Open Source Software Community Radios in Support of Popular and Indigenous Struggles in Oaxaca

By Mayu Ruiz Rull

Volume 24, Number 2, Don’t Be Evil

This is an English translation of the original article in Spanish.

Indigenous communities in Mexico are a sector of the population historically excluded with respect to access to basic services like health care, education, potable water, or electricity. Many live in isolated rural areas, accessible only by unpaved roads or on foot. Because of this, access to communication networks and technology is very limited, and the so-called digital gap is far from being closed. Owing to its simplicity and ability to overcome geographic barriers, radio has been and continues to be the principal means of communication for these populations.

The first community radios were developed in the seventies and organized by communities confronted by the need to develop their own content with open participation in places where private telecommunications companies are not financially incentivized to go. Motivated by priorities outside of market forces, the community radio model affirms the right to freedom of expression using original languages, thus strengthening the identity of the people—both their linguistic and cultural diversity. In Oaxaca, the southernmost state of Mexico where sixteen indigenous communities officially live together, the indigenous population is greater than 100,000 inhabitants, more than 32 percent of the total.1 It is the original people who, through the years, have preserved the abundant natural resources in their territories and now are held hostage by extractive multinational corporations.2 In this sense, the community radio model has a special importance in the context of constant resistance: giving voice to affected communities in the face of lack of representation and homogenization in Mexican media, which are closely linked to political caste—a reality investigated by the Media Ownership Monitor Mexico project.3

Oaxaca, 2006: Radios and Social Uprising

The importance of community radios in articulating social movements was made clear during the 2006 protests in Oaxaca, which wouldn’t have been possible without these radios. In May, 20,000 teachers of Local 22 of the National Union of Education Workers went on strike, establishing an encampment in the central public square in Oaxaca City. They demanded more resources for the union and basic support for their students. These teachers, for the most part, worked in poor and rural schools, where they often took on the role of an intermediary between isolated communities and governmental agencies. The government declined to negotiate, and at dawn on July 14th, the federal police (Policía Federal Preventiva; PFP) violently evicted the encampment. Radio Plantón, the station from which the educators were informed of the strike and heard calls for support, was also targeted by PFP. However, the coverage of the eviction by this radio inspired rapid mass mobilization from diverse sectors of the population and raised the principal demand for the resignation of the Governor, Ulises Ruiz Ortiz. In the months that followed, this and other community radios became channels of communication, transmitting the protest demands and real-time community-sourced sources of information about repressive attacks by the state against mobilizations.4

