March 1, 2021

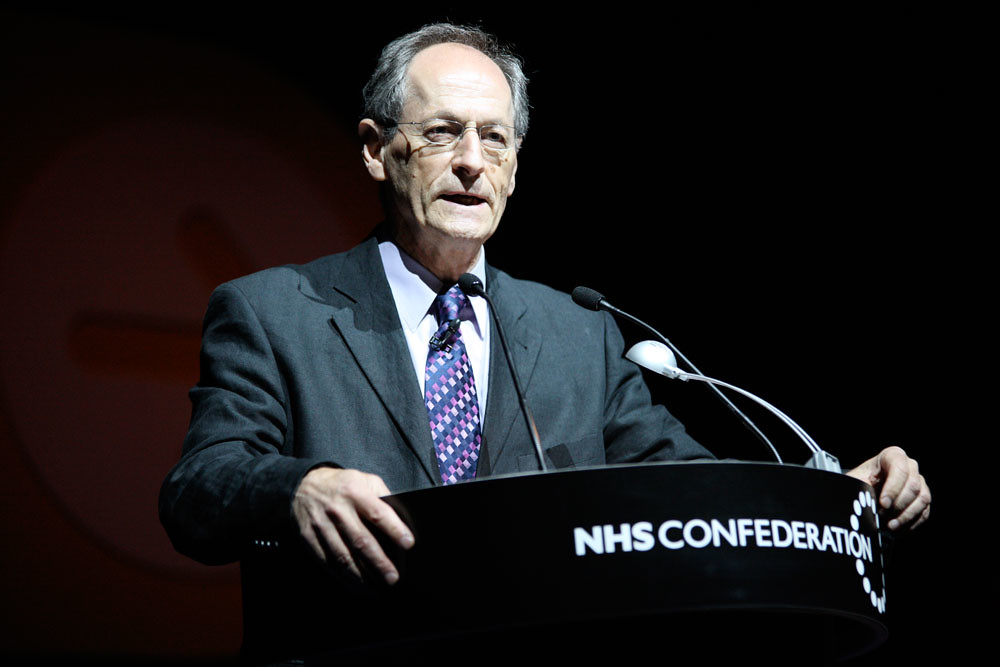

Climate Change, COVID-19, and Austerity: A Discussion with Michael Marmot

By Søren Hough

I first heard Professor Sir Michael Marmot speak at a Students for Global Health event at the University of Cambridge. He described how life expectancy is no longer increasing in the UK and the US, and that it is in fact declining for women living in poverty.1 This isn’t due to a natural biological plateau in life-expectancy: other countries like Spain have higher life expectancies than the United Kingdom and still see yearly increases.2

Professor Sir Marmot attributes this phenomenon at least in part to “deaths of despair” (drugs, alcohol abuse, and suicide), racism, and inequities in social determinants of health.3 He has further called for strategies to combat systemic racism and engage in decolonial efforts to address some of these issues.4 In the United Kingdom, the data similarly point to deaths of despair and social determinants as a root cause of life expectancy stagnation.5 Professor Sir Marmot has indicated government austerity is the root cause of flatlining life expectancy and increased health inequality.6

It should be noted that COVID-19 exacerbated life expectancy stagnation. Life expectancy in the US dropped by one year in the first six months of 2020. Once again, we see the consequences of racism in healthcare: Black Americans saw a three year reduction over the same time period.7

I sat down with Professor Sir Marmot on behalf of Science for the People in August 2020 to discuss the social and environmental factors that play into public health, how those factors tie into race and socioeconomic status, and how we can improve wellbeing through social and policy-based change.

Søren Hough: You’ve been working in the public health world for some time. Over the course of your career, how has climate change become a more prominent issue and even intersected with your field?

