Organize the Lab: Theory and Practice

Chapter 6

Out from Under the Umbrella

By Lizzy Karnaukh

As thousands of academic workers in the United States strive to unionize across different university campuses, many organizing campaigns struggle to engage a key demographic: PhD students in STEM departments. Reasons for hesitation among STEM students include fear of losing money from paying union dues, satisfaction with certain working conditions, and a strong belief that it is supposed to be hard to obtain a PhD, just as it was for the professors and predecessors before them. Such reasons are unrelated to discipline, as similar hesitation can be found amid other departments but they tend to be more pronounced in STEM.

Yet many STEM graduate students are not covered by dental or vision insurance, experience gaps in pay, and have no codified workers compensation for workplace accidents. In one instance, when chemistry graduate student Shiva Dastjerdi suffered a chemical burn while performing routine lab work, Boston University (BU) refused to pay her hospital bills as they “believed that because she was working on her PhD research when the accident happened, her work didn’t further BU’s interests.”1 STEM graduate students are also more likely than others to experience sexual harassment due to the one-on-one apprenticeship model in labs; prevalence of abusive mentors; and general cultures of machismo, racism, and sexism.2 Many STEM graduate workers do support unionization that assures more transparent grievance procedures, guarantees timely payment that keeps up with the cost of living, and ensures fair distribution of teaching and research labor.3

In general, graduate workers often choose to negotiate as university employees to achieve better working conditions and sustain a larger movement towards meaningful change. To do this, they also rely on relationships between local collectives of workers and international labor unions such as the United Auto Workers (UAW), Service Employees International Union (SEIU), American Federation of Teachers (AFT), American Association of University Professors (AAUP), and United Electrical Workers (UE). These larger union organizations offer training, legal aid, experienced staffers, media consulting, and other resources for nascent campaigns; ultimately, these resources are shared in solidarity with local workers to win union elections. In return, upon a successful union election, graduate workers join the larger organization as dues-paying members. While this traditional pairing resulted in union victories for workers in higher education at New York University (NYU), Columbia University, Harvard, and others, it has not had a widespread effect across academia; most graduate workers remain nonunionized.4 Many campaigns struggle to launch beyond the initial stage of amassing majority support for unionization. Organizing strategies are similar across campaigns, and graduate students have similar goals in unionizing; so why are some graduate unions trailing behind others?

A cursory glance shows that union membership since the 1970s has declined in the United States, even as working conditions have worsened for different kinds of employees. Given that public approval of unions is on an upward trend, especially among younger generations, why has union membership hit an all-time-low in recent years?5 The barriers to successfully organize a union seem endless, particularly in the private sector; in particular, the right has led a systematic, decades-long assault on labor. Bosses across firms have spent up to a total of $340 million hiring lawyers and consultants who specialize in anti-union tactics.6 Individualism permeates US culture, employers regularly stall contract negotiations, and globalization has moved domestic manufacturing offshore. The Supreme Court’s 2021 Janus ruling has slashed key financial resources for parent unions7 as “right-to-work” legislation in states such as Wisconsin has decimated public union budgets. The power of such external forces in hindering union campaigns is well-documented across all sectors, industrial and academic.

Beyond these external barriers, internal dynamics and mechanisms within graduate unionization campaigns also exist as obstacles at the ground level. Exposing the core of these challenges, I focus on the following questions: What kind of organizing strategies and tactics are utilized by graduate workers and international “umbrella” unions? Have traditional organizing models been adapted to fit the needs of academic labor campaigns? Do traditional organizing models confer long-term material benefits to STEM graduate students?

