has documented that the Saudi Arabia-led war has resulted in over twenty thousand coalition air raids on Yemeni people since 2015, damaging hospitals, roadways, and cultural sites.4 Researchers estimate that by the end of 2019, 133,000 people in Yemen will have died from the conflict and another 233,000 from conflict-related symptoms, including pervasive hunger and ill health.5

Although international organizations and foreign governments have donated millions of dollars to address the cholera epidemic in Yemen, these public health interventions have been unavailing, at times “pitting one approach against another,” as Louise C. Ivers, executive director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Global Health, indicated.6 Shireen Al-Adeimi, Michigan State University Professor of Education, argues, “Saudi Arabia has an interest in maintaining control over Yemen,” which is part of an ongoing imperialist relationship.7 Since 2018, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have donated $145 million (USD) and the United States has given $20 million to the World Health Organization to provide health services to Yemen.8 While these entities profess to reduce cholera’s presence, the United States and Saudi Arabia are directly involved in producing the conditions for disease proliferation through the war. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States governments have distributed funds for public health relief in Yemen, yet they have not taken the decisive step to end the war. Peace and self-governance are prerequisites for the Yemeni people to end the cholera epidemic.

With the end of European colonialism, imperialism is now shaped by international corporations and power players on all continents. Given this dynamic, we must also consider multifarious decolonial strategies in medicine and public health in solidarity with civilians and the victims of war, especially when medical infrastructure is subjected to destruction. Internationally coordinated militarization perpetuates mass death, while humanitarian aid is governed by Saudi Arabia, the US, and other world powers. As it currently stands, international financial regimes and non-governmental organizations, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), produce uneven financial relationships in Yemen—accentuating poverty and illness.

An anticolonial approach to the history of disease can be traced to the mid-twentieth century when Frantz Fanon, author, doctor, and political philosopher, eloquently remarked on the convergence and hierarchy of life and death. He wrote, “With medicine we come to one of the most tragic features of the colonial situation.”9 As a psychiatrist, Fanon was mostly studying the sociodiagnostics of racial tensions between Black and white people, but saw that a similar tension played out in the treatment of the colonized in Algeria. Fanon’s proximity to French colonial violence, his training in medicine, and his participation in Algeria’s struggle for independence gave him singular insights. His position as a medical practitioner within the French colonial regime was the fuel that sparked his anti-colonialism. His analysis of medicine under colonization, developed during the Algerian War of Independence, led him to conclude that Algerians were pathologized under times of war.10

A reading of Fanon and other anti-colonial writers can deepen our understanding of psychiatric illnesses. However, I argue that they can be extended to other diseases, especially in the contemporary context. Understanding the intersection between disease and imperialism today can also help to show how we might begin to rectify the conditions that subject people to epidemics and disasters. At the core of Fanon’s essay, “Medicine and Colonialism,” was a deep meditation on the relationship between medicine and colonialism, in which colonial power could be exercised not just materially and physically over people and objects but also through ideology.11 Studying the causes of disease through the lens of neocolonialism helps us see how disaster and death happen under purportedly humanitarian intervention. Such is the case in Yemen.

Perennial Imperialism

…To appreciate the extent to which Yemen’s story is ‘complicated’ requires moving beyond the geographies, historiographies, and epistemologies used to make Yemen conveniently legible to specialists.12