Michael Marmot: In my research, I had not spent much effort looking at environmental issues. There were people who were working on air pollution — good, but that wasn’t what I was doing. I was much more interested in the social environment. When I chaired the World Health Organization (WHO) commission on social determinants of health from 2005–2008, I wrote around that time and I commented that there was a “planet-sized hole” in my book, Status Syndrome. I wasn’t defending the fact that I hadn’t done it. Status Syndrome was, in a sense, a report of the work I’d been doing the previous twenty-five years. And that hadn’t focused on the planet or the environment.

When I chaired the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, we still didn’t deal with climate change, but we said we should. What we said then was that the agenda on social determinants of health and health equity and dealing with climate change had to take place at the same time because dealing with climate change would mean a radical change in the way we addressed the issues.

I then chaired a series of commissions. We did the English review, known as the Marmot Review, in 2010, and again, we said this: we need to deal with them at the same time, without quite explaining what the climate side of the action needed to be. I then chaired the European Review of Social Determinants and the Health Divide, and again said it.8 In the Pan American Health Organization of Health report, which we published last October, we did get a bit further. We talk about climate and the environment as being one of the structural drivers and we talked about its importance. We gave the example in Central America, in Costa Rica, where more than 95 percent of energy is renewable.9 So we did get a bit more explicit. We’re getting closer.

In my review, “The Marmot Review 10 Years On,” we had some explicit recommendations about how housing should contribute to [carbon] neutrality and net zero greenhouse gas emissions.10 Currently, I am chairing a subgroup for the government’s Climate Change Committee on health.11 And because I was asked to do it, I changed “health” to “health equity.” (If they didn’t want to focus on health equity, they should have asked someone else to do it!)

This report is explicitly now trying to deal with net zero greenhouse gas emissions and health equity. What I’ve described to you is I hope progress, going from a planet-sized hole in my book, Status Syndrome, published in 2004, to chairing a subcommittee report that explicitly links net zero greenhouse gas emissions with health equity.

SH: There are two ways to consider the issue: public health research considering climate change, and climate change research considering public health. Considering the proposed governmental initiatives to address climate change, such as the Green New Deal, to what extent do you think they need to take public health and social determinants into consideration?

MM: Take active transport. That’s sort of an easy one, isn’t it? Active transport means you use the car less, and so there would be less air pollution. Air pollution by itself is not contributing to climate change, but greenhouse gas emissions are, and air pollution tends to go along with it. If you have more active transport — walking, cycling, and public transport, which also engages some degree of walking — that will be good for health, potentially good for health equity, and good for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Similarly, reducing meat consumption. Now, on the scale things, transport is a much more important contributor to greenhouse gases than agriculture and eating meat, so you make less of a contribution. But still, reducing meat consumption, increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables, legumes, nuts, and seeds, is likely to be good for health and is likely to be good for the planet. You said rightly there are two ways of looking at it. I think it’s important to look both ways.

SH: On the issue of behavior, domestic actions can impact the international community. There’s an imbalance between the Global North and South in terms of who is contributing to climate change and who is feeling the brunt of the effects of climate change. Can countries in the Global North continue to consume at the current rate while meeting the demands of combating climate change, and what does that mean for climate justice?

MM: I talk about social justice and health having two dimensions: the inequities within countries and the inequities between countries. I think climate justice means the same — the inequities within and between countries. In the United Kingdom, there’s a levy that households pay on their energy bills that goes toward renewable energy. That’s regressive, that levy. It’s regressive. If it was properly tax-based, and we had a properly progressive taxation system, it wouldn’t be regressive.12 We need to be thinking about equity within countries.

And like I said, it’s not just effects of climate change, but the equity effects of mitigation and adaptation that are important, as well. A consumption tax, in general, is regressive; an income tax is less regressive. I’m not against taxation as a mechanism to promote change, but we do need to bear in mind the distributional effects.

