Ciencia Digna: The Latin American Movement for a “Pueblo-centric” Science

By Ingrid Elísabet Feeney

Volume 22, number 1, The Return of Radical Science

Introduction

It was early morning and the summer sun was just beginning to burn through the blanket of dewdrops which bathed unruly clumps of grass and earth in luxurious cascades of crystal. In the distance, the sound of a tractor engine firing up punctured the stillness of the lingering mist.

A group of about thirty people had gathered in a patchy, overgrown field in the shadow of a sprawling, weatherworn brick and concrete building—the Athletic Club of Barrio Ignacio Suárez in the outskirts of the capital city of the Córdoba province in Argentina1. Some in street clothes, some in hospital scrubs, they milled around in clusters, passing gourds of steaming mate, chattering, and fiddling with their smartphones.

I felt a hand on my shoulder. “Here you go,” Cristina said, passing me a lanyard and badge with my name and passport number printed under the heading Institute of Socio-Environmental Technology. “It provides a veneer of institutional legitimacy,” she explained, her brown eyes crinkling with an arresting mix of good humor and dead seriousness. “But don’t get it twisted,” she added, raising an eyebrow for emphasis. “This is pure militancy.”

It was December 2018 and, in anticipation of an upcoming trial, the Institute of Socio-Environmental Technology had gathered a team of volunteers for the first day of work on an epidemiological survey of the notoriously contaminated Barrio Ignacio Suárez. Ignacio Suárez is flanked by vast fields of transgenic soy. Residents report a cancer rate forty-one times the national average as well as high rates of neurological and respiratory diseases, thyroid conditions, birth defects, and infant mortality. Over 80 percent of local children have multiple agrichemicals in their blood.2

The Institute of Socio-Environmental Technology (ITSA) describes its mission and work as “critical community epidemiology;” it shares a headquarters with a murga performing arts group and various arts and media collectives in a cooperatively managed space in the capital city of Córdoba known as Casa Revolución.3 Cristina Arnulphi, a retired biophysicist, coordinates medical students and doctors, biologists and geographers, programmers, sociologists, lawyers, agricultural engineers, and other STEM professionals to systematically survey communities in the rural interior of the Córdoba province, where steadily increasing levels of agrichemical application since the introduction of genetically modified crops in the mid-1990s have been accompanied by emerging epidemics of chronic illness. A doctoral student in cultural anthropology, I’ve been working with ITSA to bring some ethnographic “thickness” to the data points being generated by the survey instrument.

Córdoba-based ITSA, Salud Socioambiental (Socio-Environmental Health) in Rosario, and Gesta Colectiva (Collective Feat) in Buenos Aires together form the Grupo Epidemiológico de la Ciencia Digna—the Epidemiology Group of Dignified Science.

The group is one branch of the Unión de Científicos Comprometidos con la Sociedad y la Naturaleza—the Union of Scientists Committed to Society and Nature—which operates in Argentina, Mexico, Ecuador, Costa Rica, and Brazil. Since 2014, in the context of mounting socioecological catastrophe propelled by the rapid expansion of agribusiness and other forms of neoliberal extractivism in Latin America, this network has been mobilizing scientific knowledge in the service of socioenvironmental justice struggles under the banner of Ciencia Digna, or Dignified Science.

The Latin American Declaration for a Dignified Science was written by the late microbiologist, Andrés Carrasco, who sacrificed his career to publish a seminal paper on the health impacts of glyphosate.4 The declaration focuses on the social, environmental, and philosophical consequences of an extractivist agricultural model centered on genetically modified crops, the role of corporate science in perpetuating the model, and the need for a “committed,” “pueblo-centric” science to take it down.

Ciencia Digna takes its name from the concept of vida digna (dignified life): a life in which one’s basic needs are met, which has been the aim of many Latin American social movements. Because Ciencia Digna roots its priorities in the right of the pueblo [community] to a dignified life, rather than in the imperatives of the market, it is “pueblo-centric.”

