Reading Body and Soul During the COVID-19 Pandemic

A Review of Alondra Nelson’s Body and Soul

By Emily Brooks

Volume 24, Number 1, Racial Capitalism

July 12, 2021

Today, the deadly costs of the United States’ racist and dysfunctional for-profit healthcare system are more glaring than ever. From doctors cutting back on SARS-CoV-2 testing in response to insurers’ inflated costs, to hospitals laying off workers in the midst of the crisis, the evidence that the nation’s for-profit healthcare system has worsened the pandemic is overwhelming.12 The costs of these failings are disproportionately born by people of color, and they are linked to other crises of violence and inequality that protestors decried throughout the summer. For example, even as COVID-19 vaccine distribution progresses, the rate of death and illness in the United States remains among the highest of wealthy nations; and Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and Native American people are dying and falling ill at significantly higher rates than their white counterparts.3 As Alondra Nelson, sociologist and recently-appointed Deputy Director for Science and Society at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), argued in an April 2020 essay, the pandemic’s devastating impact on Black communities is “a symptom of the wider, deeper social pandemic of structural inequality.”4 In this context of racialized illness and death, anti-racist and anti-capitalist models of healthcare and conceptions of health have much to offer.

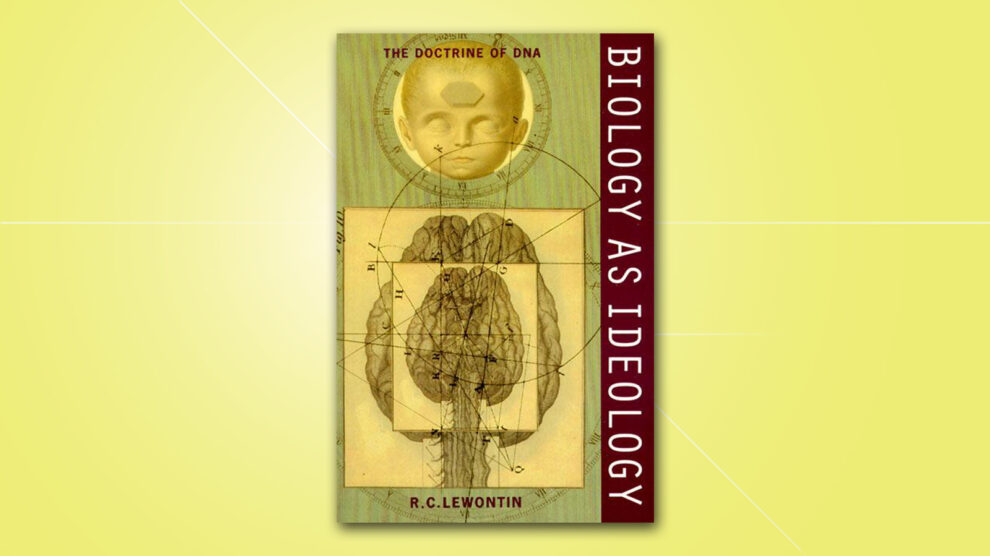

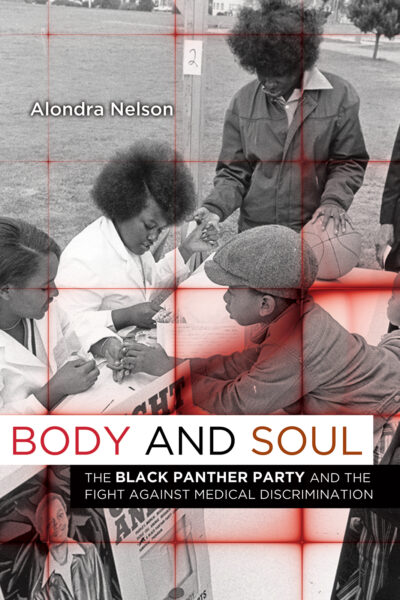

Nelson explores one of US history’s richest examples of this school of thought and action in Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination. Body and Soul argues that campaigns around healthcare and conceptions of “social health,” a politicized understanding of well-being that considers the body within society, were central to the Black Panther Party’s activism and ideology. The author is interested in foregrounding health in how we think about the work of the Black Panther Party, and re-centering the Panthers’ approach in how we consider healthcare activism of the twentieth century. Nelson places the Panthers’ activism in its historical and contemporary contexts before considering three Panther medical programs: the People’s Free Medical Clinics (PFMC), efforts to increase awareness of sickle cell anemia, and the campaign against the creation of a Center for the Study and Reduction of Violence at the University of California at Los Angeles. These case studies provide examples of the ways that Panther activists worked to expand healthcare access to medically underserved Black populations, to expose underfunding of research into diseases common in Black Americans, and to shield Black Americans from biomedical abuses. Activists grounded these campaigns in the Party’s critiques of capitalism and the racist violence of the American state.

