Review

Bleeding Rubber: Extraction as Nation-Making in Liberia

By Timothy LaRock

Volume 25, no. 2, Bleeding Earth

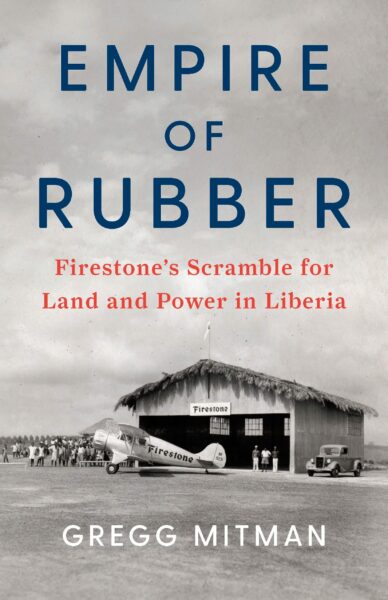

The founding of a nation is rife with complications and contradictions, from the US Declaration of Independence proclaiming “all men are created equal” while upholding chattel slavery, to post-revolution Haiti paying repartions to French slave owners after emancipation and independence. The history of the West African nation of Liberia from the early nineteenth through the mid-twentieth century is no exception. During this period, the dominant social order in the region changed from almost entirely Indigenous tribal communities, to a settler-colony populated mostly by free Black American immigrants, to a global center of rubber production dominated by white capital. Historian of science Gregg Mitman provides an accessible, compelling, and monumental account of the surprisingly American history of Liberia through his recent book, Empire of Rubber: Firestone’s Scramble for Land and Power in Liberia. In it, Mitman brings to the fore the complexity of an imperial and settler-colonial project carried out ostensibly in the name of Black freedom, as well as the complicity of the scientific establishment in the imposition of extractive scientific and industrial practices in the Global South.

A Colony of Their Own

The founding of the settler-colony of Liberia in the 1820s was intimately linked to race relations within the US homeland. The Liberian colony was established and, until its Declaration of Independence in 1847, directly supported by the American Colonization Society (ACS), a white organization that believed free Black people should move away from the United States to segregated societies, rather than be integrated into US society. The ACS was opposed by many abolitionists and free Black Americans, while supported largely by slave owners and other notable racist whites, including US Presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and James Madison, the latter of whom was the head of the organization in 1833.

The ACS saw free Black people as both threatening to the maintenance of chattel slavery in the United States specifically and a threat to white supremacy as a ruling order generally. Many of the settlers who would eventually arrive in Liberia were manumitted—meaning they were given the opportunity to be freed, but conditioned on deportation to Africa. This would not be the last time a racist regime sought to export the targets of its hatred to a settler-colony, and the strategy calls to mind the role of Nazi Germany in the Haavra Agreement of 1933, which facilitated the migration of German Jews to Zionist settlements in Palestine.

Despite ACS’s racist aims, the Black people who went to the colony were seeking independence and freedom. Yet, like the German Jews who displaced Palestinians, the founding of the colony itself required the displacement of existing people and cultures and enshrined a hierarchical racial structure. As Mitman describes, the Indigenous peoples who occupied the lands before colonization were hardly mentioned in the founding documents or considered in the laws of the country, despite the declaration of Liberia as a “home for dispersed and oppressed children of Africa” in its constitution (p. 33).1

From its earliest days, the colony had a “civilizing” mission, evidenced by Liberia’s first president, Joseph Jenkins Roberts, who described his wish to “introduce into degraded and benighted Africa the blessings of Civilization and Christianity” (p. 82). This paternalistic “civilizing” mission was shared by Harvey Firestone Sr., the founder and president of the Firestone Rubber Company (whose Akron factories were segregated and gave the most laborious and dangerous jobs to Black people), but Firestone also had one of his own: to develop an independent rubber supply for the United States. Carrying out this mission would expand the settler-colonial project of Liberia from a relatively modest export economy into an industrial-scale extractivist entrepôt.

Making an Empire in a Colony

A rubber empire cannot be built in a day. Throughout the book, Mitman emphasizes the process of land privatization out of communal stewardship and subsistence agriculture. Indigenous ways of life—for example, the use of Swidden rotation agriculture practiced by the Bassa people—were displaced by the wage relation required for industrial rubber manufacturing, which intensified throughout the early to mid-twentieth century with the establishment of large plantations.

A key figure in understanding the changing relations between people and land in Liberia was George Brown. In his book The Economic History of Liberia, Brown argued that existing relations in Liberia were not “primitive,” as Western economists claimed, but actually communal and cooperative forms of production and exchange.2 Writing in the 1930s, Brown could already see that concessions to white foreigners were destroying the very basis of the communal ways of life in Liberia.

Mitman shows how the dynamics of economic liberalization and globalization would lead Liberia down a path towards industrial extractivism, focusing on the pivotal role of white American capital.