Organizing Strategies and Shortcuts

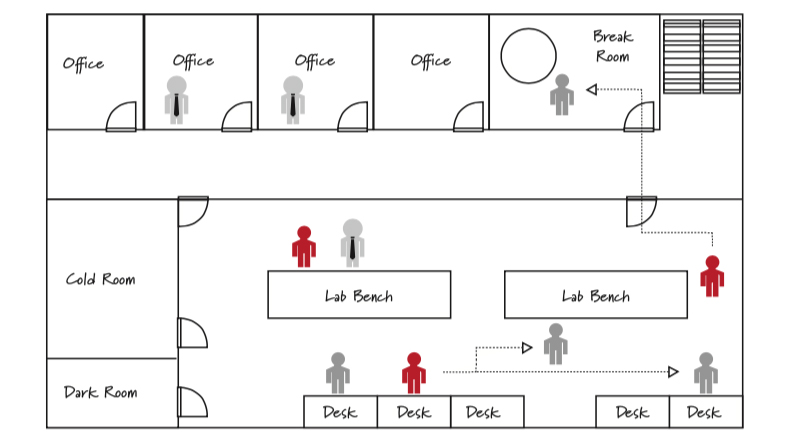

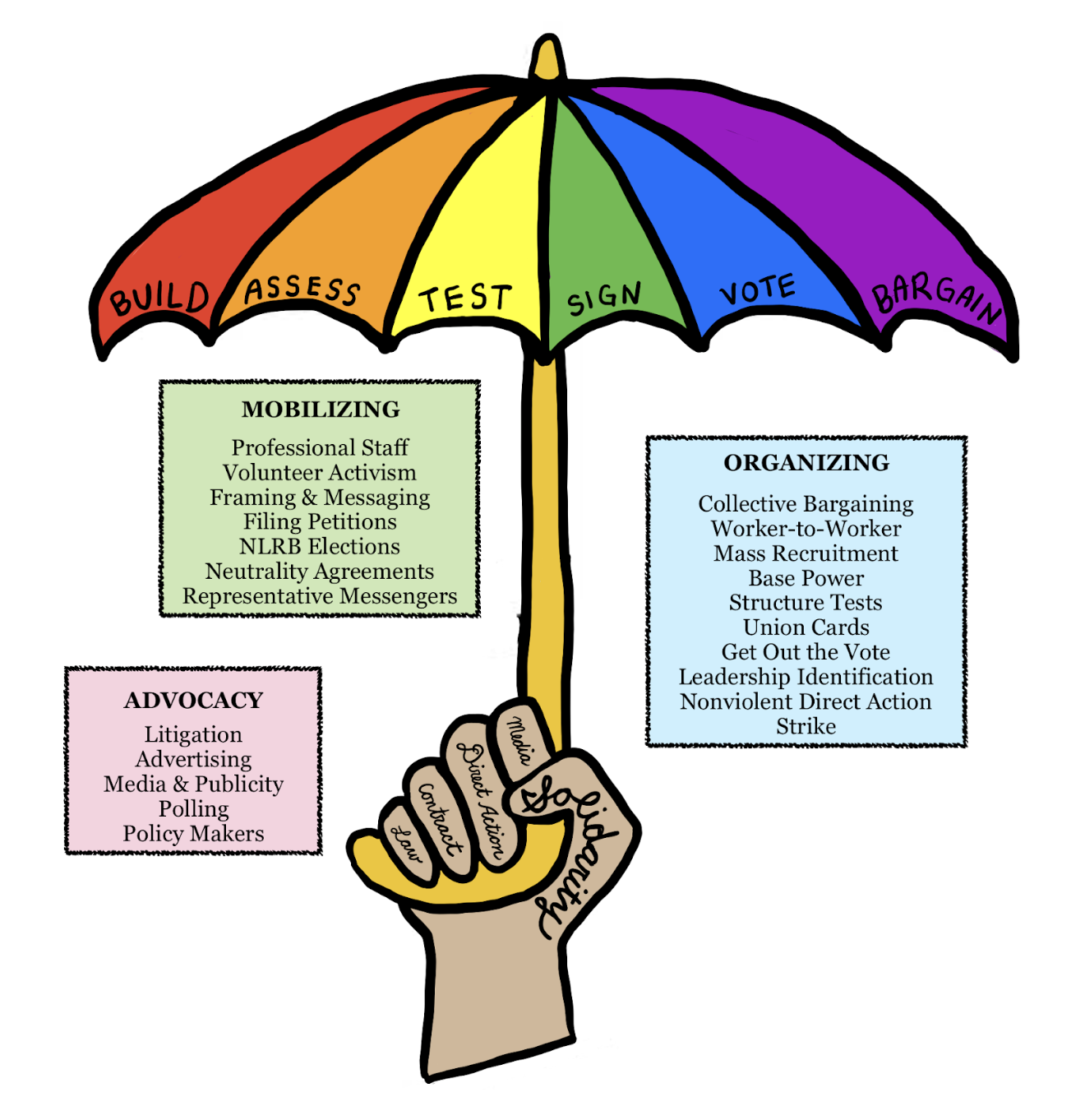

Most labor unions organize for the formation of a union and creation of a contract according to the following steps (Figure 1):

- Build a representative organizing committee (OC)

- Assess workers to build supermajority support

- Test the strength of the unit with organized actions

- Sign union authorization cards

- File for and vote in a union election

- Collectively bargain and ratify a contract

Figure 1: A raised fist, commonly used as a symbol of union power, holding up an umbrella. The umbrella represents the steps taken to form a union. The fist is detailed with sources of power for workers on each finger, as passed down through union lore: we use the media to point out issues, direct action as a way of standing up to the boss, a contract as a promise to enact change, and the law when we need to (although it is the weakest resource). Finally, the thumb represents our solidarity and is important to show proudly on the outside of a raised fist. Beneath the umbrella are different tactics used in union efforts, falling under three distinct approaches of advocacy, mobilizing, and organizing.

