Heading for the Last Roundup

The Saga of Glyphosate and What It Means for the GMO Science Wars

By Edward Millar and Cliff Conner

Volume 25, no. 1, The Soil and the Worker

In 1962 the publication of a book entitled Silent Spring touched off a revolution in the way many humans of the industrial age perceive our place in the natural world. The book helped accelerate the worldwide environmentalist movement and forced a thoroughgoing reconsideration of the role of science in human affairs.

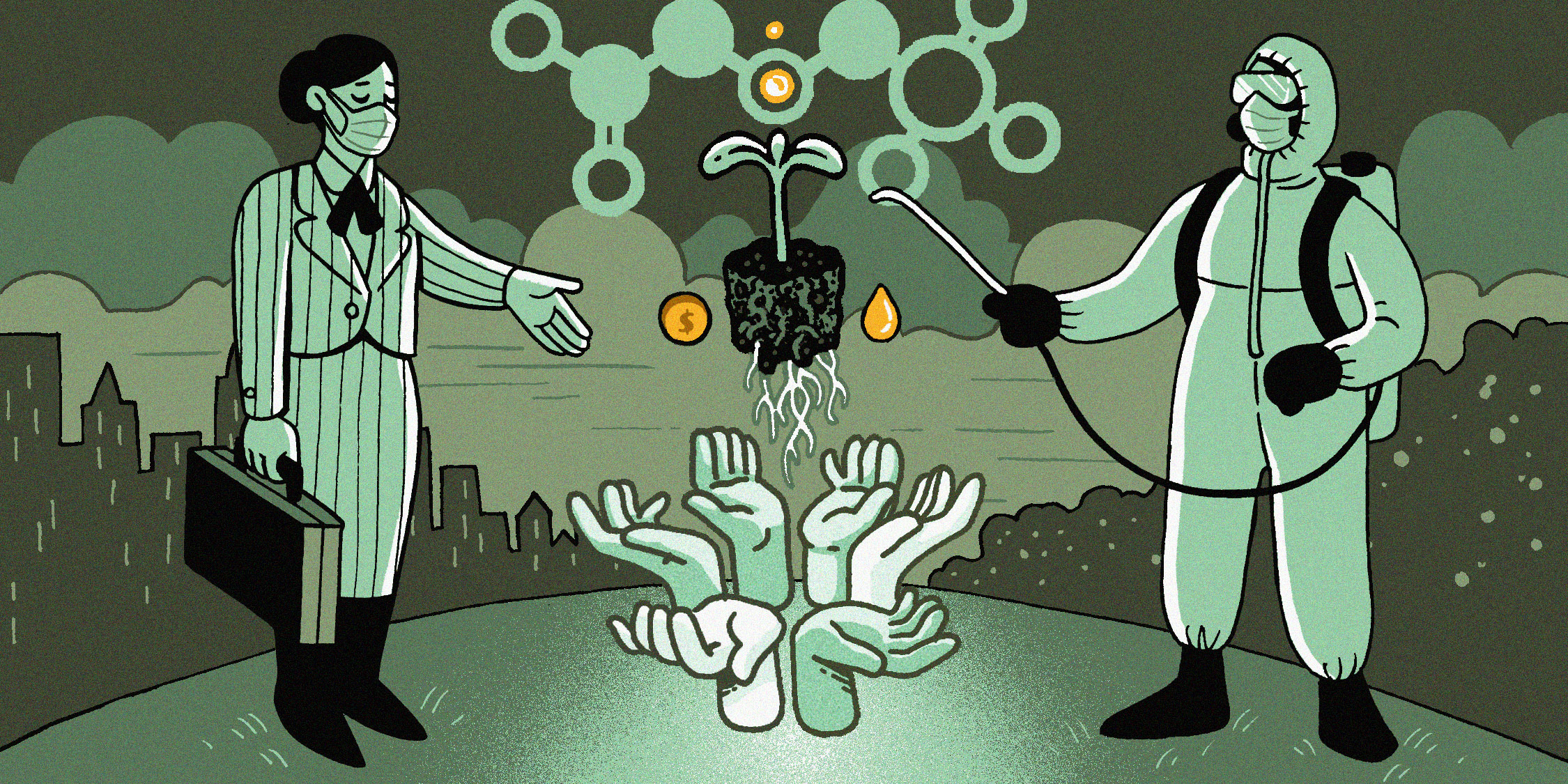

Its author, Rachel Carson, warned that the massive modern use of pesticides and other synthetic chemicals to produce food poses a serious threat to humankind and, ultimately, to the continued existence of life on Earth. Although her intended message was not explicitly anti-capitalist, by linking an impending environmental crisis to the blind drive for profits by agribusiness and the chemical industry, Silent Spring issued a fundamental challenge to the capitalist mode of food production. Not surprisingly, the industries she targeted launched a ferocious counterattack against her book.1 That assault was a major catalyst of bitter scientific disputes that continue to afflict the public discourse in the United States.

From DDT to Glyphosate

Silent Spring alerted the world to the dangers of one particular chemical pesticide: dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, or DDT. Although its use was banned in the United States in 1972, other hazardous agricultural chemicals have rapidly proliferated and efforts to regulate them have not generally been successful. Today, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) lists tens of thousands of industrial chemicals that fall under the jurisdiction of the Toxic Substances Control Act, fewer than one percent of which have been independently tested for safety (much less in combinations).2 Unfortunately, the EPA’s de facto guiding principle is that a substance is safe until proven unsafe, so the untested remainder are designated GRAS—“Generally Regarded As Safe.”3

The inadequacy of the regulatory agencies’ enforcement of safety standards leaves the public with only the courts as protection against dangerous industrial chemicals. But environmental lawyer and activist Carol Dansereau compares her twenty-eight years of experience defending the public from pesticides and other toxins to playing Whack-a-Mole: “No matter how many times we whack problems down, others pop up to take their place.”4 Among the tens of thousands of potential chemical hazards, a few have gained notoriety and name recognition; and one stands out above all the others in that regard: glyphosate.

