March 9, 2024

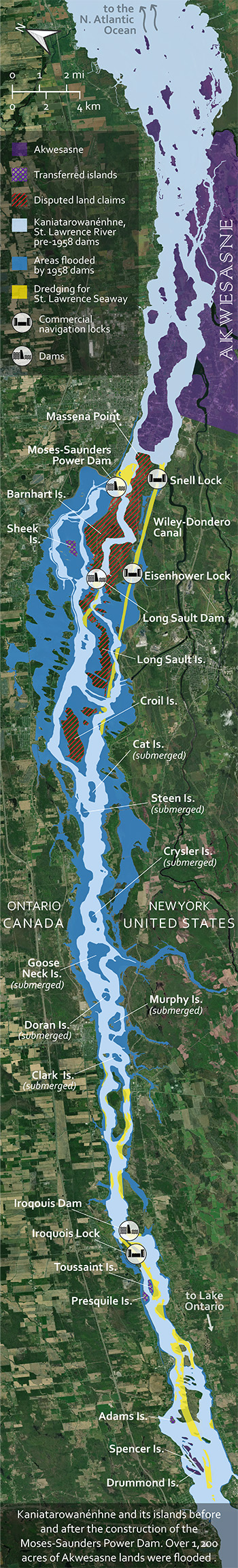

Akwesasne and the History of Hydropower

By Marina Johnson-Zafiris

“[This] is not a story of triumphs of engineering over nature, nor is it a story of masterpiece on international diplomacy, nor even a story about change. It is rather a story about the intimate relationship that the Mohawks of Akwesasne had with the environment in which they lived from time immemorial and how change was forced upon them, through really no choice of their own. It is the story of how the forces of outside government and corporate America seemingly conspired to break the identity of the Mohawk in a manner that no residential school had ever successfully accomplished—by changing the environment in which Mohawk survived . . .” (Elders Study, 1995)

Hydropower has long been heralded as “clean,” “green” energy. Yet living in Akwesasne, just a few kilometers away from the Moses-Saunders Power Dam, it seems that almost every one of its approximately 13,000 residents1 is either sick or has a family member that is sick. And every indication suggests a link to the power dam. How did this happen? When did it begin? And what is being done about it? As a Akwesasne Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) community member and researcher, I wanted to better understand the history of pollution injustice our community has faced, its connection to hydroelectric power and the development of the St. Lawrence Seaway, and the past and ongoing attempts at actionable redress.