The “Soyification” of Argentina

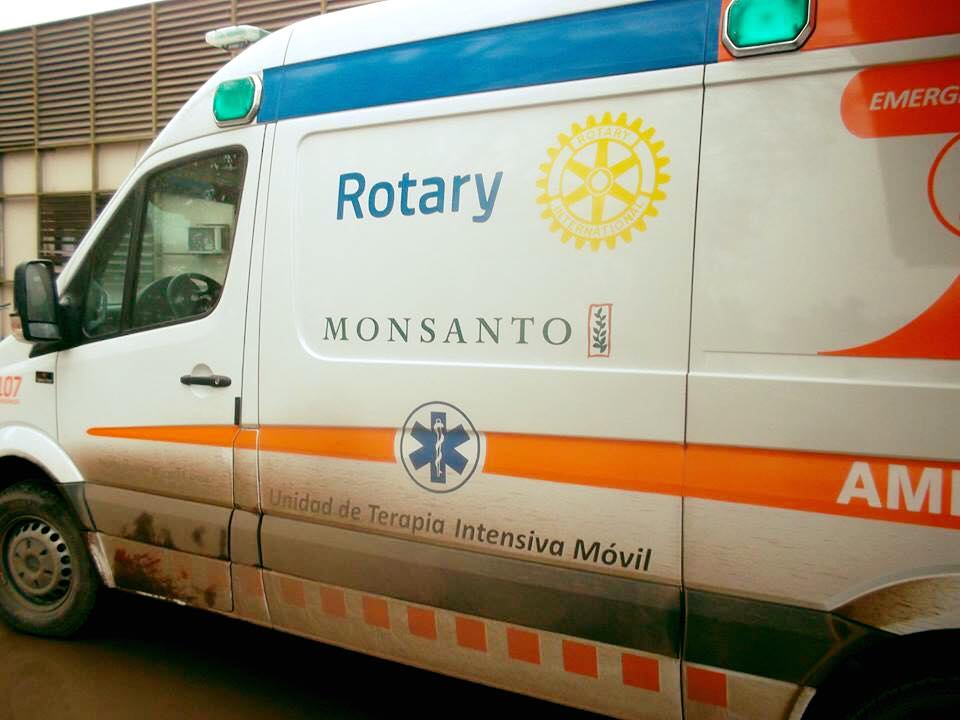

Roundup Ready soy, legally introduced to the Argentine market in 1996, was one of the first commercially successful genetically modified (hereafter GM) crops. Engineered by the American agribusiness firm Monsanto (recently purchased by the German chemical-pharmaceutical corporation Bayer), Roundup Ready soy is genetically modified to withstand application of the herbicide Roundup.

Roundup is the trademarked name of Monsanto’s flagship glyphosate-based herbicide, now off-patent and sold by other companies as well. Today, over 90 percent of GM crops cultivated worldwide are engineered to be resistant to glyphosate, and global agricultural use of the herbicide has risen about fifteen-fold, from 51 million kg applied in 1995 to 747 million kg applied in 2014.5 It is by far the most widely used agrichemical today and in the history of agriculture.6

Argentina has been particularly affected by the issue of increased glyphosate use. Historically, Argentina produced a diverse array of agricultural products such as beef, dairy, wheat, corn, sunflowers, rice, potatoes, and wine. However, in the last twenty-five years, Argentina’s agricultural landscape has been dramatically transformed by the widespread adoption of GM soy, facilitated by the neoliberal restructuring of the Argentine economy under the administration of President Carlos Menem and extended under the “post-neoliberal” Kirchner years.7 Locally this process is known as sojización or “soyification.”

While soya expansion in the region is promoted by powerful actors as a “green” way of encouraging rural development and energy independence, and the technology has been appealing to many growers because of its simplicity of use, the soyification development model has eroded food sovereignty and generated environmental crises such as deforestation, leaching, erosion, soil and water degradation, and chronic flooding.8 The transnational peasant movement La Via Campesina estimates that since 1996 the advancement of the soy frontier has forced around 200,000 rural families (over 900,000 people) off their land and into metastasizing slums on the periphery of major cities such as Buenos Aires.9 Today, more than half of all arable land in Argentina is planted with transgenic soy.10 The soy frontier is currently pushing further and further into the lowland forest region of the Gran Chaco, which together with the Amazon has long been known as one of the two “Lungs of the Americas.”

The GM soy boom has produced an array of grave socioecological problems in Argentina, but perhaps none has been so devastating as agrochemical contamination. In 1996, the year transgenics were legally introduced, 39 million kg of glyphosate were applied within Argentina’s borders. By 2015, this figure had surpassed 360 million kg, a more than nine-fold increase in under 20 years.11 Today, with 7.6 kilograms of glyphosate alone applied per person per year, Argentina has the world’s highest level of per capita agrichemical application.12 In the rural interior of the Pampas, where the toxic load is particularly heavy, the level reaches 79 kg per person per year.13

Skyrocketing rates of agrochemical application in the region have been accompanied by a marked shift in the epidemiological profile of rural Argentine populations. In some soy-growing regions, one out of every two deaths is now attributed to cancer.14 The rates of congenital birth defects and spontaneous abortion are particularly high in the fumigated rural interior, with an alarming 25 percent of pregnancies lost in some communities.15 Recent studies have revealed the devastating extent of contamination of rainwater, rivers, and soils in the region.16 In 2018, a mass die-off of condors, along with the death of 72 million bees in the soy-growing province of Córdoba,elevated civil unrest against the agro-export model to fever pitch.17 Extreme soil degradation, deforestation, and climatic instability have converged in the sudden emergence of a rift twenty-five km long, sixty meters wide, and twenty-five meters deep in Argentina’s agricultural heartland, a dramatic new landscape feature called the Río Nuevo, which opened virtually “overnight.”18