“From the day genetically engineered crops were introduced, they were designed with one primary purpose in mind—to withstand treatments of glyphosate.”

Glyphosate, Monsanto, Roundup, and GMOs

Glyphosate is the active ingredient in Monsanto’s (now Bayer AG’s) popular weed killer brand-named “Roundup.” As “the most heavily used agricultural chemical in history,” glyphosate demands special attention.5 Another major reason why the chemical is central to current controversies over agricultural science is its place at the heart of the dispute over genetically engineered crops. The safety of genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, ranks among the most vociferously debated issues in the public understanding of science and public engagement in science governance.6 The massive global market for genetically engineered Roundup-Ready crops reveals how glyphosate is inextricably linked to questions about GMO safety. Investigative journalist Carey Gillam explains:

Shadowing the controversy over genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is what I believe to be the true health and environmental calamity of modern-day biotech agriculture—the flood across our landscape of the pesticide known by chemists as glyphosate and by the rest of us simply as Roundup. From the day genetically engineered crops were introduced, they were designed with one primary purpose in mind—to withstand treatments of glyphosate… Then and now, most of the genetically modified crops grown in the world carry the glyphosate-tolerant trait.7

That “glyphosate-tolerant trait” is the key to understanding how Monsanto came to dominate not only the agricultural chemicals market but also the global market for crop seeds. By contractually linking its weed killer to its seeds, Monsanto gained an enduring pipeline of multibillion-dollar profits from combined sales of seeds and herbicide.8

An Extremely Clever Technological Gambit

The backstory is fascinating. During the American war on Vietnam, Monsanto was the US military’s leading supplier of Agent Orange, a defoliant consisting of the chemicals 2-4-D and 2-4-5-T. Initially claiming that the herbicide posed no threats to human health, the company became embroiled in lawsuits and controversy when it was discovered that Agent Orange contained the toxic substance dioxin. By the 1970s, the company was eager to rebrand. After introducing Roundup in 1974, Monsanto reaped superprofits from the monopoly its patent provided.9 But Monsanto’s patent was due to expire in the year 2000, and the company rued the thought of having to share its golden goose with competitors. Monsanto’s scientists devised an ingenious technological solution to the problem. They would genetically engineer new breeds of Roundup Ready crops that could withstand the herbicidal effects of glyphosate.

