In Case of Darkness, or What to do With Incarcerated People

By Juan Moreno Haines

Volume 24, Number 1, Racial Capitalism

June 25, 2021

Lee este artículo en español aquí / Read this article in Spanish here.

“The Time is Always Ripe To Do Right.”

—Martin Luther King, Jr.

As an incarcerated person, I’ve had to relinquish all sense of control. Climate crisis, COVID-19, a healthcare plan . . . these are issues that I no longer have any agency over. The discussion and action regarding these issues might as well be occurring in another world. I am erased.

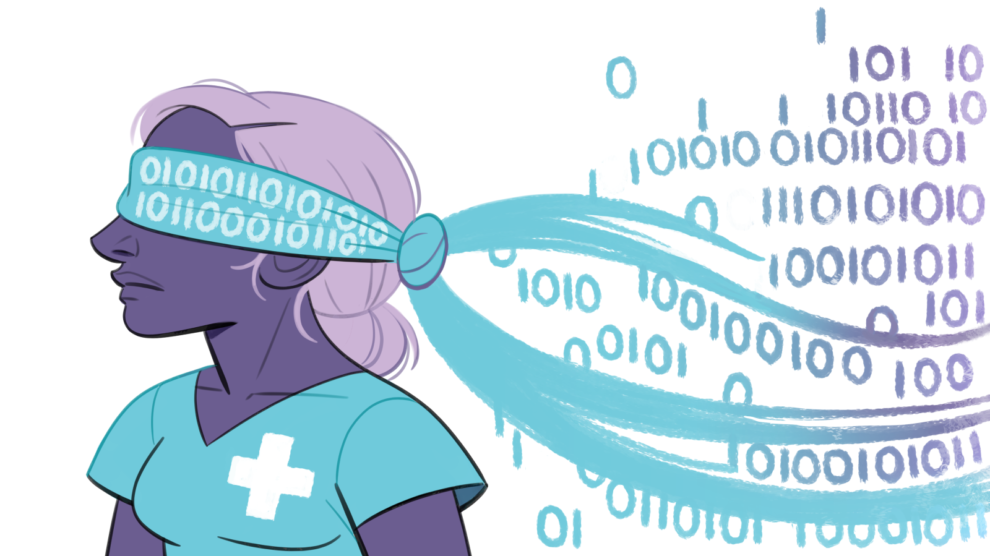

Social distancing, a mainstay practice to thwart the novel coronavirus, is impossible for me in the overcrowded San Quentin State Prison. The enclosed unventilated housing units make perfect environments for the virus to thrive as it continues to linger here after a bungled prisoner transfer in June of last year. To assess the San Quentin COVID-19 outbreak, public health experts from University of California, San Francisco walked through the prison and then, on June 16, published an Urgent Memo. In it, they identified specific actions for prison officials to take immediately in order to stave the outbreak and save lives. Prison officials essentially ignored the Urgent Memo and did what they thought feasible to address the crisis, and their disastrous actions resulted in more than three-quarters of the prison population becoming infected with the virus. Of them, twenty-eight have died as of February 2021, as well as a well-liked correctional sergeant. The California Court of Appeals blasted prison officials’ deadly failure, saying,

In the face of the pandemic, which appears to take its greatest toll among older individuals and in congregate living situations, and in an aged facility with all the ventilation, space and sanitation problems referenced in the Urgent Memo, [prison officials’] failure to immediately adopt and implement measured designed to eliminate double ceiling dormitory style housing and other measures to permit physical distancing between inmates is morally indefensible and constitutionally untenable.

Prison officials responded to the court’s criticism by ordering prisoners to be transferred from San Quentin, where two people are assigned to a cell about the size of a Walmart parking space, to other facilities that are pretty much under the same conditions as every California prison: at or near capacity, with enclosed/unventilated housing units where two people share tiny cells or live in dormitories. It was only after media attention that the San Quentin transfers were (temporarily) taken off the table. So, here I am in this prison where I spend more than twenty-three hours a day in a windowless cell. The mental toll is taxing.

So, here I am in this prison where I spend more than twenty-three hours a day in a windowless cell. The mental toll is taxing.

