Breaking the Binary in Ecology and Beyond:

What Indigenous Ecologies Can Teach Us About Resisting Xenophobia

By Maya Cohen and Michelle Zhang

Volume 26, no. 2, Ways of Knowing

Recently, a friend from New York City visited us and recounted that there were spotted lanternflies smushed all over the sidewalk. She explained that people go out of their way to step on them because they know they are invasive. When she asked another New Yorker where the hated fly came from, he responded, “Oh, probably Japan.”

Immediately, we recalled other related incidents. One of our colleagues on a farm made a racist comment related to Asian lady beetles earlier in the year. In searching for information about spotted knapweed a few months prior, we stumbled across an online forum member speculating about whether the plants came from the tundras of Russia, given their stubborn and aggressive nature. During conversations in urban gardens, farming workshops, and casual chitchat about the land, we noticed that people often assumed dominating plants had Oriental origins.

Who could blame them? Thinking about famous US invasive species off the top of our heads, we realized that many of the names were associated with Asia. To list a few: Japanese beetle, Asian lady beetle, kudzu, Burmese python, Asian carp, etc. Asking ChatGPT, “Where do most invasive species in the US originate?” returned this answer, “Asia: Many of the most problematic invasive species in the United States have their origins in Asia.” Popular media depictions of invasive species often associate such species with East Asia, like a Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) documentary that “tracked many [invasives] back to China,” or a New York Department of Environmental Conservation documentary whose definition of invasive species included that “around here it’s typically from Asia, from China.”1 Species that have a large global native range are still unfairly called Asian or Japanese, such as “Japanese blood grass,” which is also native to many areas across the Americas, Eurasia and Africa, or “Japanese stiltgrass,” whose native range includes regions across Eurasia, including Turkey and the Caucasus Mountains. Of course, some invasive species associated with non-Asian origins also get press attention–English ivy, European starling, and Norway maple make several “top invasive” lists. But popular discourse around these species lacks the racialized paranoia haunting Asian invasive species, and their existence doesn’t negate the popular perception that invasive species in the United States most commonly come from Asia, Japan in particular.

By drumming up the threat of an uncontrollable outside invader, be it foreign humans or foreign plants, colonizers associate themselves with nativeness and draw attention away from the fact that they dominate a place which they also do not originate from.

As Asian Americans working in Indigenous-led land projects, we have long been interested in the frequently xenophobic undertones of conversations around invasive species. We speculated whether an overemphasis on Asian origins of invasive species pointed to a cultural bias in US popular ecology, or if we were projecting our own experiences onto our non-human counterparts. Indeed, invasion ecology provides a compelling metaphor to explore personal confusions about our place in an assumed white-Indigenous binary, or in other words, the popular discourse around colonialism that implies all relevant actors are either white or Indigenous. But is invasion ecology just a metaphor? By synthesizing the anti-colonial and anti-xenophobic critiques of invasion ecology, can we develop a more comprehensive, interrelated understanding of both?

Ultimately, we find that the false binary of native versus alien outsider is used by colonialism, and the colonial ways of knowing underlying invasion ecology, to legitimize itself. By drumming up the threat of an uncontrollable outside invader, be it foreign humans or foreign plants, colonizers associate themselves with nativeness and draw attention away from the fact that they dominate a place which they also do not originate from. Migration and belonging are complex, and erasing such complexities is a central part of how colonial hierarchies are maintained. On the flip side, the key to dismantling such hierarchies is examining these erased complexities, whether it be through honoring the heterogeneity of Indigenous knowledge systems or grounding ourselves in observation rather than assumptions about the non-human relatives in our ecosystems.

To explain the xenophobic associations of invasive species, we turned to Iyko Day’s book Alien Capital.2 Day describes how, in the role of the “alien,” Asians are racialized to represent “alien capital”–a hyperproductive, dangerous, and uncontrollable force. This racialization has historically been applied to Asian working-class labor as a competitor to white laborers, and today takes the forms of the model minority stereotype and fear of Chinese investment and economic development. In both cases, Asian people and their foreign capital are made to represent the greedy, monopolistic, and malevolent face of capitalism as a tool to paint white settler capital as a safe and liberalizing counterforce.

