Ants Against the Grasshopper

By Nadine Fattaleh and Calvin Wu

Volume 25, no. 1, The Soil and the Worker

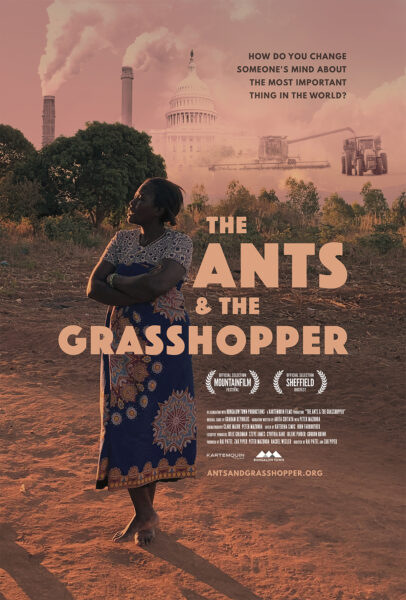

Aesop’s classic fable, “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” tells a story about the perils of shortsightedness and irresponsibility. While the grasshopper is inclined to rely on natural resources available today, the ants plan their actions long-term and diligently prepare for an uncertain season to come. In the 2021 documentary that borrows its name from the cautionary childhood tale, Raj Patel and Zak Piper reinterpret the fable for a conflict-ridden world faced with rapidly warming climate and compounding challenges to produce sustenance on scorched earth for a growing global population.

The main character and narrator of the film, Anita Chitaya, a member of the Soil, Food and Healthy Communities (SFHC) organization based in Bwabwa, Malawi, at first appears as the quintessential subject of Western developmentalism. Her image may bring to mind donor reports supporting neoliberal, market-oriented interventions in Sub-Saharan Africa along the lines of the Green Revolution. However, The Ants and the Grasshopper rejects the tyranny of international aid formulas to modernize farming; instead of bearing witness to the triad of poverty, patriarchy, and powerlessness, it inverts the narrative and confers agency to the people. The film follows Anita (along with her colleague Esther, founder of SFHC) on a journey to the United States, where they meet farmers, activists, and elected officials to discuss the lived experience of climate change amongst subsistence farmers from Sub-Saharan Africa. Beseeching a life facing threats of drought and famine, Anita insists in her travels on one central message: “If you want someone to change, you go to their doorstep with your problem—because they will be unable to ignore you.”

The problem Anita wishes to bring is simple: the United States emits 15.2 metric tons of CO2 a year per capita, compared to Malawi’s 0.087.1 Anita and the SFHC have already adopted simple and innovative technologies, from sustainable intercropping to fuel-efficient stoves that prolong firewood burns. Looking at the jet flying across the sky, she knows that to alleviate climate change, she needs to convince America to take action.

As Anita arrives in the United States, the sepia tones that dominate the visual aesthetic of village life in Malawi give way to landscapes of high modernist farming. The characters encountered throughout the journey are anything but static stereotypes of liberal environmentalism. The film features neither yoga-practicing advocates of universal veganism, nor Silicon Valley bros serving silver-bullet solutions to the climate crisis between hamburger buns. The cast is grounded in material production, from small and mid-sized family ranches in Wisconsin, to large-scale industrial operations in Iowa, to Black urban farms in Detroit, to community kitchens in segregated communities of Oakland, California. Anita’s first world interlocutors embody diverse contexts of the capitalist agricultural system.

The film’s staging of the unequal worlds, developed-underdeveloped, North-South, core-periphery, contrasts with Anita’s quip: “We should be able to sit down and talk about this.” The desire for dialogue constantly generates a process of translation, of seeing diverse realities of the climate crisis in ways that allow for the coming together of similar experiences. On encountering the machinery of capital-intensive agriculture, Anita is entranced by a tractor that tends to one thousand acres and whose cost exceeds five times Anita’s anticipated life earnings. Yet, operating at vastly different scales, workers on heavily irrigated and mechanized farms and their counterparts cultivating rainfed crops by hand share one danger whose descriptor requires no translation: debt. Debt is an objectification of the systemic force of capital (the true villain of this film) that undermines the successes of Anita’s journey.

Here, the audience witnesses another inversion. Because their farming practices have been more fully reorganized according to the logic and dynamics of industrial agriculture, the US farmers turn out to be more powerless than their counterparts in Malawi. Not for the willful dismissal of climate reality, nor callousness in the face of Anita’s pleas, they entreat, “What are we to do?” From paying off loans for the heavy machinery, to spraying ever more ineffectual Roundup to rid crops of pests, to working in a coal power plant to compensate for profit loss from organic farming, the US farmers face a stark conflict between their desire to heal the earth and the boundaries set by the capitalist food system. Some eventually make limited lifestyle changes; others resort to prayer. The entrenchment of people under the reproduction of capital limits individual choices, removes human agency, shatters imagination, and sabotages change.

