Cooperatives Against Capitalism and White Supremacy

Routes to Black Freedom

By Erik Wallenberg

Volume 25, no. 1, The Soil and the Worker

Black farmers today are fighting for a share of the 2021 federal stimulus package that was meant to redress generations of discrimination by banks and the government in awarding subsidies, loans, and grants. The $4 billion in debt forgiveness is now being held up by white farmers and other groups suing the government to stop the distribution of funds.1 This combination of institutional and lawyerly white supremacy has deep roots. Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. addressed this very issue in a 1968 speech while building the Poor People’s Campaign. Monica M. White reminds us that King identified the racism of white farmers who were themselves “receiving millions of dollars in federal subsidies not to farm” yet who were also “the very people telling the Black man that he ought to lift himself up by his bootstraps.”

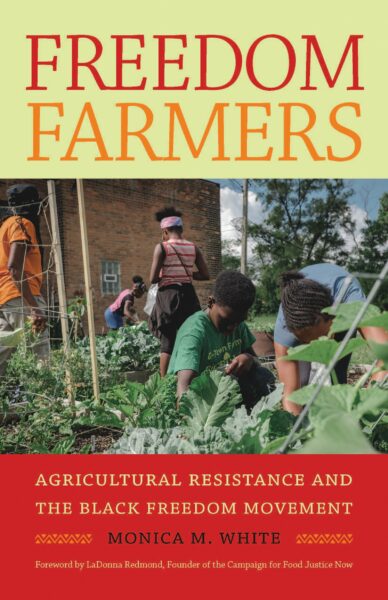

White has written a slim volume that connects, across a long timeframe, social movements of Black farmers to access land, knowledge, and materials to create farms and farming communities in the face of white supremacy. The book, Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement, jumps from the intellectuals and academics Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver, and W. E. B. Du Bois, to the 1960s cooperative movement (with a particular focus on Mississippi and Fannie Lou Hamer), and finally to Detroit and the urban farming movement of the 2000s. Viewing cooperative agriculture as a form of resistance to white supremacy, these jumps in time work to highlight moments of organizing, even as they move from South to North and from rural to urban. This approach has its drawbacks. Most notably, leaving out Black farmer organizing in the 1930s, particularly in the South, misses a significant movement. Sharecropper and tenant organizing, especially in the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, explicitly confronted white supremacy along with the power of capital, and undoubtedly shaped later movements.2

Working as a sociologist, White creates a sprawling theoretical framework that presents each of her historical cases as examples of “collective agency and community resilience” which utilize a range of practices including “economic autonomy,” “prefigurative politics,” and “commons as praxis.” In this way the book is more sociological than historical; and though she engages some archives, much of the history is drawn from secondary sources, field work, and interviews with farmers in Detroit and Mississippi.

The most exciting element of her initial chapter is her engagement with a recent biography of George Washington Carver that highlights his ecological outlook connecting people, land, animals, and the broader environment to a fulfilling and healthy life.3 White casts the well-worn debates between Du Bois and Booker T. Washington in a different light, focusing on the practicality of farming. She shows many examples of the “loving care” that motivated Booker T. Washington’s work, including the creation of traveling agricultural schools. There is some slipperiness where White shows Black farmers working to become owners of land that they rent to tenants themselves, recreating the exploitative relationship that the cooperatives of the 1960s attempted to work around. This feels like a missed opportunity to deal with the question of class, and, in particular, how Du Bois’s ideas changed over the subsequent decades as he addressed capitalism more systematically and turned from mutual aid and cooperatives to socialism and communism as key to achieving collective freedom.4

White’s interest in the topic comes from her encounter with the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network (DBCFSN) in 2006. She set out to trace some of the roots of this urban agriculture movement, wanting to bring sociological and historical perspectives to bear. Though she says she is following the descendants of those who moved out of the South in the great migrations of the twentieth century, in particular in the aftermath of the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, she doesn’t explicitly show us those connections in her interviews with individuals. She does, however, show us the work these urban Black farmers are undertaking to try and rebuild their shattered community using food and farming in the economically devastated Rust Belt.

“Our efforts to promote cooperative economics are designed in essence to get people to think beyond the logic of capitalism. But we should be clear that running a food co-op or a cooperative buying club isn’t the same thing as having state power where you can redistribute resources.”

By 2006, Detroit had only one major grocery store chain in the 140 square miles of the city, and by the following year, none. While food deserts are a common enough concept, this fact is jarring in a city of seven hundred thousand. The work of the DBCFSN goes beyond bringing food to this bleak reality. Malik Yakini, a founder of the organization, states one of their central aims is to teach about the interconnectedness of the environment, food, and human health, in opposition to epistemologies of dominion over nature that exemplify the Judeo-Christian approach to relationships between humans and the environment. The group’s mission is to build an anti-racist and anti-capitalist structure, to create collective community wealth, and to show what a different type of farming and food system might look like. As Yakini told White, “Our efforts to promote cooperative economics are designed in essence to get people to think beyond the logic of capitalism. But we should be clear that running a food co-op or a cooperative buying club isn’t the same thing as having state power where you can redistribute resources.”