The alien capital concept immediately recalls rhetoric towards invasive species, which are feared for their extreme and uncontrollable productivity that pose a danger to commodifiable ecosystems. Day goes on to explain the reinforcing relationship between colonialism and anti-Asian xenophobia in North America, arguing that the Asian “alien” has often been used as a comparison to reinforce the indigeneity of white settlers by stoking fear over a new foreign enemy. While white indigeneity may seem like an oxymoron in this context, Day argues that “settler identity is heavily invested in appropriating indigeneity.”3 The “indigenizing” of white people justifies why white settlers have a right to, naturally belong in, and are beneficial to the lands they colonize.

The same colonial logic is fundamental to invasion ecology. The Science for the People article “Asking the Cattails Why They Are Here” by Promita Ghosh and Amitava Banerjee debunks the “scientific” basis for invasion ecology and explains the colonial origins of the theory in the 1958 publication of The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants by British ecologist Charles Elton.4 Elton was a prominent ecologist towards the end of the British Empire, a time when the field of ecology flourished as a tool to maximize resource extraction and control colonized peoples. Following from this origin, determinations of “invasiveness” are generally based on a species’ value for capitalist markets and its “potential threat to the sustainability of existing colonial economies.”

Elton was extremely politically influential, shaping British national policy on conservation.5 For example, Elton’s research on the population dynamics of lemmings was used to predict mild arctic summers for the British Petroleum Company’s oil prospecting. His work was used to optimize the British control of Indigenous fur-trade workers in so-called Canada.6 Elton was also a key advocate for managed nature conservation areas, which now comprise 15% of Earth’s land surface and are often used as an excuse to remove Indigenous people from their territories while permitting extractive industries.7

Like nature conservation areas, invasion ecology is based on the idea of a “natural” ecology. Many definitions of invasive species make reference to where a species does or does not “naturally” occur, drawing on the colonial construct of a “natural” order that is untouched by civilization.8 This construct facilitates the use of the terra nullius argument to steal Indigenous land by allowing colonizers to imagine that the land we now call the “United States” was naturally abundant and underused by Native peoples. In reality, “natural” abundance was a direct result of Indigenous land stewardship and knowledge.

However, this anti-colonial analysis alone doesn’t explain how colonial science has justified the glaring contradiction of championing native species while dismissing native peoples and their cultures as inferior. According to invasion ecology, native species are threatened by invaders because they don’t occupy all the ecological niches–therefore we must protect them. But when settlers justify the violent displacement of Indigenous peoples by pointing to all the empty “niches” they supposedly left, invasion is seen as natural, inevitable, and God’s will. Day’s theory of alien capital provides an answer with her explanation of how settler identity appropriates indigeneity by using foreigners as a foil. Following this logic, the colonial narrative associates native (naturally occurring) species with the “naturally occuring” white settlers, as opposed to invasive species which are associated with threatening and “unnatural” foreigners.

Invasion ecology’s founding father used his own xenophobic fears of the “unnatural” to justify the study of invasion ecology. Elton opens his book by giving examples of “two rather different kinds of outbreaks in populations: those that occur because a foreign species successfully invades another country, and those that happen in native or long established populations.”9 Despite recognizing that the same ecological pattern can occur regardless of foreign/native status, Elton decides that his book ought to be “chiefly about the first kind – the invaders,” because of his fear of migration. Or, as he puts it, because he is “living in a period of the world’s history when the mingling of thousands of kinds of organisms from different parts of the world is setting up terrific dislocations in […] the natural population balance of the world.”10