•

There’s a prison Urban Legend that says if the Big One hits, if there’s a nuclear attack, a foreign invasion or a major disaster, the plan is for the guards to lock us up and kill us before abandoning the prison grounds. The belief comes from the vaguely crafted “Emergency Operations Plan.” It officially reads, “Each warden must have in effect at all times an Emergency Operations Plan, approved by the Emergency Planning and Management Unit to assist in the preparation for response to and recovery from ‘all hazards.’ All hazards incidents are defined as any natural or man-made disasters or accidents that may significantly disrupt institutional operations or programs.” I’ve witnessed disasters in prison, some natural and some man-made. In California, it’s fires, in Texas and New York, it’s deadly heat. In Florida and Louisiana, storm surges and floods. During hurricane Katrina, several abandoned prisoners died from drowning. Several decades ago, power shortages in California caused by the energy corporation Enron were an example of a fully man-made disaster. Manipulative energy trading by Enron employees triggered an energy crisis that cost then governor Gray Davis his job. In the state’s prisons, it resulted in half-day scheduled power outages all summer long. I sat in my cell and listened to a battery-operated radio waiting for my cell door to open.

With the climate crisis taking place, increased fires and floods are causing emergencies inside prisons right now. All this makes me wonder: do people care about what happens to incarcerated people under these conditions? Is the urban legend true? How are prison officials going to react to the impending disasters when they come?

The answers to these questions make me dead living inside the Prison Industrial Complex, with its constant surveillance and control. It’s designed to incapacitate freewill and subdue individualization. It forces nearly everyone, including myself, into a peculiar state of docility. In 2018, I contacted the Marin County Health Department to find out the emergency plan for San Quentin. They advised me to contact the local sheriff’s department who referred me to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s Emergency Operations Plan. The uncertainty about what will happen to incarcerated people when a disaster comes demoralizes me.

•

My clock froze a little past 8 p.m. on a Saturday night. At the same time, the power strip for the TV clicked off and there went the 2019 World Series —along with the lights in my cell.

All electrical power to the prison had vanished. Everything went jet black. Silence enveloped the nearly 800 men-in-blue in San Quentin’s North Block who double up in 414 cells.

Earlier that day, the local news reported another PG&E fire prevention measure: electrical shut offs to selected counties in Northern California. The TV news map showed a red Marin County where San Quentin sits. I shrugged it off —this prison has its own emergency backup generators and during my stay, the backups foiled power interruptions several times before.

I sat cross-legged atop a bunk bed with snacks at my side and waited for the backups to kick in. I put my hand before my face and couldn’t see it. That was unsettling. My eyes adjusted to see the seven steel bars that make up my cell door. For our convenience the cell doors were unlocked, so I could have walked out to see what was happening. But I sat there and listened to the sounds of men-in-blue roaming around like investigative ants up and down the five tiers of North Block. I was calm in my third tier cell, not bothered by the commotion outside. Battery powered penlights (the kind that could be bought in prison packages) darted left and right of my cell door. White noises, indistinct rattles, and murmurs blended into the distant sound of showers running. The rumblings harmonized with laughter and jokes; somebody out there thought this was fun. The cacophony of voices and scuffling seemed to deepen the drama of sitting in the dark and waiting for something to happen. It was kind of like listening to the music score in a movie or the opening of a gangster rap.

Then, “Take it to your houses! Lock it up,” a green jump-suited correctional officer (CO) announced over a hand-held bullhorn.

On the tier, I could hear the sound of boots and keys jingling as a CO made his way up black painted steel stairs. He stopped at the end of the third tier, three cells from mine, and unlocked a padlock. He pushed an axe-handle like lever connected to a long metal shaft that runs along the top of 41 cells. Steel scraped against steel, then metal struck metal to trap me in a 4-foot by 10-foot box.

Michel Foucault lingered.

I remained cross-legged waiting for the generators to kick in, thinking about what prison does to men and women while under surveillance and control—how it affects the mind and body.

“Fuck the COs,” I heard someone say in the distance.

A short while later, I heard a CO state, “I’m not going no farther than this.” He refused to continue walking down the pitch-black tier.