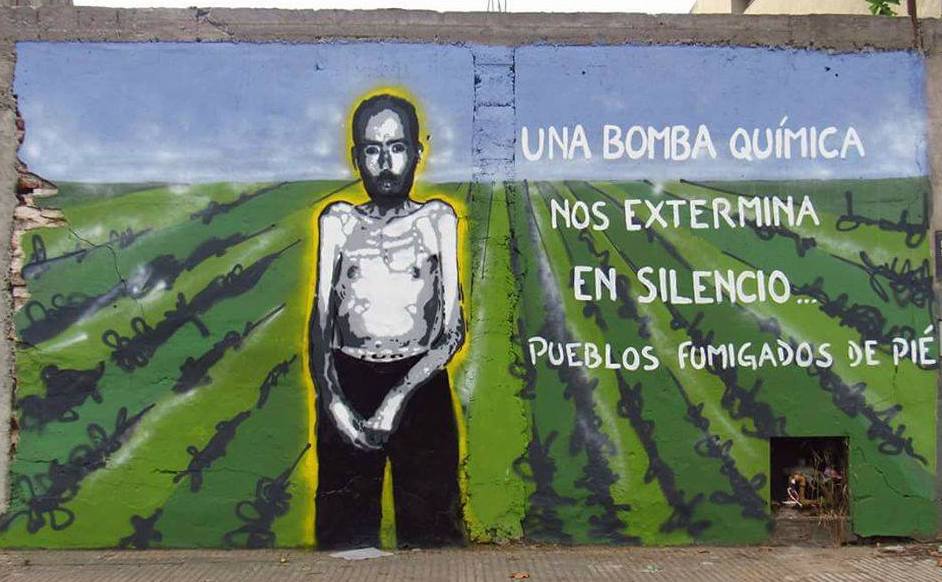

In response, growing networks of citizens have mobilized under the slogan Paren de Fumigarnos (Stop spraying us). The severity of the environmental health impacts have prompted them to invoke the shared cultural memory of state terrorism during the military dictatorship of 1976–1983 to characterize the ongoing soyification of the Argentine countryside as a “genocidio encubierto,” a “hidden genocide.”

Yet, despite these extreme impacts, the realm of institutionalized science in Argentina rarely advances any critiques of the agribusiness model. As a result, rural and peri-urban populations exposed to high levels of agrichemicals remain largely unprotected by state policy. In the context of a university system increasingly dominated by corporate influence, where capital’s stranglehold on what is considered acceptable science throws public health under the bus, the Ciencia Digna movement has emerged, posing the question: “Ciencia para qué y para quiénes?” (Science for what and for whom?)

Science for Sale? The Global Controversy over Glyphosate Herbicides

“Who pays whom, and who answers what to whom, has consequences for the sorts of knowledge fostered.”

—Philip Mirowksi and Esther-Mirjam Sent, “The Commercialization of Science, and the Response of STS,” in The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies, eds. Edward Hackett, Olga Amsterdamska, Michael Lynch, and Judy Wajcman (Boston: MIT Press, 2005), 671.

The impact of glyphosate on human health is the subject of fierce contestation on a global scale.19 Proponents of the herbicide argue that it is lethal to plants yet essentially non-toxic to vertebrates and that it is quickly broken down into harmless substances within the larger environment.20 The Monsanto company claims that more than 900 studies have demonstrated, beyond a shadow of a doubt, the innocuousness of glyphosate.21

However, independent scientific studies have linked glyphosate to several serious maladies, including cancer, kidney malfunction, and reproductive disorders. For example, Benachour et al. observed an association between glyphosate-based products and cell cycle deregulation—a “hallmark of tumor cells and human cancers”—and linked glyphosate exposure to adverse effects on human reproduction and fetal development.22 Gasnier et al. documented disruption of endocrine and kidney function at environmentally relevant concentrations.23 Benítez et al. linked glyphosate herbicides to congenital malformations in an epidemiological study of women in Encarnación, Paraguay.24