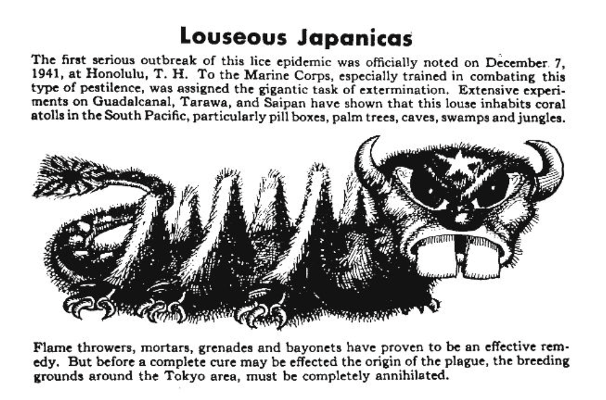

Though Elton canonized invasion ecology in the scientific mainstream, its underlying sentiments existed decades before his 1958 publication. In her book Biotic Borders, Jeannie Shinozuka tracks the intertwined North American histories of anti-Japanese xenophobia and the fears of invasive Japanese species, beginning from the 1890s.11 Shinozuka’s work highlights how invasion ecology’s xenophobic origins have led to xenophobic applications of the theory. From Japanese lice being associated with a racialized military threat during WW2, to an article that describes Japanese beetles (called “Jap Bugs” in some historical sources) as having “a truly Japanese characteristic in its rate of increase,” Biotic Borders cites a plethora of instances where anti-Asian xenophobia drove the fear of invasive species and vice versa.

The common theme between all of these intentionally dispersed plants is that colonial land management has lost control over their populations.

These sentiments led to closely associated plant and human immigration restrictions. For example, one of the earliest invasive species controls, “Plant Quarantine Number 37” (PQN37), was passed just a year after the Asiatic Barred Zone immigration ban. PQN37 was described by the contemporary president of the American Forestry Association as closing the “open door to plant immigrants,” hoping that “the treasonable activities of these enemy aliens will be curbed.”12

While the historical evidence presented by Shinozuka and other researchers makes it clear that the label of “invasive” is certainly linked to a negative value for capitalist profits, many invasive species do have a commodifiable use–a fact that is not lost on the very institutions that push invasive species control. Despite narratives of invasive species secretly hitching a ride across borders, many invasive species are intentionally imported and dispersed by industry or government for economic reasons. Kudzu was spread by the military to decrease erosion during the dust bowl, Asian lady beetles were spread by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to control aphids, and ornamental plants like Japanese honeysuckle were imported to fulfill an Orientalist desire for exotic garden plants.13

The common theme between all of these intentionally dispersed plants is that colonial land management has lost control over their populations. Similarly, as pointed out in Alien Capital, the industriousness of Asian workers is either as reviled as “yellow peril” or fetishized as the model minority myth depending on how well the settler colonial order is “in control” of these workers. The fears of both invasive species and Asian capital don’t stem from their lack of productivity, but from a perceived uncontrollable productivity that does not benefit the settler colonial order.

Though environmental historian Peter Coates’ book on the topic concludes that there is no longer a correlation between fear of alien species and alien humans like there was in the past, East Asian species continue to receive racialized hate, and the reasons for this need to be more seriously addressed.14 Whether it is Barack Obama appointing an “Asian Carp Czar” to eliminate the fish that National Public Radio (NPR) calls an “alien” who “eats like a sumo wrestler” and “makes Saddam Hussein seem cuddly,” or it is Vice News proclaiming that the lanternfly–“a bizarre Asian pest”–“is actually an eco-terrorist,” the perception of an invader coming from Asia is still alive and well in American society.15

Even if, for the moment, this association is reserved for non-humans, the potential for it to slip into xenophobia is always lurking. This is evidenced by the rapid outbreak of anti-Asian hate during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many Americans–most notably then-president Donald Trump–fixated on the virus’s Chinese origins as a strawman concern, but simultaneously refused to protect themselves or others against it.16

While invasion ecology is problematic and simply unhelpful in many contexts, we recognize that the phenomenon it attempts to address is not entirely fabricated. There are ecosystems where certain species are clearly dominating, and, as Elton argues, this undesired domination is more frequent in weakened ecosystems. However it is questionable whether “native” or “invasive” origin labels are useful to explain this occurrence of domination. While there is continued, though declining, scientific evidence to support some of the hypotheses proposed by invasion ecology, these hypotheses do not compare the likelihood of a native versus an introduced species dominating a landscape, or becoming a pest.17Elton’s own book begins by stating that both native and introduced species can take over.18

