Old Contradictions and New Possibilities in Marxist and Indigenous Praxis

By Kavita Philip and Sigrid Schmalzer

Volume 26, no. 2: Ways of Knowing

At the 2017 March for Science in Washington, DC, Dr. Lydia Jennings wore a T-shirt that read, “Strong Resilient Indigenous,” and held a sign saying, “Traditional Ecological Knowledge Is Science Too!” In the sign’s margins were myriad examples, including wildlife managers, hydrologists, physicians, engineers, food sovereignty, and land care practices. Many of these categories are mainstream scientific fields; other phrases, like sovereignty and care, introduce political and cultural values into scientific practice. Taken together, they are TEK. Jennings (@1NativeSoilNerd) tweeted the photo with the hashtags #TEK and #NativesinSTEM.1 She neither relegated her Indigenous heritage to “culture” or “private belief” nor displaced her scientific credentials above or below her embodied identity. She mixed knowledge about the natural and physical worlds with social relations and political action. The sign, the embodied person, her professional practice, and her political messaging together express an entangled cultural, political, historically embedded practice and epistemology that is captured in the term “Indigenous science.”

Yet, many scientists who united against Trump could not quite find common ground with Indigenous scientists. Some critics suggested that a pluralization of our understanding of science would undermine its authority. Others suggested that Indigenous knowledge would be more respected if placed in the realm of spiritual culture rather than of scientific practice. Three Indigenous-allied scientists reflected in Bang et al. (2018), “To these critics, there is only one science, which is defined by a scientific method assumed to be transparent and objective and which produces data replicable by other scientists.” 2

As Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars have convincingly demonstrated, this positivist perspective on the universal character of scientific knowledge rests on ahistorical notions of the scientific method as a guarantor of truth, tangled up with Eurocentric historical assumptions that place scientific thinking solely in the realm of “western” thought. Western science has for centuries absorbed, borrowed, and stolen knowledge from people around the world, while disavowing the cultural contexts in which knowledge emerges and takes form. These errors have not been limited to liberal scientists; rather, a faith in the liberatory potential of universal scientific knowledge was a staple of Marxist philosophy and praxis through much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Thus, while we celebrate the growing popularity of science-based thinking in a progressive anti-Trump wave in the US, as well as a strong left-scientific global wave of anti-fascism and anti-capitalism, we insist on the necessity to confront the troubled legacy of leftist understandings of Indigenous and other traditional forms of knowledge.

Leftist movements in earlier generations explicitly sought to use science to overthrow religious ideologies that reflected and reinforced classist and patriarchal social structures. Such materialist praxis can serve liberatory purposes, and, indeed, as we discuss below, we see class-based analysis as essential in combating the new forms of primary accumulation that are perpetuating extractivist capitalism around the globe. At the same time, we argue that scientism and mysticism are two sides of the same coin: both imagine a transcendental form of thought that floats above the realm of praxis. We hold, with critical historians of science and scholars in Science and Technology Studies (STS), that “all knowledge, including scientific knowledge, is specific to its particular cultural context.”3 Both scientific and spiritual practice are embedded in history, functioning within a variety of relations (including power structures and hierarchies) that are elided when they are reified. We draw inspiration from Richard Levins, Marxist biologist and member of the original Science for the People, who recognized the necessity of maintaining a critical understanding, rooted in historical materialism, of both scientism and mysticism. 4

We are non-Indigenous social/cultural historians of science engaged with leftist critical histories of science and attentive to global histories of Indigeneity. We believe that new alliances and solidarities, vitally necessary in a new age of rising nationalisms, require a robust accounting of our historical differences. We take inspiration from new forms of praxis emerging from Indigenous communities around the world who center land and labor, and we call on left science critics to build common ground by releasing some of our reified stereotypes of Indigenous knowledge. We understand Indigenous knowledge as knowledge based in praxis, rather than as essentialized belief. We locate Indigenous knowledge about the natural world in everyday practices and relations with land, in collective remakings of community, and in the recovery of ancestral wisdom in the face of cultural genocide. Rejecting the hypostatization of science and religion, we suggest that the embedding of “knowledge” (both “western” and “Indigenous,” “modern” and “traditional”) in praxis (always relational, whether acknowledged or not) allows us a rehistoricized, spatially-embedded understanding of scientific knowledge.

Marxist Science Confronts Culture

Current leftist celebrations of Indigenous knowledge rest uneasily atop a history rife with unresolved contradictions regarding the relationship between scientific knowledge and traditional cultural forms. Let us begin by considering a specific historical example.