In March of 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a branch of the World Health Organization, reclassified glyphosate as a “probable carcinogen,” highlighting a link between glyphosate exposures and increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.25 Since the WHO reclassification, more than 13,400 lawsuits have been filed against Monsanto by farmers, landscapers, and agricultural workers in the United States who claim that their lymphoma was caused by exposure to Roundup.26 In March of 2017, a federal judge in San Francisco unsealed documents which reveal that Monsanto has exploited relationships within the Environmental Protection Agency to ensure prolonged regulatory approval of glyphosate despite accumulating evidence of its negative health impacts. The unsealed documents further suggest that the paper most often cited as evidence of the herbicide’s innocuousness (Williams, Kroes, and Munroe 2000) was ghostwritten by company scientists and then published under the names of Gary Williams, a pathologist at New York Medical College, and his co-authors.27

Indeed, “Monsanto’s ghostwriting has infected the scientific literature,” attorneys claim in recent lawsuits against the company.28 Exposés such as Carey Gillam’s Whitewash reveal the extent to which Monsanto has produced the illusion of a favorable scientific consensus through the recruiting of “credible scientists” to “report favorably” on its products and the systematic defamation of those who dare to dissent.29 Kara Cook-Schultz of the United States Public Research Interest Research Group argues, “Monsanto tells us that Roundup is safe because scientists say it is safe. But apparently scientists sign their names, while Monsanto signs the checks.”30

The North American agribusiness firm’s influence on scientific knowledge production extends far beyond U.S. borders. In Argentina, a 2009 review by the Ministry of Science and Health entitled “Evaluación de la información científica vinculada al glifosato en su incidencia sobre la salud y el ambiente” (Evaluation of scientific information related to glyphosate in its impact on health and the environment) found a lack of evidence that glyphosate negatively impacts human health.31 The official report, which was vigorously criticized by civil society organizations, repeatedly cites the work of the purportedly “independent” academic Gary Williams to defend the safety of glyphosate. Meanwhile, a recent (April 2019) ruling in the Entre Ríos province which bans agrichemical fumigations within 1000 meters of schools was criticized as “irresponsible” by President Mauricio Macri, who claimed that there is a lack of “scientific rigor” to justify legal limitations on agrichemical fumigation.32

Andrés Carrasco: Ciencia sin Patrón33

La ciencia no es neutral ni objetiva. La ciencia siempre tiene ideología y un sentido político. La ciencia puede aportar a la liberación o al sometimiento. La ciencia puede ser aliada de las corporaciones o estar al servicio del pueblo.

Science is neither neutral nor objective. Science always has ideology and a political meaning. Science can contribute to liberation or submission. Science can be allied with corporations or be at the service of the people.

— Darío Aranda, Homage to Andrés Carrasco: Science without a Boss.

Andrés Carrasco was a microbiologist who specialized in embryonic development, and the president of CONICET (Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council) in 2000 and 2001. After hearing reports of increased rates of birth and spinal defects in rural communities, Carrasco decided to research the possible effects of glyphosate on human health by conducting tests on frog and chicken embryos. When he discovered evidence of astoundingly strong effects, he decided to release his results to the public. He contacted Darío Aranda, one of the few journalists sympathetic to the plight of rural communities, and in April 2009 his story made it to the front page of Página 12, Argentina’s most widely circulated progressive newspaper. “If it’s possible to reproduce this in a laboratory, surely what is happening in the field is much worse,” Carrasco told the press. “And if it’s much worse… what we have to do is put this under a magnifying glass.”34

Almost immediately, anonymous threats began pouring in on the telephone, and a group of lawyers working for agribusiness stormed his office looking for papers and other research documents. Lino Barañao, the Argentine Minister of Science and Technology, rushed to publicly discredit Carrasco’s research and, as was later revealed in an email leak, privately implored the head of the National Committee of Ethics in Science and Technology to censure the microbiologist on ethical grounds.35 Wikileaks has further revealed that the US Embassy also lobbied against Carrasco during this time.36 A paper that condescendingly refuted Carrasco’s claims was later linked to the Swiss agribusiness firm Syngenta.37 In August 2010 Carrasco narrowly escaped being captured by an enraged mob of landowners and local politicians while in the Chaco for a speaking engagement.

Carrasco’s life as a well-respected but publicly unknown scientist was over. But his life as a leader and icon of an insurgent movement had just begun. He became an ally and advocate for the marginalized communities who were fighting the dispossession, displacement, and contamination generated by the technologically driven expansion of the agricultural frontier. Alicia Massarini, biologist and colleague of the late Carrasco, recalls that the scientist “did not position his study as absolute truth, but rather as a contribution that made sense together with other ways of knowing—those of the communities that for years have suffered, resisted, and insisted that agrochemicals sicken and kill.” Massarini further notes that his legacy has reinvigorated debates initiated in Latin America by Oscar Varsavsky, Amílcar Herrera, and Jorge Sábato about the non-neutrality of science and the need for a “pueblo-centric” model of investigation and innovation that puts communities first.38

Before Carrasco died of a heart attack in May of 2014, he formed important networks and alliances that persist, even as he cannot. The Red de Científicos Comprometidos (Network of Committed Scientists) is a growing organization of scientists and academics in Argentina, Mexico, Ecuador, Costa Rica, and Brazil guided by the principles of the Declaration for a Dignified Science. The declaration, penned by Carrasco days before his death, does not stop at the condemnation of glyphosate, but inveighs against agricultural biotechnology and other forms of extractivism as neocolonial pillaging and declaims forms of scientific investigation that are complicit in this corporatist neocolonial project.