Nearby, a man-in-blue was talking to someone I couldn’t see: “They all went outside,” the invisible man joked, referring to the departing COs. Were we being abandoned here?

My armpits began sweating and I felt short of breath. My head ached and my throat went dry. It was like the beginning stages of a virus. I widened my eyes, straining to see outside the steel bars as I was reliving a recurring nightmare.

I widened my eyes, straining to see outside the steel bars as I was reliving a recurring nightmare.

•

October of 1989 found me counting down seven more months to go on my first prison term. I sat cross-legged atop a bunk bed at Soledad State Prison. The cells have windows that open to fresh air. It’s a luxury to reach out to touch outside when your body is locked up.

It was just after 5 p.m. All prisoners were locked inside, waiting for Game 3 of the World Series to begin in San Francisco’s Candlestick Park.

“Count time,” a loudspeaker blared in the housing unit. It was part of a statewide headcount of every person in state prison—each one sends its tally to headquarters in Sacramento.

Then out of nowhere, the cinderblock building shook and wobbled. It jerked forward and backward. I grabbed the sides of my bunk. The lights slowly dimmed out. The TVs shut off. All electrical power was lost. Everything went quiet. The unnatural stillness smothered my thoughts. I looked out the window to see COs running across the yard.

My heart pounded with fear.

“They’re running away,” someone yelled.

I felt the cold dread of abandonment engulf my thoughts.

Mass panic ensued

Hands banged on khaki colored doors. Screams filled the hallowed housing unit, but began to quell as nightfall came. In due time, the backup generators kicked in and power was restored. Our TVs showed the damage and death in the Bay area. The fifteen second, 6.9 magnitude shake made 8,000 people homeless. Later the COs returned to give us box lunches of sandwiches and fruit for dinner—to satisfy our desire for care. Foucault got his wish as we became docile again.

•

On June 27, 2020 at 11:15 a.m., a CO came to my cell door and told me I tested positive for COVID-19. Then he locked me in and said everything would be brought to me. “Any questions?” I stood in silence, shaking my head as my mind drifted beyond the walls of prison and how this pandemic is killing people like me—elderly and Black. I wondered, why didn’t my cellie test positive? We’re double-upped in this tiny cage and North Block is filled to more than 180 percent of capacity. With no ventilation, dust, and filth floats around—grime is strewn on the fences and catwalks. My next door neighbor wears a mask that reads, “We’re All Gonna Die.”

I’ve already survived seasonal bouts with the flu, had norovirus twice, contracted a deadly staph infection, and even beat off Legionnaires Disease. Now, I’m in a place that’s gone from bad to worse after the bungled transfer. I’m trying to wrap my mind around another man-made disaster while at the mercy of bumbling prison officials who moved me, along with 62 other positive-tested COVID-19 prisoners from North Block to Badger Section—a reception center for newly arrived people to California’s Gulag. When I got to Badger, several reception prisoners were still there. One said he’s been there since December 23. He said he was tested for COVID-19 three times. The first two came back negative—the third positive—so they kept him in the dungeon-like place where the food is served cold. The second day we got showers. A few days later, we got telephone access. Some began yelling out their cells, asking for help. No one from mental health showed up. A CO walked the tiers spraying something I couldn’t smell. It took a month for electrical power to be installed for TVs, radios or for hot water. I felt stashed away with little hope to be seen by the rest of the world.

The outbreak in San Quentin shows that prison overcrowding should not be tolerated. It kills.

Someone called for a hunger strike to get hot meals, cleaning supplies, single-man cells, exercise, mental health services, and more phone calls. Race didn’t matter. Everyone stuck together, asking our caretakers to stop passing the buck. We kept hearing prison officials say they want to go back to the way we were, while ignoring the voices of those impacted by the systemic failures. It’s a struggle that strives for an impossible future as the age of COVID-19 has made us realize that we must work together no matter where we live. The global pandemic brought light to deep racial disparities, income inequalities, healthcare shortages, and a climate crisis that’s well underway. Meanwhile, the outbreak in San Quentin shows that prison overcrowding should not be tolerated. It kills. So, is there room to care about the darkness of prisons?

About the Author

Juan Moreno Haines is an award-winning incarcerated journalist and a member of the Society of Professional Journalists.