June 25, 2024

Land Back at Barnhart

Contextualizing the Re-occupation of Barnhart Island in Shared Legacies of Struggle

By Jennifer Lee

Views expressed in this opinion editorial do not represent those of any of the eight individuals arrested at Barnhart Island.

On May 21, 2024, a group of eight Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) community members from Akwesasne were arrested at Niionenhiasekowa:ne (Barnhart Island). Certain individuals among the “Akwesasne 8” had originally gone to Barnhart to exercise their right to build a hunting and gathering shelter on their own territory, in part to protest an ongoing land claim settlement that threatens to hand over Kanien’kehá:ka title to this island, among other traditionally held territories, to New York State. The settlement is being negotiated between New York entities and three Akwesasne government councils.1 Presently, the settlement negotiations would require the extinguishment of Mohawk title to Barnhart Island, which would be effectuated through an act of Congress.2 By asserting their right to the land, the Akwesasne 8 have sent a clear message to both negotiating parties. Barnhart Island, like all other territories illegally stolen and swindled from their community, is not for sale—particularly not by collaborationist band and tribal council entities that purport to represent the full community but that were in fact historically imposed upon it at gunpoint.3

The fact that a group of eight community members was surrounded within just a few hours by approximately 35 police agents (including both border patrol agents and state troopers) is a clear indication of the strategic significance of this island to the interests of settler-capital.4 As Taiewennahawi (Marina Johnson-Zafiris), one of the eight arrestees, explains in her article “Akwesasne and the History of Hydropower,” the Moses-Saunders hydrodam, located at the east end of Barnhart Island, is one of the many dams along the St. Lawrence Seaway that has supplied “cheap” electricity to an unending procession of heavily polluting factories since the 1950s.

For decades, dirty plants like Alcoa, General Motors, and Reynolds Metals harnessed the immense power of the Kaniatarowanenneh (St. Lawrence River) at the Moses-Saunders dam to manufacture aluminum, a cheap, abundant, and malleable building material that requires vast amounts of power to extract and process. Not only was hydropower-fueled aluminum production critical to New York’s economic development, it was central to the national pride and independence of so-called Québec. Eager to assert its autonomy from Anglophone capital in the 1960s, the province began damming rivers on Indigenous land in a frenzy of hydropower nationalism.5

Upstream on the St. Lawrence, the aluminum plants at Akwesasne used a toxic sludge containing polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) as a hydraulic fluid during the production process.6 These PCBs were manufactured by the infamously litigious corporation Monsanto, which continues to evade public accountability for discharging this known carcinogen into the St. Lawrence River and onto Kanien’kehá:ka soil.7 The carcinogenic soup was left exposed on the very grounds where the children of Akwesasne played and where families grew their vegetables. Today, Akwesasne sits downstream and downwind of three heavily polluted superfund sites,8 and residents of Akwesasne report that almost everyone they know has a friend or family member suffering from a rare cancer, metabolic syndrome, or auto-immune disorder.9 Rare, life-threatening illnesses exist at Akwesasne at rates that the public would never consider normal or acceptable in any non-Indigenous community.

Dana-Leigh Thompson, one of the Akwesasne 8, lived about 3,000 feet from the PCB dumpsite of the General Motors (GM) factory for a decade. She calls what is happening to the community nothing short of an “environmental genocide.”

From Turtle Island to Palestine, the struggle at Akwesasne is rooted in the shared struggle of all oppressed peoples of the world who are opposing the illogic of settler-capitalism and the endless violation of the lands and waters that our current economic system necessitates.

As we have seen acutely over the last few months in Gaza, genocides aim to decimate the culture, language, and institutions of a people, by severing the relationship between a people and their land. Waterways like the St. Lawrence River have for millennia served as water well, food pantry, medicine cabinet, library, classroom, transitway, and rec hall of the people of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Like the olive trees and wild akoub of Gaza, the St. Lawrence River is a cultural lifeline to the material practices and traditions that connect one generation of Akwesasronon to the next. To the Kanien’kehá:ka, the hydrodams and the carcinogenic sludge contaminating the lands and waters of Akwesasne represent just another wave of genocide, not different in kind from the wave of residential schools that came before it.

The Moses-Saunders dam in particular remains a strategically important power source for horrifyingly wasteful and deeply illogical capitalist development. A dam-powered, electricity-guzzling Bitcoin mining company called Coinmint currently operates in the heavily polluted shell of the abandoned Reynolds Metals factory—all for the purpose of selling fake digital numbers with no tangible real-world value.10 The absurdity of the situation bears repeating: while Akwesasronon are punished with some of the rarest and most pernicious cancers in the world for eating river-caught fish and garden-grown vegetables, armed state troopers are simultaneously being deployed against them to defend the rapacious hydroelectric consumption of industries like cryptocurrency mining.