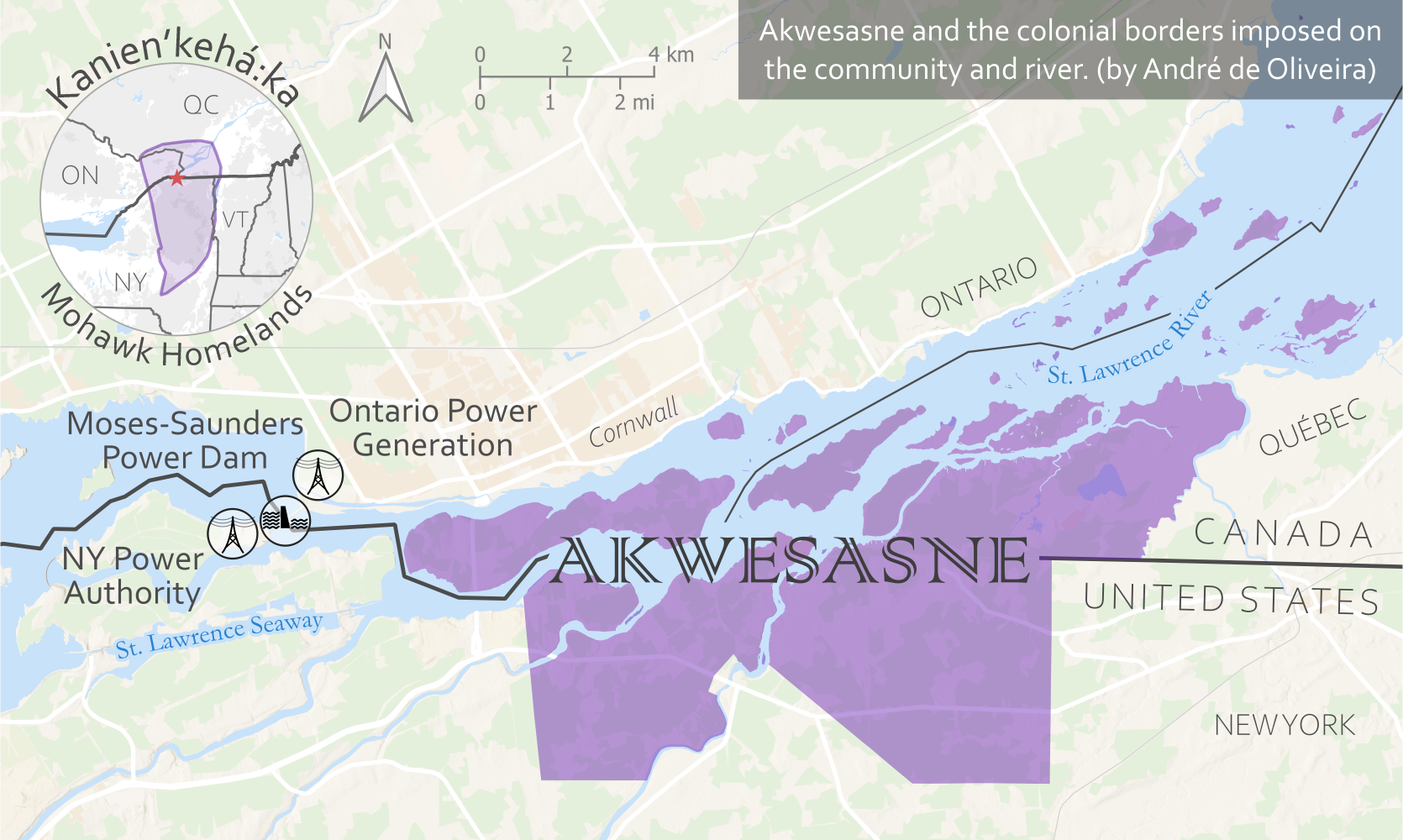

Akwesasne is an Indigenous community whose territory has been imposed on by the three colonial borders of Ontario, Québec, and New York State. The Mohawk Council of Akwesasne (MCA) is an elective governing body for the “Canadian” portion of the community. The St. Regis Mohawk Tribe (SRMT) is an elective governing body for the “American” portion of Akwesasne. Pre-dating the existence of elective systems and these borders, the original governance structure of the Kanien’kehá:ka was laid out by the Kaianere’kó:wa. This original governance system is still practiced, despite all the outside interference it’s faced (see timeline below).

On August 17, 2023, I sat with Brian David, former elected chief of the MCA, to discuss the impact of hydropower on Akwesasne, and to hear about his role in the legal settlement processes that took place in the early 2000s. Over breakfast sandwiches and coffee, we floated down the St. Lawrence, reviewing the decades’ worth of research that went into negotiating the Ontario Power Generation settlement, which sought retribution for the damage done to our community as a result of the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway and the hydroelectric dam.2

“In the early 1900s, there were geologists that were surveying the area. The engineering world at that time recognized the hydro potential of what was called the Long Sault Rapids. This was the only place . . . in the whole entire St. Lawrence River, where there was a drop of like ninety feet. And engineers were studying, ‘Can we capture that?’”

Ontario Hydropower had plans as early as 1913 to harness the energy potential of the Long Sault Rapids by building three large dams, miles of smaller dams, and a system of shipping locks.3 By placing a dam at this juncture of the St. Lawrence river, water flow could be controlled to a level that would allow larger vessels to use open waters to transport goods from the Great Lakes to Montreal. The St. Lawrence Seaway, with its sprawling network of interconnected infrastructure, is now a critical corridor for Canadian and US capital, with 8,000 commercial vessels operating on it each year. Seventy million tonnes of minerals and between 25 and 32 million tonnes of hydrocarbons are transported along the river annually.4