Día de la Ciencia Digna

“Carrasco ya es semilla.”

Carrasco is a seed now.

—Darío Aranda

On June 16, 2014, at the School of Medicine of the University of Rosario, a group of scientists, activists, and community members marked Andrés Carrasco’s birthday by instituting The Day of Dignified Science. They sought not only to honor the legacy of Carrasco, but also to construct a network of militant “pueblo-centric” scientists (cientificos comprometidos). The day has since been expanded to a week during which, in different cities around Argentina, STEM professionals and members of affected communities discuss the socioenvironmental consequences of extractive GM agriculture, critique the role of corporate science in legitimating it, and work towards building a “pueblo-centric” science capable of dismantling it.

The 2018 gathering for Ciencia Digna in Rosario was the largest yet. It brought together radical scientists from Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, and Paraguay for the advancement of a transformative, decolonizing agenda rooted in Indigenous and Afro-descendent struggles for Food Sovereignty and Buen Vivir, and the idea of collective socioecological health based in territorial sovereignty.39

“Ciencia para qué y para quiénes?” Science for what and for whom?

“Andrés [Carrasco] was my friend, and you know, he didn’t believe in science, he believed in social movements,” Cristina told me as she peered down into her coffee. We were chatting during a break in one of the evening training sessions for the second round of the epidemiological survey in Barrio Ignacio Suárez. “He said that epidemiological studies are a strategy of resistance, because they’re a way of raising consciousness to generate a social movement.”

Years ago, under the progressive Kirchner government, Cristina had been employed as a researcher in a nuclear magnetic resonance laboratory. She remarked, “What I did in the laboratory—at first I thought I was helping humanity, but later I realized that, more than helping humanity, I was helping international pharmaceutical corporations.” Joining Paren de Fumigar helped radicalize her, and she asked to be transferred to the Superior Institute of Environmental Studies at the National University of Córdoba.

There [in the institute] my mission was supposedly to generate projects that would serve society and the environment, and I helped to create the Environmental and Epidemiological Observatory of Populations Exposed to Agrochemicals in the Province of Córdoba. But we received a lot of funds from the federal government, which was in turn being funded by GM soy. President Kirchner announced the installation of the Monsanto plant in Córdoba, which from the beginning was controversial with residents but was something that the government was totally in favor of. Obviously they are going to support soy because that is where their money was coming from. This country runs on transgenic soy and corn. Anyway, given all this, to denounce the soy model from the university was something that just couldn’t be done. So when people learned what we were doing with this project, we were ordered to shut up. I was taken out of my leadership role and one of my collaborators who was a staunch Kirchnerista was put in charge of the Observatory to ensure that nothing would be accomplished there. From then on, every time I spoke of the need to apply our expertise to the explosion of disease in the countryside, I was told ‘It’s too big, it’s too big a problem.’ Or ‘What we need to be producing here is academic data that has been published in an academic journal.’ So imagine, I said, ‘Well this isn’t going to work, because the people are contaminated now. They don’t have two years to wait for this paper to be published.’ And that’s how all this came about, this project based on community epidemiology… And that’s why university subsidies don’t work—because when you become institutionalized, you’re [prevented from] acting in the service of the population.

Cristina’s story illustrates the steep challenges faced by scientists in a world increasingly dominated by corporate influence. Under the Kirchner government, scientific innovation was promoted as a value and funded by the state. But the role of science was clearly defined: to bolster economic growth and “add value” to the economy. Between 2012 and 2015, political leaders instituted a national plan for “science, technology, and innovation” called Argentina Innovadora 2020 (Innovative Argentina 2020). The plan conspicuously emphasizes “the unity of knowledge and the economy,” and promotes collaboration between the private sector and universities, “because that’s what all the developed countries of the world do to add value.”40 Kirchnerism paid lip service to independent scientific investigation in the abstract, but the increasingly permeable boundaries between the university and the private sector ensured that critical investigation of the ecocidal soy production model from within the scientific establishment “just couldn’t be done.”