Labor organizations achieve these ends through different means, which are divided into three loose categories of advocacy, mobilizing, and organizing according to Jane McAlevey (Figure 1).8 Trade unions, for example, traditionally use a combination of mobilizing and organizing tactics, using professional staff to help rank-and-file members amass enough union support to file for a recognition election through the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Upon an election win, trade unions engage in formal collective bargaining with the employer(s) to obtain and ratify a first contract. Advocacy organizations, on the other hand, focus more on engaging workers in specific issues around which they can put pressure on employers and legislative bodies through petitions, demonstrations, and media. The end goal may be collective bargaining, but it is not always explicitly outlined in advocacy strategies.

For graduate workers, UAW, SEIU, AFT, and (more recently) UE follow the trade union organizing model to establish formal unions and collective bargaining agreements. The American Association of University Professors (AAUP), on the other hand, focuses on creating advocacy chapters that “provide a vehicle through which…members can collectively respond to attacks on academic freedom, shared governance, and higher education as a common good” (without explicit collective bargaining).9 While all of these organizations use most of the tactics under the umbrella (Figure 1), they tend to focus heavily on professional staffing, data analysis, advocacy around common issues, media presence, and social justice activism in their organizing campaigns. These can certainly help a campaign, but Jane McAlevey argues that such tactics among a “New Labor” movement follow a trend similar to the Democratic Party’s obsession with pollsters, and that these “shortcuts” cannot replace bottom-up, grassroots, strike-ready, rank-and-file organizing.10

What kinds of shortcuts do organizers take in graduate worker campaigns? The most common “asks” involve endorsement with little actionable followup, such as signing petitions, sending letters with demands, emailing university administrators, adding emails to list-servs, retweeting pro-union statements, calling legislators, and signing union authorization cards. These tasks are par for the course of a union campaign, but too frequently they are the emphasis rather than an addendum to organizing. Why? Frankly, it is easier to ask colleagues to sign something rather than asking them to put their livelihood at stake. Urging people to take control of their working conditions takes more time, more trust, and stronger connections. Talking to people about their struggles and how to overcome them collectively becomes harder in an increasingly digitized, atomized, polarized society. But it is not impossible to have organizing conversations that bring contradictions into the open, where one asks, “Will you join me in putting our means of living on the line to make things better for everyone?” Then one has to sit with the uncomfortable silence—what we need is more practice.

Challenges in STEM

STEM departments have been historically more difficult to organize in union campaigns compared with other academic units. This may be partially due to an intentional lack of political education in STEM fields as well as the common inclination of scientists to remain apolitical. However, I believe that union organizers take many detrimental shortcuts when approaching STEM colleagues, three of which are discussed here: (1) overemphasis on activism, which leads to leadership misidentification; (2) strike aversion; and (3) overreliance on professional staffing.

Let us first distinguish activism from organizing. For example, imagine there is a petition circulating among grad students for subsidized commuter benefits. A student signs the petition and then emails it to some colleagues, encouraging them to sign and/or post it on social media accounts. If they also choose to have one-on-one conversations with colleagues to determine what is at stake and how they can work together should their petition be ignored, this is organizing. If not, it is activism. This is not to say that activism is unimportant, but rather that the key difference between the two is “self-expression and movement building,” according to Astra Taylor.11 What happens if this petition fails to cause substantive change at the university level? Is there an organized movement ready to “build and exercise shared power,”12 or not?