During the early twentieth century, in Chinese villages, communist revolutionaries prohibited the burning of incense to ward off pestilence, converted temples into schools and administrative offices, and burned religious statuary to cook meat for the villagers. These feats were trumpeted in Mao Zedong’s famous 1927 essay, “Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan.” Mao and other Communist Party leaders prioritized “overthrowing the clan authority of the ancestral temples and clan elders” and the “religious authority of town and village gods,” alongside feudal, landlord, imperialist, and patriarchal powers.5 On this basis, the party built a radical program of science dissemination that lasted through the Mao era (1949-1976). It taught that labor (rather than any deity) created humanity; that women’s exclusion from science was feudal nonsense; and that experience was shaped by social and political forces, rather than a person’s “fate” as interpreted by fortune tellers. 6 This socialist science program was celebrated in Science for the People’s 1974 book, China: Science Walks on Two Legs. 7

Looking back today, do we deem these acts liberating or oppressive? We suggest that the science disseminated would have been more relevant and resilient if it had recognized the cultural entanglements of knowledge rather than stripping facts from context. Were the deposed religious authorities part of a social hierarchy that perpetuated superstition in order to maintain power over the masses? We wish that the revolutionaries had recognized them in their full complexity, as people simultaneously upholding power structures that required transformation while also serving as community elders with access to rich cosmologies and histories.

When the Mao-era state needed knowledge of botanical pesticides, it surveyed rural doctors and monks. This was an acknowledgement that rural and religious people possessed scientific knowledge. But the state’s hostility to religious knowledge led to a highly extractivist approach to traditional knowledge, in which the scientist’s role was to pluck the knowledge from the knower and strip it of its cultural context.8 Similarly, as Gwen D’Arcangelis shows in her contribution to this issue, Mao’s “scientization” of traditional Chinese medicine robbed it of spiritual elements meaningful to many Chinese people, as well as to BIPOC communities in the US.

Leftist movements today rarely pursue anti-superstition campaigns, and instead often defend the legitimacy of traditional knowledge forms, especially those possessed by Indigenous peoples. This shift reflects not just a commitment to anti-colonialism (which Mao and other twentieth-century revolutionaries shared), but the “cultural turn” in scholarship, which since the 1970s has departed from positivism to interrogate the way meaning is constructed, including in the sciences.9 Modern science is now commonly acknowledged as a hegemonic force embedded in and perpetuating colonialism, rather than as an unproblematic tool of liberation. 10

The centering of cultural and epistemic colonialism strikes some on the left as insufficiently materialist. And indeed, it raises problems that we need to address. Indigenous scholar Glen Coulthard has warned of an erosion over the past thirty years of the “radical imaginary within the mainstream Dene recognition and self-determination movement,” owing to the “significant decoupling of Indigenous ‘cultural’ claims from the transformative visions of social, political, and economic change that once constituted them.”11 In Coulthard’s analysis, the celebration and romanticisation of “culture” as something understood separately from land relations and historical relationality has facilitated the Canadian state’s “‘incorporation’ of Indigenous people and territories into the capitalist mode,” which extinguished “what remained of Dene rights and title in exchange for the institutional recognition and protection of certain aspects of Dene ‘culture.’” 12

An emphasis on cultural heritage can also mask questions of class oppression and class-based standpoint epistemology (that is, what people know by virtue of their experience as laborers). We can avoid this pitfall by recognizing the ways in which traditional and Indigenous communities are enmeshed in modern economic systems. For example, Judith Carney has documented the essential importance of West African “knowledge systems” in transporting rice varieties from Africa and cultivating them in American plantations. Carney documents how the preservation and distribution of African crop varieties depended also on provision gardens, or plots of land that enslaved Africans fought to obtain for their own subsistence or even production for market.13 Enslaved Africans on US plantations were simultaneously the inheritors of Indigenous West African knowledge systems and laborers with lived experience navigating specific economic and political relations imposed by slavery. If we are to do justice to their “ways of knowing,” we must center not only cultural identity, but class identity and agricultural practice; not only epistemic colonialism, but also the political economies of capitalism and imperialism. In order to radically rethink our anthropological legacies, in which rural and Indigenous communities are often rendered in terms of a static past, while science and modernization carry elements of a dynamic future, we must forge new habits of braiding together the cultural, the historical, and the political economic dimensions of scientific knowledge.14

Left-Indigenous Resistance Today

Cultural constructions of knowledge and the polyvocality of meaning were necessary correctives to positivism. But the cultural turn, roughly coeval with strategic moves by states and multinational corporations to celebrate Indigenous cultures while expropriating land and resources, left us ill prepared for the neoliberal appropriation of diversity and the acceleration of accumulation by dispossession.15 We are entering a new era of primary accumulation. Land, expropriation, “improvement,” and “development” are occurring again in a grand global cycle, this time using the languages of sustainability, inclusion, and Indigeneity. Fortunately, leftist Indigenous scholars and activists are forging new and effective alliances that simultaneously combat epistemic colonialism and capitalist extractivism.