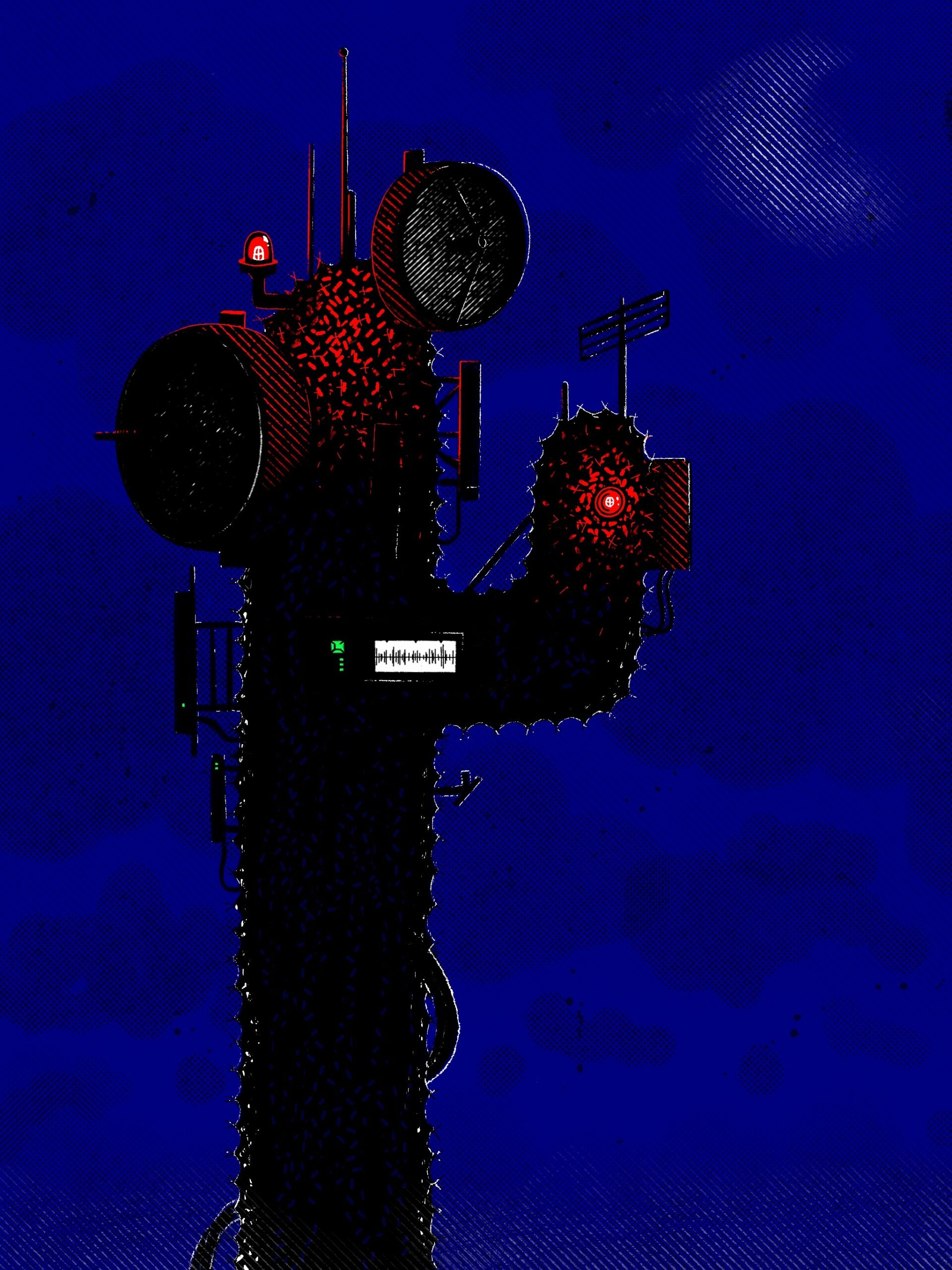

Out of the largest movement in the history of Oaxaca, in which 300,000 people — organizations, unions, civic groups, and indigenous communities — came together in the streets against repression, corruption, and authoritarianism, the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca — APPO) was created. From Radio Plantón, backed by the University Radio, the APPO organized a peaceful occupation of multiple government buildings with the goal of stopping the functioning of the government and thus forcing the dismissal of the governor. A group of women was able to take over the facilities of the state television station, Channel 9, and broadcast from there despite having been previously denied time to explain their point of view. They were indignant over the campaign of misinformation and the criminalization of the APPO by the two major television stations in Mexico: Televisa and Azteca TV. Three weeks after the takeover, the police, under cover of darkness, destroyed the transmission tower. The same night, the APPO took over twelve other radio stations.5 With these, it was able to organize self-defense measures that would follow from the intensification of state repression: during the course of the five months that the teachers strike endured, neighbors within Oaxaca erected and maintained barricades to defend neighborhoods in the face of police attacks and the deployment of the army.

The brutal repression and persecution of activists, the refusal of the government to negotiate, and the smear campaign resulted in tension among different organizations which had mobilized and division within the teachers’ movement. At the end of the conflict when twenty people had been murdered, 366 people had been detained, and 381 people had been injured, the minimum proposal by the government to comply with initial union demands was accepted, causing significant ruptures in the APPO.6

In addition to the wave of repression by the PFP, 2006 was also marked by an allegedly fraudulent national election and brutal conflict in Atenco; these events generated a popular consciousness that still lives in the collective imagination of Oaxaca and all of Mexico.7 Confronted by the biased official media coverage and after having experimented with appropriating different communication media, community radio stations found themselves in an organizing boom: those already existing were strengthened, and new initiatives were developed within a culture of popular and activist journalism that, as with Radio Plantón, continues to this day.