Whereas cumbersome, labor-intensive methods of herbicide application had previously been necessary, Monsanto’s new GMO seeds provided a seemingly miraculous one-step process that would kill the weeds but spare the crops. “Use of glyphosate has skyrocketed in the past twenty years,” Gillam explains:

[Monsanto] introduced glyphosate-tolerant soybeans, corn, canola, sugar beets, and other crops, linking its new crop technology to its older chemical agent. Genetically engineered alfalfa, a common food for livestock, is also regularly doused with glyphosate now.10

Farmers loved Roundup. Glyphosate was a singularly effective weed killer, and Monsanto promoted Roundup as far safer for human health than all previous herbicides. Roundup proponents have coyly hinted that although drinking Roundup is not recommended, it probably would not damage human health.11

But—and there is always a “but” —if Monsanto’s safety claims seemed too good to be true, it is because they were not true. The brilliant technological gambit utilizing transgenic techniques to create glyphosate-immune crops has a literally fatal flaw: it kills people.

The Case of Dewayne Johnson

As a groundskeeper for a California school district, Dewayne “Lee” Johnson would outfit himself in protective equipment before strapping on his spray tank backpack and heading out to douse the schoolyards with a mix of Roundup and another Monsanto glyphosate-based herbicide, Ranger Pro. Although Johnson was skeptical of claims that the weed killer was safe enough to drink, he was reassured by the company’s messaging and not initially concerned about a workplace accident that left him soaked in the foamy mixture. Months later, scaly lesions started to appear on his body; and he was diagnosed with mycosis fungoides, a rare type of a suite of cancers known collectively as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL).

Johnson started to wonder about a possible connection between his cancer and his accident, and he called a Monsanto company hotline to ask whether this was a known risk of working with these weed killers. He didn’t hear back from the company, and he continued his groundskeeping work until a second accident resulted in the same herbicide mixture leaking down his back and neck. With his condition worsening, Johnson contacted a law firm that had posted an advertisement seeking plaintiffs for a mass tort case against Monsanto.

Monsanto did indeed have knowledge of evidence that exposure to Roundup can cause a number of deadly diseases, most notably non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Johnson’s case, as the first lawsuit to allege that occupational exposure to glyphosate-based herbicides could have fatal consequences, has received singular attention in the media; but his story is only one of many. As of March 2022, Monsanto had been confronted with more than a hundred and thirty thousand lawsuits from plaintiffs charging that its weed killers had caused them to develop NHL and other cancers. Elias de la Garza, a migrant farmworker and landscaper living in Texas, pinpoints exposure to Roundup as the cause of his NHL. Jack McCall, a farmer who died of NHL in 2015, was a self-identified “hippie” who stayed healthy and avoided all pesticides—except for Roundup, which he was led to believe was “as safe as table salt” in marketing materials that advertised its exceptionally low toxicity.12

Farmworkers and landscapers are not the only people who claim a link between their worsening health conditions and Monsanto’s pesticides. As the daughter of migrant farmworkers, Joselin Barrera believes that growing up in an environment where Roundup was used regularly is the reason she developed NHL at age 24. Sofia Gatica, a working class mother who lived near the soybean farms of Ituzaingó, Argentina, formed an anti-pesticide advocacy group after her daughter died of kidney failure. Gatica, who has been threatened at gunpoint and told to “stop messing with the soy,” believes that the indiscriminate spraying of glyphosate on GMO soy fields in Ituzaingó “is a hidden genocide, because they poison you slowly and silently.”13

Although Lee Johnson and the others would not know this until much later, Monsanto did indeed have knowledge of evidence that exposure to Roundup can cause a number of deadly diseases, most notably NHL. In the past thirty years, the rate of NHL has increased globally, with farmers facing elevated risks of this type of cancer. Researchers working with data collected by the National Cancer Institute on farmers with NHL in the United States heartland discovered possible links between NHL and glyphosate, while a 2001 Canadian study also found that frequent use of glyphosate was associated with a higher risk of this specific form of cancer. NHL is far from the only health concern regarding glyphosate; a French regulatory agency summarized others: “genotoxicity, long-term toxicity and carcinogenicity, reproductive/developmental toxicity and endocrine disrupting potential.”14

Junk Science

Rather than mobilizing its scientific resources to investigate the toxicity problem and try to resolve it, Monsanto chose instead to cover it up with a vigorous campaign of denial. It followed the tobacco industry’s playbook by manipulating scientific studies to manufacture doubt about the claims of its critics. Meanwhile, millions of Americans continued to be exposed to Roundup and many undoubtedly suffered and died unnecessarily.