What is at stake in the settlement negotiations over Barnhart Island is clear. The recognition of Kanien’kehá:ka sovereignty over the island and surrounding regions would threaten the profits of an ecocidal capitalism that relies on hydroelectric infrastructure to greenwash its endless procession of manufacturing and resource extraction projects. For instance, many Akwesasronon are objecting to the proposed construction of a hydrogen fuel facility by Air Products and Chemicals Inc, which, tellingly, owns the largest industrial gas manufacturer in Israel, and which risks discharging effluent into an already heavily contaminated canal.11 But colonial states have always been glad to spend a few million dollars to quell and appease community resistance, and to develop comprador elements in the form of tribal or band councils that are much easier to control. To New York State, a settlement payout to the tri-council in exchange for title over these lands is a calculated investment that will allow profits to flow unabated from the open veins of Akwesasne.

Faced with the continuation of this environmental genocide, the actions of the Akwesasne 8 must be understood as part of the centuries-long legacy of anti-colonial resistance by the Onkwehonwe, and in the context of broader anti-colonial struggles currently being led by Indigenous peoples around the world. As a new generation of Kanien’kehá:ka youth pick up where their elders left off, the protest cry “generation after generation until total liberation” is as applicable to them as it is to the children of Palestine.

Critical to these parallels is the fact that Kanien’kehá:ka territory has been violently carved up into three colonial jurisdictions—Ontario, Québec, and New York State. Just like the militarized checkpoints of the West Bank, the borders at Akwesasne have long served as a pretext for the daily harassment and violent assault of the Onkwehonwe and other non-white community members, many of whom must pass through the border checkpoints to go to work, see family members, or buy groceries. Kanien’kehá:ka Akwesasronon constitute 70 percent of daily traffic across the “US-Canada” border crossing at the Cornwall Port of Entry,12 and it is not uncommon for border agents to detain individuals or to seize the phones or vehicles of community members without providing an explanation. Paralleling the separation of Gaza from the West Bank through a decades-long process of displacement and settler colonialism, the borders sow unnatural divisions within the Kanien’kehá:ka nation and the governance of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, serving to separate the Kanien’kehá communities of Kahnawá:ke, Tyindenega, Kanehsatà:ke, and Akwesasne from one another, all while making Akwesasne one of the most heavily policed communities on all of Turtle Island.13

Though Akwesasne is not a dense urban center, the harassment of Akwesasronon by armed state and border patrol agents is no different from the daily injustices suffered by Black and Puerto Rican communities in places like New York City. In fact, many of the structural features of their oppression were designed by the very same architects of urban segregation. For one, the eponymous Moses of the “Moses-Saunders power dam” was none other than racist urban planner Robert Moses who infamously bulldozed through poor Black, Latino, and Jewish neighborhoods to build the Cross-Bronx Expressway in Kanon:no (New York City), which residents now call “asthma alley.”14 Like Moses’s segregationist urban freeways, the hydropower dams and militarized borders that run through Akwesasne are physical, concrete manifestations of racial capitalism and environmental racism, designed to weaken, divide, humiliate, and control the community.

These contradictions, once simmering, are now coming to a boil. Just as the urban youth of Tiohtià:ke (Montréal) are beginning to study the cross-cultural histories of anti-capitalist and anti-colonial revolution at the Palestine solidarity encampment at McGill, many of the Kanien’kehá:ka youth of Akwesasne are beginning to reject the authority of colonially-imposed tribal councils, and are instead returning to Kaianerehkó:wa (the traditional governance framework of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy that balances the spiritual and political aspects of life). They are increasingly looking to the teachings of revolutionaries like Karoniaktajeh (Louis Hall) and to their own militant histories of national resistance, to learn how to assert their rights to their land and their culture, and to end the ongoing genocide of their people.

