Settler colonialism and pandemics

Native Americans misrepresented in health data pay a heavy COVID-19 price

By Brianna Johns, Michael Caslin, Michael Lewis, Karletta Chief, and Madhusudan Katti

Volume 23, number 3, Bio-Politics

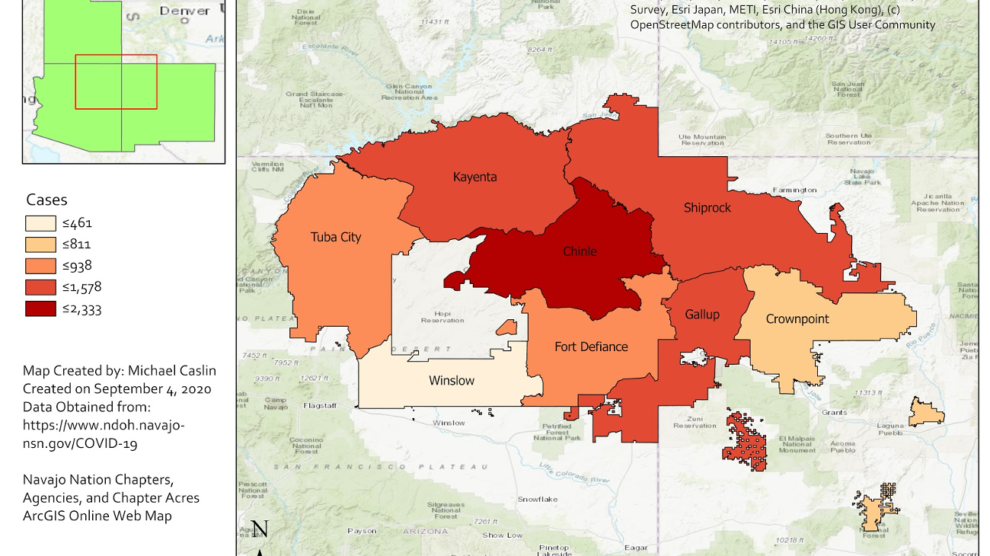

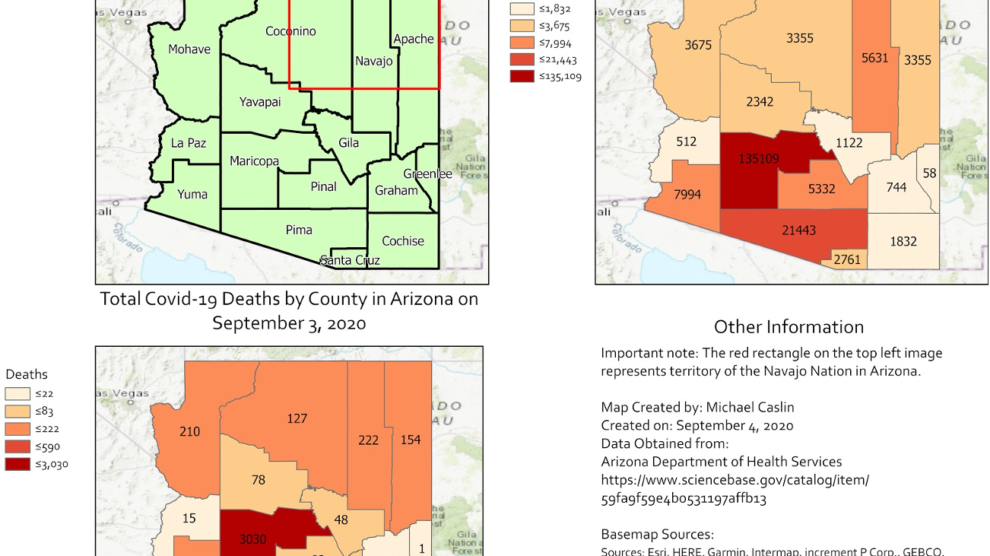

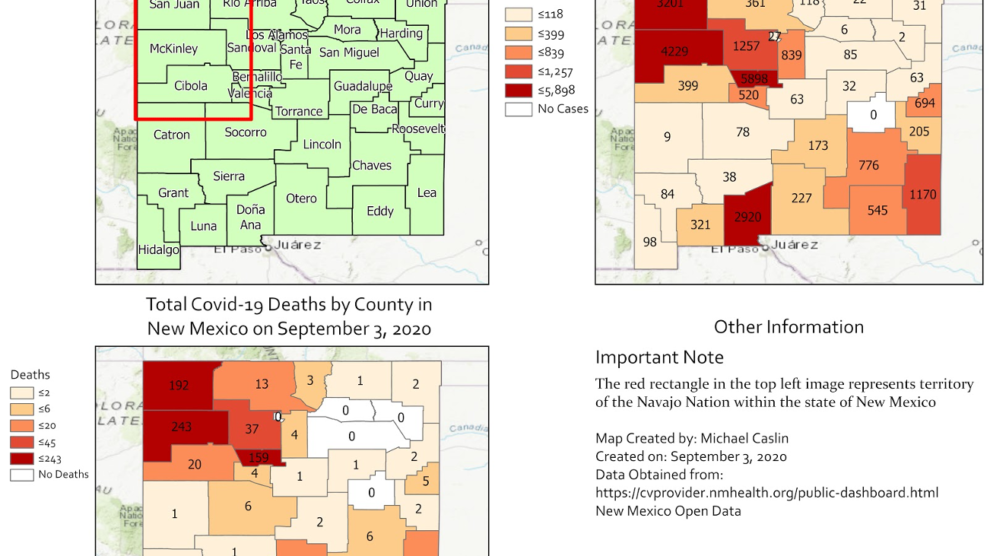

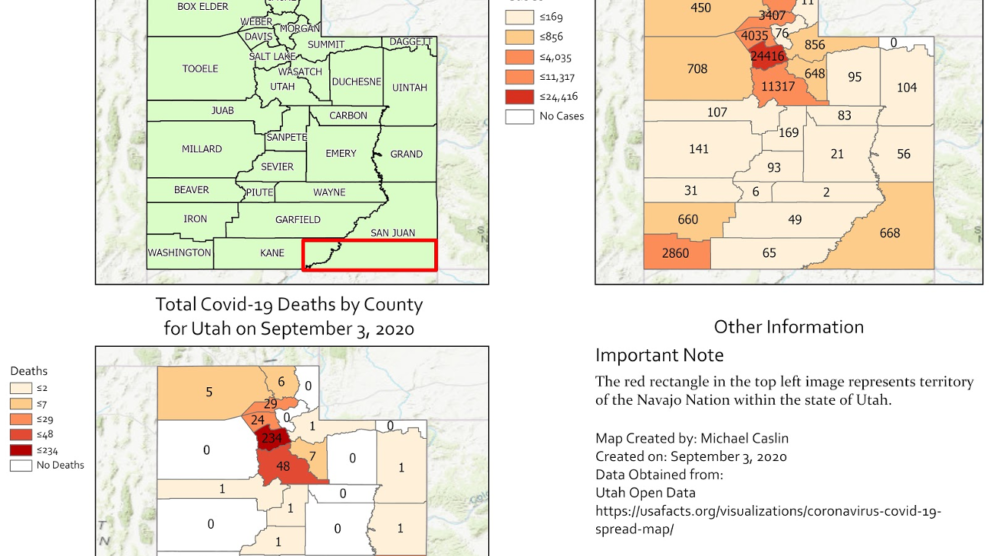

In March 2020, New York City became the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, as the virus spread exponentially through the densely populated city. But, almost unnoticed by national media, the virus was spreading at an even faster rate in an unlikely community at the other end of the spectrum of American life. By May, the Navajo Nation, the largest Native American tribe in the United States, overtook New York with the highest per capita infection rate of COVID-19.1 Our maps, included below, show the spread of COVID-19 across the Navajo Nation by September 2020. We combined data from the four states—Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah—that the Nation overlaps with to visualize the severity of the pandemic. As of this writing, the virus has infected more than 26,000 people and taken more than 900 lives from the Diné (as people of the Navajo Nation call themselves).

The Diné are not alone among Indigenous communities hit hard by this virus, but the full extent of the impact on all Indigenous people in the US is hard to gauge. Data on COVID-19 within Native and Indigenous communities is a “national disgrace,” according to Abigail Echo-Hawk, director of the Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) based in Seattle.2 Echo-Hawk is co-author on a recent report that estimates that American Indian and Alaskan Natives are 3.5 times more likely to be infected with COVID-19 than non-Hispanic white people.3 However, these conclusions are limited by the fact that data is only available from twenty-three states. These stark figures illustrate the immense disparities in healthcare and public investment in Native and Indigenous communities across the United States. These disparities are rooted in histories and strategies of neglect, erasure, and undercounting—and therefore underfunding.4 Indigenous peoples have always endured the worst outcomes of pandemics, which often originate in, and are perpetuated by, European settler-colonialism.

