Beyond Development and Extractivism

New Paradigms for Health

By Erika Arteaga, Todd Jailer, Baijayanta Mukhopadhyay, and Amulya Nidhi—People’s Health Movement Ecosystem and Health Working Group

Volume 25, no. 2, Bleeding Earth

Economic growth has become the dominant paradigm of social organization. This paradigm subordinates our well-being to the growth of production and consumption, of which the model regards as “progress,” while inequities and lack of access to life’s necessities are reduced to economic factors, i.e., Gross Domestic Product and the Human Development Index.1 In such a framework, human health is reduced to just another commodity. In response, on the basic premise that health is more than a biological condition, the People’s Health Movement (PHM) has focused on the transformation of the social determinants of health. Our Ecosystem and Health Working Group draws inspiration from the insights and alternatives represented by the Andean Indigenous paradigm of Sumak Kawsay (Buen Vivir), among other models, that subvert growth-centric models while promoting health as a public good and a civil right.2

In critiquing the development paradigm and exploring alternatives, extractive industries are a critical area of our work. The development paradigm operates through the system of extractivism, a mode of accumulation that favors the extraction of natural resources—gold, bauxite, cobalt, copper, diamonds, lithium, manganese, tin, uranium, zinc, fossil fuels, agribusiness, forests, fish, and now narcotics—from the Global South.3 The extractivist project began with the conquest and colonization of America, Africa, and Asia.4

Both right- and left-wing governments across the world, especially in Latin America, are captured by belief—along with their allies in the emerging geopolitical centers of China, India, and Russia—in this development paradigm. Communities continue to experience displacement, heightened militarization, violence and repression, increased incidence of communicable diseases and health problems resulting from exposure to toxins, and the loss of social services, land, water, and livelihood.5 All of these are linked to an extractivist project driven by global financial capital that promotes an unsustainable and inequitable development model that threatens the people’s and planet’s health.6 The right to health is not compatible with the financing of national health systems through revenues derived from intrinsically life-destroying activities, such as oil and mineral extraction.