Construction began in August 1954.5 And by 1958, as the St. Lawrence Seaway neared completion, the Moses-Saunders Power Dam was established,6 providing two hydroelectric power generating stations with water: the United States’ St. Lawrence—Franklin D. Roosevelt Power Project (regulated by the New York Power Authority; NYPA)7 and Canada’s R.H. Saunders Generating Station (managed by Ontario Power Generation; OPG).8 Over 1,200 acres of Akwesasne lands were flooded.9

“Chiefs were complaining about Beauharnois dam . . . they had to hold the water back. It raised the water level here, and it flooded the lower islands areas. The Beauharnois dam officials “called up.” And what they offered [the chiefs] as a proposal, as retribution, was something like 5,000 pounds . . . which was a good chunk of change for that time.”

“The chiefs said, ‘you don’t understand what we’re saying. We don’t want the money. The money doesn’t replace the land. We want you to do something so that it doesn’t happen again. It’s harmful to the land, it’s harmful to the water, it’s harmful to our people that survive off the river.’”

The people of Akwesasne were not consulted or compensated in any way for the headpond flooding of our islands.10 The creation of the seaway and subsequently the power dam is one of many waves of genocide our community has faced.

“My father told me about my grandfather—how surveyors came onto his land and started putting pins in, and how he went down and took the pins out; how the RCMP11 came and accosted him and arrested him and took him to Valleyfield. My father told me about his sister, who was pregnant at the time, and how the RCMP took her and threw her into the river. That was my cousin, that was my aunt, that they threw in the river . . .”

“I think part of our job, our mission, is to find out: ‘what were all of the wrongs in the past?’ . . . How is it that they negatively impacted us? What did they do to the people? What did they do to our river? What did they do to our lands? And what did they do to our way of life?”

Not only is Akwesasne’s history of hydropower littered with a trail of violated treaties, but the presence of this infrastructure continues to impact Akwesasne to this day, and will continue to affect Akwesasro:non (residents of Akwesasne) for generations to come. Since its construction, the dam’s cheap hydroelectricity has attracted factory development whose environmental and health effects have disproportionately burdened Akwesasro:non. Industrial pollution from these riverside factories has resulted in decades of chronic disease, illness, and premature death, and has infringed on our right to food and economic sovereignty. The construction of the Seaway has made the people of Akwesasne more dependent upon the Canadian and US government for assistance.12 In addition, the ships that pass through the Seaway act as perpetual conduits for pollution by rapidly introducing invasive species to the region and drastically increasing shoreline erosion.

In 1976, MCA sought retribution for the environmental, health and cultural damages sustained by the Seaway and the dam from the Crown in Right of Canada, the Province of Ontario, Ontario Hydropower, the St. Lawrence Seaway Authority (presently the Seaway Corporation) and other entities in court. This case was dismissed in court due to a technicality: The Crown in Right of Ontario and Ontario Hydro were removed from the proceedings because the Federal Court of Canada does not exercise jurisdiction against the Crown in Right of Ontario. Despite the intimate entanglement of the hydroelectric dam and the construction of the Seaway, the case was ultimately split into two—the 2008 OPG settlement and the Seaway claim, which is still ongoing today.

In 1993, OPG approached MCA to reach a settlement outside of court that would ultimately act as a resolution of all grievances of the Mohawks of Akwesasne resulting from the construction, operation, and maintenance of the R.H. Saunders Generating Station.

“The council looked at me and said: ‘is this [negotiation] something that you can undertake?’ It seemed like a challenge. I thought that we were just going to take the material, go up and negotiate. And then it occurred to me, it’s a little more complicated than that… I said, you know what? I think it’s necessary for us to go out and talk to those old people because that’s why we’re involved in this. It’s not for us. It’s for them. Because something happened that impacted their lives that they had to take to their graves. Let’s go out and talk to whoever we can before they pass away, to collect that information, because that’s why we’re at the table. That’s the substance of what we need to negotiate. And that gave birth to the Elder Study.”

Consisting of 105 interviews over two years (1993–1995), the Elder Study was created to document information during “the Seaway Years” from the perspective of community members. It touched on a variety of themes about the community’s lifestyle (fishing, trapping, farming), and captured unique stories and accounts of historical events.