Two themes in Body and Soul will likely be of particular interest to Science for the People readers and activists today: the provision of social healthcare for medically underserved communities at People’s Free Medical Clinics, and the role that leftist medical professionals, whom Nelson calls “trusted experts,” played in the Panthers’ health activism.5 The People’s Free Medical Clinics (PFMC), which Panther leadership mandated all current and future chapters to initiate in 1970, provided basic healthcare such as treatment for colds and flu, and testing for lead poisoning, high blood pressure, tuberculosis, and diabetes. Many PFMCs also offered immunization against polio, measles, rubella, and diphtheria.6 The healthcare at these clinics was provided by volunteer doctors with the assistance of trained Panther cadres. A central tenet of PFMCs was respecting the patients who used the clinics and valuing their experiential knowledge about their own health. Panther activists encouraged patients to challenge doctors, and physicians who mistreated patients were fired. Since PFMCs relied on the Panthers’ social health framework, they were also places where patients could receive assistance on housing issues or legal aid, similar to how some abortion funds operate today.7

The People’s Free Medical Clinics (PFMC), which Panther leadership mandated all current and future chapters to initiate in 1970, provided basic healthcare such as treatment for colds and flu, and testing for lead poisoning, high blood pressure, tuberculosis, and diabetes.

Though the clinics faced many operational challenges, examining their history today helps us imagine how access to free, anti-racist medical care in underserved communities would have transformed the United States’ experience of the COVID-19 pandemic. Today, COVID-19 is more prevalent and deadlier in Black and Brown communities than in white ones, and nonwhite residents in the US are not receiving equitable access to vaccines. Recent media attention has focused on vaccine hesitancy, rather than access, often citing a survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation that found disproportionately high rates of vaccine hesitancy among Black adults.8 Such vaccine hesitancy could be informed by the United States’ horrific history of racist medical abuses and the deadly costs of anti-Black racism in contemporary American healthcare.9 Focusing on the behavior of Black Americans, however, obscures the larger need for just access to vaccines in a trusted anti-racist setting.10 Black healthcare workers have created such spaces in cities like Oakland and Philadelphia.11 Widespread, free, anti-racist community clinics like the PFMC could have provided a preexisting network for these efforts and allowed doctors to administer vaccines within a context of ongoing social healthcare. Since COVID-19 will likely remain a problem even after this summer’s vaccination campaigns, and since capitalist modes of production continue to expand sources of zoonotic pandemics, the need for such community-based health infrastructure is only going to increase.12

Nelson notes that the PFMCs depended heavily on the relationships between Panther chapters and professionally trained “trusted experts.” These experts were generally politically active doctors who wanted to work with medically underserved communities. They volunteered their time to the medical clinics, and the Party served as a “bio-cultural broker,” linking the volunteers to communities.13 These trusted experts, however, had to support and put into practice Panther ideals, some of which undermined their own professional positions. For example, the Panthers encouraged doctors to provide medical training sessions for non-experts, thereby transferring their own technical skills to Panther volunteers and community members. Nelson argues that this practice built on the principle of “self-health” embraced by radical feminists, which challenged professionalized medical expertise.14 Trusted experts also participated in political education with Panther members to gain a fuller understanding of the group’s vision and ideology. Many of these leftist doctors and nurses connected with the Black Panther Party through their work in the Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR). MCHR was initially formed in 1963 as the Medical Committee for Civil Rights to advocate for the integration of the white-only American Medical Association.15 Members of MCHR provided healthcare to volunteers who participated in Freedom Summer in 1964, and many continued to be involved in health activism thereafter, including through work with the Panthers. The relationships between Panther chapters and trusted experts provide useful models of how leftists with relevant professional training can work with activists to advance anti-racist and anti-capitalist causes, and the example of the MCHR illustrates how networks of politically active professionals can foster and advance this work.

The Panthers encouraged doctors to provide medical training sessions for non-experts, thereby transferring their own technical skills to Panther volunteers and community members.