Of course, building cooperatives within the confines of the capitalist economic system is full of contradictions; engagement with another well-known anti-capitalist cooperative in the South, Cooperation Jackson in Mississippi, might have illuminated ways of addressing these complexities. While White’s focus on the intentions of these urban farmers helps give a sense of their project, we have to extrapolate the contradictions for ourselves. For instance, what are we to make of the fact that the DBCFSN is sustained in part by grant money from the Kellogg Foundation and by volunteer labor?

DBCFSN is ultimately a much smaller project–with only fifty members beyond volunteers and tourists who lend a hand–than the projects White explores in the heart of the book, which takes us to the late era of the civil rights struggle starting in 1967. Freedom Farmers is more about the use of cooperatives than resistance by farmers in general. White argues that cooperatives were a complement to the active confrontation of boycotts, sit-ins, marches, and protests. The work she explores seems closer to the Black Panther Party’s health, breakfast, and education programs focused on “survival pending revolution” than active confrontation.5

As an alternative to migrating north in the face of plummeting farm prices, as well as a response to sharecropper and tenant evictions, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee member and civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer built the over six-hundred-acre Freedom Farm Cooperative in Sunflower County, Mississippi. Hamer found innovative solutions to rural poverty, creating the Pig Bank (which bred pigs and gave them away so rural farmers could multiply their own pig farms) and a housing development (which built over eighty affordable homes with electricity, running water, and sewage). Her farm was one of the first sites of a Head Start program in the region and coordinated health and dental care for hundreds of families. Much of this was made possible by federal money, a key difference with the foundation grant money that supports the much smaller Detroit project. Freedom Farm closed by 1976 in the face of natural disasters, personal crises, and, centrally, the loss of government and other funding; Ms. Hamer died of breast cancer the following year.

White follows this chapter with two more on cooperatives in Mississippi and the broader region, the North Bolivar County Farm Cooperative and the still larger Federation of Southern Cooperatives. The North Bolivar coop was formed in response to tenant farmers being evicted from their land as owners were paid subsidies by the government to leave it fallow. A reprise of the problems in the previous generation’s farm bills, this example brings us closest to moving beyond cooperatives and into union organizing. White highlights a 1965 strike by tractor drivers and a subsequent occupation of the land, including the establishment of a strike city in Mississippi, but doesn’t explore the option or debates around unionizing farmers as a strategy. Central to her argument is that these projects show what is possible, and it’s a strong point. Farmers were politicized in the process of building cooperative enterprises. Regardless of how we propose getting past the crises of capitalism, these projects all show people’s interest, willingness, and ability to organize a food system for the health and safety of their communities and the broader physical and social ecology.

The regional Federation of Southern Cooperatives provides the example of how local white supremacists in the banking and professional classes organized to deny the cooperative credit and loans, sabotaging their work. In response to racist attacks on newly integrated schools, the Federation helped organize a school boycott—a tactic more recently highlighted as a northern innovation of the movement—that lasted over a week. We get tidbits of these great examples of organizing through the early 1970s, but we don’t hear how they evolved or why the story stops there.

The final chapter leaves rural Mississippi in the mid-1970s and jumps to urban Detroit. In 1974, Detroit mayor Coleman Young created the Farm-a-Lot program to support urban agriculture as the city hemorrhaged population. Unfortunately, we don’t learn how this program evolved over the intervening thirty years, or how it shaped any of the farmers that White spends time with in the 2000s. These jumps in time throughout the book are jarring, leaving the reader with more questions than answers. White has compiled a lot of important history related to the struggles and victories of Black farmers, important players in the Black freedom struggle. The gaps that remain are a testament to the fact that she has identified an important historical trend that demands further investigation.

As LaDonna Redmond writes in her introduction, White has given us a book to demolish the “culture of poverty” arguments that blame individuals for bad choices in relation to food and health and instead shows systemic and root causes of these issues. While White has illuminated the crises that white supremacy and capitalism cause in Black food and agricultural politics, as well as the dead end of liberal solutions like food pantries and paternalism, her argument often stops at the importance of self-sufficiency. Building on White’s crucial foundation, more work is needed to explore the ways Black farmers and communities might win a food system that meets basic human needs for “survival pending revolution.”

Monica M. White

Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement

The University of North Carolina Press

2018

208 pages

Notes

- Alan Rappeport, “Black Farmers Fear Foreclosure as Debt Relief Remains Frozen,” The New York Times, February 21, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/21/us/politics/black-farmers-debt-relief.html.

- Robin D. G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990).

- Mark D. Hersey, My Work Is That of Conservation: An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

- Bill Mullen, W. E. B. Du Bois: Revolutionary Across the Color Line (London: Pluto Press, 2016).

- Huey P. Newton, To Die for the People: The Writings of Huey P. Newton (New York: Random House, 1972), 104.