From all accounts, it can be said that the people were living independently. The primary language of the territory was Onkwehonwenéha, with a small number of bilingual speakers that also spoke English. The economic system that was in place in the community at the time was predominantly a barter system.

“There are many Mohawks who view the river system as being their “life-cord” of sorts. [Before the Seaway was built], there is no word in the Mohawk language for pollution—the river system is healthy, the air is healthy, the land and vegetation are healthy and the people are healthy . . .” (Elders Study, 1995)

My generation has grown up used to fishing advisories, murky waters and no-swim zones. The interviews paint the picture of an Akwesasne that now seems so distant. Elders talk about being able to see the bottom of the river from at least twenty feet above. The river was the main source of drinking water for the community. Fishermen would often catch sturgeon, individually weighing in at over a hundred pound. Weed beds surrounding the islands were rich with traditional medicines.

And then came the construction.

“[The oral accounts go] right to the dynamiting that occurred, the dredging of the river itself and how people felt about that. There are instances where people broke down and we had to stop the interview because it hurt so much. We knew that was going to happen, and we would stop, just as if they were our parents, to say, ‘look, do you need a few minutes? Do you want us to stop and come back? Is there something that we can do?’ And they would usually say, ‘there’s nothing you can do to ease the pain.’ Those are the people that we’re negotiating for. Not me. Not the [settlement] team, and the team understood that. They are the ones that were robbed.”

Elders had the choice of detailing their accounts in either Onkwehonwenéha and/or English (most were conducted in Onkwehonwenéha, some even in an “old dialect” containing words and phrases that are no longer in use). The details were compiled in a report consisting of a synthesis of the interviews as well as direct quotes and unique stories from the transcripts. This material was then utilized as leverage for negotiating settlement terms with OPG. It now serves as a priceless archive of the words of our elders and the stories of what they witnessed and experienced.

“We went back to part of those interviews. We went back to the people. We say, well, what will satisfy? We know we can’t have what was, but… can we talk about what might address it?”

“We have to do something about our children. They’re going to school, yes. We put them in school, yes. But we don’t want to lose them in school. We want to have some means of instilling their way of thinking. Onkwehonwe.. They don’t lose that. Because if they do, then they’re lost . . .”

“We want you to negotiate in a manner that provides a better life for Akwesasro:non. But more so, to provide a sense of certainty for our grandchildren and great grandchildren to come.”

“Fifteen years I spent on [the negotiations]. Probably, in a way, the most influential 15 years of my life. The toughest 15 years, but the most meaningful. It made me understand who I am and why I’m here. What I was fighting for. I didn’t mind the fight at all . . .”

In October 2008, a final agreement had been signed by OPG representatives and the elected grand chief of MCA. The outcome of the settlement was:

- A certified apology from OPG (section 4 of Final Settlement agreement).

- C$45,000,000 compensation to MCA (section 5).

- A “Transfer of Islands” including Adams, Toussaint, Presquile and Sheek as well as islands that had been flooded, which placed these lands under MCA jurisdictional authority (section 6).

- The establishment by OPG of a process to work with MCA to explore mutually beneficial environmental stewardship (section 8).

- Active recruitment of career-oriented students to work for OPG (section 9).

There was an attempt at including power allocation to the negotiations, but OPG refused to include electrical supply as a provision. In exchange, MCA released OPG of all the past, present and continuing impacts, damages and losses. These damages and losses include (section 3.2):

- The disturbance of the natural flow of the St. Lawrence River

- Impacts on the traditional way of life including fishing, hunting, trapping and harvesting

- Impacts on the resources

- Impacts on self-sufficiency

- Impacts on the education system and loss of traditional knowledge

- Impacts on the cultural pride and the self-esteem

- Impacts on sites of cultural significance including burial sites

- Deterioration of the landscape

- Erosion

In addition, the MCA acknowledged that OPG will continue its operations and maintain its existing facilities in the Traditional Territory and accept the Facilities and Operations for as long as OPG desires (section 7.1).

The MCA was offered C$45 million in compensation. The same year OPG produced C$6 billion in revenue.13 The settlement funds were placed into Mohawks of Akwesasne Community Settlement Trust, which now funds various community projects and organizations.