When union organizers assess workers in their units, they categorize the workers according to their support, neutrality, or opposition to union organizing. It is tempting to return to supporters for further organizing although it is more important to organize those who are on the fence. Since there tends to be ambivalence and/or opposition to unions in STEM departments, it feels exciting to find a STEM colleague who proudly supports unionization. It is here that graduate students, informed by professional staffers of umbrella organizations, make a key mistake; they focus their attention on STEM students who are already “advocates for change,” unafraid to express their support, or behave more as activists.13

In focusing on activists, organizers take another shortcut; they misidentify active union supporters as leaders in STEM departments. Pro-union “leaders” then start coming to OC meetings and try to mobilize their department colleagues into doing the same. While something manifests in the short-term, it is weaker than what is necessary to build power for multi-year union campaigns that will face fervent anti-union attacks from university administrations. While it is tempting to think that “leaders” are those who come to every protest, wear their union pin proudly, and sign every petition, they are not the same as organic leaders. An organic leader is someone who has followers, who can compel others to action. Organic leaders do not have to be pro-union at the outset; what is important is how they relate to their colleagues, and whether they can build lasting worksite structures.14 By working consistently with organic leaders and seeing if they can become the agents of their own change, graduate union organizers may achieve long-lasting victory.

Another shortcut present among graduate union campaigns is strike aversion. McAlevey advocates for the use of “strike” early in the organizing process; semantics matter when articulating a theory of power.15 When I was a lead organizer in my own graduate union, I was advised by professional staffers to avoid discussing strikes too soon with my colleagues in the chemistry department, as if it would spook them. When running information sessions, we were advised to treat strikes as “the last resort option” and focus on other kinds of tactics that would be more palatable to scientists.

But how many unions have had successful elections and contract negotiations without strikes, or at least without authorized strike votes? Our power as student workers comes from our ability to leverage and withhold our labor, whether it be research, writing, teaching, service, clerical work, mentorship, or other kinds of (paid or unpaid) academic labor. Our theory of power must come from our “own ability to sustain massive disruptions to the existing order.”16 A chemistry colleague of mine once told me that if they were to go on strike, and the compounds in their lab hood were to be unmonitored for a long period of time, certain disastrous chemical reactions would take place. They did not say this to suggest that they were interested in putting others at risk, but that their labor was vital to the safety of the university, without which the university would suffer. It is a disservice to our colleagues not to acknowledge the leverage they have over our employers, and not to build this power together. Conversely, it is empowering to talk to STEM workers about striking, as it can move them to understand the power they have over the university administration.

Finally, an overreliance on professional staffing among organizations such as the UAW, SEIU, and AFT undermines the autonomy of graduate workers themselves, which hurts graduate campaigns in the long run. While these unions express that they will honor the independence of the workers, too often I have found myself in OC meetings that are facilitated by peers in name only. This means that agendas are made ahead of time, with minimal input from the workers, and given to a graduate student to “facilitate” as a way of keeping up appearances of rank-and-file democracy. This results in a culture that disengages STEM graduate students from union organizing and diminishes the effectiveness of organizing around issues that uniquely impact graduate students in STEM.

To be clear, I do not think that professional union staffers sabotage workers and union organizing; but they are trained to run campaigns according to trade union models that may not work in academic labor organizing drives, particularly in STEM. It is true that these umbrella organizations have useful expertise to share with nascent union campaigns. However, the workers themselves should decide how to run their campaign, make decisions, and define new strategies when traditional ones fail.

For example, I have seen how signing union authorization cards can both help and hinder a campaign. Sometimes, the signing is a logical conclusion to months-long conversations about how workers can build power together through a union – and sometimes it is done swiftly, and more shallowly, to keep up with weekly assessment goals set by professional staffers. Furthermore, while all PhD students are undoubtedly overworked, it is true that the structure of lab-based research in STEM departments offers little flexibility for STEM students in their schedules and lives outside of the lab. In my experience, when STEM organizers raise serious concerns about certain organizing tactics, staffers tend to dismiss them–leading to organizer burnout that threatens the longevity of the campaign. In some cases, autonomy of a local is not explicitly granted until after the election, meaning that years of pre-election organizing can be ripe with frustration and strife.

State of the Unions

Let us examine the success rates of graduate student union campaigns under different umbrellas and the ways in which union contracts benefit PhD students. At first, the number of successfully certified unions shows promise; grad workers have won union elections at both public and private institutions, especially following the 2016 NLRB decision to grant graduate students at private universities the right to unionize.17 But not all union victories have led to a ratified first-contract, because university administrations at Boston College,18 University of Chicago,19 and Yale University20 have refused to recognize their grad student unions. Others have contracts that only apply to a portion of graduate workers. For example, engineers are not included in the Tufts University unit because they are not students in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.21 Similarly, the Brandeis University graduate union includes only teaching fellows, leaving swaths of research fellows with no protections,22 and NYU’s graduate union does not cover research assistants in a variety of STEM departments.23