Now, the right wing Macri government has implemented a brutal austerity regime which threatens to dissolve public science institutions and eliminate any lingering bureaucratic obstacles to bald-faced corporate technocracy. In 2018 and 2019, Argentina has seen runaway inflation and massive cuts to science and education, with scientists’ salaries and funds for investigation diverted to paying for newly-incurred IMF debt.

On Friday, April 5, news broke that, because of budget cuts, 83 percent of early career researchers in precarious post-doc and adjunct positions would not gain stable employment with CONICET. This move, which has been declaimed as “a scientific strategy for the development of agribusiness corporations, petroleum extraction, and megamining, prompted nationwide protests on April 10th, the Argentine Day of Science and Technology.41

A young biological anthropologist addressed the seething crowd that had gathered in one of Córdoba’s main plazas:

On this Day of the Scientific Researcher we’re out in the streets to voice our opposition to this neoliberal gutting strategy which seeks to justify the privatization of knowledge. But we also urgently need to imagine and bring about a form of science that serves another model of production, consumption, socio-environmental development, and real democracy. It’s crucial that we define another path for Science and Technology, one that roots its priorities in the needs of the pueblo and not of the market.

Parallel movements for Radical Science and Ciencia Digna in North and South America challenge us to move beyond the knee-jerk liberal scientism which shores up green capitalism and corporate hegemony, and invite us to ask, in the face of advancing socioecological catastrophe, science for what and for whom?

I would like to thank Emma Harnisch, Sigrid Schmalzer, and Marco Baity Jesi for their insightful comments on previous drafts of this article.

About the Author

Ingrid Feeney is a PhD student in Sociocultural Anthropology and Environmental Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She holds a BA in Linguistics from CUNY Brooklyn College and an MA in Anthropology from the University of Chicago. In addition to researching the agroecological transition in Argentina, Ingrid is a singer and a volunteer for the Nantucket Marine Mammal Association stranding response team.

References

- Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the safety of individuals.

- Carey Gillam, Whitewash: The Story of a Weed Killer, Cancer, and the Corruption of Science (Washington DC: Island Press, 2017), 156.

- The murga is a musical and theatrical genre particular to Spain and certain Latin American countries. Murga groups perform at local festivals, in particular during carnaval.

- A. Paganelli, V. Gnazzo, H. Acosta, S.L. López, and A.E. Carrasco, “Glyphosate-Based Herbicides Produce Teratogenic Effects on Vertebrates by Impairing Retinoic Acid Signaling,” Chemical Research in Toxicology 23, no. 10 (2010): 1586-1594, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/tx1001749.

- Benbrook, Charles M. “Trends in Glyphosate Herbicide Use in the United States and Globally,” Environmental Sciences Europe 28, no. 1 (2016): 3.

- Benbrook, “Trends in Glyphosate Herbicide Use in the United States and Globally,” 10.

- Carlos Menem was president of Argentina from 1989 to 1999. His openly neoliberal policies created a friendly climate for foreign investment, including transnational agribusiness. The successive presidencies of Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner from 2003 to 2015 saw a period of center-left governance in Argentina which is understood as part of the Latin American “pink tide” of the early twenty-first century. However, despite the somewhat anti-imperialist discourse of Kirchnerismo, Kirchnerist political strategy entailed “bringing back the state” using the revenues generated by GM soy. Therefore, the GM soy model was further entrenched under the Kirchner dynasty.

- Miguel Teubal, “Genetically Modified Soybeans and the Crisis of Argentina’s Agricultural Model” in Food for the Few: Neoliberal Globalism and Biotechnology in Latin America, ed. Gerardo Otero (Austin: U of Texas, 2008), 189-216.

- Lucia Goldfarb and Annelies Zoomers, “The Drivers Behind the Rapid Expansion of Genetically Modified Soya Production into the Chaco Region of Argentina,” Biofuels – Economy, Environment and Sustainability (2013): 73-95, https://doi:10.5772/53447.

- Goldfarb and Zoomers, “The Drivers Behind the Rapid Expansion of Genetically Modified Soya Production into the Chaco Region of Argentina,” 74.

- M. Avila-Vazquez and F.S. Difilippo, “Agricultura Tóxica y Pueblos Fumigados de Argentina” [Toxic Agriculture and Sprayed Communities of Argentina], Crítica y Resistencias. Revista de conflictos sociales latinoamericanos, 2 (2016): 23-45, http://criticayresistencias.comunis.com.ar.