These disparities are rooted in histories and strategies of neglect, erasure, and undercounting—and therefore underfunding.

When Europeans first came to the Americas they spread, sometimes deliberately, a wide range of diseases, including smallpox, measles, and influenza, resulting in the death of twenty million Native Americans. This was a dominant factor in the estimated 95 percent decline of the Native population following European contact.5 Once again, in the 1918 influenza pandemic—which killed 50 million people worldwide—Native Americans were hit hard, with mortality rates four times that of the wider population (comparable to 3.5 times for COVID-19).6 Around one-tenth of the Diné population died following three waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic.7 So what made the 1918 flu so deadly to Native Americans?

According to Benjamin Brady, then a graduate student at the University of Arizona, and Howard Bahr, emeritus professor of sociology at Brigham Young University in Utah, the Diné suffered disproportionately because of “federal neglect in preventive care, communication, and provision of care during the epidemic.”8 In addition, the federal government placed the blame on local administrators and resisted attempts by Native agencies to accurately reflect the real death toll in vital statistics.9 Researchers also implicated a litany of other factors, including age and gender, community and communication infrastructure, the availability of nursing, food and shelter, and differences in social distancing.10

Click the maps above to expand for a full accounting of the COVID pandemic in Navajo Nation territory as of September 3, 2020

Native Americans have experienced outbreaks of other infectious diseases, ranging from the Hantavirus outbreak of the early 1990s in the Four Corners Region of the US that includes the Diné, to the ongoing resurgence of tuberculosis among Indigenous peoples worldwide.11 The disastrous relationship between settler-colonialism and pandemics has become increasingly apparent with the current COVID-19 pandemic.12

Tribal leaders and Indigenous researchers attribute the rapid spread of COVID-19 across tribal lands to the lack of reliable access to water for handwashing, food shortages, and inadequate or nonexistent public health messaging in the local language.13 Medical science has begun to pay attention to the social and economic factors that lead to disparities in health and the impact of COVID-19 on Native Americans.14 Yet some researchers focus on genetic differences to explain susceptibility to the virus, such as higher levels of ACE-2 receptors, which the virus uses to enter cells.15 Health conditions such as diabetes (also partly attributed to genetics) are also used to explain the high infection rate among the Navajo. This is a well-worn slippery slope where biomedical science stereotypes Native Americans, and other non-white racial groups in ways that compound cultural biases and influence the potential quality of care from colonial medical systems.16 we are to understand and break the recurring cycle of epidemics that impact Native Americans, we must confront how deeply settler colonialism and white supremacy is woven into the fabric of the United States.

The U.S. has systematically ignored, suppressed, and manipulated data on Native American populations, violating their sovereignty and creating the gulf in healthcare access and outcomes. For example, the US failed to include Native Americans in census data until 1860.17 When they were eventually included, the government used this data to track tribal populations in the nineteenth century to expel people from their lands and to take their children.18 These historical legacies inevitably led to a distrust of the federal government and these attempts to gather data.19 Today, the undercounting of Native Americans continues in barriers to access in census form design and language, misrepresentation in categorization, and a lack of understanding of ethnic and tribal affiliations.20 Furthermore, a large majority of Native Americans living in cities are excluded from the census.21 Over seventy percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives who live off federally designated tribal lands are miscounted or left out of total population counts altogether.22

Today, the undercounting of Native Americans continues in barriers to access in census form design and language, misrepresentation in categorization, and a lack of understanding of ethnic and tribal affiliations.