The early studies indicating links between glyphosate and NHL were alarming, but inconclusive. That glyphosate posed a significant risk of cancer in humans was not a consensus view, and the company exploited the climate of doubt to promote studies that took a favorable view of glyphosate as authoritative.

In 2015, a prestigious United Nations–affiliated health agency, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), designated glyphosate as “a probable carcinogen in humans,” and “found a particular association between glyphosate-based pesticides and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.”15 When the IARC issued its findings, the group’s credibility posed a significant public relations problem for Monsanto.

Monsanto’s denials that it knew about the potential dangers of glyphosate have been proven false by evidence that has come to light in recent years when public-interest litigators took the company to court and gained access to its internal communications.

Email communications from Monsanto staff revealed how the company launched a massive behind-the-scenes campaign to discredit the IARC and its allegations. Tipped off by the EPA before the IARC published its findings, Monsanto quickly began working on counter-messaging about the product’s classification as a likely carcinogen. The company’s chairman made public statements smearing the scientists as meddlesome activists peddling politically motivated “mischief” and “junk science.”16 The company planned to spend over $200,000 on a public relations campaign to discredit the IARC, working with agrochemical industry lobby groups to write letters to officials at the World Health Organization and regulatory agencies around the globe.

“Cozy” only begins to describe the relationship between Monsanto and the regulators. The company’s internal communications indicate that a telephone conversation took place between a Monsanto employee and an EPA scientist, Jess Rowland, during which Rowland told Monsanto that he would help to block a planned review of the evidence concerning glyphosate’s safety. Rowland was also asked by Monsanto if he would help the agency “correct the record” about the IARC study and was sent documents to guide the EPA’s responses to media inquiries.17

Email communications also reveal how Monsanto’s chief of regulatory science, toxicologist William Heydens, explained to his colleagues how “ghost-writing” research articles for leading scientific journals works: they could pay nominally independent scientists to “have their names on the publication,” but Monsanto would actually be “doing the writing” and the authors “would just edit [and] sign their names, so to speak.” Heydens’ emails suggest that ghost-writing is not an atypical strategy for handling the company’s public relations concerns, and they go on to identify some prominent research papers that were written by Monsanto employees or affiliates. Notably, at least one ghost-written paper has been cited by the EPA as compelling evidence attesting to Roundup’s safety.18 This was but one of several ways the company corrupted science to defend its profits in disregard of public health.

The length to which Monsanto would go to spin the science and influence public perception about the safety of their products is evidenced by their efforts to discredit the journalist Carey Gillam. Following the publication of her book Whitewash in 2017, a spreadsheet circulated online with details about Project Spruce, the name given to Monsanto’s campaign against her. Tactics included manipulating search engine results to amplify negative reviews of her book, engaging regulatory agencies to counter her claims, and drafting scripts and talking points for company-friendly “pro-science third parties.” Further reporting uncovered the existence of the company’s “internal intelligence fusion center” with a “team responsible for the collection and analysis of criminal, activist/extremist, geo-political and terrorist activities affecting company operations across 160 countries,” including analysts monitoring “physical, cyber and reputational risk.” The company even maintained dossiers keeping close watch on the musician Neil Young after he released his 2015 album The Monsanto Years.19

| The award-winning investigative journalist Carey Gillam has written two books on glyphosate safety and the corruption of risk assessments, and has extensively covered this issue for the environmental justice outlets Undark and US Right to Know. Whitewash provides an account of the growing body of evidence that points to the manifold harms that glyphosate poses to human and environmental health, drawing from decades of research (much of which has only been made public through leaked documents), as well as interviews with farmers, scientists, former government employees, and activists. The Monsanto Papers, Gillam’s follow-up, zeroes in on a landmark court case that took place in California in 2018, the first of thousands of similar lawsuits filed on behalf of American landscapers, farmworkers, and their families who alleged that Monsanto failed to warn them of glyphosate’s dangers.

|

GMOs: “Generally Regarded As Safe”?