- Vanesa Rosales de la Quintana, “La muerte regada: glifosato y cancer en la Argentina” [Watered death: glyphosate and cancer in Argentina], Agencia Paco Urondo Periodismo Militante, November 18, 2018, http://www.agenciapacourondo.com.ar/opinion/la-muerte-regada-glifosato-y-cancer-en-la-argentina. Luis Vazquez, “En Argentina se tiran 7,6 litros de agrotóxicos por persona por año, en Estados Unidos 0,4 litros” [In Argentina 7.6 liters of agrichemicals are applied per person per year, in the United States, 0.4 liters], Polos Productivos Regionales, April 10, 2019, http://www.polosproductivosreg.com.ar/2019/04/10/en-argentina-se-tiran-76-litros-de-agrotoxicos-por-persona-por-ano-en-estados-unidos-04-litros/.

- M. Avila-Vazquez, F.S. Difilippo, B.M. Lean, E. Maturano, and A. Etchegoyen,” Environmental Exposure to Glyphosate and Reproductive Health Impacts in Agricultural Population of Argentina,” 242.

- Avila-Vazquez and Difilippo, “Agricultura Tóxica y Pueblos Fumigados de Argentina” [Toxic Agriculture and Sprayed Communities of Argentina], 29.

- “Argentina: Análisis de la salud colectiva ambiental de Malvinas Argentinas-Córdoba” [Argentina: Analysis of collective environmental health of Malvinas, Córdoba], last modified February 25, 2013, http://www.biodiversidadla.org/Documentos/Argentina_Analisis_de_la_salud_colectiva_ambiental_de_Malvinas_Argentinas-Cordoba.

- Lucas L. Alonso, Pablo M. Demetrio, Agustina M. Etchegoyen, and Damián J. Marino, “Glyphosate and Atrazine in Rainfall and Soils in Agroproductive Areas of the Pampas Region in Argentina,” Science of the Total Environment, 645 (2018): 89-96, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.134; “Altos niveles de glifosato e insecticidas amenazan la vida acuática en toda la cuenca del Paraná” [High levels of glyphosate and insecticides threaten aquatic life in the entire Paraná River Basin], Diario del Norte, January 30, 2017, http://www.diarionorte.com/article/147921/altos-niveles-de-glifosato-e-insecticidas-amenazan-la-vida-acuatica-en-toda-la-cuenca-del-parana; “Según investigadores del Conicet, Urdinarrain, líder mundial de contaminación por Glifosato” [According to CONICET researchers, Urdinarrain, world leader in glyphosate contamination], 30 Días de Noticias, November 8, 2017, https://30diasdenoticias.com.ar/nota/6721-urdinarrain-lider-mundial-de-contaminacion-por-glifosato.

- “Hallan 34 cóndores muertos en Mendoza: Sospechan que fueron envenenados” [34 condors found dead in Mendoza: it’s suspected that they were poisoned], El Diario 24, January 22, 2018, https://www.eldiario24.com/nota/argentina/413108/hallan-34-condores-muertos-mendoza-sospechan-fueron-envenenados.html; Mariana Escalada and Agustin Ronconi, “Agroquímicos en Córdoba: 72 millones de abejas muertas” [Agrochemicals in Córdoba: 72 million bees dead], El Disenso, March 26, 2018, https://www.eldisenso.com/informes/agroquimicos-en-cordoba-72-millones-de-abejas-muertas/.

- Uki Goñi, “When nature says ‘Enough!’: the river that appeared overnight in Argentina,” The Guardian, April 1, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/apr/01/argentina-new-river-soya-beans.

- See the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s (AAAS) recent “reassessment” of its decision to give the 2019 Award for Scientific Freedom and Responsibility to two Sri Lankan researchers whose work indicates a link between glyphosate exposure and kidney disease: https://www.gmwatch.org/en/news/latest-news/18757-aaas-reassessing-award-to-public-interest-scientists.

- Christine Dubois and Ivan Sergio Freire De Sousa, “Genetically Engineered Soy,” in The World of Soy, eds. Christine Dubois, Chee-Beng Tan, and Sidney Mintz (Urbana: U of Illinois, 2008), 74-96;G. von Mérey, P.S. Manson, A. Mehrsheikh, P. Sutton, and S. Levine, “Glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid chronic risk assessment for soil biota,” Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 35, no. 11 (2016): 2742-2752, https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3438.

- “Frequently Asked Questions about Glyphosate,”Monsanto Company, accessed March 1, 2019, https://monsanto.com/resource-library/.

- J. Marc, O. Mulner-Lorillon, and R. Bellé, “Glyphosate-based pesticides affect cell cycle regulation,” Biology of the Cell, 96, no. 3 (2004): 245-249, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biolcel.2003.11.010.

- Céline Gasnier et al., “Glyphosate-based herbicides are toxic and endocrine disruptors in human cell lines,” Toxicology 262, no. 3 (2009): 184-191.