In 2010, Native Americans were the most undercounted population in the census. While in 2020, the US Census Bureau ended field data collection a month early, likely compounding further undercounting and thus underrepresentation of Indigenous tribes as these communities are hard-to-reach for census surveys.23 This data determines how health funding will be allocated, and thus undercounting directly impacts infrastructure and access to testing and medical care, essential for tracking and mitigation strategies deployed during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the Indian Health Service, a government agency responsible for supporting federally-recognized Native American Tribes and Alaska Native people, is severely underfunded.24 Furthermore, the recent CARES Act (the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act) allocated funding only to Native and Indigenous people residing on reservations and related tribal areas.25

Advocacy by Congress members, alongside grassroots initiatives such as Census Bureau Partners, which employs community members, are beginning to improve accounting for Indigenous populations in census data and other national vital statistics. The UIHI also works to decolonize data, by “reclaiming the Indigenous values of data collection, analysis, and research, for Indigenous people, by Indigenous people.”26 For example, UIHI’s “Our Bodies, Our Stories” project collects and analyzes data on sexual violence against Native American women.27 The project sheds light on the mismanagement and missed opportunities in data collection by law enforcement agencies for national, and state databases. The “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls” report highlights how Indigenous women and girls are severely undercounted, making it difficult to capture accurate rates of violent but often invisible domestic crimes. Without reliable data, Indigenous communities are faced with challenges.28

Underrepresented and under-resourced during the COVID-19 pandemic, groups like the UIHI have become leaders in the fight against the virus in Indigenous communities. Led by the fierce advocacy of Echo-Hawk, the UIHI collects and disseminates data from Native and Indigenous communities with cultural relevance for communities that include urban Indians, those who are dealing with unstable living conditions or on the streets, and those who are at risk due to concurrent health concerns like diabetes, HIV/AIDS or cardiovascular conditions. The UIHI’s website provides a wealth of information for Native and Indigenous communities, filling gaps and vacancies in care left by the federal government.29

In an effort to decolonize and decentralize data, the UIHI and Echo-Hawk’s work, along with other stories of advocacy and action, are crucial to combating the historical legacies of settler colonialism in the US—but they cannot do this alone. For any COVID-19 treatment strategy to be effective, epidemiologists and public health authorities must grapple with their own complicity in these socioeconomic disparities and racial inequalities. To end on a quote from UIHI, “American Indians and Alaska Natives were once the healthiest people in these lands”—but colonial histories have directly contributed to the unacceptable vulnerabilities and risks that Indigenous peoples continue to endure with this pandemic. If we fail to grapple with this, the next virus will inevitably blaze another deadly trail among Indigenous peoples, as COVID-19 is doing now, and as so many other diseases have done in the past.

About the Authors

Brianna Johns is a recent graduate from North Carolina State University with a bachelor of science in Zoology and a bachelor of arts in International Studies. Brianna has been involved in several public science initiatives at NC State, where she was a founding member of the Citizen Science Club at NC State. She currently co-hosts a podcast titled Queer Science.

Michael Caslin is currently a PhD student in Forestry and Environmental Resources at North Carolina State University applying Geospatial Technology to research.

Michael Lewis is currently a graduate student at NC State University studying Informal STEM Education. He aims to connect with underrepresented populations in STEM and to increase the feeling of belonging through community engagement.

- Twitter: @TheGuy7991

Karletta Chief, PhD, is an Associate Professor and Extension Specialist in the Department of Environmental Science at the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona. She works to bring relevant science to Native American communities in a culturally sensitive manner by providing hydrology expertise, transferring knowledge, assessing information needs, and developing applied science projects. She is Diné (Navajo) from Black Mesa, Arizona, and was raised without electricity or running water. She is a first-generation college graduate.

Madhusudan Katti, PhD, studied migrant birds wintering in his native India for his PhD. His first stint as a professor in Fresno, California, deepened his commitment to science communication and citizen science. Now an Associate Professor in North Carolina State University’s Chancellor’s Faculty Excellence Program for Leadership in Public Science, he teaches “Decolonizing Science” and engages local communities in studying how human activities and histories of colonization and segregation reshape the urban geography of nature.

- Twitter: @leafwarbler

- Facebook: /madhusudan

- Instagram: @leafwarbler

References

- Hollie Silverman, Konstantin Toropin, and Sara Sidner, “Navajo Nation Surpasses New York State for the Highest Covid-19 Infection Rate in the US,” CNN, May 18, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/18/us/navajo-nation-infection-rate-trnd/index.html.

- Lizzie Wade, “Fighting to Be Counted,” Science 369, no. 6511 (September 25, 2020): 1551–52, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.369.6511.1551.

- Sarah M. Hatcher et al., “COVID-19 Among American Indian and Alaska Native Persons — 23 States, January 31–July 3, 2020,” MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69 (2020), https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6934e1.

- Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear et al., “American Indian Reservations and COVID-19: Correlates of Early Infection Rates in the Pandemic,” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 26, no. 4 (August 2020): 371–377, https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001206.

- Russell Thornton, American Indian Holocaust and Survival: A Population History Since 1492, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987). 43.

- Benjamin R. Brady and Howard M. Bahr, “The Influenza Epidemic of 1918–1920 among the Navajos: Marginality, Mortality, and the Implications of Some Neglected Eyewitness Accounts,” American Indian Quarterly 38, no. 4 (2014): 459–491, https://doi.org/10.5250/amerindiquar.38.4.0459; Sarah M. Hatcher et al., “COVID-19 Among American Indian and Alaska Native Persons.”

- Brady & Bahr

- Brady & Bahr 483

- Brady & Bahr 483

- Brady & Bahr 461, 466

- Susan Borowski, “The Virus that Rocked the Four Corners Reemerges” Scientia,, January 8, 2013, https://www.aaas.org/virus-rocked-four-corners-reemerges; Maxime Cormier et al., “Proximate Determinants of Tuberculosis in Indigenous Peoples Worldwide: A Systematic Review,” The Lancet Global Health 7, no. 1 (January 1, 2019): e68–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30435-2.

- Sarah M. Hatcher et al., “COVID-19 Among American Indian and Alaska Native Persons.”

- Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear et al., “American Indian Reservations and COVID-19: Correlates of Early Infection Rates in the Pandemic,” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 26, no. 4 (2020): pp. 371–377, https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001206.

- Monika Kakol, Dona Upson and Akshay Sood, “Susceptibility of Southwestern American Indian Tribes to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19),” The Journal of Rural Health, accepted April 18, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12451.

- Joseph De Soto and Shazia Hakim, “Medical Basis for Increased Susceptibility of COVID-19 among the Navajo and other Indigenous Tribes,” preprints, submitted April 13, 2020, https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202004.0217.v1.

- Anthony Ryan Hatch, “Technoscience, Racism, and the Metabolic Syndrome,” in Kelly Moore and Daniel Lee Kleinman, ed. Routledge Handbook of Science, Technology, and Society (Oxford: Routledge, 2014), 39–55.

- “Censuses of American Indians,” U.S. Census Bureau https://www.census.gov/history/www/genealogy/decennial_census_records/censuses_of_american_indians.html.

- Kirsten Carlson, “Indian Country Leaders Urge Native People to Be Counted in 2020 Census,” The Conversation, March 11, 2020, http://theconversation.com/indian-country-leaders-urge-native-people-to-be-counted-in-2020-census-132419.

- Kirsten Carlson, “Indian Country Leaders Urge Native People to Be Counted in 2020 Census.”

- Carlson, “Indian Country”; Kim Tallbear, Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

- Annita Lucchesi and Abigail Echo-Hawk, “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls” (Seattle, WA: Urban Indian Health Institute, 2018), 1–30.

- Jennifer Bendery, “‘Devastating’: The Census Bureau Is About To Severely Undercount Tribes,” HuffPost, August 16, 2020, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/census-bureau-2020-native-american-tribes-undercount_n_5f355270c5b6960c0671ca77; Eric Henson et al., “Federal COVID‐19 Response Funding for Tribal Governments: Lessons from the CARES Act,” July 24, 2020, https://ash.harvard.edu/publications/hpaied-policy-brief-0.

- Jennifer Bendery, “‘’Devastating’’: The Census Bureau Is About To Severely Undercount Tribes;” Rebecca Nagle, “‘We Are Still Here’: Native Americans Fight to be Counted in US Census,” The Guardian, January 15, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jan/15/we-are-still-here-native-americans-fight-to-be-counted-in-us-census.

- Mark Walker, “Pandemic Highlights Deep-Rooted Problems in Indian Health Service,” New York Times, October 9, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/29/us/politics/coronavirus-indian-health-service.html

- Eric Henson et al., “Federal COVID‐19 Response Funding for Tribal Governments.”

- Annita Lucchesi & Abigail Echo-Hawk, “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls,” 23.

- Urban Indian Health Institute, “Our Bodies, Our Stories,” June 25, 2020, https://www.uihi.org/projects/our-bodies-our-stories/.

- Annita Lucchesi and Abigail Echo-Hawk, “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls.”

- Urban Indian Health Institute, COVID-19, https://www.uihi.org/projects/covid/.