The bargaining processes at Columbia and Harvard led to contracts that focused on wage increases, but ultimately neither resulted in stipends that kept up with the rate of inflation or met the minimum living wage in their respective cities for the duration of the contracts. At Columbia, the new four-year contract ratified in January 2022 provides only a 3 percent annual raise (after an initial 6 percent raise given to PhD students with low stipends). Harvard’s 2021 contract saw cuts in proposed pay increases by 1.2 percent, with both the proposed and actual increases failing to keep up with the almost 7 percent rate of inflation.24 Graduate workers in both units walked away from these recent negotiations with a contract that “meets neither student-workers’ needs nor the union’s original demands.”25 While material concessions are often made during collective bargaining, these “wins” threaten the solidarity of graduate workers. For instance, the inclusion of a no-strike clause for four years at Columbia, similar to what was done at NYU, “tie[s] students’ hands in the future under conditions in which millions of workers are being radicalized and driven into struggle.”26 How strong are our fists if we cannot raise them together in a strike?

While umbrella organizations are meant to help graduate workers navigate the complex web of contract negotiations, it is interesting that, for example, the UAW has been named as one of “two hostile forces” that “[Columbia] student workers have been up against” (with the university administration being the other).27 Murtagh names them as “part of the nationalist and pro-corporate framework of the entire AFL-CIO trade union apparatus,” referencing the largest federation of unions, American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, which includes police and prison guard unions. A leaked 2018–2019 budget report showed that the AFL-CIO spent more than 35 percent on “funding political activities” and less than 10 percent on organizing.28 McAlevey clarifies that the former includes “pollsters, communicators, and polling,” which replaced the latter, namely “face-to-face organizing.”29 She even cites an interview with Peter Olney, a retired organizing director of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, in which he indicates that “the conversations [that New Labor was driving] were about how workers really got in the way of organizing.”30 Similarly, UAW presidents from Douglas Fraser (1980) to Ray Curry (2021) have described employer-employee relations as “labor-management partnerships” that are vital to “drive this nation’s economic engine,” implying that the workers’ and bosses’ interests exist on a level playing field for these unions.31 This certainly explains why graduate workers at Columbia found themselves at odds with UAW organizers; it becomes clearer with every new contract that workers are not at the center of organizing, even if organizations are touting the correct rhetoric about workers’ rights.

This is all to say that umbrella organizations’ tactical choices have serious ripple effects on graduate worker power and solidarity. While it appears that graduate student unionization is on the rise, pre-election campaigns at Princeton University, University of Pennsylvania, Duke University, Northeastern University, BU, and others have hit points of stagnation. Some employers, like Princeton, have voluntarily raised graduate wages in response to Columbia’s wage increases;32 they respond more to competition with fellow Ivy League institutions than to workers demanding basic living wages. This is a great example of how much money and power an elite university administration wields, as they can easily increase wages at will. Some graduate workers, such as those at BU, have chosen to disaffiliate from the UAW and find new partnerships, as strategic disagreements between rank-and-file graduate organizers and paid staff organizers led to tension and strife that brought organizing to a temporary halt. What is lacking from some of these campaigns is a commitment to deep organizing, meaning that parent unions are quick to take shortcuts for swift victories that undermine the longevity of the academic labor movement. We know that a deep commitment to organizing and sustained movements driven by workers can bring about meaningful victories; what happens in the absence of such a commitment?