In India, debates rage over land, religious politics, multinational and domestic capitalist development, and labor. Pro-business Hindutva forces are deploying old strategies of land expropriation while attempting to ideologically capture the identitarian politics of Indigeneity. Non-Indigenous, left critics have cautioned against this appropriation in rhetoric that is suspicious of the language of Indigeneity, while Indigenous scholars are pushing back with an antiextractivist politics rooted in specific ecological zones and deploying non-Hindu cosmologies.16

Politics and theory are closely tied in tribal India. Hidme Markam, an Indigenous (Gond, Adivasi) Indian forest rights activist arrested in 2021, was described by the police as “a dreaded Naxalite who has not just subscribed to the ideology but also participated in several violent attacks.”17 The Naxalites are a Maoist insurgency who were inspired by the Chinese Revolution, but whose current politics are articulated via their specific Adivasi cosmologies and local Indian politics. Markam and other leftist-Indigenous organizers are struggling against right-wing incursions on the Indian Forest Rights Act (FRA), which once legally recognized the rights of forest-dwelling Indigenous communities to manage, use, and live in their traditional forest lands. In these instances, resistance to right-wing extractivist policies and critique of capitalist political economy are survival strategies that undergird the possibility of IK’s very survival.

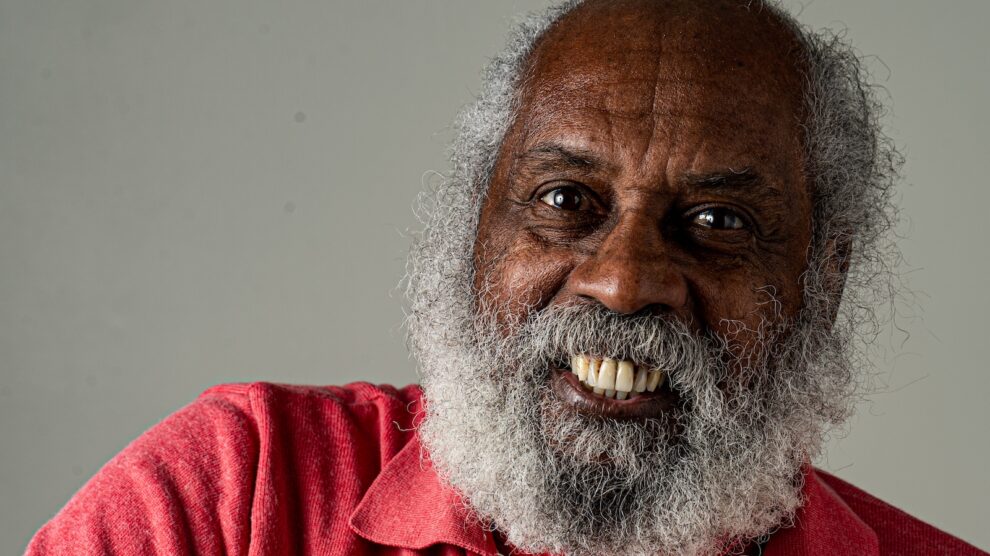

In Brazil, the reemergence of Lula as a leftist leader was built on an Indigenous ecological and social revolution. In this ongoing movement, both leftism and Indigenous narratives are being transformed, each adopting parts of the rhetoric and imagery of the other. For example, Indigenous scholar-activist Ailton Krenak speaks of Brazil’s worst environmental disaster, the spilling of Samarco Corporation’s toxic mining waste into the Rio Doce. This river provides sustenance (for instance, water, fish, and oba seeds) and spiritual meaning to the Krenak people of Minas Gerais.18 Mourning the river’s loss, Krenak refuses to call it dead. In “the Krenak worldview … that toxic mud is not the river. The real river is underground.” The watu (the Krenak name for the Doce river) is like a living spirit in a coma, he explains. Quoting a hydrologist, Krenak underscored the scientific validity of this worldview: “It’s not absurd what the Krenak say, because a body of water, when it suffers damage on the surface, the tendency is for it to dive. It will form groundwater.”19 Krenak’s critique goes beyond the specific corporation and this disaster, as he calls for a rethinking of capitalism and science: “Capitalism throws all this crap at us, which makes it look like if we lose capitalism we’re going to starve. We are calling people to think about another ontology.”20 He describes his Wild Arrow project, “a dialogue between science and the cosmovisions of Native peoples … a dialogue that is being established between different fields of knowledge, an education proposal that goes beyond preparing people for the market, or to be an engineer at NASA, or to push a button at the bank or supermarket.”21