The bushfires in Australia, the forest fires in California, are something of a wake-up call, saying, “Hang on, we don’t just want you to do this to look after people in the Global South. We don’t want you just to be good people, although we’d quite like you to be good people. The world would be a better place if more people took a global view to the planet. But you need to do it in your own self-interest, too.” Those bushfires in Australia, the fact that you and I are sitting here in 30oC [86°F] temperature — we know that weather and climate are not the same thing, but we also know that the majority of the hottest years on record have come in the last few years. Today’s 30oC temperature might not be related to climate change, but the fact that the hottest years on record have all come more recently… It’s becoming increasingly clear that the Global North has to preserve itself, not just in the interest of the Global South.

I would love it if we could act in a responsible way for the planet. Failing that, let’s act in our own self-interest, which means acting to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in a climate-responsible way. I’ve been talking about social justice and health, and I think it has to go along with climate justice.

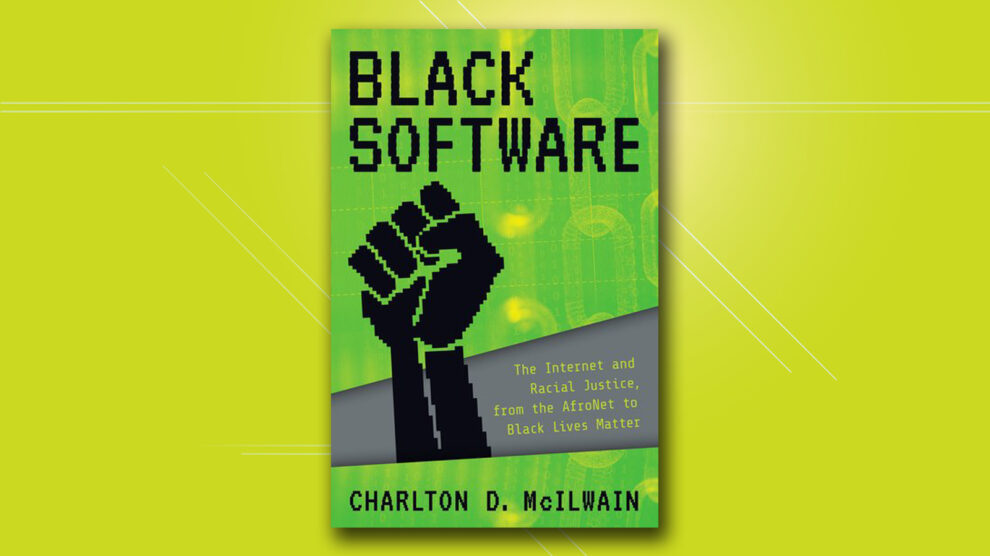

SH: I’d like to turn to public health in the context of disease and the COVID-19 pandemic. There’s been a longstanding trend of trying to provide “technofixes,” like CRISPR, to public health crises rather than focusing on social factors.13 How does this trend manifest in international efforts and domestic policy, and what are your thoughts on that kind of approach to public health?

MM: It’s a good question. I was confronted by exactly that before I got involved with the WHO commission on social determinants and I was doing much more research. I showed an American colleague the gradient in health from the Whitehall Studies: the lower the grade of employment, the higher the risk of illness. He said, “Wow, there must be a chemical — we could get a chemical and inject it. Because you’ve got a dose response relation. There’s something about being lower in the hierarchy, so we’ll just figure out what it is. Maybe it’s something to do with the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis, so we’ll regulate the HPA axis and we’ll get rid of inequalities in health!”

It’s a point of view. I said, “Well, maybe, but do you think that’ll change the social gradient in depression?” He said, “We’ll fix the chemical that leads to the social gradient in depression. We’ll get the chemical that leads to the social gradient in heart disease, and the chemical that…” And on we go. I’m not against that! I mean, if a chemical solution leads to better health for the population. I’m all in favor of better health for the population.

That said, what I’m arguing is that the inequalities in the health of the population are telling us something fundamental about how well that population is meeting its society’s needs. If health is not improving and health inequalities are increasing, it’s not because they’re lacking a particular chemical. It’s because society has stopped meeting people’s needs properly.

So if a biochemical, a CRISPR solution, leads to less morbidity and mortality, great. But it won’t solve the problem of people’s needs not being met.