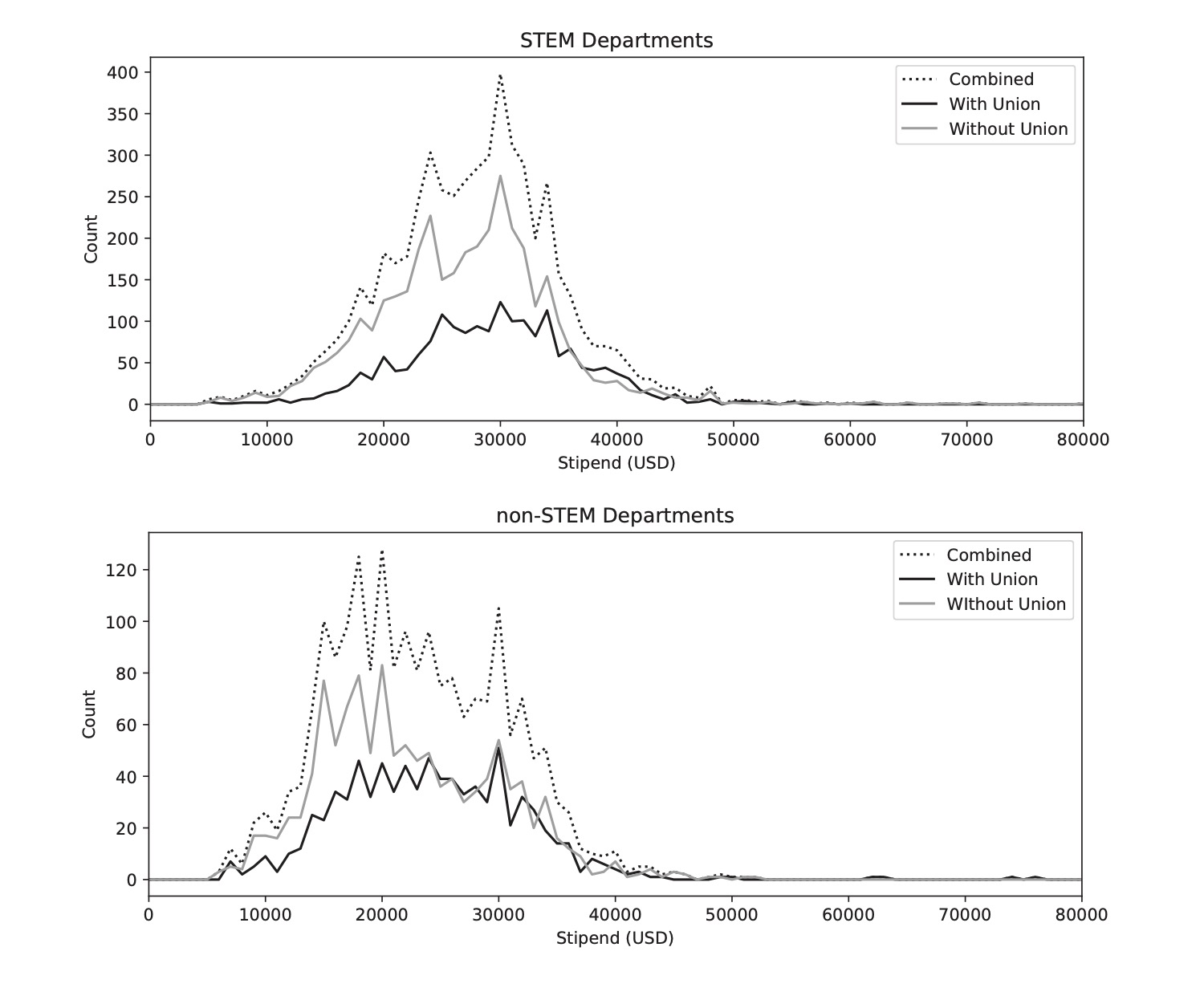

How successful are unions at improving the working conditions of graduate students? Let us look at the most rudimentary measure of economic well-being of graduate students: the stipends they receive. Some are compensated directly by the university in exchange for teaching service for 8–10 months; the tendency for students in the humanities to receive lower stipends is mostly due to lack of summer funding, as there are fewer classes to teach in the summer. Others, more commonly STEM PhD students, are paid to conduct research via external grants from organizations such as the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. Most research grants are paid for on an annual basis, so STEM students tend to earn more annually than their counterparts in the humanities.33

A survey of the available (self-reported) data on PhD stipends shows that while there are still more graduate programs without unions than with unions in all academic disciplines, there is a non-negligible effect of unionization on stipend increase (Figure 2).34 This effect, however, is more pronounced in non-STEM departments than in STEM departments. The median stipend shifts by $2,500 for the former and $2,300 for the latter when comparing graduate programs with and without unions. From these limited data, unionization appears to increase graduate stipends overall, however less for STEM than for non-STEM departments, interestingly. This difference may be due to initial higher stipends for STEM graduate students, although a more rigorous analysis is needed.

Figure 2: Histograms of self-reported annual PhD stipends among STEM departments (top, including Biology, Chemistry, Physics, Engineering, Math, Computer Science, Neuroscience, Statistics, Genetics, and Medicine) and non-STEM departments (bottom, including English, History, Philosophy, Sociology, Music, Art, Education, Literature, French, German, Spanish, Political Science, Anthropology). See: https://github.com/sftpmag/labor_aso/tree/master/karnaukh

What does this mean for STEM graduate workers? My point here is not to reinforce an anti-union talking point that unionization does not increase stipends substantially. Instead, I ask how successful graduate unions are at raising wages under the current organizing conditions. STEM workers tend to earn more than their non-STEM counterparts; however, the effect of unionization seems to be complicated by the particularities of the institution. My (untested) hypothesis is that stipend increases depend more on how much money and power a university administration (such as Princeton, Harvard, Columbia) wields rather than on how much power graduate workers, organizing under the umbrellas of larger labor organizations, wield. If so, then how can we organize more effectively to build more power over our employers?