The scientific establishment in the United States has for many years embraced the essential safety of GMOs as an article of faith, and has tried to dismiss GMO opponents as fringe elements akin to creationists and climate change deniers. That attitude had been bolstered by the official pro-GMO positions of the premier organizations of American scientists—the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.20

However, the story of glyphosate reveals the degree to which the science behind risk assessment is corrupted by corporate interests, and the extent of the collusion between regulatory agencies and the companies they regulate. The EPA, United States Department of Agriculture, and United States Food and Drug Administration have all been criticized for maintaining a “revolving door” relationship between industry and regulators, with Monsanto employees moving back and forth between leadership positions at the company and government appointments. A probe from the United States Government Accountability Office found that between 2006–2007, EPA scientists drafted thirty-two chemical risk assessments; following political interference, only four of them were entered into the agency’s Integrated Risk Assessment System program. Published interviews with EPA scientists suggest a climate of fear, intimidation, and meddling from agribusiness lobby groups like CropLife International, which donate millions of dollars to electoral campaigns for Congressional members who sit on relevant subcommittees.21

The leaked internal Monsanto documents remind us that the science of glyphosate safety is only “unsettled” because it has been continually and deliberately blocked. It is an example of agnotology, the deliberate manufacture of ignorance as a strategy to keep the science unsettled.22 For instance, the EPA does not study the risks of exposure to Roundup, only its active ingredient. But farmworkers, landscapers, and others whose work requires them to use herbicides do not use glyphosate in isolation; they use it in commercial mixes which also contain surfactants like polyethoxylated tallow amine (POEA) and antifoam compounds. Those working with formulated commercial herbicides lack any meaningful safety data about the products they use, and some research suggests that combining glyphosate with other chemicals can intensify health risks.23

These gaps in glyphosate risk assessments should be situated in relation to a broad context of the “structural ignorance” produced by public authorities and governing bodies responsible for tracking and regulating links between chemical agricultural treatments and environmental health. In California, the regulatory framework for surveilling occupational pesticide hazards systematically underreports poisonings experienced by farmworkers. The state’s Pesticide Illness Surveillance Program (PISP) relies on a passive risk assessment procedure based on forecasts rather than actual results, and implicitly frames workplace pesticide poisonings as the outcome of discrete accidents, human error, or farmworkers’ failure to follow safety protocols. In adopting this paradigm, which assumes that pesticides are safe if used correctly, the PISP puts the onus on workers to disclose “accidents” to their employers. Undocumented migrant workers experience even greater difficulties challenging both their employers and the state about workplace safety issues, resulting in even larger knowledge gaps about pesticide risk.24 In such a data-poor environment, it is easier for corporations to exert pressure on regulatory agencies and to tilt regulations to favor their interests.

A Prolonged Battle

As previously noted, the only recourse for those harmed by exposure is through the courts. At first glance, Dewayne Johnson v. Monsanto Company reads like a success story. In 2018, the jury sided with Johnson and awarded him the full compensation sought by his legal team: $39.2 million in compensatory damages and $250 million in punitive damages. The verdict also came at an inopportune time for Monsanto, which was then negotiating a $64 billion sale of the whole company to Bayer, the German pharmaceutical corporation.25

After the verdict, Monsanto immediately filed a motion to appeal the judgment. The judge upheld the verdict, but reduced the punitive damages owed to $78 million. Further appeals have prolonged the process; and although they have all sided with Johnson, the appeals process has further reduced the sum of his settlement to $20.5 million, which he eventually received in late 2020.26 After paying out his legal fees, Johnson ended up with $10 million, a sizable sum that has allowed him to cover the medical treatments keeping him alive, but a far cry from the initial $289.2 million settlement that made headlines in 2018.27

In 2018, the Bayer acquisition was completed. The Monsanto name was officially retired, but products like Roundup and Ranger Pro remained on the shelves without warning labels. Facing tens of thousands of other plaintiffs who had filed lawsuits over the carcinogenicity of Roundup, in 2020 Bayer agreed to pay between $10.1 and $10.9 billion to settle almost a hundred thousand of the claims. The company threatened to file for bankruptcy if it could not stop the Roundup litigation.28 The company has thus been dealt a substantial, but nonfatal, financial blow by the courts. However, the revelations of its duplicity and the proven dangers of the chemicals have deeply affected Bayer’s ability to convince the public and regulatory agencies worldwide of the safety of their products, and have opened the door for continued legal suits in the future.