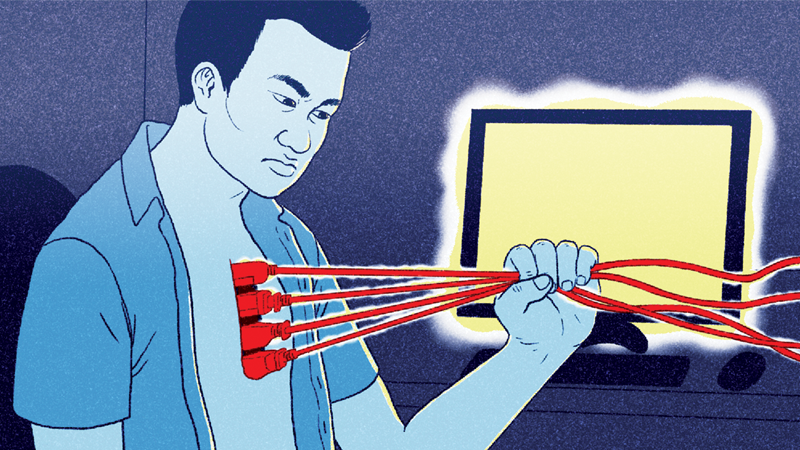

Open Source Software and Technological Adaptation by Indigenous Communities

The year 2006 was also marked by the expansion of the philosophy of open-source software. Among free and independent media driven by activists in the “punk” and liberation movement, “pirate” radio station Ke Huelga emerged from the 1999 student strike at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, contemporaneously with the anti-globalization movement. The participatory global network of independent journalism Indymedia, created during protests against the World Trade Organization summit in Seattle, helped to spread the idea of open-source software and the possibility of technological sovereignty that this opened up. With limited technological resources and almost no access to technology in general, activists searched for useful communication tools that were both democratic and outside the realm of corporatism and private enterprise. Technology based on these concepts meets four criteria, which are freedoms denied by the businesses of the free market: freedom to run software programs, freedom to study and modify code in which those programs are developed, freedom to distribute copies of a program and freedom to publish modified versions. The ability to rely on simple programs compensated for the lack of finances by enabling the reuse of available transmission equipment despite it being slow, old, and limited in processing capacity. Finally, it enabled them to be independent of multinational corporations to whom they would have paid licenses to access technological tools which include surveillance and store user data. Alongside the distribution of fanzines and CDs with installation packages of programs designed for the community radio model, the concept became spread among a diversity of actors fighting for social change: teachers of Local 22, the Popular Indigenous Council of Oaxaca “Ricardo Flores Magón” and the Indian Organizations for Human Rights in Oaxaca The Oaxacan Autonomous Solidarity House of Self-Sustaining (Autogestive) Work, a self-organized space in the capital of Oaxaca founded in 2007, which was a meeting place for various collectives and individuals with their own struggles and independent projects. During that year, people interested in various aspects of free media began to participate in the Latin American Free Software Installation Festival, the largest event for open-source software in Latin America, with the idea of spreading the use of free media in all areas exhibiting a growth in the presence of technology.8

Since then, both individual activists and established organizations have dedicated themselves to supporting the creation of educational and community radio stations within various indigenous communities. Often with transmitters engineered using only basic knowledge of electronics and manuals downloaded from the internet, autonomous servers were developed to be simple and replicable, so as not to depend on the government or infrastructure in the hands of private business as well as to safeguard the privacy of the content. The protests in Oaxaca caught the attention of activists outside the country who were involved with the organizing of community radio stations and sharing their knowledge of hardware and open-source software. Free Radio Berkeley in California sent forty radio transmitters through Project Tupa that were built for community use during collaborative training workshops in which activist Loreto Bravo participated, having returned to Oaxaca after experiencing repression during a stay in the United States.9 Bravo was one of the distributors of a distribution package of open-source software created especially for community radio stations called Etertics. Etertics was developed by Javier Obregón for the Argentine radio El Libertador and began to be spread through trusted networks throughout Latin America. Bravo was also part of Libera tu radio, a network of people linking social movements, community radio stations, and open-source software that helps to strengthen centers of production in Latin America that have moved toward open-source software or are in the process of doing so.10

The participation of international activists in the social uprising of 2006 helped to amplify the reach of radio broadcasts through the internet to audiences outside of the country, even as internet coverage remains sparse in most of the state [of Oaxaca]. In the past few years, initial experimentation has been done to develop decentralized networks of routers using the open-source operating system Libremesh as an alternative to conventional services offered by large telecommunication companies.