SH: A lot of these international groups and organizations are invested in these kinds of technofixes. If we go all the way back to the Rockefellers, they were very interested in these kinds of approaches. That does influence how these kinds of policies are approached.

MM: Bill Gates has said the same thing. They’ve been quite explicit about it — they want to find vaccines and chemical treatments and the like with their resources and their good will. I think they do have good will. They’ll make a contribution. I’d like them to address the social determinants of health, as well.

SH: Even in that case, there’s a question of accountability. If our government is making decisions, we have the ability to vote and exercise at least some oversight over decision making (of course, countries affected by US decision making don’t get a vote). But with private foundations and groups, there’s even less oversight in terms of directing projects toward social justice and social determinants.14

MM: It seems to me the philanthropy-based model has that drawback. I wrote a review in The Lancet of a book by Anand Giridharadas, Winners Take All, which — if you read my review — you can see I was enthused about. And another one, The Business of Changing the World, which I’ve already forgotten, I was less enthused about.15 The Business says look, these philanthropists are wonderful people, and they’re disruptive, and they’re bringing their insights in how to run the world of business to philanthropy and they’ll improve the world.

Giridharadas said, we’ve got a system where these people got incredible riches and what they are arguing is, “Don’t change the system.” Let’s let them continue to accumulate these incredible riches. And since they’re obviously such wonderful people because they wouldn’t have gotten rich if they weren’t wonderful, then, out of the goodness of their hearts, they can decide how to solve the world’s problems. I think it is a model that’s problematic, and that was Giridharadas’s point. I thought his book was terrific.

SH: That’s exactly what I was getting at. It’s valuable to go back all the way to Andrew Carnegie’s “The Gospel of Wealth” where he argues it’s better for the rich to control society than the unwashed masses — that they should be “trustees of the poor.”16

MM: Giridharadas, if I remember, quotes from Carnegie’s essay.

SH: I wanted to ask you about the impact of the pandemic and lockdown on poorer communities, particularly as it relates to the ability to social distance, access resources like masks, working on the front line, and other factors.

MM: What I summarized in my Guardian opinion piece was that the inequalities in mortality more generally look pretty parallel with the inequalities in mortality from COVID-19. If you classify areas by degree of deprivation — the more deprived the area, the higher the mortality from all causes, and the higher the mortality from COVID-19. In other words, the causes of health inequalities more generally, the things that I’ve been writing about for a long time, relate to the causes of inequalities in COVID-19.

That said, there is some excess of COVID-19 in the most deprived areas. I think that relates to the things you just mentioned: overcrowding, employment in frontline occupations… And, one big difference, is the high mortality in Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic groups (BAME), which can be attributed to deprivation and what we just said: overcrowded accommodation, employment in frontline occupations, and/or losing your job and worsening economic fortunes.

I quoted Albert Camus in my article. Camus said, “The pestilence is at once blight and revelation. It brings the hidden truth of a corrupt world to the surface.” I’ve been saying: COVID-19 exposes the inequalities of society and amplifies them.

SH: And taking that further, I’m keen to hear your thoughts on how this has impacted those in prison.

MM: There’s I think quite good evidence, less so from the United Kingdom, that prisons are a hotbed for COVID-19.17 It’s a real worry. We’ve written about mass incarceration as a means of social control.18 I think just as we’re seeing COVID-19 increasingly following the social gradient and very high at the bottom — so, predictably, it’s high in prisons.19

SH: I’m sure you’ve been following the protests in the United States around the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Many involved in those uprisings, particularly abolitionists, have called on cities and towns to defund the police and reduce the prison population. There’s been a lot of discussion on the political side of things as to whether police and prisons even reduce crime, but beyond that, I wanted to ask for your thoughts on whether defunding and reallocating police funds to social programs might improve health outcomes.