—Isa Blumi

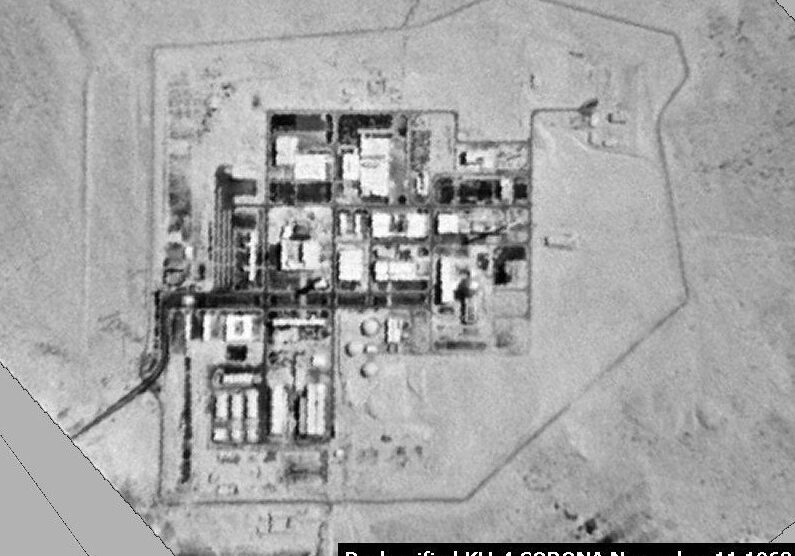

For most of the twentieth century, Yemen was divided into sultanates, with local rulers directing their allegiance to fit their will. As early as 1958, the imamate in northern Yemen looked to the Pan-Arabism of Gamal Abdel Nasser, which eventually led to the formation of the Yemen Arab Republic. In the south, British colonial rule had established Aden as a protectorate in the nineteenth century and functioned as an integral part of Red Sea trade. With armed struggle and a desire to form an Arab socialist state, the People’s Republic of South Yemen, later the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, broke free from British tutelage by 1967. However, the civil war led to political instability and also the forced displacement of Yemeni people.13 Similar to East and West Germany, unification of Yemen occurred shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union in May 1990.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union led to Ali Abdullah Saleh, the then leader of North Yemen, becoming president of the United Republic and Ali Salem al-Beedh, former Secretary General of the Yemeni Social Party, becoming vice president. However, the country could not recover from what preceded during the period of conflict, and poverty contributed to incessant and incremental emigration. Yemen’s pacts with its oil-rich neighbors dictate the extent to which Yemenis may live and work in those countries, with Yemenis often providing cheap labor to Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states.

In 1990, when the United States government proposed its plan to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to invade Iraq, the Republic of Yemen voted against the invasion. The consequences of denouncing the war in Iraq came with a temporary halt in aid and remittances, which crippled the economy. The GCC countries discontinued $500 million (USD) in foreign aid to Yemen.14 As Saudi Arabia is a member of the GCC, 800,000 Yemenis, most of whom had been residing in Saudi Arabia, were expelled from GCC countries.

The government of Yemen became further indebted through privatization programs that it implemented through the World Bank and the IMF. According to Isa Blumi, privatization led the Yemeni government to open up its economy to the free market, which eventually resulted in the liberalization of the “banking, agricultural, and oil sectors.”15 Another dimension was reviving economic investment and collecting revenue from international traders in the port of Aden, which began under President Saleh, by creating partnerships with the International Dubai Seaport Company in 2008.16 Saleh’s financial ventures did not end there.

A mix of corporate and multilateral aid from world powers is inconsistent in its perspective and policies: it creates financial crises in Global South countries while subsequently forming charity-like relationships through humanitarian aid. Multilateral agencies such as the World Bank and the IMF, as Walden Bello has noted in his book, Deglobalization, sidestep democracy by usurping a significant amount of decision-making power.17 In the process of creating uneven financial systems, total war, and aid-dependent societies, new forms of imperialism are created. It is in this vein that decolonial strategies can begin to undo the damage and shock to postcolonial states. As early as the 1990s, Saleh requested loans from the IMF and World Bank as part of a slow process of financial reconfiguration and massive structural adjustment programs. Yet, money was not the only reason Yemen became beholden to foreign interests. A turning point in the Republic of Yemen was September 11, 2001. During that political moment, Saleh acquiesced to supporting the US invasion in Iraq and allowing US Military Special Forces to have a presence in the country. In exchange, he acquired American weaponry, which was used for internal disputes. For example, in August 2009, Saleh launched Operation Scorched Earth, with the help of Saudi Arabia and Jordan, to attack Houthi rebels.18

The military assaults in the early 2000s, alongside economic distress and authoritarian rule, were some of the many reasons leading to the 2010-2011 Arab Spring uprisings. After various protests in Karama Square in the Yemeni capital of Sana’a and throughout the country, President Saleh pledged not to extend his rule. However, his offer was to pass on the presidency to his son, which led to months of protests. By November 2011, President Saleh finally agreed to remove himself from power and hand the affairs to his deputy, Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, which led to a general election won by Hadi. But in 2014, Houthi rebels rose to power in northern Yemen and rejected a draft constitution proposed by the government. By the end of the year, they took control over a significant portion of Sana’a. The Houthis have received funds from Iran, and since Iran and Saudi Arabia are in conflict, this supports the idea that Yemen was a pawn in international relations over which they may have little or no control. At the same time, the Houthis have recently evolved independent of Iranian directives.19

In August 2018, a Saudi-led airstrike (with a US-supplied bomb) hit a school bus, killing fifty-one people, including forty children.20 While the assault targeted rebels, it was innocent civilians who suffered because of the destruction. Fourteen million people—half the population of Yemen—are on the brink of starvation.21

Imperial Cholera

The human cost of the Saudi-led conflict in Yemen today is grave and growing. The war has created conditions of increasing malnutrition and, therefore, compromised immune systems susceptible to infectious disease. War-induced displacement has created an internal refugee crisis, while basic infrastructure, such as sanitation, is being decimated. Collectively, these conditions are ideal for the spread of cholera. Like a prodigious avalanche gaining strength as it rolls down a mountain, cholera is spreading throughout the country and getting out of control.22 Moreover, the pressures of financial deficit and environmental disaster have weakened the very institutions capable of tackling this twenty-first century horror.