Yet, Anita remains unfazed and insists that the journey is “not in vain.” Her optimism and hope have a complicated origin. In her youth, she was forced into marriage. Against all odds under a highly patriarchal society, she gradually changed her husband’s worldview and created a community for women’s collective empowerment. While her past success in teaching for change reinforces her present conviction, it is also worth noting how hope can flourish in times of desperation, whether against patriarchy or climate change.

Indeed, the message of hope becomes more pronounced as Anita arrives in Oakland, California and joins Black organizers in a community food kitchen. Amidst tent cities, polluting mills, and dilapidated neighborhoods, Anita brings the audience to the realization that not everyone in America is helplessly trapped. The people “who have no choice but to fight” have been fighting all this time. The community kitchen draws from lessons of the Black Panther Party, working with local farmers to provide healthy, home-cooked meals to undernourished people in their community. Likewise in rural Maryland, a historical heartland of white supremacy,2 Black farmers form cooperatives and seek to re-establish their severed connection to land. In Detroit, under the watchful eyes and violent arms of the police, Black residents set up urban farms to not only tackle food insecurity in their impoverished neighborhood but demonstrate the potential of regenerative harvesting.

At this point, it is abundantly clear who are the ants and who is the grasshopper. The ants cannot wait for change; they don’t need to be convinced of the urgency of confronting the climate crisis. The grasshoppers are neither certain nations or individuals but the system itself, which destroys communities all over the world. The shared lived experience of oppression bonds Anita and her various hosts together and kindles the light of international solidarity. While the film does not explicitly offer prescriptions for a path forward—and trails off to an unseen meeting with an elected official in the US government—it displays an array of localized mobilizations with inspiring personal and community transformation. This is a heartfelt tour-de-force; the film’s rare quality, in its emphasis on grassroots organizing, draws the audience toward direct action. As it turns out, the purpose of Anita’s journey transcends the naivete of “talking about the problem.” Anita presents a mirror allowing us to see that the solution is already present among the people. Instead of moralizing the problematics of helpless Third World victims in need of saving, The Ants and the Grasshopper recaptures the revolutionary agency of the oppressed.

Mainstream climate narratives typically unfold according to a few standardized scripts. Some construct a catastrophist formula in which the warming planet seems beyond human capacity for intervention.3 Others contain clearer imperatives but forward plot lines that tout ethical consumption or corporate responsibility, reinforcing faux individualist solutions.4 Patel and Piper do not escape the mainstream tropes completely. Their positive portrayal of local and organic farming leaves the audience defenseless against ongoing cooptation and systemic subsumption.5 The backdrop of patriarchy and feminism in Malawi also requires a much deeper historical and political understanding lest the audience falls prey to cultural relativism.6 And the contrast of “different worlds” ignores the active process of globalization and imperialism as the prima facie causes of uneven geography.7 Nevertheless, the core messages of urgency, solidarity, and hope are gravely needed in our present conjuncture.

One of the timeless qualities of fables is their clarity in reflecting the human condition. They plant seeds in our consciousness; then, to cultivate the seeds of social change, we hope that the audience takes action upon viewing the film.

For further reading

The Red Deal: Indigenous Action to Save Our Earth

The Red Nation

New York: Common Notions

2021

176 pages

A People’s Green New Deal

Max Ajl

London: Pluto Press

2021

224 pages

Notes

- Emission data in 2018. See “CO2 Emissions (metric ton per capita): 1990-2018,” The World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.PC.

- Brian Palmer, Sam Weber, and Connie Kargbo, “Maryland reckons with a Violent, Racist Past,” PBS News Hour, June 19, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/maryland-reckons-with-a-violent-racist-past.

- Graham Readfearn, “David Attenborough Netflix Documentary: Australian Scientists Break Down in Tears Over Climate Crisis,” The Guardian, June 3, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jun/04/david-attenborough-netflix-documentary-australian-scientists-break-down-in-tears-over-climate-crisis.

- Peter Bradshaw, “2040 Review – An Optimist’s Guide to Saving the World,” The Guardian, November 7, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/nov/07/2040-review-an-optimists-guide-for-how-to-save-the-world-damon-gameau.

- Naomi Zimmerman, “So, Is Organic Food Actually More Sustainable?” Columbia Climate School Student Blog, February 5, 2020, https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2020/02/05/organic-sustainable-food/.

- Linda Semu, “Kamuzu’s Mbumba: Malawi Women’s Embeddedness to Culture in the Face of International Political Pressure and Internal Legal Change,” Africa Today 49, no. 2 (Summer, 2002): 77–99.

- Ezequiel Burgo and Heather Stewart, “IMF Policies ‘Led to Malawi Famine’,” The Guardian, October 28, 2002, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2002/oct/29/3.