The crises of 2021 may provide fertile ground in which to advance similar activism. President Biden has voiced rhetorical support for racial justice, and his nominations to the Office of Science and Technology Policy, particularly that of Nelson, indicate that his administration is acknowledging the urgency of issues related to healthcare and inequality.16 Hopefully, the administration will learn from Nelson and her work and seek to meaningfully address these issues. When articulating his vision for the OSTP, however, President Biden emphasized building a “smarter and more effective healthcare system,” addressing the climate crisis by “propelling market-driven change,” and ensuring that the US is “the world leader in technologies and industries . . . especially in competition with China.”17 These priorities suggest that racial justice and health activists will have significant work to do if they hope to win real change from this administration. Understanding the Panthers’ anti-capitalist and anti-racist vision of healthcare can advance such a movement, since for-profit healthcare and medical racism are intertwined but distinct causes of sickness, death, and inequality in the United States. Any movement for equity in healthcare can founder on the shoals of for-profit health provision. As Jimmy Carter stated when asked if it was “fair” to deny poor women access to abortion through the Hyde Amendment, “there are many things in life that are not fair, that wealthy people can afford and poor people can’t.”18 When healthcare is treated as one of those commodities, Black Americans bear a disproportionate brunt of the suffering. Free and universal access to healthcare, however, must also be based in anti-racism, since racism in the provision of healthcare leads Black people and other people of color in the United States to receive worse care with deadly results. As we look toward the possibility of a post-pandemic future, Nelson’s exploration of the anti-racist, anti-capitalist vision of healthcare put forward by the Black Panther Party provides a way to imagine and fight for a healthier society.

Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination

Alondra Nelson

University of Minnesota Press

2011

312 Pages

About the Author

Emily Brooks, PhD is a Mellon/ACLS Community College Faculty Fellow and an adjunct Assistant Professor of History at LaGuardia Community College. Her book, Gotham’s War Within a War: Anti-Vice Policing, Militarism, and the Birth of Law and Order Liberalism in New York City, 1934–1945 is under contract with the University of North Carolina Press.

References

- Sarah Kliff, “Burned by Low Reimbursements, Some Doctors Stop Testing for Covid,” New York Times, February 3, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/03/upshot/covid-testing-children-pediatricians.html.

- Jessica Silver-Greenberg, Jesse Drucker, and David Enrich, “Hospitals Got Bailouts and Furloughed Thousands While Paying C.E.O.s Millions,” New York Times, June 8, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/08/business/hospitals-bailouts-ceo-pay.html.

- Joseph L. Graves Jr., “Their Money, Our Lives,” Science for the People Online, August 23, 2020, https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/web-extras/covid-19-coronanvirus-wealth-race-public-health/.

- Alondra Nelson, “Society after Pandemic,” Social Science Research Council: Items, April 23, 2020, https://items.ssrc.org/covid-19-and-the-social-sciences/society-after-pandemic/.

- Alondra Nelson, Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 6.

- Nelson, Body and Soul, 106–107.

- Zoë Beery, “What Abortion Access Looks Like in Mississippi: One Person at a Time,” The New York Times Magazine, June 13, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/13/magazine/abortion-mississippi.html.

- Liz Hamel et al., “KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: December 2020,” Kaiser Family Foundation, December 15, 2020, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-december-2020/.

- Rob Picheta, “Black Newborns More Likely to Die When Looked After by White Doctors,” CNN, August 20, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/18/health/black-babies-mortality-rate-doctors-study-wellness-scli-intl/index.html.

- Jon Hamilton, “More Black And Latinx Americans Are Embracing COVID-19 Vaccination,” NPR, March 20, 2021, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/03/20/979270516/more-black-and-latinx-americans-are-embracing-covid-19-vaccination.

- Rhea Boyd, “Black People Need Better Vaccine Access, Not Better Vaccine Attitudes,” New York Times, March 5, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/05/opinion/us-covid-black-people.html.

- Drew Pendergrass and Troy Vettese, “The Climate Crisis and COVID-19 Are Inseparable,” Jacobin, May 31, 2020, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/05/climate-change-crisis-covid-coronavirus-environment.

- Nelson, Body and Soul, 84.

- Nelson, Body and Soul, 89.

- Nelson, Body and Soul, 34.

- Sarah Kaplan, “Biden Will Elevate White House Science Office to Cabinet-level,” The Washington Post, January 15, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2021/01/15/biden-lander-ostp/.

- Joe Biden, “A Letter to Dr. Eric S. Lander, the President’s Science Advisor and Nominee as Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy,” The White House, January 20, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/01/20/a-letter-to-dr-eric-s-lander-the-presidents-science-advisor-and-nominee-as-director-of-the-office-of-science-and-technology-policy/.

- Hendrick Smith, “Carter’s Political Dichotomy,” New York Times, July 6, 1977, 22.