MM: In “Marmot Review: 10 Years On,” we’ve got figures for the rise in violent crime. The more deprived the area, the greater the violent crime and the bigger the increase over time. Well, I look at that and think, it’s not such a surprise, you know? If you close Sure Start Children’s Centres, if you increase child poverty, if you reduce funding for schools, if you abolish the education maintenance allowance which helps youngsters from deprived backgrounds stay in school, if you reduce the funding to local government so they close facilities for adolescents and young people, guess what? They get involved in gangs and violent crime and knife crime. It’s utterly predictable. Spending some of that money on prevention and creating healthier communities would be a good thing to do.

SH: There were actually three studies conducted in Pennsylvania that showed that greening spaces — mowing lawns, fixing broken windows, and so on — dramatically reduced gun crime in the neighborhood.20 And it didn’t displace the gun crime to a nearby neighborhood, either; it was just reduced full stop. If something so basic can reduce crime, it seems to me investing in those programs is far more useful than giving money to the police under the assumption crime is inevitable.

MM: Why would you start with the proposition that a youngster is evil and that he’s going to kill somebody else and himself because he’s evil?21 Why not start with the proposition that he’s fallen into a gang and gotten involved in drug dealing because he had little other economic possibility? If you could deal with all of those things, that youngster is less likely to be involved in violent crime.

I had a meeting with a group in Victoria (Australia) of Aboriginal leaders, VACCHO: Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. They’re all Aboriginal leaders of community controlled health organizations around the state. I said to them that my understanding is that the default position of the child services in Australia is that Aboriginal parents are incompetent. The question is not will you remove the child from the family, but when. That has disastrous consequences for the child and the family.

And then I said, my understanding is it costs $100,000 AUD a year, or some ridiculous figure, to look after a child in care with all of the people involved. Nobody thinks it’s a good idea that a child should stay unsupervised with an abusive parent. No one thinks that’s a good idea. But for a $100,000 AUD a year, couldn’t you actually work with the families and try and deal with their problems of drug abuse and alcohol and violence to try and keep the child with their family?

One leader said, “We’re doing that in Ballarat. We’ve taken on formal responsibility for the children and we get funding to work with the families to try and keep the families together.” Now, we weren’t talking about crime then, but we know the incarceration for Indigenous Australians is huge. It’s twelve times, fourteen times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians. Part of that is racism in the police, part of that is these kids are getting into trouble, and they’re getting into trouble because of their early life history, either being in abusive families or getting taken into care, which is not a panacea. Spend that money and try to deal with these kids’ early life and try to keep them out of prison.

When I went to Alice Springs in the Northern Territory of Australia, the biggest building by far was not the hospital — it was the courthouse. It looms over the rest of Alice Springs.

I thought, what a statement.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

—

Søren Hough is a PhD candidate in the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Cambridge. He uses CRISPR in his day-to-day research studying the mechanisms of DNA repair. Søren also works as a freelance journalist and has covered everything from film and television to science, ethics, and politics. When he’s not in the lab or writing, he organizes with local groups to effect equitable and just societal change.

Notes

- “Life Expectancy Not Improving for First Time in 100 Years,” UCL News, February 25, 2020, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2020/feb/life-expectancy-not-improving-first-time-100-years; Max Ehrenfreund, “The Stunning — and Expanding — Gap in Life Expectancy Between the Rich and the Poor,” The Washington Post, September 18, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/09/18/the-government-is-spending-more-to-help-rich-seniors-than-poor-ones/.

- “Chapter 4: European Comparisons — Life Expectancy in the UK, England and Other EU Countries,” Public Health England, July 13, 2017, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-profile-for-england/chapter-4-european-comparisons#life-expectancy-in-the-uk-england-and-other-eu-countries.

- Michael Marmot et al., “Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On,” Institute of Health Equity (February 2020): 27, http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/marmot-review-10-years-on/the-marmot-review-10-years-on-full-report.pdf.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud, “Just Societies: Health Equity and Dignified Lives. Executive Summary of the Report of the Commission of the Pan American Health Organization on Equity and Health Inequalities in the Americas,” PAHO (2018): 31, https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/49505.