The horrific loss of life, widespread malnutrition, displacement, massive destruction of public infrastructure, and the out-of-control cholera epidemic have led to denouncement of the war in Yemen for humanitarian reasons.23 While, in principle, treatment of cholera only demands providing clean water, oral rehydration salts, and gloves, the conditions of war in Yemen are such that these interventions are neither possible nor effective. In 2017, Raslan et al. write in Frontiers in Public Health:

A failing sewage system, continued conflict and inadequate health care facilities are only a few of the reasons contributing to this problem. Malnutrition, which is a significant consequence of the Yemen War, has further contributed to this outbreak.24

A sense of the scale of the crisis can be gleaned from the reports of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), which reports treatment of 103,000 individuals in thirty-seven locations since 2015. Since 2018, they have incorporated seventeen treatment centers with supplies including IV fluids, oral rehydration supplies, antibiotics, chlorine tablets and sent engineers to help restore water distribution across Yemen. However, MSF, like millions of Yemeni people, have also faced direct military attack. Since 2015, Saudi airstrikes have targeted MSF treatment centers, despite receiving the centers’ GPS coordinates in order to be spared.25

In May 2018, MSF launched an oral cholera vaccine campaign in Yemen and attempted to deliver medication to 540,000 Yemenis, though they were only able to distribute the materials to 387,000 people.26 While these efforts have been well received and provided some relief, the outbreak continues. Federspiel and Ali wrote in the BioMed Central Public Health:

Whatever the reasons, OCVs [oral cholera vaccines] were not distributed until nearly 16 months into the cholera outbreak by which time more than a million cases had accumulated … This should serve as a historic example of the failure to control the spread of cholera given the tools that are available.

Non-governmental organizations are not the only ones trying to stem the outbreak. The Yemeni government has also contributed, albeit under the strain of financial restrictions. Over the past few years the Ministry of Public Health and Population in Yemen has struggled to provide adequate services, leading them to partner with the World Health Organization to deliver widespread vaccinations.27 Despite these international efforts, fewer than half of the hospitals in Yemen are operational, suffering shortages of staff and supplies due to the ongoing conflict.28 The thirty thousand doctors, nurses, and other health care workers of Yemen worked for months without pay. These catastrophic conditions are a consequence of this modern-day war, where massive military operations have not only resulted in infrastructure destruction but also the decimation of the body politic.

Unpacking the Theory and Practice of Decolonization

This collective memory of imperialism has been perpetuated through the ways in which knowledge about indigenous people were collected, classified, and then represented in various ways back to the rest, and then through the eyes of the West, back to those who have been colonized.29

—Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies

Yemeni people are subjected to militarized violence— a product of uneven neocolonial power relationships. An underappreciated fact of the cholera epidemic is that the people of Yemen are maligned by a political ideology that attributes the conditions of poverty, illness, and even natural disasters to the failure of the people themselves, rather than recognizing that their roots lie in the structures of neocolonial and imperialist interventions that have either created or aggravated the present-day disaster. While the UN has said that the war in Yemen has caused “the world’s worst humanitarian crisis,” liberal commentators attribute the disaster in Yemen to intra-Yemen disputes, Saudi intervention, and Houthi rebels without breaching more deeply into the role of imperial powers who simultaneously fund and participate in the war and act as humanitarian saviors.30

An Anti-Colonial Perspective

Multilateral agencies with unilateral power, such as the World Health Organization, and foreign governments that have used military force in Yemen, such as the United States, will not solve the humanitarian crisis through charity.31 Instead, it is important that Yemenis gain and exercise political independence as an act of decolonization and remove the power structures that created the catastrophe. This is where political self-determination and anti-colonial perspectives can be useful in generating genuine change. As ideology, decolonization can help to cohere a broader layer of political subjects that are left outside of mainstream politics. In Fanon’s analysis of the struggle against French colonialism in Algeria, he outlined the growing recognition in the liberation movement of the need to include a working class; Algerian representation was required to challenge the military occupation. Scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang offer fresh insight on how to remove modern imperial legacies in their essay, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” stating, “Decolonization brings about the repatriation of Indigenous land and life; it is not a metaphor for other things we want to do to improve our societies and schools.”32 In the case of Yemen, that would mean severing the politically capricious situation where countries such as Saudi Arabia both exercise military force and provide humanitarian aid. We need new options to treat the cholera epidemic today that do not rely on these imperialist powers.