One of the first examples Elton gives of an “invasive species” in the UK is the Colorado potato beetle, which we can say from personal experience is equally able to devastate a crop in its native North American range as it is in Europe. In our experience farming potatoes, it was not the beetle itself that inherently caused the devastation, but the weakness in the landscape created by surrounding industrial potato monoculture. Similarly, there is a growing fear that invasive species are spreading to ecosystems weakened by the climate crisis, compounding the effects of climate change on ecosystem degradation and the extinction crisis.19

Yet the designation of species as “naturally occuring” (or not) becomes even more dubious in a place where the landscape has been drastically altered through industrial agriculture or climate change. Why would we expect the same set of species that originated in a location to continue thriving there in such different conditions? On the land we steward, which has been deforested for agriculture and grazing, the “invasive” knapweeds were able to create life in places where no “native” species had returned, growing taproots that broke up land hardened from drought and providing living ground cover that restores the soil.

Placing the blame on invasive species for the extinction crisis and ecological degradation perfectly follows Day’s theory: the fear of alien invaders is used to divert blame from the colonial extractive industries and capitalist system that are responsible for climate change and habitat loss.

Even as the climate crisis reveals obvious contradictions in colonial land management, the desire to return to a precolonial “nature” remains strong. While the Hawaiian government spends millions of dollars to destroy “invasive” mangrove forests, other countries spend as much as $500,000 per hectare to restore mangroves in their native habitat.20 In the last decade, the world spent an estimated $4.2 billion per year managing invasive species.21Especially as climate change speeds up the forced migration of all species, it is clear that transitioning to an alternative framework for relating to introduced species is urgently needed.

The ecology embodied by many Indigenous cultures allows us to understand plants and animals based on our relationships with them–that is, the extent to which they provide for us, harm us, and in what ways they do so–as opposed to through their origins.

We propose looking to Indigenous ecological knowledge and leadership as the solution. Ghosh and Banerjee’s article similarly calls for the centering of Indigenous worldviews, highlighting literature on the relational and kin-centric ecology of Anishinaabe and Raramuri cultures. Professors Nicholas Reo and Laura Ogden’s ethnographic research showed that “Anishinaabe knowledge values observations,” which helps Anishinaabe people understand why new species have arrived and “to investigate the nature of novel relationships” between themselves and the newcomers.22 Raramuri professor Enrique Salmón’s work explains the kin-centric worldview in which “Indigenous people view both themselves and nature as part of an extended ecological family that shares ancestry.”23 Relational and kin-centric ecology are seen as a “core feature” of many other Indigenous worldviews as well.24 For example, in the Hawaiian language, residents are colloquially called kama’āina, literally meaning child of the land, and the word for family, ohana, translates to taro stalk.25 In Māori culture, the Whakapapa, or genealogy stories, “express our need for kinship in the world” and “describe the relationships between humans and the rest of nature,” explains Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal.26

The ecology embodied by many Indigenous cultures allows us to understand plants and animals based on our relationships with them–that is, the extent to which they provide for us, harm us, and in what ways they do so–as opposed to through their origins. This can be seen in Hawaii, where communities have developed a positive relationship with the kiawe or mesquite tree in the face of a changing landscape. Introduced in 1828 from France and deemed by contemporary conservation plans as invasive, the kiawe is being used as firewood in the face of declining native tree populations, which had historically been the providers of firewood.27

It is worth noting here that Māori and Hawaiian peoples, as Polynesians, come from voyaging traditions “who have intentionally migrated plant and animal populations deemed useful into new or existing homelands over many thousands of miles and years.”28 Their ability to thrive and build cultures deeply connected to once unfamiliar land depended on using both introduced and native species, rather than fixating on one as good and the other as bad. They observed relationships and passed down “the ongoing growth of ‘best practice’ as a result of socio-ecological consequences” to next generations in the form of voyaging stories.29

Does relational, kin-centric ecology mean that all introduced species are positively regarded though? Not always. In Aotearoa (known as New Zealand in English), Māori people raised concerns over the nanakia, or introduced pests, that arrived with the European colonizers in the 19th century. Rats were, and sometimes still are, seen as one such nanakia, but today they are “understood and therefore managed differently based on [their] behaviour and history in different regions [of the country] and circumstances.”30 Hence, the concept of nanakia differs from “invasive species” because it is defined by the nature of people’s relationships to the species as opposed to solely its origin. Furthermore, the Māori language includes three additional terms with varying meanings and connotations for non-human newcomers, reflecting a more nuanced understanding of them that contrasts the binary logic of invasion ecology and colonialism at large.