In July 2021, Bayer announced that starting in 2023 it would phase out the sale of Roundup for residential use, but that the product would remain available for agricultural use. Despite settling almost one hundred thousand Roundup lawsuits, the company continued to insist that no scientific evidence proves its herbicides to be carcinogenic. Perhaps most troubling is that the EPA continued to support its claim that glyphosate doesn’t cause cancer.29

Conclusion

Bayer’s multibillion-dollar payout is a tacit admission of glyphosate’s culpability in causing NHL, which completely undermines the American scientific establishment’s longstanding refusal to confront the issue of GMO safety. The carcinogenicity of a chemical that is so closely linked to the main category of transgenic crops is too blatant to be ignored due to the extent of exposures.

The evidence of the danger that Roundup poses to workers, and of the corruption of science by corporate influence, solidifies the case that oversight of agrochemicals and GMOs alike must be governed by the precautionary principle, which requires that in instances of “unsettled” science, we must err on the side of public and environmental health, rather than on the side of profit margins for multinational agribusiness conglomerates.30 Furthermore, regulatory agencies must have the power to not only issue directives, but to enforce them. Toothless safety regulations are worthless.

There has been a tendency for some on the left to cede the issue of health and safety to GMO proponents, or to downplay the importance of worker and consumer safety in relation to the broader fight against capitalist agribusiness. As one example, Richard Lewontin argued that GMO safety is the “wrong target,” and that the true dangers of transgenic modification come from the escalation of capital-intensive industrial agriculture across the planet.31 The evidence about the links between glyphosate and NHL should cause us to reassess the assumption that safety can be considered independent of political economy, especially in cases where genes have been modified to encourage exponential increases in the application of a harmful herbicide. Questions about environmental health and safety of GMOs should not and cannot be disentangled from the political economy critiques of agriculture under global capitalism. Framing concerns about GMO safety as consumer battles waged in the grocery store aisles diverts attention from the threats to both the worker and the soil. Agricultural workers and landscapers face the greatest risk from a regulatory system designed to balance health concerns against economic ones, weighted strongly in favor of profit.

Growing evidence about the emergence of superweeds and the threats to pollinators add further urgency to the need to redesign the global food system according to fundamentally different principles and practices.32 Global agriculture must be de-commodified and reconstructed based on the philosophy of agroecology, which resists resource-intensive approaches like monocropping, pesticides and genetic engineering, and instead treats farming as the nurturing of complex and mutually beneficial ecological relations.

Notes

- John M. Lee, “‘Silent Spring’ is Now Noisy Summer,” New York Times, July 22, 1962, https://www.nytimes.com/1962/07/22/archives/silent-spring-is-now-noisy-summer-pesticides-industry-up-in-arms.html.

- Clifford D. Conner, The Tragedy of American Science: From Truman to Trump (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020), 87–88.

- See Sheldon Krimsky, “The Unsteady State and Inertia of Chemical Regulation Under the US Toxic Substances Control Act,” PLoS Biology 15, no. 12 (December 2017): e2002404, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2002404.

- Carol Dansereau, What It Will Take: Rejecting Dead Ends and False Friends in the Fight for the Earth (CreateSpace, 2016), 349.

- See Douglas Main, “Glyphosate Now the Most-Used Agricultural Chemical Ever,” Newsweek, February 2, 2016, http://www.newsweek.com/glyphosate-now-most-used-agricultural-chemical-ever-422419.

- See Brian Wynne, “Creating Public Alienation: Expert Cultures of Risk and Ethics on GMOs,” Science as Culture 10, no. 4 (2001): 445–481, https://doi.org/10.1080/09505430120093586.

- Carey Gillam, Whitewash: The Story of a Weed Killer, Cancer, and the Corruption of Science (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2017), 1–2.

- “Monsanto brought in more than $2 billion per year from its herbicides . . . and more than $10 billion more per year from its seed business.” Carey Gillam, The Monsanto Papers: Deadly Secrets, Corporate Corruption, and One Man’s Search for Justice (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2021), 214.

- Gillam, Whitewash, 26.

- Gillam, Whitewash, 3.