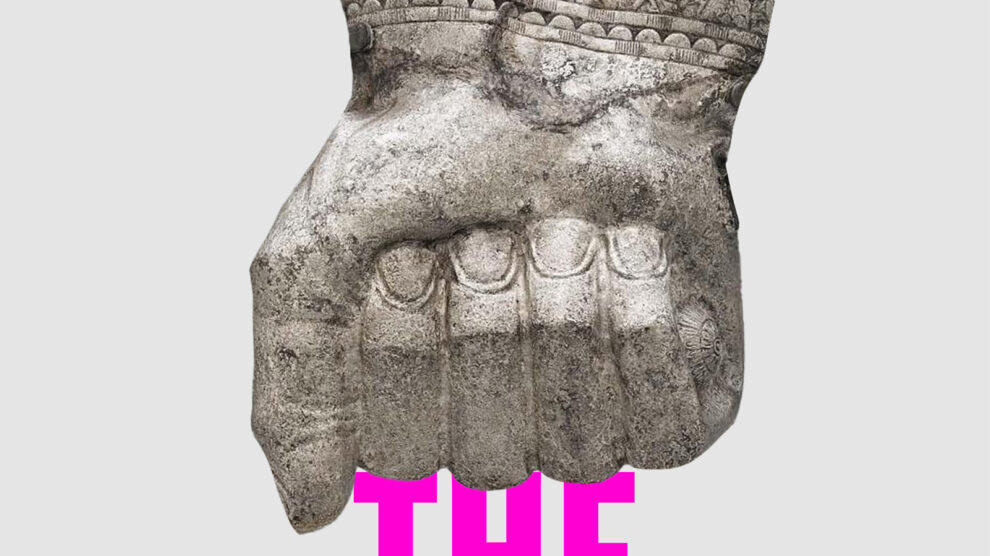

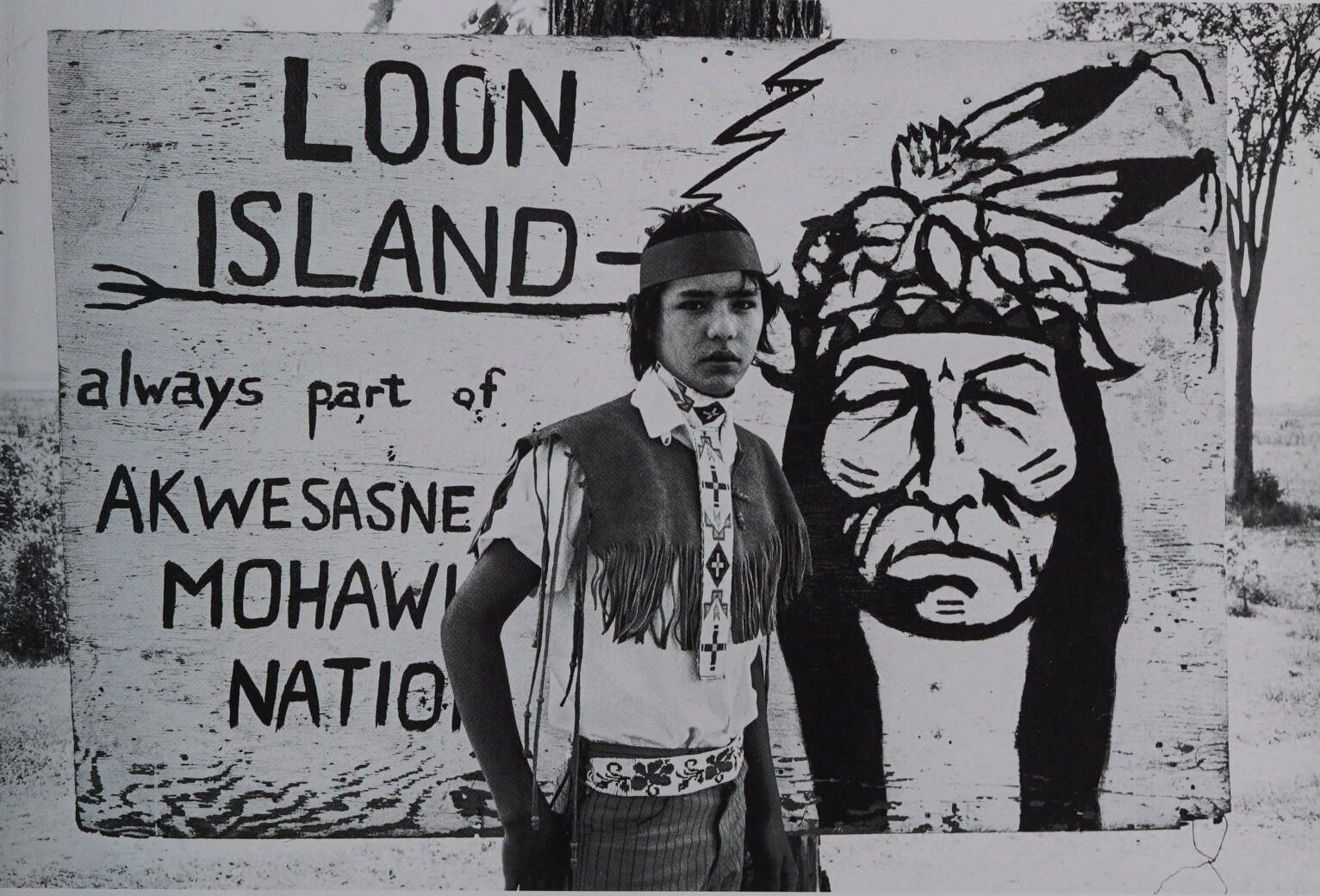

This recent re-occupation of Barnhart Island by the Akwesasronon is part of a long tradition of the Kanien’kehá:ka exercising their rights over the 42 islands of the St. Lawrence River that belong to them. In 1970, a group of Kanien’kehá:ka from Akwesasne landed a barge on Stanley Island to reclaim and reoccupy the island, setting up signs and encampments on the lawns of wealthy homeowners, where they began growing gardens.15 They repeated these actions on Loon Island later that year. The recent actions at Barnhart Island are a continuation of this legacy of radical resistance to genocide through re-occupation.

Certain individuals of the Akwesasne 8 are grounded in rich familial legacies of resistance and are driven to action by the knowledge that it is up to them to protect the land and the unborn children of Akwesasne (“the faces yet to come”).

In 1979, Akwesasne community member Kanasaraken (Loran Thompson) led the resistance to a two-year long siege of his property by state police. Kanasaraken had refused to allow the council to construct a massive fence around the community of Akwesasne, turning construction workers away and confiscating their equipment when they reached his property at Raquette Point. State forces escalated this simple and just refusal into what became a two-year-long armed siege of Thompson’s house, then dubbed Fort Kanasaraken. Thompson, along with dozens of other Akwesasronon supporters, faced off against anti-warrior vigilantes and New York State troopers, who blockaded the roads to his residence to prevent food from coming in. Local supporters were forced to bring food and supplies in by boat.16

It should come as no surprise then that Kanasaraken’s brother Kanietakeron (“Larry Thompson”) was one of the eight arrested last month at Barnhart Island. Having grown up next to GM’s 12-acre PCB dumpsite, Kanietakeron was previously arrested in 2011 for digging up a part of the waste with his backhoe and putting buckets of the toxic sludge onto an outbound train (that was meant to be removing PCBs from the site in the first place). For his clean-up efforts, he was charged with trespassing and arrested on $100,000 bail.17