- Marmot, “Health Equity.”

- Marmot, “Health Equity,” 5.

- Laura Santhanam, “COVID-19 Has Already Cut U.S. Life Expectancy by a Year. For Black Americans, It’s Worse,” PBS, February 18, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/covid-19-has-already-cut-u-s-life-expectancy-by-a-year-for-black-americans-its-worse.

- Michael Marmot et al., “Review of Social Determinants and the Health Divide in the WHO European Region: Final Report,” UCL Institute of Health Equity, https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/251878/Review-of-social-determinants-and-the-health-divide-in-the-WHO-European-Region-FINAL-REPORT.pdf.

- Organización, “Just Societies.”

- Marmot, “Health Equity.”

- “Sustainable Health Equity: Achieving a Net Zero UK (UCL),” Climate Change Committee, November 6, 2020, https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/ucl-sustainable-health-equity-achieving-a-net-zero-uk/.

- “Why is Inequality Increasing? Because the Rich Aren’t Paying Their Way,” Rethinking Poverty, February 5, 2019, https://www.rethinkingpoverty.org.uk/talking-points/talking-points-january-2019/.

- Michael Barker, “On Corporate Power Rockefeller’s Medicine Men,” Ceasefire, February 20, 2011, https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/corporate-power-2/; James Meek, “The Health Transformation Army,” The London Review of Books, July 2, 2020, https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v42/n13/james-meek/the-health-transformation-army.

- Jay Hancock, “They Pledged to Donate Rights to Their COVID Vaccine, Then Sold Them to Pharma,” Kaiser Health News, August 25, 2020, https://khn.org/news/rather-than-give-away-its-covid-vaccine-oxford-makes-a-deal-with-drugmaker/.

- Michael Marmot, “Winners Take All,” The Lancet 394, no. 10201 (September 2019): 7-13, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32035-5.

- Andrew Carnegie, “The Gospel of Wealth,” 1889, https://production-carnegie.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ab/c9/abc9fb4b-dc86-4ce8-ae31-a983b9a326ed/ccny_essay_1889_thegospelofwealth.pdf.

- Kelly Davis, “Coronavirus in Jails and Prisons,” The Appeal, October 26, 2020, https://theappeal.org/coronavirus-in-jails-and-prisons-70/; Jonathan Metzer, “Are ‘Squalid’ Prison Conditions and the Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic Breaching Human Rights?” UK Human Rights Blog, July 6, 2020, https://ukhumanrightsblog.com/2020/07/06/are-squalid-prison-conditions-and-the-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-breaching-human-rights/.

- Elias Nosrati et al., “Economic Decline, Incarceration, and Mortality from Drug Use Disorders in the USA Between 1983 and 2014: An Observational Analysis,” The Lancet 4, no. 7 (July 2019): E326-333, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30104-5.

- Elias Nosrati et al., “The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy Revisited: Deindustrialization, Incarceration and the Widening Health Gap,” International Journal of Epidemiology 47, no. 3 (November 2017): 720–730, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx243.

- Ruth Moyer et al., “Effect of Remediating Blighted Vacant Land on Shootings: A Citywide Cluster Randomized Trial,” American Journal of Public Health 109, no. 1 (January 1, 2019): 140-144, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304752; Charles C. Branas et al., “Urban Blight Remediation as a Cost-Beneficial Solution to Firearm Violence,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 12 (December 1, 2016): 2158-2164, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303434; Charles C. Branas et al., “Citywide Cluster Randomized Trial to Restore Blighted Vacant Land and Its Effects on Violence, Crime, and Fear,” PNAS 115, no. 12 (February 26, 2018): 2946-2951https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1718503115.

- Carroll Bogert and Lynnell Hancock, “‘Superpredator’: The Media Myth That Demonized a Generation of Black Youth,” The Marshall Project, November 20, 2020, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/11/20/superpredator-the-media-myth-that-demonized-a-generation-of-black-youth.