Decolonizing medicine would require reformulating the ways that disease categories get defined, how treatments are enacted, and who is considered a healer. Expanding the categories and actors who are abating disease could also mean incorporating traditional healers from Yemen who could not only serve as bearers of local knowledge but also as medical experts for the region. Outside of Yemen, there are interesting programs that explore horizontal and justice-oriented frameworks for healing, including Dr. Rupa Marya’s “Do No Harm Coalitions,” that believe that health is a human right and strive to incorporate collective social justice in their approach while training a new generation of medical students to think about power and privilege.33 A British collective, Decolonising Contraception, has found ways to destigmatize reproductive health through workshops. These initiatives provide examples of non-judgmental, progressive, and patient-oriented approaches that Yemenis could draw from when rebuilding their medicinal infrastructure.

A harm reduction practice that addresses the cholera epidemic in Yemen might benefit from theoretical frameworks that explore politics from a feminist and materialist perspective. Feminist scholars have argued that horizontal, reflective organizing is a necessary mental framework of decolonial processes. As Sara Ahmed remarks, “Solidarity involves commitment, and work, as well as the recognition that even if we do not have the same feelings, or the same lives, or the same bodies, we do live on common ground.”34 One prime example of solidarity is providing material support, as the sociologist Alondra Nelson reflected, which ranges from reconciliation to reparations.35 Reparations can include targeting institutions, businesses, associations, and governments that have plundered and profited from formerly colonized and enslaved people, and therefore poses questions about where wealth comes from and how to redistribute materials in a democratic fashion. For Yemen, that would mean interrogating its proximity and relationship to the United States, Saudi Arabia, and undemocratic unilateral agencies.

In Yemen, the current social and political order of war deepens the fault line of inequality. A decolonization perspective allows us to understand the health crises in ways that are not narrowly conceived as purely medical. Decolonizing the practice of medicine would require the expansion of methods that give due regard to the politics and history of Yemen. In People’s Science, Ruha Benjamin writes that if one can acknowledge and upend health inequalities, people can begin to have the space and time to be more creative as they move through the world.36 To decolonize medicine in Yemen would mean empowering Yemeni medical practitioners while challenging the imperialist and neoliberal legacies and current practices that influence biomedicine and lie behind the health crisis. The non-governmental organization industrial complex, as perpetuated by the World Health Organization and the UN military forces, are part of the problematic regimes that should be challenged.

Decolonization can help challenge the neocolonial and imperialist interventions in Yemen in material ways; it is not merely a matter of atonement but reimagination, something that was rife during the anti-colonial movements in the mid-twentieth century. As a revolutionary, Fanon offered a praxis for liberation and solidarity in colonial contexts. In a broad sense, he also believed that decolonial practices were not merely about creating new political bureaucracies but incorporating health more fundamentally. Colonialism creates new pathologies, and under conditions of duress, colonized subjects are made sick. It is in this respect that decolonization brings to light new approaches to understanding illnesses and how we might go about curing them.

About the Author

edna is an anti-colonial activist, herstorian, writer, curator, and educator whose work interrogates disease, gender, surveillance, and embodiment. edna earned a PhD in history of science at Princeton University with a dissertation that explored plagued bodies and spaces in North Africa. edna’s work is guided by diasporic futurisms, herbal healing, and bionic beings.

References

- Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project and Yemen Data Project, “Yemen War Death Toll Exceeds 90,000 According to New ACLED Data for 2015,” Yemen Snapshots: 2015-2019, June 18, 2019.

- François-Xavier Weill, Daryl Domman, Elisabeth Njamkepo, Abdullrahman A. Almesbahi, Mona Naji, Samar Saeed Nasher, et al., ”Genomic insights into the 2016–2017 cholera epidemic in Yemen,” Nature 565 (January 2019): 230-233.

- Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, “Mystery of cholera epidemic solved,” Science Daily, January 2, 2019.

- See the Yemen Data Project, yemendataproject.org, last accessed October 18, 2019.