“Ultimately I’m going to have to come back [to the community] with a settlement to say: ‘This is what we got for this. Is it okay?’”

I asked Brian how he would answer his own question, fifteen years after the settlement regarding the hydroelectric dam. Has the money and the apology addressed the harm?

“The short answer…? No. It never can.”

A few days after our discussion about the OPG settlement, on August 23, 2023, the people of Akwesasne voiced their stance in the second set of damages: the ongoing Seaway Claim. This would have finalized the outstanding claims MCA has put forth for damages caused by the Seaway itself. It would have consisted of (yet another) C$45 million payment made to MCA. In exchange, the settlement would relinquish the right of all Akwesasro:non (including that of generations to come) to seek retribution for past, present and future erosion. Of the approximately 7,000 eligible to vote in the referendum, 170 voted in favor of the settlement and 275 voted against.

The no-vote is perhaps a reflection of a lack of agreement on how much our community deserves in compensation for the loss of lands, waters, way of life, and people. Some argue that Akwesasne deserves retribution beyond monetary compensation, as stated before by the chiefs in the 1950s, who were quick to remind dam officials that money cannot replace the land: “We want you to do something so that it doesn’t happen again.” The Seaway Claim litigation now goes back to the drawing board.

On the “US-half” of the dam, there has yet to be any litigation addressing NYPA’s electric subsidization of environmental genocide and its hand in pollution-induced deaths. However, NYPA is an active party in an ongoing land claim settlement with the tri-council due to its contentious occupation of Indian lands, specifically Barnhart Island (where NYPA hydro-power facilities are located).14 To quell concern that their hydropower facilities are squatter infrastructure, NYPA is offering the tri-council US$70 million and nine megawatts of subsidized power.15 In exchange, NYPA and New York state are requiring congressional legislation to dismiss the Mohawk claim to the disputed lands, including Barnhart Island.

Curiously, this land claim settlement is being finalized in the midst of mass energy transitions. While New York seeks to move away from fossil fuel dependency, hydroelectric power is seen as a more “attractive” alternative.16 We are already actively witnessing new industries setting up shop near Akwesasne to collect the benefits of subsidized “green” energy—the most recent case being a proposed US$500 million facility that plans to convert over 2.5 million gallons of freshwater per day into liquid hydrogen fuel, to be transported and sold elsewhere.17

Despite having faced the disastrous impacts of proximity to hydropower, Akwesasro:non do not benefit from the dam’s supply of “cheap” energy. Our electric grid within Akwesasne is split up into three parts—New York State Power, Ontario, and Quebec. Hydro-Quebec routinely falls short.18 Blackouts are all but guaranteed to occur every winter, impacting families trying to stay warm and elders who rely on life-saving equipment such as oxygen tanks. Meanwhile, industries get to operate at high power capacity with low rates; a cryptocurrency mining facility just outside of the community (North Country Data Center) gets to operate 24/7 on lowest-priced wholesale power, courtesy of the hydroelectric dam and subsidies.19

In the midst of these multi-generational battles for various forms of retribution, a few questions become salient: are US and Canadian courts a viable mechanism for redress? Is the band council or the tribal council capable of fully arguing for litigation regarding Kanien’kehá:ka liberty and independence when the councils are effectively extensions of the Canadian and US governments? Is the community ready to move beyond a framework of negotiation limited to fixed monetary amounts and land reallocation, in recognition of the fact that we already have inherent rights to the land? For decades, the river’s power has been used against the people of Akwesasne, and we continue to bear the cumulative health effects of decades of environmental degradation, industrial pollution, and chronic toxicant exposure. One thing is certain: if the river is our life-cord, we cannot rest until she does. ♦

This article will also appear in the upcoming SftP magazine print issue, “Ways of Knowing.” This is the first in a series dedicated to storying the complex environmental and socio-political entanglements of pollution injustice in Akwesasne—past, present and future.