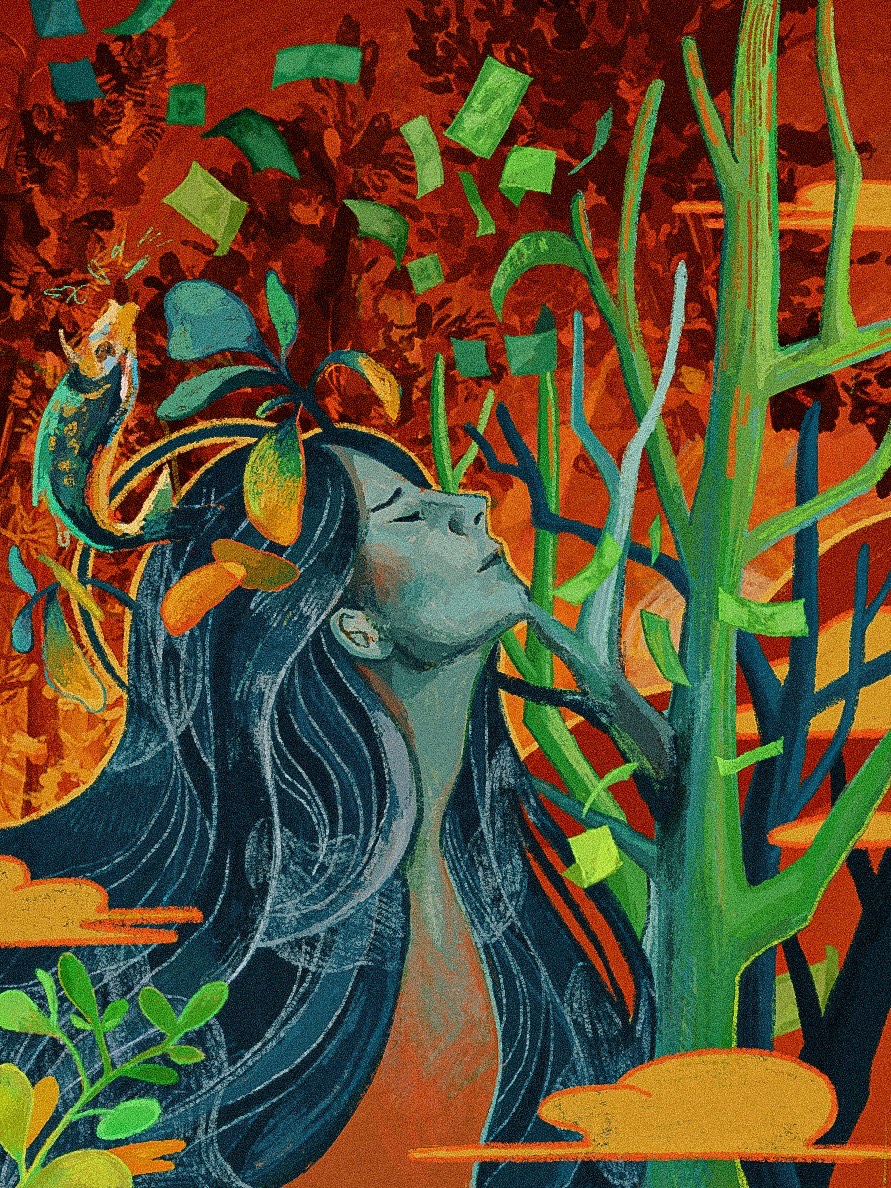

Sumak Kawsay, or Buen Vivir, considers nature as a living being, a subject of care and rights.

In a global economy predicated on the extraction of resources and the relentless pursuit of profit, systems of oppression (capitalism, white supremacy, patriarchy, ableism, etc.) simultaneously drive the interrelated processes of health inequalities and climate change. Exacerbated by free trade agreements that protect capital mobility as instruments of colonial domination, the capitalist development paradigm privatizes health services in impoverished and racialized sectors of the Global South. Meanwhile, fragmented health programs for the poor population—referred to locally as salud de pobres para pobres (“poor health services for the poor”)—are given as a “reward” for assimilation into a consumption economy while homes and territories are destroyed as environmental sacrifice areas.7

Reorienting extractivist development models toward a holistic conception of health is critical for achieving an energy transition that is equitable and does not exacerbate the detrimental health impacts of our current energy system. As we pursue strategies like a Green New Deal (more on this later), integrating these concepts are crucial. In the face of the existential threat of climate change, discussions of green energy or carbon markets that do not question the fundamental growth-centric, capitalist approach will hardly mitigate its damage, and certainly will do nothing to repair it. Indeed, replacing fossil fuels with energy sources dependent on the mining industry will continue to negatively affect the Global South, while the liberal discourse of “progress,” to raise people’s standards of living, remains a dead end of westernized modes of production and living.8

Alternatives to Development: Sumak Kawsay or Buen Vivir (Good Living)

Sumak Kawsay, or Buen Vivir, is an Indigenous philosophy of Ecuador that provides a useful paradigm to challenge extractivism’s impact on people’s health. This philosophy first considers nature as a living being, a subject of care and rights. Human beings and their health are not separate from nature; instead, our survival and integrated well-being are contingent on larger ecosystems. Health in Kichwa/Indigenous and Capitalist/Western worldviews are perceived differently, which results in not only differing human health outcomes, but also different essential premises of history and human’s place in nature from distinctive starting positions (Table 1).9

Table 1: Distinct features of the Sumak Kawsay or Buen Vivir worldview as explained by Luis Maldonado Ruiz.

| Capitalism | Sumak Kawsay |

| ● Property is privately held, and capital privately accumulated

● Individual subject (mainly economic rights – Homo economicus) ● Seeks individual economic benefit ● Accumulation ● Market freedom ● Obsession for economic growth ● Private business predominance ● Natural “resources” degradation ● Production toward satisfying needs (wants) created by companies (new illnesses) ● Based on market rules: supply and demand |

● Property is held collectively or in common, familiar property (ancient commons)

● Collective subject (collective rights) ● Seeks community well-being ● Institutions of social reciprocity/ redistribution (nature) ● Market: space of exchange of surplus and to supplement needs (trueque) ● Human being as a part of nature (sacred reciprocity) ● Based on needs satisfaction and establishment of alliances to guarantee that all community members have equitable access to resources |

Health in a capitalist society is a product of individual action, submission to the medical-industrial complex, subsumption of people to the agribusiness-dominated food system, and the pathologization of physiological processes of birth and aging. Sumak Kawsay is tied to human beings and their relationships to their communities and lands; life processes are considered sacred and connected, wherein food sovereignty is an expression of collective health.10 The Sumak Kawsay worldview is not particular to Andean communities (Ecuador and Bolivia); Aotearoa (New Zealand) has also passed the Te Awa Tupua Act, which recognizes jurisdictional rights for the spirit that protects water as reparation for the Indigenous Māori.11 While other Indigenous and struggling peoples hold a variety of worldviews, most share the understanding that development to meet human needs has been replaced by development to accumulate wealth for international capital to the detriment of the health and well-being of people and the planet.