A Way Forward

A union is only as strong as its base of rank-and-file members, no matter how many professional staff are added to an election or contract campaign. While the structure of conducting PhD research and teaching can lead to isolation, STEM graduate workers have a unique advantage in building this base; they have relationships to each other through experimental labs and computational groups. Scientific research also tends to cross lab groups, departments, and STEM disciplines, as many experimentalists now collaborate with theorists and/or engineers. Some graduate students find themselves housed in multiple departments, which can feel lonely, but can be a source of organizing power. To build this power, we need to learn how to better communicate face-to-face, discern what moves us to action, and learn how to find organic leaders in our departments.

One labor organization that has moved into the graduate union scene prioritizes worker power, namely the United Electrical Workers (UE). MIT graduate students, in affiliation with UE, voted 66 percent in favor of unionization in April 2022. Having interviewed UE organizers when I organized in my own unit at BU, I can speak to UE’s strong focus on rank-and-file organizing. I hope to see their clear strategy, undistracted by polling, media, and concession-making, lead more graduate workers to victory—not just a recognized graduate union or a ratified first contract, but strong, powerful unions of graduate workers. UE’s emphasis on workers setting their own priorities and building their own power confirms that there are no shortcuts.

No matter what organization we may be affiliated with, no matter what professional staffers are deciding, we have to do this work ourselves. We, as the workers, have the leverage, and we must build the power—we run labs; we shape young minds; we monitor cultures and reagents; we act as safety coordinators; we bring in millions of dollars in research grants; we build prestige for our institutions; we organize conferences that help universities bring in new scholars and new ideas; and we are an indomitable force to be reckoned with—if we are organized. Perhaps it is time to come out from under the umbrella and face the rain ourselves.

Back to Contents

Notes

- Sam Lemonick, “Who Pays When a Graduate Student Gets Hurt?,” C&EN Global Enterprise 98, no. 42 (November 2, 2020): 27–31, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cen-09842-cover.

- Meredith Wadman, “Disturbing Allegations of Sexual Harassment in Antarctica Leveled at Noted Scientist,” Science, October 6, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq1428.

- Zachary Eldredge and Coleen Baulitz, “#UsToo: How Unions Could Fight Harassment in STEM,” Science for the People 22, no. 1 (2019), https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/vol22-1/ustoo-how-unions-could-fight-harassment-in-stem/.

- Vid Mohan-Ram, “NYU Grads Win Vote to Unionize Amid Controversy,” Science, November 10, 2000, https://www.science.org/content/article/nyu-grads-win-vote-unionize-amid-controversy; Elizabeth A. Harris, “Columbia Graduate Students Vote Overwhelmingly to Unionize,” The New York Times, December 10, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/09/nyregion/columbia-graduate-students-union-vote.html; “GEO History,” Graduate Employees’ Organization, https://www.geo3550.org/about/history/; Danielle Douglas-Gabriel, “Harvard Graduate Students Vote to Form a Union,” The Washington Post, April 20, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2018/04/20/harvard-graduate-students-vote-to-form-a-union/.

- “Labor Unions,” Gallup, https://news.gallup.com/poll/12751/labor-unions.aspx; Ailsa Chang, Brianna Scott, and Lee Hale, “Public Opinion On Labor Unions Has Remained High For Decades,” NPR, April 14, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/04/14/987372006/public-opinion-on-labor-unions-has-remained-high-for-decades; Chris Maisano, “Labor Union Membership Has Just Hit an All-Time Low. We Need to Reverse This Trend,” Jacobin, January 23, 2020, https://jacobinmag.com/2020/01/labor-union-membership-density-bls-2019; “Union Membership Hits All-Time Low,” MacIverNews, January 31, 2022, https://www.maciverinstitute.com/2022/01/union-membership-hits-all-time-low/; Doug Henwood, “Union Membership Is Still Declining,” Jacobin, January 25, 2022, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2022/01/labor-density-historical-comparison-strikes-weakness.

- Joe Maniscalco, “How Can the Bosses Be ‘neutral’ When They’re Spending $340 Million on Union-Busting Lawyers?,” LaborPress, December 12, 2019, https://www.laborpress.org/the-bosses-cant-be-neutral-when-theyre-spending-340-million-on-union-busting-lawyers/.