On the other end of the spectrum, in Anishinaabemowin, there is not even a loose potential translation for “invasive species,” as “the term itself is considered disrespectful.” This reflects the Anishinaabe worldview that all beings “were given original instructions by the Creator,” and when they disrupt an ecosystem “outside their original communities,” an appropriate response can even include “seeking traditional and cultural knowledge from areas where beings may be native, and the creation of new reciprocal relationships through ceremony and harvest.”31

As evidenced by the linguistic diversity across several Indigenous ecologies, we cannot simply adopt Indigenous ecology as a monolithic alternative. Furthermore, the historic power dynamics between science as an institution and Indigenous communities creates a risk of appropriation. Each Indigenous culture’s knowledge system reflects unique histories and relationships with the different lands they call home. Sometimes, land stewards are fortunate to have the guidance of people who carry the Indigenous knowledge specific to the land. In this case, they should be given autonomy in decision-making and their voices centered. But other times, land stewards lack such guidance, even when we seek it out. In those situations, we can at least be good future ancestors who observe, learn, and shape the cultures we create around such humility.

We work to keep these dominating species in check. At the same time, we recognize that they are not categorically bad.

On the land we ourselves steward for an Indigenous-led rematriation project in Northern New Mexico, Bueno Para Todos, we are in community with Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals who have ancestral knowledge of the ecosystem, but also many Indigenous folks local to the area who have lost much of the memory and practice of their cultures due to violent colonization. Furthermore, those with Indigenous knowledge cannot always be on the land to guide us, for reasons that appear logistical but ultimately connect to historic, structural oppression of Indigenous peoples and their ways of knowing. Hence, we often ground ourselves in observation of the land and an intention to build relationships with the other beings living here, the same way we would with a human neighbor. We have observed that some non-native species, such as spotted knapweed, have a tendency to take over an area, making it difficult to grow or forage a diversity of plants there. We have also observed cultivated plants (e.g., alfalfa) and native plants (e.g., coyote willow) do the same. We work to keep these dominating species in check. At the same time, we recognize that they are not categorically bad. The late director of the project, Yvonne Sandoval, returned to these lands to reconnect with her Indigenous roots, and she did so with curiosity and respect for all the beings now living here. She encouraged us to understand the gifts of these species, such as medicine; food; and resilient ground cover, which is an integral part of soil health in an arid landscape.

As the field of ecology engages in critical self-reflection, it becomes increasingly more open to Indigenous ways of knowing than before, but openness is just the beginning. How do we make the transition to an alternative paradigm of relating to species beyond their origin? In order to uplift Indigenous leadership and practice kin-centric seeing, we must also unlearn colonialism lest we unintentionally replicate the framework we are trying to replace. Prominent Indigenous scholars, such as Yásnaya Elena Aguilar Gil, argue that indigeneity means nothing without colonialism. Aguilar argues that “Indigenous” is a political category created and defined by colonial powers in order to oppress and lump together every culture that wasn’t created by colonial powers.32

From this understanding of the label “Indigenous,” it becomes apparent that dismantling colonial ecology and uplifting Indigenous ecologies are one and the same. Unpacking the ways in which colonialism has shaped our relationships is the first step towards adopting relational ecology. This includes our relationships with newcomers, and understanding xenophobia as a tool to uphold colonial power. The fight for decolonization therefore must include a fight against xenophobia, and the fight against xenophobia must be part of a broader struggle to decolonize.