The principles of Sumak Kawsay or Buen Vivir offer a civilizational alternative. These principles are important in our struggles for health and against the colonial extractivist development model that pillages the land, fueling climate change and exacerbating pre-existing social inequities. In Global Health Watch 6, we have brought together several case studies that make clear what extractivist capitalism entails:

- negates Indigenous rights to pursue traditional livelihoods, even in the social democracies elevated as examples of equitable capitalist societies, such as with the Saami people in Sweden;

- burdens women with the impacts of planetary destruction, as with the case of climate change fueled wildfires in Australia;

- imprisons and murders environmental defenders in numbers that increase yearly in the Philippines, Colombia, Central America and elsewhere;

- ruins the lungs and lives of hundreds of thousands of mine and quarry workers in India

- turns areas of the United States inhabited primarily by people of color and poor people into unlivable “sacrifice” zones, as with the Gulf Coast’s “Cancer Alley.”12

Along with these stories of environmental and human destruction, PHM coordinates locally and internationally with organizers and activists in building movements and hope. The struggle against extractivism in Ecuador provides one example.

PHM Ecuador and the Need for Solidarity in Our Struggles

Hosting the Second Assembly in Cuenca in 2005, PHM recognized that “natural resources” must be considered public goods, and that the centrality of the Right to Water and the implementation of the precautionary principle were fundamental to the Right to Health. We already heard “The Voices of the Earth are Calling” for an urgent moratorium on extractive activities.13

PHM-Ecuador has long defended the rights of nature as recognized in the 2008 Constitution of Ecuador and the Sumak Kawsay proposal. We worked in solidarity with the YasunidXs activist collective dedicated to protecting the Yasuni ITT National Park from oil extraction.14 The failure to protect that territory by Rafael Correa’s government (2007–2017) pushed the struggle to defend nature into new arenas. While the global left applauded Correa’s government for its inclination to redistribute income created by extractivism, his government opposed land protection movements nationally—particularly the Indigenous movement—sometimes violently.

In 2019, PHM-Ecuador organized international solidarity from PHM-Canada to draft an Amicus Curiae (a “Friend of the Court” expert intervention) asking the Ecuadoran government to give the city of Cuenca the right of consultation on whether they wanted mining activities near their water sources. The impact of the Canadian intervention was strengthened by the fact that it was Canadian mining companies that were threatening the health and the right to water of Ecuador’s third largest city. Although this appeal to the Constitutional Court failed, the added support in Ecuador and international solidarity strategically pressured a second attempt in 2021 that resulted in a popular consultation wherein 80 percent of Cuenca’s population voted to prohibit mining in the water recharge zones of the Tomebamba, Tarqui, Yanuncay, Machángara, and Norcay rivers. This was a stunning and hard-fought gain.

Building on that first experience, we have strengthened ties between Ecuadoran and Canadian social movements (Mining Watch, PHM Canada, and Canadian counterparts overseeing the Protectors and Developers Association in Canada meeting) to denounce and halt the auction of Ecuador to mining companies. Indigenous Ecuadoran lands were ceded to mining companies under a March 2019 agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that includes funding derived from future mining activities. But in response, an uprising led by the Ecuadorian Indigenous movement CONAIE-Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador in October 2019 thwarted the implementation of the IMF policies. A similar uprising began in June 2022 principally demanding a moratorium on oil and mining activities. These struggles resist assimilation efforts by both the current neoliberal government and the preceding “progressive” Pink Tide government of Correa. Solidarity from PHM-Canada and other PHM chapters, especially through capacity building and knowledge via the Ecosystems and Health working group, has been fundamental to the success in our struggles.