The people who belong to the land have always historically taken care of it and continue to do so everyday. Jackie Hall, great niece of Louis Hall, is currently facing state (Sûreté du Québec and RCMP) and settler harassment for developing a traditional land back camp and agroforestry project in the western-most portion of so-called Québec, Tsi:karístisere (Dundee). In a practice of both land rematriation and phytoremediation, she is growing a variety of plants such as tobacco, which accumulates heavy metals from the soil, helping to detoxify the land for future generations.18

From the 1974 re-occupation of Ganienkeh (a community currently surrounded by Altona, New York, which is still going strong today), to the 1990 “Oka crisis” (during which warriors fought to protect an ancestral cemetery in the pine groves of Kanehsatà:ke), the current struggle at Akwesasne is rooted in a long and rich legacy of Kanien’kehá:ka resistance to the colonization and violation of their lands and people. The actions of the Akwesasne 8 are grounded in the just national project of rebuilding a Haudenosaunee Confederacy free of the influence of colonially-imposed governance. More than that, from Turtle Island to Palestine, the struggle at Akwesasne is rooted in the shared struggle of all oppressed peoples of the world who are opposing the illogic of settler-capitalism and the endless violation of the lands and waters that our current economic system necessitates.

At the arraignment hearing for the Akwesasne 8 on June 11, the Massena courthouse was overflowing with supporters who had come to show their solidarity. Under public pressure, the courts postponed the arraignments and re-assigned separate court dates to each of the eight arrestees. Apart from the many Indigenous community members who had traveled from far and wide to be there, it is notable that a dozen students from Cornell University who had spent time with Marina Johnson-Zafiris at their campus’s pro-Palestine encampment had driven four hours to the courthouse to support her. It is exactly by recognizing the shared nature and common roots of the struggles of our communities that we can act in solidarity, and win.

—

The arraignment hearings of the Akwesasne 8 have been scheduled for the following dates, at Massena Town Court, 60 Main St #6, Massena, NY 13662. They invite members of allied communities to show their support and solidarity by packing the courthouse on these dates as they reject the jurisdiction of the colonial court outright and refuse to enter a plea for their charges.