Invasion ecology proves to be not a metaphor, but rather a mirror, for how we are taught to relate to one another under colonial culture; as belonging or invading, good or bad. There is always a binary. The gray space in between is dismissed, and anything off the spectrum or representing both ends is not even acknowledged. We must continue to examine such patterns of colonial logic as we struggle to decolonize ecology and beyond; we cannot let decolonization be co-opted into just another meaningless buzzword or trend for further oppression to hide behind. Decolonizing science does not mean distinguishing native species as good and all else bad, as invasion ecology implies. Instead we must examine how colonialism has informed our understanding of non-human kin, and learn from the many Indigenous ways of knowing as an antidote. Similarly, for humans, decolonization does not mean all native people are categorically good and everyone else is bad. Hyperfixation on superficial binaries will not allow us to better understand the world, nor will it liberate us. Instead we must observe how each of us internalizes the logic of colonialism, and begin healing the harm it has caused our relationships with ourselves, each other, and this Earth.

Meet the contributors:

Michelle Zhang and Maya Cohen: Michelle and Maya are land stewards based at the Bueno Para Todos Farm healing justice hub in rural New Mexico, and are organizers connecting local and international liberation movements. IG: @buenoparatodosfarm

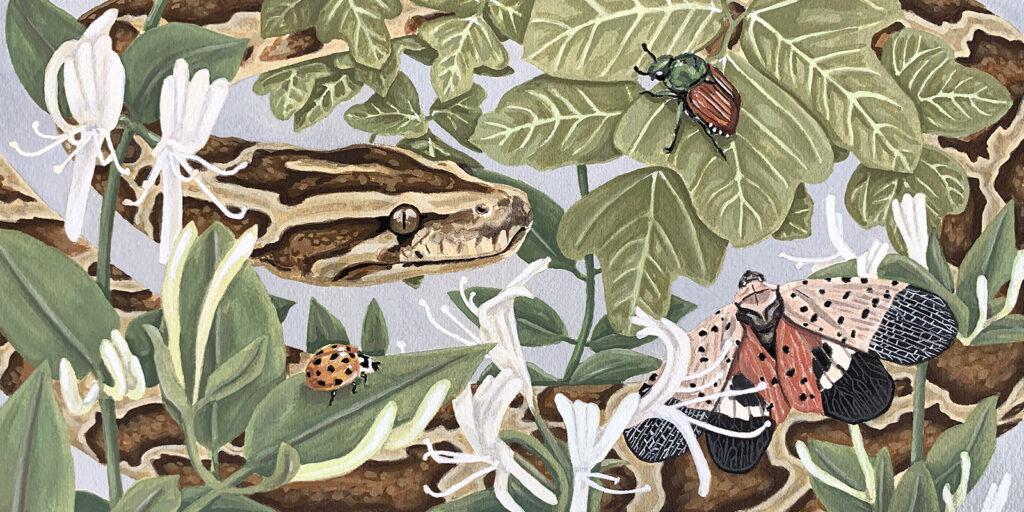

Jenna Kurecki (BFA): I’m a traditional artist specializing in nature illustration. I create to understand the world, to process existence, and appreciate its beauty. In turn, I create to communicate information, to prompt active seeing rather than passive looking. www.jennakurecki.com. IG: @jennakureckiart

Notes

- Uninvited: The Spread of Invasive Species, PBS, April 21, 2022

- Iyko Day, Alien Capital, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

- Iyko Day, Alien Capital, 19

- Promita Ghosh and Amitava Banerjee, “Asking the cattails why they are here,” Science for the People 24, no.3 (2021)

- Daniel Simberloff, “Charles Elton: Pioneer Conservation Biologist,” Environment and History 18, no. 2, (May 2012): 183-202

- Peder Anker, Imperial Ecology: Environmental Order in the British Empire, 1895-1945.

- Alexander Zaitchik, “How Conservation Became Colonialism,” Foreign Policy, July 16, 2018

- For example, see the Fish and Wildlife Service definition: “Invasive species are non-native plants, animals and other living organisms that thrive in areas where they don’t naturally live and cause (or are likely to cause) economic or environmental harm, or harm to human, animal or plant health. Invasive species degrade, change or displace native habitats, compete with native wildlife, and are major threats to biodiversity.” United States Fish and Wild Service, “Invasive Species,” accessed December 21, 2023

- Charles Elton, The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants, (London: Chapman and Hall, 1972), 13

- Elton, ibid.