Health Justice and the Green New Deal

Radically restructuring our economies away from fossil fuels by means of central planning has its roots in the 1970s and nascent ecological justice movements. Beginning in 2007, “Green New Deal” (GND) was coined and consciously popularized. The GND movement, as typified by the Sunrise Movement, captured the imaginations of many by pressing for urgent responses and action to prevent “worst-case” climate change scenarios.15 Among those calling for radical social action through the GND were public health experts who had borne witness to widening health inequalities.16

Initially, the GND, with its promise of green jobs and infrastructure, seemed like the solution to our ills. However, its focus on labor and production is myopic and still overlooks a key tenet of “climate justice”: inequality at the global scale. Without a firm grounding in the principles of global solidarity, a GND for the Global North will reproduce many of the same injustices we face worldwide today. An increase in mining for the raw materials needed for new “green” technologies, as many activists and Indigenous communities have pointed out, would mean the same exposures to toxic mining and industrial processes particularly for those living and working on frontlines.17 Without a fundamental shift, the GND will continue to deny sovereignty to those least responsible for the climate crisis.18 This is exactly what is happening with lithium in the high desert shared by Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia as mining and processing deplete the water table and make life impossible.

Those who are physically closest are the ones economically benefiting the least from extractivist projects. This inversion of benefit and harm is the reality of capitalism in today’s world.

As we continue to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, we must place health, well-being, and justice at the heart of social policies that guide toward building an alternative future. A GND that follows along the capitalist development path while increasing consumption and substituting “green” forms of energy generation for fossil fuels will not reverse the ever-widening health inequalities of the last few decades.

Only by changing our relationship to the earth and prioritizing people’s well-being will centrally planned initiatives like GND successfully address the wide and complex range of social ills. For example, the mental health crisis is exacerbated by precarious work as well as pessimism about climate change. Extractivist capitalism brings hunger and toxic exposures. Our energy transition must be just globally as well as locally. We must call for climate reparations from industrialized former colonial powers as much as we campaign for green jobs.19

Reclaiming Historicity and Toward A People’s Science

Extractivism harms our health, which is tied to the health of the planet, by destroying Indigenous livelihoods, polluting and depleting water sources, increasing violence against women, denying safe and decent employment to workers, and murdering those who oppose extractivism. Those who are physically closest are the ones economically benefiting the least from extractivist projects. They bear the harm in the confined “sacrifice areas.” This inversion of benefit and harm is the reality of capitalism in today’s world.

Complementary approaches to the GND, such as the one launched by Lyla June Johnston (Diné Nation), propose that we think ahead for seven generations. Incorporating Indigenous views of water, land, and reciprocity, which are common worldwide, the Seven Generations New Deal not only limits fossil fuels but also pushes for democracy, a green economy that accounts for marginalized communities, consumption based on local food resources, and systemic changes to extend accountability for seven generations.20 Furthermore, it calls for a reemergence of Indigenous science, which has achieved sustainability for centuries.

Gustavo Esteva (1936–2022), a de-professionalized intellectual (as he used to called himself) linked to the Zapatista struggle for autonomy, explained the folly of Western science in 2000: “Academia recognized its defeat when it did not know how to interpret, foresee what is happening in this crisis, we do not know how to get out of it … people realized that what was assumed as a revealed truth, science, is not useful, is not valid, has not been fulfilled … how the categories for Indians, peasants, or marginal urban people were not applicable … the more they learned science, the less they understood what was happening in grassroots reality.”21

Faced with this, he recovers an alternative historical knowledge of struggle, of “a spontaneous action when people themselves, with their direct experience, join with scholars, and in combination, provide historical knowledge of the struggle.” Esteva also calls for a creation of new categories based on praxis in the “end of an era,” where we can “go back to our past to guess our future” and maintain historical continuity as the Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been resisting for more than five hundred years. By seeing the past, we can see the world in another way, an alternative beyond the hegemonic Western view.

We believe in the continuous creation of such historical knowledge.

Notes

- Erika Arteaga-Cruz, “Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay): Definiciones, Crítica e Implicaciones en la Planificación del Desarrollo en Ecuador,” Saude Em Debate 41, no. 14 (July-September 2017): 907–919.

- Erika Arteaga-Cruz and Juan Cuvi, “Thinking outside the Modern Capitalist Logic: Health-Care Systems Based in Other World Views,” Lancet Global Health 9, no. 10 (October 2021): e1355–1356, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00341-7.

- For direct impacts of extractivism on various regions of the world, see “Struggles Against Repression in the Struggle for People’s Health,” PHM Health and Environment Circle, accessed August 19, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fj7FK6litZ8.

- Alberto Acosta, “Extractivism and Neoextractivism: Two Sides of the Same Curse,” in Beyond Development: Alternative Visions from Latin America, ed. Miriam Lang and Dunia Mokrani (Amsterdam: Transnational Institute and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, 2013), 61–86.