Community Radio Stations Live On!

According to Loreto Bravo, although there are challenges to overcome, the community radio model is a dynamic medium in constant evolution which has been adapted to the use of digital technology and the fusion of distinct means of content creation and diffusion (using social media networks or online streaming). Some of the difficulties faced by community radio stations arise from the fact that many communities may undergo days without electricity or be in places where the radio signal’s range is limited. The greatest problems, however, are the lack of basic financial resources, and the aggression suffered as a result of being a key tool in the effort to defend the land and speak out against human rights violations.11

While many radio stations maintain that they should not ask permission to exercise their right to freedom of expression, others, in order to protect themselves, go through the difficult formalities of acquiring a license established by reforms imposed by the Federal Telecommunication and Broadcasting Law in 2014, which opened up the possibility of certain concessions for public and social use.

This is the case of Radio Bëë Xhidza Aire Zapoteco, serving the citizens of Santa Maria Yaviche, in the mountains of Oaxaca City, which since its inception in 2006 has continued to function completely with open-source software.12

The majority of the indigenous communities mainly use radio broadcasting to communicate between one another through the sharing of knowledge, struggles, and other experiences of their lives for which there is no space in commercial channels of communication. During the pandemic, the community radio stations have functioned in places where official information has not reached to explain protective measures and social distancing, as well as share the health of members of the community and home remedies. The range, while local, varies between populations of 700 and 50,000 people, according to Loreto Bravo, but the large number helps to support projects rooted in autonomy and preserve self-sufficient ways of living originating before colonization. The movement of community radio stations, according to activists, is linked to and bolsters community efforts that the indigenous people of Oaxaca have developed since the 1960s to manage community resources.13 From this perspective, beginning with the community radio of Talea de Castro in the Sierra Juarez, the non-profit company Rhizomática emerged in 2009 to provide a service of installing community telecommunications infrastructure.14

If you liked this article, please consider subscribing or purchasing print or digital versions of our magazine. You can also support us by becoming a Patreon donor.

Notes

- Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos México, “Informe Especial sobre los Hechos Sucedidos en la Ciudad de Oaxaca del 2 de Junio de 2006 al 31 de Enero de 2007”: 4, 31 de Enero, 2007.

- Laura R. Valladares de la Cruz, “El asedio a las autonomías indígenas por el modelo minero extractivo en México”, Iztapalapa Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, año 39, no. 85 (julio 2018): 103-131.

- “Media Ownership Monitor Mexico”, última modificación 28 de Marzo, 2019, http://mexico.mom-rsf.org/es/.

- Jill Friedberg, Un poquito de tanta verdad, (United States-Mexico: Corugated Films, 2007), 92 min, https://vimeo.com/ondemand/unpoquitodetantaverdad.

- Hermann Bellinghausen, “Tras ser atacada, tomó la APPO 12 radiodifusoras en Oaxaca”, La Jornada, 22 de Agosto, 2006, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2006/08/22/index.php?section=sociedad&article=042n1soc.

- Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos México, “Informe Especial sobre los Hechos Sucedidos en la Ciudad de Oaxaca del 2 de Junio de 2006 al 31 de Enero de 2007”. 31 de Enero, 2007.

- International Amnesty, “Oaxaca, clamour for justice”, 31 de Julio, 2007, https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/AMR410312007ENGLISH.PDF; Ana Gabriela Rojas, “Caso Atenco: CorteIDH sentencia a México por violencia sexual, violación y tortura a 11 mujeres”, BBC News, 21 de Diciembre, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-46656044.

- “FLISOL”, https://flisol.info/.

- “Project TUPA”, https://radiotupa.org/index.html.

- “Libera tu radio”, https://liberaturadio.org/.

- Asociación Mundial de Radios Comunitarias, México, “Segundo informe sobre la situación de la radiodifusión comunitaria en México. Informe Julio 2012 a Junio 2014”: 24-27, 40-48.

- “Radio Bëë Xhidza Aire Zapoteco”, https://colectivoxhidza.org/radioairezapoteco/.

- José Gasca Zamora, “Gobernanza y gestión comunitaria de recursos naturales en la Sierra Norte de Oaxaca”, Región y Sociedad vol.26 no.60 (2014).

- “Rhizomática”, https://www.rhizomatica.org/