- Jonathan D. Moyer, David Bohl, Taylor Hanna, Brendan R. Mapes, Mickey Rafa, “Assessing the impact of war on development in Yemen,” (Sana’a, Yemen: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2019).

- Louise C. Ivers, “Vaccines plus water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions in the fight against cholera,” The Lancet Global Health 5, no. 4 (April 2017): e395.

- Chris Gelardi, “War Crimes in Our Name: A Q&A With Shireen Al- Adeimi,” The Nation, December 14, 2018.

- “Donations from Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates provide access to health care for millions in Yemen,” World Health Organization, accessed July 31, 2019.

- Frantz Fanon, L’an Cinq De La Révolution Algérienne [A Dying Colonialism] (New York: Grove Press, 1967 [1959]), 121.

- Fanon spends a considerable time in the section on violence discussing the ways that colonialism “dehumanizes the colonized subject” (p. 7) and how the colonialist speaks of the colonized in zoological terms which allude to bodily compartments and diseases. Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth [Damnés de la terre] (New York: Grove Press, 2004 [1961]), 7.

- Frantz Fanon, “Medicine and Colonialism” in A Dying Colonialism, (New York: Grove Press, 1965), 121-145.

- Isa Blumi, Destroying Yemen: What Chaos in Arabia Tells us About the World (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018), 8.

- Fred Halliday, “Catastrophe in Yemen,” Middle East Research and Information Project 139 (March/April 1986).

- Nora Colton,“The Silent Victims: Yemeni Migrants Return Home,” Oxford International Review 3, no. 1 (1991): 23–37.

- Isa Blumi, Destroying Yemen: What Chaos in Arabia Tells us about the World (University of California, 2018), 190.

- Blumi, Destroying Yemen, 178–179.

- Walden Bello, Deglobalization: Ideas for a New World Economy (London: Zed Books, 2002).

- Caryle Murphy, “Analysis: What is behind Saudi’s offensive of Yemen?” Public Radio International, November 2009.

- Vincent Dirac, “Yemen’s Houthis–and why they’re not simply a proxy of Iran,” The Conversation, September 19, 2019.

- Julian Borger, “US supplied bomb that killed 40 children on Yemen school bus,” The Guardian, August 19, 2018.

- “Yemen: Houthis launch drone attacks on Saudi airports, airbase,” Al Jazeera, August 5, 2019.

- Jonathan Kennedy, Andrew Harmer, and David McCoy, “The political determinants of the cholera outbreak in Yemen,” The Lancet Global Health 5, no. 10 (October 2017).

- See: Tawakkol Karman, “Enough is Enough. End the War in Yemen,” Washington Post, November 21, 2018; Jeffrey Feltman, “The Only Way to End the War in Yemen,” Foreign Affairs, November 26, 2018; Martin Griffiths, “The Secret of Yemen’s War? We Can End It,” The New York Times, September 19, 2019.

- Raslan et al., ”Re-Emerging Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in War- Affected Peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean Region—An Update,” Frontiers in Public Health 5 (October 25, 2017): Article 283.

- “Unacceptable investigation findings into Abs health centre bombing,” Médecins Sans Frontières, February 6, 2019, msf.org.

- Frederik Federspiel and Mohammad Ali, “The cholera outbreak in Yemen: lessons learned and way forward,” BMC Public Health 18 (December 4, 2018): Article 1338.

- “Health Crisis in Yemen,” International Committee of the Red Cross, March 6, 2019.

- Shuaib Almosawa, Ben Hubbard, and Troy Griggs, “It’s a Slow Death’: The World’s Humanitarian Crisis,” The New York Times, August 23, 2017; Charbel El Bcheraoui, Aisha O. Jumaan, Michael L. Collison, Farah Daoud, and Ali H. Mokdad, “Health in Yemen: losing ground in war time,” Global Health 14 (April 25, 2018): Article 42.

- Linda Tuhiwai, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 2017), 1-2.

- Krishnadev Calamur, “The Next Disaster in Yemen“ The Atlantic, June 13, 2018.

- See Yemen Financial Tracking 2019, fts.unocha.org/countries/248/recipients/2019.

- Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 no. 1 (2012): 1-40.

- Rupa Marya, “Decolonizing Medicine for Healthcare that Serves All,” Bioneers Conference: Uprising!, Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart, 2017; For information on Do No Harm refer to donoharmcoalition.org

- Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

- Alondra Nelson, The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation After the Genome (Boston: Beacon Press, 2016).

- Ruha Benjamin, People’s Science: Bodies and Rights on the Stem Cell Frontier (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2013).