- Manuel Rozental, “Colombia Election Runoff: Leftist Gustavo Petro Leads Presidential Vote But Faces Trump-Like Tycoon,” Democracy Now!, May 31, 2022, https://www.democracynow.org/2022/5/31/manuel_rozental_colombia_election_gustavo_petro?fbclid=IwAR147Uq7I0B0ciarOMnmLSz0I9GlERa-fg8kUvBugqkIdFYrndeN3etv-cA&fs=e&s=cl.

- Cuerpo – Territorio (Buenos Aires: Fundación Rosa Luxemburgo), https://rosalux-ba.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Poster-Cuerpo-territorio.pdf.

- Rachel Hardeman and J’Mag Karbeah, “Examining Racism in Health Services Research: A Disciplinary Self-Critique,” Health Services Research 55, Suppl. 2 (2020): 777–780; Oliva López Arellano et al., “Reforma sanitaria y derecho a la salud,” in Derecho a la Salud en México, ed. Oliva López Arellano, Sergio López Moreno, Alejandra Moreno (México: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, 2015), 287–305.

- Lukas Boer et al.,”Soaring Metal Prices May Delay Energy Transition,” International Monetary Fund (blog), November 10, 2021, https://blogs.imf.org/2021/11/10/soaring-metal-prices-may-delay-energy-transition/.

- Luis Maldonado Ruiz, “El Sumak Kawsay o Buen Vivir,” (PowerPoint presentation, Escuela de Gobierno y Políticas Públicas para los Pueblos y Nacionalidades Ecuador), accessed August 1, 2022, https://1library.co/document/qoonge5q-el-sumak-kawsay-o-buen-vivir-luis-maldonado-ruiz-escuela-de-gobierno-y-politicas-publicas-para-las-nacionalidades-y-pueblos-del-ecuador.html.

- Arteaga-Cruz, “Buen Viver,” 911.

- New Zealand Ministry of Justice, “Te Awa Tupua Act (Whanganui River Claims Settlement),” March 20, 2017, https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2017/0007/latest/whole.html.

- “Development Model, Extractivism, and Environment: Knitting Resistances Globally,” in Global Health Watch 6: In the Shadow of the Pandemic (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), 253–274.

- Miguel San Sebastián and Jaime Breilh, “The People’s Health Movement: Health for All Now,” Pan American Journal of Public Health 18, no. 1 (July 2005): 45–49.

- Ryan Mckenzie, “The Yasuni ITT Initiative – International Donors Fail to Deliver on Environmental Promises,” Environment 911, October 17, 2013, https://www.environment911.org/The_Yasuni_ITT_Initiative_-_International_Donors_Fail_To_Deliver_On_Environmental_Promises.

- International Panel on Climate Change, “Summary for Policymakers” in Global Warming of 1.5C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 Degree C Above Pre-industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty, ed. Valérie Masson-Delmotte et al. (Geneva World Meteorological Organization, 2018); Michael Marmot et al., “Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On,” BMJ 38 (February 2020): m693.

- Abdul El-Sayed, “The Green New Deal Doesn’t Just Help Climate. It’s Also a Public Health New Deal,” The Guardian, April 26, 2019, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/26/the-green-newdeal-public-health-new-deal; Guppi Bola, “Reimagining Public Health,” Common Wealth UK, July 3, 2020, https://www.common-wealth.co.uk/ reports/reimagining-public-health.

- Nathaniel Bullard, “Rapid EV Growth Hastens the Peak, then Fall, of Internal Combustion,” Bloomberg, June 1, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-01/when-will-gas-cars-be-phased-out-sales-peaked-and-soon-the-fleet-will-too.

- Boer, ”Soaring Metal Prices May Delay Energy Transition.”

- Anil Tiwari, “Industries Dump Chemicals into fields,” India Mongabay, June 3, 2022, https://india.mongabay.com/2022/06/industries-dump-chemicals-into-fields-pollute-ajnar-river-in-madhya-pradesh/; Maxine Burkett, “Climate Reparations,” Melbourne Journal of International Law 10 (Oct 2009), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1539726.

- “Seven Generations New Deal,” accessed August 19, 2022, https://www.sgnd.info/.

- Gustavo Esteva, “Entrevista,” Koman Ilel, streamed on December 11, 2012, YouTube video, 17:35, https://youtu.be/NfdCQR6mTPY.