While Ailton Krenak has the reputation of being a “rare” Indigenous theorist and writer, we see his articulation of IK as occurring in tandem with a collective resurgence and rearticulation of Indigenous political power in Brazil. Indigenous theory is not rare, if we are willing to recognize theory-making on the streets, and see praxis as epistemology’s dynamic foundation. For example, a nationwide group of Indigenous women (Articulação Nacional das Mulheres Guerreiras da Ancestralidade, or ANMIGA) describe themselves as ancestral warriors carrying knowledge specific to their diverse biomes: “a large articulation of Indigenous Women from all biomes in Brazil, with knowledge, with traditions, with struggles that add up and converge.”22 While ANMIGA has not yet published work that might be cataloged as IK, they have supported a historic election of Indigenous women to the Brazilian congress, and have built local and global solidarities via protests, Instagram posts, and UN committees. They refer to their theoretical and political practice as “reforesting” the mind and political mentalities. IK is inseparable from this sort of praxis.

History shows us that the forces of capital have not been arrested by left analytics alone, nor solely through cultural claims of Indigenous closeness with nature. In many Indigenous struggles today, we see the power and relevance of materialist analyses of land, labor, and capital—strengthened, often, by cultural claims of specific connections to forms of life that capital threatens to uproot. What might an academic-activist, radical science alliance offer now, at these historic intersections?

The Path Ahead

The contributions in this volume do an impressive job of recounting a variety of Indigenous and other traditional understandings of the natural world that we must learn from. We believe, however, that this is only the beginning of our task, rather than the end point. We wish to revitalize a tradition of historical materialism (HM) and political economic critiques that can help place science, and our critiques of it, on the same plane as our analysis of any other cultural practice. We do not see HM as being philosophically at odds with IK, although historically the two have had difficult relations. We seek an integrated cultural economic and political economic set of critiques, and we find it in everyday and revolutionary struggles globally. With Dr. Lydia Jennings, we hold that IK and science should not be assigned separate platforms.

By recognizing that “ways of knowing” are inseparable from material struggles related to land and labor, and that resistance to epistemic colonialism must be rooted in struggles against primary accumulation, activists and scholars today have arrived at a promising set of conjunctures. Indigenous writers are producing materialist work that grows out of local experience and builds solidarity with global movements. On the left, we have the makings of a resilient, pluralist, and praxis-oriented understanding of all science that can resist a new global politics of rising extractivism and accelerated immiseration. These encouraging alliances are threatened by a rising wave of right-wing reassertion around the world, from the US to India. A new global antifascist movement is necessary, but, this time, science cannot be left to the instrumentalists, the technocrats, and the modernizers. Leftist academics have exciting new analytical resources and practical opportunities to develop robust, liberatory ways to engage with Indigenous and other traditional forms of knowledge. Embarking on our own journey of reevaluation, we might find that advocates of Indigenous and traditional knowledge, in turn, who have been suspicious of deeper engagements with the left, will find newly generative avenues of engagement with radical science.

—

Kavita Philip is the President’s Excellence Chair in Network Cultures at The University of British Columbia, and the author of Civilizing Natures (Rutgers University Press, 2004). She has a Ph.D. in Science and Technology Studies from Cornell, an M.S. in Physics from the University of Iowa, and a B.Sc. in Physics (with Chemistry and Mathematics minors) from Stella Maris College, India.

Sigrid Schmalzer is professor of history at University of Massachusetts Amherst, where she specializes in Chinese history and history of science. She is a founding member of the new Science for the People and the Critical China Scholars, and she is vice president in her faculty union.