- Eli Rosenberg, “Workers Are Fired Up. But Union Participation Is Still on the Decline, New Statistics Show,” The Washington Post, January 23, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/01/22/workers-are-fired-up-union-participation-is-still-decline-new-statistics-show/.

- Jane F. McAlevey, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age (Oxford University Press, 2016).

- Chelsea Fowler, “New AAUP Advocacy Chapters,” AAUP, February 5, 2019, https://www.aaup.org/article/new-aaup-advocacy-chapters-0.

- McAlevey, No Shortcuts.

- Astra Taylor, “Against Activism,” The Baffler, no. 30 (2016): 123–131, https://thebaffler.com/salvos/against-activism.

- Taylor, “Against Activism.”

- Taylor, “Against Activism.”

- McAlevey, No Shortcuts.

- McAlevey, No Shortcuts, 88.

- McAlevey, No Shortcuts, 8–9.

- “Student Employee Union Growth,” Washington University and Undergraduate and Graduate Workers Union, accessed August 1, 2022, https://wugwu.shinyapps.io/union_map/.

- Karen Anderson, “Boston College Grad Student Workers to Rally for Rights, Protections,” WCVB, March 10, 2020, https://www.wcvb.com/article/boston-college-graduate-student-workers-to-rally-for-rights-protections-threatening-strike/31301055#

- Nikhil Jaiswal, “Looking Back and Forward: GSU’s Fight for Graduate Student Rights and Recognition,” Chicago Maroon, April 27, 2021, https://thechicagomaroon.com/28471/news/looking-back-forward-gsus-fight-graduate-student-rights/

- Megan Vaz, “Hundreds Rally for Yale to Recognize Graduate Student Union,” Yale Daily News, May 7, 2022, https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2022/04/28/hundreds-rally-for-yale-to-recognize-graduate-student-union/

- Jessica Blough, “Arts and Sciences Graduate Students Ratify First Contract in Unanimous Vote,” The Tufts Daily, October 22, 2018, https://tuftsdaily.com/news/2018/10/22/arts-sciences-graduate-students-ratify-first-contract-unanimous-vote-2/.

- Colleen Flaherty, “Brandeis Grad Students Win Significant Gains in Union Contract, Even as Trump Administration Has Exerted Influence on NLRB,” Inside Higher Ed, September 5, 2018, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/09/05/brandeis-grad-students-win-significant-gains-union-contract-even-trump.

- “Understand Our Contract,” GSOC-UAW Local 2110 | The Union for Graduate Employees at New York University, https://makingabetternyu.org/understand-it/.

- Elliott Murtagh, “Columbia Student Workers Ratify Contract with Cuts in Real Wages: The Political Lessons,” World Socialist Web Site, February 7, 2022, https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2022/02/08/colu-f08.html; Josh Varlin, “Harvard Graduate Student Union Pushes through Contract with Cut in Real Wages,” World Socialist Web Site, December 1, 2021, https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2021/12/01/hgsu-d01.html.

- Varlin, “Harvard Graduate Student Union Pushes through Contract.”

- Murtagh, “Columbia Student Workers Ratify Contract.”

- Murtagh, “Columbia Student Workers Ratify Contract.”

- Hamilton Nolan, “AFL-CIO Budget Is a Stark Illustration of the Decline of Organizing,” Splinter, May 16, 2019, https://splinternews.com/afl-cio-budget-is-a-stark-illustration-of-the-decline-o-1834793722.

- Jane McAlevey, “Put Workers Back at the Center of Organizing,” New Labor Forum 25, no. 3 (2016): 87–89, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26420016.

- McAlevey, “Put Workers Back at the Center of Organizing.”

- Murtagh, “Columbia Student Workers Ratify Contract”; Jerry White, “UAW President Hails ‘Labor-Management’ Partnership Following Sellout of Volvo Strike,” World Socialist Web Site, July 21, 2021, https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2021/07/22/curr-j22.html.

- Julie Bonette, “Princeton Increases Graduate Student Stipends by 25 Percent .” Princeton Alumni Weekly, The Trustees of Princeton University, March 2022, https://paw.princeton.edu/article/princeton-increases-graduate-student-stipends-25-percent

- Ben Cohen, “The True Cost of a Phd: Giving up a Family for Academia.” The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, 7 Jan. 2020, https://www.jamesgmartin.center/2019/10/the-true-cost-of-a-phd-giving-up-a-family-for-academia/

- From PhDStipends.com, a database created by Dr. Emily Roberts of Personal Finance for PhDs.