Rubber is not indigenous to Africa. Monrovia, the future capital of Liberia named after US President James Monroe, had no rubber trees or large-scale industrial agriculture when colonists began arriving in the early nineteenth century. The early colonists slowly built an export economy through the production of palm oil and coffee, but, within a few decades, the Brazilian coffee trade and replacement of palm oil with petroleum severely hampered Liberian exports. Mitman shows how the dynamics of economic liberalization and globalization would lead Liberia down a path towards industrial extractivism, focusing on the pivotal role of white American capital in the form of the Firestone Rubber Company and its subsidiary, the Firestone Plantations Company.

Through the early twentieth century, the US rubber industry was forced to rely on British rubber supplies grown and extracted from Southeast Asia and the Caribbean. Allowing the British to control rubber prices would cause problems for American business, so, after failing to establish plantations in US occupied territories like the Philippines, Firestone Sr. turned his sights towards Liberia, which was viewed as an entry point for American capital to Africa. In the ensuing decades, Firestone would exert influence over the political, economic, and ecological conditions of the country, often with intervention by powerful friends in the executive branch of the US government.

Struggle for the Soul of Liberia

Mitman draws out the intimate relationship between the development of Liberia in the early twentieth century and questions of Black liberation and pan-Africanism. Key to this story is the famous sociologist and socialist W. E. B. Du Bois, who played a surprisingly crucial role in Firestone’s entry into Liberia. After a surveying journey to the country commissioned by US President Calvin Coolidge in 1924, Du Bois became a cautious supporter of the establishment of Firestone in the country, viewing the development of rubber plantations through foreign capital investment as a “devil’s bargain” that could allow for economic development without (white) colonization. According to Mitman, Du Bois believed that a strong and independent Liberia would “embolden and empower Black self-rule” (p. 31).

At the same time, Liberia came to play a central role in the Back-to-Africa movement of Marcus Garvey, who saw the independent nation as an entry point for creating a new Black empire on the African continent. Garvey’s movement, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), also offered capital to the Liberian government—promised from its shipping company between the United States and Africa, the Black Star Line—and sought to move its headquarters to Monrovia.

Garvey’s ambitions drew ire from both Du Bois and much of the political class of Liberia. According to Mitman, the Liberian government had decades of experience threading the needle of African diplomacy, maintaining its sovereignty and independence through uneasy and exploitative, but relatively stable, relationships with European powers and the United States. Thus, despite Garvey’s grand vision of a unified pan-African empire, Liberian leaders believed UNIA’s plans to use the country as a base from which to antagonize white European colonial powers in Africa would threaten, rather than solidify, its independence.3

Garvey and Du Bois regularly traded barbs in the press over the Liberia issue, Garvey writing in the UNIA organ The Negro World, and Du Bois in the NAACP magazine The Crisis. After an embarrassing incident in which Liberian President Charles D. B. King deported UNIA members from Liberia, Garvey became convinced that Du Bois and Liberian elites had sold the dream of a sovereign independent Liberia to the white capitalists of Firestone, calling Du Bois and the NAACP “the greatest enemies the black people have in the world” (p. 56).

The debate between Du Bois and Garvey brings to the fore an important contradiction for Liberia: between development by white foreign investment—Du Bois’s devil’s bargain—and development by Black foreign capital, like that offered by the Black Star Line. Ultimately, Liberia chose the former strategy, in part due to practicality, as Garvey and UNIA could not offer reliable funds, and were under intense political and, ultimately, criminal scrutiny in the United States. It did not help that Garvey’s aggressive and antagonistic rhetoric of class war, Black separatism, and sole domination of the African continent alienated the economic and political elite he was seeking to convince. The fact that Garvey’s vision of truly independent Black development remains difficult to imagine today, despite (or rather, because of) nearly a century of development by “economic aid” and other inventions by the Global North, shows how little the power relations between Africa and the West have really shifted.

What the Liberian working class preferred in this dichotomy is largely left untold by Mitman. The only outspoken support for Garvey came from the mayor of Monrovia, Gabriel Johnson, who was briefly named second in command to Garvey in UNIA. Johnson was quickly pressured to relinquish his UNIA position by President King, and Mitman reports that public opinion eventually moved against Garvey and those who invested in UNIA’s scheme.

As for Du Bois, despite his early support, over the years he would become one of Firestone’s most vocal detractors. After discovering that Liberia was in actuality paying 17 percent interest on development loans, compared to the 7 percent that was agreed, Du Bois wrote a ferocious critique of imperial policy towards Liberia for Foreign Affairs in 1933.4 Soon after, at a meeting with the acting US Secretary of State, Du Bois expounded upon the exploitative financial practices that kept poor countries poor through the promise of development:

Loaning money to small countries, encouraging them to buy and spend beyond their ability to pay, finding or inventing moral excuses for intervention, and then taking charge of the country in the name of some white country and in the interest of commercial organizations whose chief and only object is profit. (p. 154)

Destructive Science

In the mid-1920s, the rise in prominence of eugenics in the United States also meant that racist “scientific” practices were brought to Liberia to serve the interests of white capital. During a Firestone-funded expedition, Harvard anthropologist George Schwab, assisted by Yale-trained doctor George Way Harley, developed a categorization of the people in each of the Indigenous tribes they encountered, evaluating their “sensitivity to pain, capacity for smell and taste, conception of truth, sense of loyalty, humor, and intelligence” based on “Anthropometry,” a technique for measuring human physicality that justifies racist social orders (p. 96). In this case, the express purpose of the classification was to predict the amount of “value” members of each Indigenous group might bring to Firestone as laborers, a technique translated in time and space from the slave plantations of the US South to the segregated, wage-labor plantations of Liberia.