June 25th at 1:30 pm – Taiewennahawi (“Marina Johnson-Zafiris”)

July 9th at 1:30 pm – Donald Delormier Jr., Gabe Oaks, Brent Maracle

July 23rd at 1:30 pm – Kahnerahtaro:roks (“Kimberly Terrance”), Dana-Leigh Thompson

August 13th at 1:30 pm – Isaac White

August 27th at 1:30 pm – Kanietakeron (“Larry Thomspon”)

—

Dedication/acknowledgements: This article is dedicated to the brilliant Mohawk Warriors, who center love of life and love of the land in everything they do; to Marina Johnson-Zafiris and Dana-Leigh Thompson, who are inspiring scholars of life, law, and science, and whose knowledge compels them to action; and to Kanietakeron (“Larry Thompson”), Wanda, Sierra, Jackie, Ierahkwí:non (“Tina Square”), and everyone else who shared their stories of love, land, and resistance. Much gratitude to Josh Lalonde and Calvin Wu for their fact-checking and editing work for this article. This article is also dedicated to the for-hire “scientists,” lawyers, federal plants, office bureaucrats, and agents of the state who sold their humanity to companies like Monsanto and Air Products in exchange for an iPhone 10 and a white picket fence—may we one day find a cure for the poison in your minds.

—

Jennifer Lee is a second-generation Chinese-Canadian settler based in Tioh’tià:ke (Montréal), on the unceded territory of the Kanien’kehá:ka. She is studying dialectical biology, neuroscience, and environmental health, and is a big believer in science for the people.

Notes

- David Sommerstein, “New Law Moves Mohawk Land Claim in St. Lawrence, Franklin Counties Ahead,” North County Public Radio, November 28, 2023; The Peoples Voice, “Rights Are Exercised, Not Given – Barnhart Encounter (05-22-24),” May 24, 2024.

- “New York Power Authority Financial Report” (NYPA: New York, 2021), accessed June 25, 2024.

- “Mohawk Councils Respond to Action Taken on Barnhart Island,” Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe, May 22, 2024.

- The Peoples Voice, “Barnhart Encounter (05-22-24),” May 22, 2024.

- The nationalization of hydropower in so-called Québec was a cornerstone of the Quiet Revolution, accomplished by the government of Jean Lesage in 1963. Aluminum, manufactured using hydroelectricity, allowed for the building of all kinds of new, modern architecture, including many of the pavilions proudly on display during Expo ‘67 in Montréal. See also: “Aujourd’hui L’histoire de L’aluminium,” Radio-Canada, March 19, 2024.

- Liz Scheltens, “How US Corporations Poisoned This Indigenous Community,” Vox, August 16, 2022.

- Arthur Neslen, “Monsanto Sold Banned Chemicals for Years despite Known Health Risks, Archives Reveal,” The Guardian, August 10, 2017.

- “St. Lawrence River Area of Concern at Massena/Akwesasne,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, November 13, 2019.

- Bruce E. Johansen, “Akwesasne: Land of the Toxic Turtles,” in Resource Devastation on Native American Lands: Toxic Earth, Poisoned People, ed. Bruce E. Johansen (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023), 17–36.

- Patrick McGeehan, “Bitcoin Miners Flock to New York’s Remote Corners, but Get Chilly Reception,” The New York Times, September 19, 2018.

- Ka’nhehsí:io Deer, “Akwesasne Residents Have Concerns about Proposed Hydrogen Facility in N.Y. State,” CBC News, March 4, 2024; “Oxygen & Argon Works – about Gas Technologies” (Oxygen & Argon Works), accessed June 22, 2024.

- Lindsay Richardson, “New Priority Lane at Cornwall Border Crossing Means Smoother Sailing for Akwesasne Mohawks,” November 4, 2020.

- Tom Blackwell, “Contraband Capital; The Akwesasne Mohawk Reserve Is a Smuggling Conduit, Police Say,” National Post, September 22, 2010.

- Katie Mulkowsky, “How the New York of Robert Moses Shaped My Father’s Health,” November 3, 2023.

- Louis Karoniaktajeh Hall, The Mohawk Warrior Society: A Handbook on Sovereignty and Survival (PM Press, 2023), 242.

- Hall, Mohawk Warrior Society, 60–67, 247.

- Associated Press, “Mohawk Man Charged after Standoff at Ex-GM Site,” Press-Republican, August 12, 2011.

- Katarzyna Kozak and Danuta Maria Antosiewicz, “Tobacco as an Efficient Metal Accumulator,” Biometals: An International Journal on the Role of Metal Ions in Biology, Biochemistry, and Medicine 36, no. 2 (April 2023): 351–70.