- S. Benítez Leite, M.L. Macchi, and M. Acosta, “Malformaciones congénitas asociadas a agrotóxicos” [Congenital malformations associated with agrochemicals], Archivos de Pediatría del Uruguay 80 (2009): 237–247.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, “Press release: IARC Monographs Volume 112: evaluation of five organophosphate insecticides and herbicides,” March 20, 2015, ,https://www.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/MonographVolume112-1.pdf.

- A significant blow to Bayer-Monsanto, federal juries have recently ruled that Roundup caused the cancers of Dewayne Johnson (2018) and Edwin Hardeman (2019). “CA Jury Finds Monsanto’s Roundup Guilty of Causing Man’s Cancer,” Democracy Now, March 20, 2019, https://www.democracynow.org/2019/3/20/headlines/ca_jury_finds_monsantos_roundup_guilty_of_causing_mans_cancer.

- Warren Cornwall, “Update: after quick review, medical school says no evidence Monsanto ghostwrote professor’s paper,” Science, March 23, 2017, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/03/update-after-quick-review-medical-school-says-no-evidence-monsanto-ghostwrote. Danny Hakim, “Monsanto Weed Killer Roundup Faces New Doubts on Safety in Unsealed Documents,” The New York Times, March 14, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/14/business/monsanto-roundup-safety-lawsuit.html.

- Gillam, Whitewash, 88.

- Gillam, Whitewash, 88-89.

- Gillam, Whitewash, 89.

- Consejo Nacional De Investigaciones Científicas Y Técnicas (CONICET), “Evaluación De La Información Científica Vinculada Al Glifosato En Su Incidencia Sobre La Salud Y El Ambiente” [Evaluation of scientific information related to glyphosate in its impact on health and the environment], N.p.: n.p., 2009.

- “Macri Defendió el Uso de Agrotóxicos sin Control” [Macri defended the uncontrolled use of agrochemicals], Pagina 12, April 4 2019, https://www.pagina12.com.ar/185254-macri-defendio-el-uso-de-agrotoxicos-sin-control.

- Darío Aranda. “Homenaje a Andrés Carrasco: Ciencia Sin Patrón.” [Science without a boss.], La Vaca., July 30, 2014. https://www.lavaca.org/notas/homenaje-a-andres-carrasco-ciencia-sin-patron/.

- Michael Warren and Natacha Pisarenko, “Birth Defects, Cancer in Argentina Linked to Agrochemicals: AP Investigation,” Associated Press, October 21, 2013, http://www.ctvnews.ca/health/birth-defects-cancer-in-argentina-linked-to-agrochemicals-ap-investigation-1.1505096.

- Adamovsky, Ezequiel, “Andres Carrasco vs Monsanto,” TeleSUR English, July 17, 2017, https://www.telesurenglish.net/opinion/Andres-Carrasco-vs-Monsanto-20141001-0090.html.

- “Glyphosate Herbicide, a Catalyst for Argentine Politics,” diplomatic cable, May 7, 2009, https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/elpais/subnotas/163729-52437-2011-03-09.html.

- J.B. Fagan and C. J. Robinson, “Teratogenic effects of glyphosate-based herbicides and political and scientific controversy,” Journal of Environmental and Analytical Toxicology 4 (2012), http://doi:10.4172/2161-0525.S4-006.

- Darío Aranda, “Homenaje a Andrés Carrasco: Ciencia Sin Patrón” [Homage to Andrés Carrasco: Science without a boss], La Vaca, July 30, 2014, https://www.lavaca.org/notas/homenaje-a-andres-carrasco-ciencia-sin-patron/.

- Declaration of the Network of Scientists Committed to Society and Nature. Rosario, November 13, 2018. https://redtecla.org/noticias/encuentro-2018-por-la-ciencia-digna.

- Argentina. Ministerio De Ciencia, Tecnología E Innovación Productiva. Secretaría De Planeamiento Y Políticas En Ciencia, Tecnología E Innovación Productiva. Argentina Innovadora 2020: Plan Nacional De Ciencia, Tecnología E Innovación [Innovative Argentina 2020: National Plan for Science, Technology, and Innovation], N.p., December 8, 2011.

- Luciana Nogueira, “Más de 2.100 científicos del Conicet quedaron en la calle” [More than 2,100 scientists from CONICET were left in the street], La Izquierda Diario, April 6, 2019, http://www.laizquierdadiario.com/Mas-de-2-100-cientificos-del-Conicet-quedaron-en-la-calle?utm_content=buffer810c1&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook.com&utm_campaign=buffer&fbclid=IwAR0NqAcRKaPpfvSS8xWebEWyO6bCUOINwWVkWijwKDgNPuejNkZ128KfqJE.