Firestone Company, with the support of the Liberian government, would go on to use the anthropometric classification as a basis for negotiating quota agreements with tribal leaders to send laborers to work for the company in exchange for monetary compensation based on the number of workers provided. These quotas brought accusations of forced labor against Firestone, but the company was shielded by the Liberian government, whose own practice of using forced labor for public works projects served as convenient cover for Firestone’s exploitative terms.

Medicine was also implicated in the colonial exploitation of Black Liberians by white foreigners. Through cozy relationships with Firestone, Harvard researchers from the School of Tropical Medicine were given wide-ranging access to studying disease in Liberia, both within the company and across the country. Interventions in the health of Liberians, even when cast in humanitarian terms, were almost always in the interest of industry. A healthy populace meant healthy laborers, which in turn meant healthy profits for Firestone.

Firestone doctors saw Liberians as “reservoirs for tropical disease,” especially malaria, which threatened not only their ability to work for the company, but also the white minority plantation management, whose lack of previous infections made them especially vulnerable to illness and death. This led Firestone to force inoculation on healthy plantation workers, especially domestic servants who were most likely to come into contact with the same mosquitoes as white bosses and their families. As Mitman explains, “Daily chemical cleansing of the blood of Black servant bodies with plasmoquine, a drug considered ill-advised for routine use by the Office of the Surgeon General of the US Army, subjected Liberian domestic workers to long-term toxic exposures solely for the protection of white personnel” (p. 204).

Throughout the sprawling history of indignities and oppression, there are also stories of resistance. Mitman documents multiple labor strikes by Firestone workers, including both factory workers in Akron—who attempted to join the Industrial Workers of the World around 1913, but would not form a recognized union for another two decades—and the mistreated rubber tree tappers in Liberia, who were mostly Indigenous laborers. Between 1945 and 1950, the plantation laborers rose up multiple times, drawing violent suppression by Firestone and the Liberian government.5 According to Mitman, after a drawn out battle the strikers won only a 40 percent increase in wages, up to 28 cents per day, while a long list of other demands for improved working and living conditions were ignored.

Such rich historical contexts provided by Mitman’s careful tracing of contradictions and struggles may help us grapple with the contemporary woes of Liberia in particular, and oppressed people across the world in general. After decades of civil war, Liberia is still striving to live up to its promise as an independent Black nation, but its route to liberation remains restricted by reliance on foreign, and in particular, US capital investment and economic aid.6 US imperialism continues to shape the world today, and settler-colonialism defines political, economic, and social relations from Palestine to Puerto Rico. Further, though the particular commodities may be changing, the role of science and technology in extractivist projects remains, for example, in the scramble to extract lithium and other minerals from countries in the Global South to quell the ever-growing demand for batteries and computer chips in the West. What can scientists do to resist the ecological destructruction wrought by science for profit, both from within and outside of science? What paths exist towards true liberation from colonialism and imperialism in Liberia and across Africa? There is no simple truth, but we may yet find some clues from cogent elucidations of history.

Empire of Rubber: Firestone’s Scramble for Land and Power in Liberia

Gregg Mitman

The New Press, 2021

336 pages

Notes

- Later, in 1905, the Liberian government sought to integrate (“Westernize”) Indigenous tribes by giving tribal leaders official government positions in a move to protect the hinterlands from encroachment by European colonial powers.

- Greg Mitman, “George Brown, LSE, and Liberia,” London School of Economics (blog), July 13, 2022, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsehistory/2022/07/13/excerpt-george-brown-and-firestones-liberian-empire-of-rubber/.

- Walter Rodney would later argue in his classic 1972 work How Europe Underdeveloped Africa that this line of thinking was a symptom of the material non-independence of Liberia from European colonialists. See Walter Rodney, “Colonialism as a System for Underdeveloping Africa,” Verso Books Blog, August, 10, 2010, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/4810-colonialism-as-a-system-for-underdeveloping-africa.

- W. E. B. Du Bois, “Liberia, the League and the United States,” Foreign Affairs, July 1933, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/liberia/1933-07-01/liberia-league-and-united-states.

- Liberian President Tubman was an independent rubber grower himself and so had a personal interest in quelling labor unrest. Tubman also enlisted help from the US government in labor disputes, which was more than happy to oblige in the name of anti-communism.

- Jonathan Paye-Layleh, “Liberia Marks Its Founding and Independence amid Challenges,” Associated Press, July 26, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/africa-west-liberia-b5523d87e5242a012357ceaede36dae3.