·

St. Lawrence Seaway Archive Photos (click to enlarge):

·

Acknowledgements: This article would not have been possible without the incredible work of Brian David and the rest of the Elder Study research team. Much gratitude to the article editors Jenn Lee and Calvin Wu for the incredible support and to SftP for hosting and printing this work. Nia:wen to the archivists and librarians of the Akwesasne community at the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne Archives and Akwesasne Cultural Center Library. This writing along with the rest of this series is dedicated to the Á:se Tahatikonhsontánkie’ (the Faces Yet to Come)—may we leave the water, lands and air better for your arrival.

—

Marina Johnson-Zafiris is a PhD Student at Cornell University in Information Science, with a minor in American Indian and Indigenous studies. Her research interests focus on 1) computational community science and technological interventions for industrial accountability and socio-environmental justice and 2) critical data/information studies across Haudenosaunee Territory. Marina is Kanien’kehá:ka (Wolf Clan) on her mother’s side and Greek on her father’s side. She is presently based both in Ithaca, New York and Akwesasne.

André Luiz de Oliveira Domingues is a masters student of GIS at Clark University. He is from Brazil and grew up in New York. Prior to graduate school, he worked as a farmworker in New York’s Hudson Valley and southern Arizona for ten years. André is interested in mapping as a tool for spatial analysis and liberation. He is currently based in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Map data sources:

- St. Lawrence river related shapefiles by Jamie Ferguson (“A Visual History of the Project”, 2023)

- Kanien’kehá:ka Territorial Homelands JSON file by Native Land Digital (“Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk)”, 2022)

- Border shapefile by Government of Canada (“Administrative Boundaries in Canada – CanVec Series – Administrative Features”, 2019)

- Basemaps by © MapTiler & © OpenStreetMap contributors

Notes:

- “Akwesasne History,” accessed February 26, 2024.

- Ontario Power Generation (OPG) settlement, accessed March 8, 2024.

- The predecessor body of OPG was originally called the Hydro-electric Power Commission of Ontario. Its name was changed to Ontario Hydro. Around 1998, it was “privatized” and renamed as Ontario Power Generation. See also: Arthur V. White and Canada Commission of Conservation C, Long Sault Rapids, St. Lawrence River: An Enquiry Into the Constitutional and Other Aspects of the Project to Develop Power Therefrom (Creative Media Partners, LLC, 2021).

- Claude Comtois, “How the St. Lawrence Seaway Will Continue to Become More Important to the Economy,” The Conversation, August 3, 2022.

- Gordon C. Shaw and Viktor Kaczkowski, “St. Lawrence Seaway,” accessed February 26, 2024.

- Jamie Ferguson, “A Visual History of the Project,” Esri, December 14, 2022.

- “St Lawrence Power Project,” accessed February 26, 2024.

- “Our Story,” OPG, July 6, 2023.

- OPG settlement, accessed March 8, 2024.

- It is important to note that the Seaway presented the project to the St. Regis Band Council (presently the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne). The Indian Agent headed the negotiation and a number of islands were specifically identified that would be flooded by the headpond. The Band Council at the time privately negotiated compensation for these islands which was duly paid and purported to “approve” the taking of the islands by resolution.

- Colloquially used in its abbreviation for Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

- Elders Study, accessed March 8, 2024.

- “Financial Summary,” OPG archive, accessed February 26, 2024.

- The tri-council consists of the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe (US governing body), Mohawk Council of Akwesasne (Canadian governing body), and the Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs (a traditional governing body).

- A squatter is typically defined as an entity that “unlawfully occupies an uninhabited building or unused land.” I utilize the term squatter here to emphasize the illegitimacy of NYPA’s holding on Barnhart Island. There is both oral history and written documentation that supports Kanien’kehá:ka presence and stewardship of Barnhart.

- “New York’s Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act – New York’s Climate Leadership & Community Protection Act,” NYSERDA, accessed February 26, 2024.

- “Public Participation Plan,” C&S Company, accessed February 26, 2024.

- Shawna O’Neill, “Akwesasne Communities without Power for over 36 Hours,” Cornwall Standard-Freeholder, January 6, 2023.

- Patrick McGeehan, “Bitcoin Miners Flock to New York’s Remote Corners, but Get Chilly Reception,” New York Times, September 19, 2018.