- Jeannie Shinozuka, Biotic Borders (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2022).

- Shinozuka, Biotic Borders, 96-97

- For example, see this video on invasive species from a United Nations Environment Programme project: “Invasive Species: Hitching a Ride,” GRID-Arendal, accessed December 21, 2023; “Multicolored Asian Lady Beetle,” Penn State Extension, June 19, 2023; Bill Finch, “The True Story of Kudzu, the Vine That Never Truly Ate the South,” Smithsonian Magazine, September, 2015; Orientalism is a narrative that creates the imagined concept of the “Orient,” which is defined only by its difference from the “West”. The “Orient” is stereotyped as barbaric, exotic, passive, feminine, etc. as a tool for the “West” to dominate and control it. See Edward Said, Orientalism, (1978, Pantheon Books).

- Peter Coates, American Perceptions of Immigrant and Invasive Species (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2007).

- David Gura, “White House ‘Asian Carp Czar’ Outlines His Strategy For Eradicating Species,” NPR, (Oct 7, 2010); Andrew Zaleski, “America Isn’t Ready for the Lanternfly Invasion,” Bloomberg, (October 2, 2018); VICE News, “Meet the Vigilantes Trying to Wipe Out the Spotted Lanternfly,” YouTube, (Oct 28, 2021)

- Mishal Reja, “Trump’s ‘Chinese Virus’ tweet helped lead to rise in racist anti-Asian Twitter content: Study,” abcNews, (March 18, 2021)

- Jonathan Jeschke, et al., “Support for Major Hypotheses in Invasion Biology Is Uneven and Declining,” NeoBiota 14 (2012)

- Charles Elton, The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants, (London: Chapman and Hall, 1972), 13

- IPPC Secretariat, Scientific review of the impact of climate change on plant pests – A global challenge to prevent and mitigate plant pest risks in agriculture, forestry and ecosystems, (Rome, IL: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2021)

- “In Hawai`i, Mangrove’s Drawbacks Outweigh Benefits,” Environment Hawaii, (June 30, 2011); Roy Lewis, “Mangrove Restoration – Costs and Benefits of Successful Ecological Restoration,” In review, Proceedings of the Mangrove Valuation Workshop, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, (48 April, 2001).

- Ross Cuthbert, et al., Biological invasion costs reveal insufficient proactive management worldwide,” Science of the Total Environment 819 (2022)

- Nicholas J. Reo and Laura A. Ogden, “Anishnaabe Aki: an Indigenous Perspective on the Global Threat of Invasive Species,” Sustainability Science 13, no. 5 (2018): 1443–52.

- Enrique Salmón, “Kincentric Ecology: Indigenous Perceptions of the Human–Nature Relationship,” Ecological Applications 10, no. 5 (2000): 1327–32.

- Annie Milgin, “Sustainability crises are crises of relationship: Learning from Nyikina ecology and ethics,” People and Nature 2, no. 4 (2020)

- Kekuhi Kealiikanakaoleohaililani and Chirstian Giardina, “Embracing the sacred: an indigenous framework for tomorrow’s sustainability science,” Sustainability Science 11, no. 1 (2015)

- Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal, “Te Ao Mārama – the natural world,” Te Ara, accessed October 16, 2023, quoted in Kekuhi Kealiikanakaoleohaililani and Chirstian Giardina, “Embracing the sacred: an indigenous framework for tomorrow’s sustainability science.”

- Priscilla Wehi, et al., “Contribution of Indigenous Peoples’ understandings and relational frameworks to invasive alien species management,” People and Nature 5, no. 5 (2023): 1403-1414.

- Wehi, et al., 1405.

- Wehi, et al., 1405.

- Wehi et al., 1405

- Wehi et al., 1408.

- Yásnaya Elena Aguilar Gil, “We Were Not Always Indigenous,” Adi Magazine, 2022