- Gillam, Whitewash, 13–14; Gillam, Monsanto Papers, 9, 176.

- Gillam, Monsanto Papers, 17–19; Whitewash, 9, 15; Ronald V. Miller, “Monsanto Roundup Lawsuit Update,” Lawsuit Information Center, March 12, 2022, https://www.lawsuit-information-center.com/roundup-mdl-judge-question-10-billion-settlement-proposal.html.

- Gillam, Whitewash, 15, 155, 157.

- Quoted in Gillam, Monsanto Papers, 127; Gillam, Whitewash, 86, 89.

- Gillam, Monsanto Papers, 53.

- Quoted in Gillam, Whitewash, 97.

- Gillam, Whitewash, 103, 225.

- Gillam, Monsanto Papers, 71-72, 79.

- “Project Spruce: Carey Gillam Book,” Baum Hedlund Law, created 2017, https://www.baumhedlundlaw.com/documents/pdf/monsanto-documents-2/mongly08179950.pdf.; Carey Gillam, “I’m a Journalist: Monsanto Built a Step-By-Step Strategy to Destroy My Reputation,” The Guardian, August 9, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/aug/08/monsanto-roundup-journalist-documents; Sam Levin, “Revealed: How Monsanto’s ‘Intelligence Center’ Targeted Journalists and Activists.” The Guardian, August 8, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/aug/07/monsanto-fusion-center-journalists-roundup-neil-young.

- Conner, Tragedy of American Science, 29–30.

- Gillam, Whitewash, 220, 231.

- Robert N. Proctor, “Agnotology: A Missing Term to Describe the Cultural Production of Ignorance (and its Study),” in Agnotology: The Making & Unmaking of Ignorance, ed. Robert N. Proctor and Londa Schiebinger (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), 1–36; Matthias Gross and Linsey McGoey, “ Introduction,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Ignorance Studies eds Matthias Gross and Linsey McGoey (New York: Routledge, 2015), 1–14.

- Whitewash, 79–80.

- Francois Dedieu, Jean-Noël Jouzel, and Giovanni Prete, “Governing by Ignoring: The Production and Function of the Under-Reporting of Farm-Workers’ Pesticide Poisoning in French and Californian Regulations” in The Routledge International Handbook of Ignorance Studies, ed. Matthias Gross and Linsey McGoey (New York: Routledge, 2015), 302, 299, 298.

- Gillam, Monsanto Papers, 305, 290, 62; The acquisition of Monsanto by Bayer brought its own controversy. A 1999 lawsuit launched by a Holocaust survivor accused Bayer of being involved with Josef Mengele’s experiments on Jewish children. Bayer’s predecessor, the conglomerate IG Farben, was the manufactuer of the gas chamber poison Zyklon B used during the Holocaust. See Edmund L. Andrews, “I.G. Farben: A Lingering Relic of the Nazi Years,” The New York Times, May 2, 1999, https://www.nytimes.com/1999/05/02/business/the-business-world-ig-farben-a-lingering-relic-of-the-nazi-years.html.

- Gillam, Monsanto Papers, 309.

- Carey Gillam, personal communication, March 22, 2022.

- “Bayer Announces Agreements to Resolve Major Legacy Monsanto Litigation,” Bayer AG, June 24, 2020, https://media.bayer.com/baynews/baynews.nsf/id/Bayer-announces-agreements-to-resolve-major-legacy-Monsanto-litigation.

- Jessica Fu, “Bayer Will Stop Selling Roundup for Residential Use in 2023, an Effort To Prevent Future Cancer Lawsuits,” The Counter, July 30, 2021, https://thecounter.org/bayer-glyphosate-products-roundup-residential-2023-cancer/.

- The precautionary principle is an ethical and legal norm that guides the European Union’s GMO regulatory policies. Its essence is that waiting for scientific certainty of negative consequences before taking action to protect human health and the environment is unconscionable. The precautionary principle has been adopted into international laws like the UN World Charter for Nature (1982), The declaration of the International Conference on the Protection of the North Sea (1987), and the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992).

- Richard Lewontin, “Genes in the Food!” in It Ain’t Necessarily So: The Dream of the Human Genome and Other Illusions (New York: NYRB Press), 362.

- Gillam, Whitewash, 189–213.