Notes

- TEK stands for Traditional Environmental Knowledge; STEM for Science Technology Engineering and Medicine. Photo at https://twitter.com/1NativeSoilNerd/status/1517518440600276993/photo/1. See also “Native Americans Stood up for Indigenous Science,” Buzzfeed News, April 23, 2017, https://www.buzzfeed.com/buzzfeednews/people-are-marching-around-the-world-to-stand-up-for-science?utm_term=.pbV1dOqYwb-.eodowJVAr.

- Megan Bang, Ananda Marin, and Douglas Medin, “If Indigenous Peoples Stand with the Sciences, Will Scientists Stand with Us?” Daedalus 147, no. 2 (Spring 2018): 148–59, https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00498.

- Kavita Philip, “Indigenous Knowledge: Science and Technology Studies,” International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences 7 (2001): 7292–97.

- Richard Levins, Talking about Trees: Science, Ecology, and Agriculture in Cuba (New Delhi: Leftword Books, 2008).

- Mao Zedong, “Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan”, in Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, vol. 1 (Peking: Foreign Language Press, 1967), available on http://marxists.org.

- Sigrid Schmalzer, The People’s Peking Man: Popular Science and Human Identity in Twentieth-Century China (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

- Science for the People, China: Science Walks on Two Legs (New York: Avon, 1974). In 2021, Science for the People published a set of reflective and critical essays on the volume with a link to a digitized version. See https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/rereading-china-2021-special/.

- Sigrid Schmalzer, “Taste 100 Herbs: Material Scarcity and the Significance of Local Plant Knowledge in the Mao-Era Campaign for Native Pesticides,” in Modern Chinese Foodways, eds. Jia-Chen Fu, Michelle T. King, and Jakob A. Klein, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, forthcoming).

- Influential scholars include Michel Foucault, Natalie Zemon Davis (¡Presente!), and Donna Haraway, among many others.

- Lyn Carter, “The Challenges of Science Education and Indigenous Knowledge,” in Indigenous Philosophies and Critical Education: A Reader, ed. George J. Sefa Dei (New York: Peter Lang, 2011).

- Glen Sean Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Red Skin, White Masks : Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 53.

- Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition, 66.

- Judith Carney, Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002).

- Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014); Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2015).

- David Harvey, “The ‘New’ Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession,” Socialist Register 40 (March 2009): 63-87.

- Amita Baviskar, “Adivasi Encounters with Hindu Nationalism in MP” in Economic and Political Weekly 40, no. 48 (Nov. 26-Dec. 2, 2005): 5105–13, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4417462; Alpa Shah, “The Dark Side of Indigeneity?: Indigenous People, Rights and Development in India,” History Compass 5, no. 6 (November 2007): 1806–32, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-0542.2007.00471.x; Dolly Kikon, Living with Oil and Coal: Resource Politics and Militarization in Northeast India (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2019); Charlotte Eubanks and Pasang Yangjee Sherpa, “We Are (Are We?) All Indigenous Here, and Other Claims about Space, Place, and Belonging in Asia,” Verge: Studies in Global Asias 4, no. 2 (Fall 2018): vi–xiv, https://doi.org/10.5749/vergstudglobasia.4.2.00vi.

- Sukanya Shantha, “Activist Hidme Markam Walks Out of Jail As Police Fail to Prove Alleged Terror Cases,” The Wire, Jan. 5, 2023, https://thewire.in/rights/hidme-markam-activist-acquit-jail.

- Cleiton Campos, “The future is ancestral: Interview with Ailton Krenak,” in Where the Leaves Fall, Issue #8, https://wheretheleavesfall.com/explore/article-index/the-future-is-ancestral/; Anna Souter, “Wild Arrows,” in Where the Leaves Fall, Issue #11, https://wheretheleavesfall.com/explore/article-index/wild-arrows/; Luisa Torre and Patrik Camporez, “Life for Brazil’s Krenak after Fundao dam collapse,” last modified July 3, 2017, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/7/3/life-for-brazils-krenak-after-fundao-dam-collapse.

- Campos, “The future is ancestral: Interview with Ailton Krenak.”

- Krenak’s critique goes beyond the specific corporation and this disaster, as he calls for a rethinking of capitalism and science: “Capitalism throws all this crap at us, which makes it look like if we lose capitalism we’re going to starve. We are calling people to think about another ontology.”

- He describes his Wild Arrow project, “a dialogue between science and the cosmovisions of Native peoples … a dialogue that is being established between different fields of knowledge, an education proposal that goes beyond preparing people for the market, or to be an engineer at NASA, or to push a button at the bank or supermarket.”

- ANIMGA website, https://anmiga.org/.