Racism and Repair: Science Under White Supremacy

By Ed Romano & Grace Huckins

Volume 23, number 3, Bio-Politics

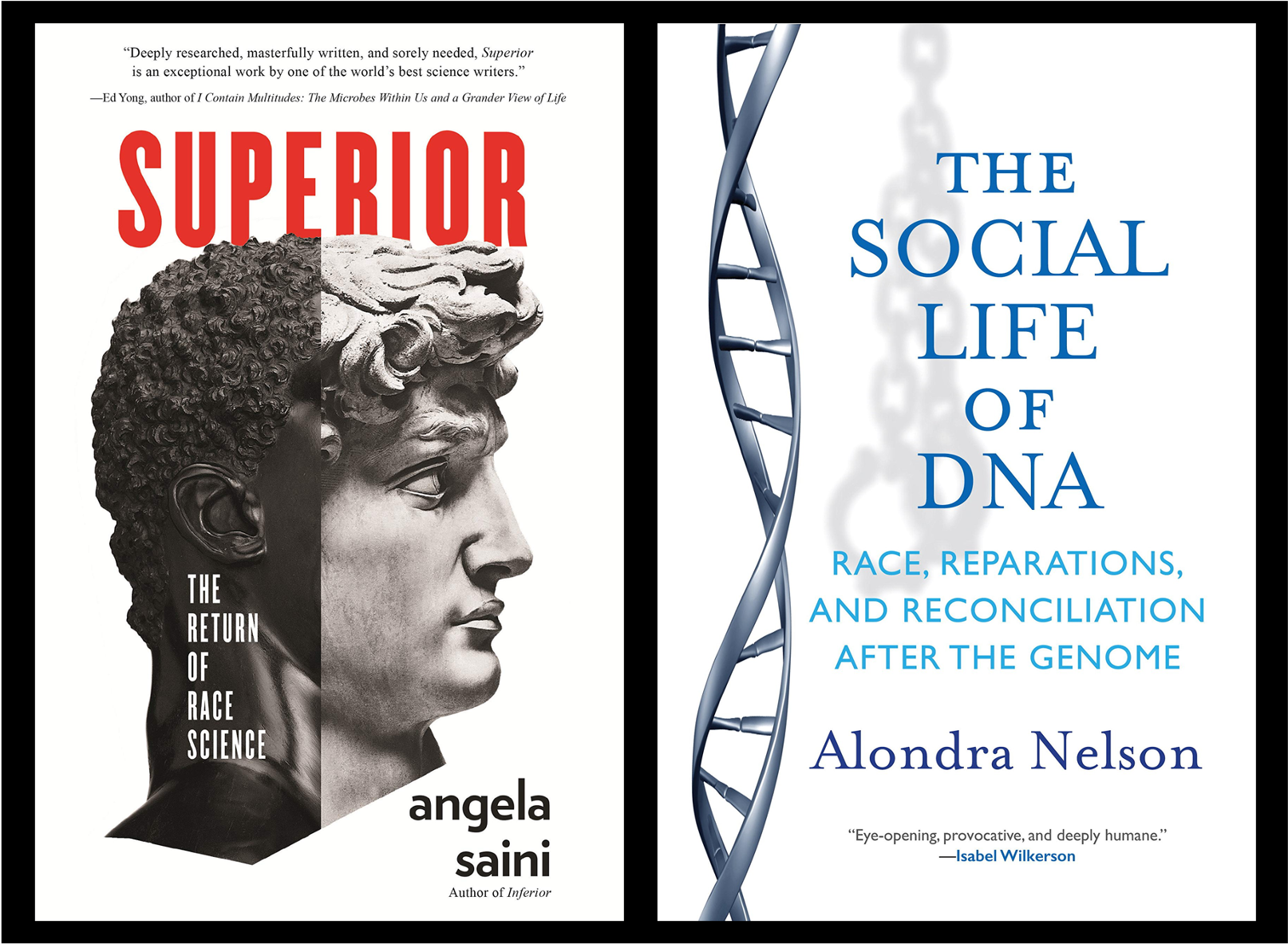

Superior: The Return of Race Science, by Angela Saini. Beacon Press (2019; 256 pages)

The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation After the Genome, by Alondra Nelson. Beacon Press (2016, 216 pages)

Over the past eight years, the role of race in public life has shifted with breakneck speed, from Obama’s re-election, to the uprising in Ferguson, to Trump’s election, to George Floyd’s murder and, finally, the nation-wide protests that followed. It is hardly surprising, then, that two recent books on race and science—Alondra Nelson’s The Social Life of DNA: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation After the Genome, published in 2016, and Angela Saini’s Superior: The Return of Race Science, published in 2019—should read so differently.

The Social Life of DNA reflects the era of purported color-blindedness under the first Black American president, although Nelson doesn’t linger in its illusions. In this context, she explores the ways in which genetic genealogy could function as an avenue for reconciliation projects to take hold amid a perceptibly dwindling consciousness for radical racial politics. She foregrounds the personal significance that root-tracing has for many of her subjects and emphasizes its social and political relevance. Her ethnographic approach allows her to open-mindedly examine the implications of science interacting with personal and racialized identities.

Nelson’s tone is a sharp contrast to the air of agitation that forms the backdrop of Angela Saini’s Superior. In Superior, Saini exposes the role that scientific racism has played not only in Trumpism but also in neoliberalism. When more and more individuals feel comfortable voicing their racial hatred in public, her argument—that current-day scientific racism is continuous with 19th and 20th century eugenics—rings discomfitingly true. Writing in light of the racial provocations of the current political moment, Saini deploys an urgent voice that makes clear the dire stakes of her subject.

Science’s impact is entirely contingent on the forces that wield it

Each book speaks to concerns about race and genetics, tinged with the particular anxieties of the political moments in which they were written, and together they highlight a timeless idea: though science’s long history of racism is baked into its tools, those tools can nevertheless be put to either liberatory or oppressive purposes. Saini shows her readers how easily science can be deployed to support racism and how often this still happens today. Nelson also grapples with scientific racism, but nevertheless offers glimpses of new technologies being used for justice. In both cases, science’s impact is entirely contingent on the forces that wield it.

Read Below:

1. Grace’s review of Superior

2. Ed’s response to Grace

3. Ed’s review of The Social Life of DNA

4. Grace’s response to Ed

Grace Huckins: Shades of Gray in Saini’s Superior

The election of Donald Trump brought new exposure to the old tradition of scientific racism. Peddled by commentators like Ben “facts don’t care about your feelings” Shapiro and others on the so-called “intellectual dark web,” this particular brand of bigotry relies on a sense of intellectual superiority and a belief that the academic mainstream has worked to cover up harsh truths about the differences among the races. It was in this context that journalist Angela Saini began writing Superior, which she calls “the book I have wanted to write since I was a child.” Her book could not have come at a better time: though it is unlikely that any member of the alt-right would pick up her book in the first place, much less be amenable to Saini’s argument, a confused and curious lay reader will learn from Superior just how dangerous scientific racism truly is.

The election of Donald Trump brought new exposure to the old tradition of scientific racism. Peddled by commentators like Ben “facts don’t care about your feelings” Shapiro and others on the so-called “intellectual dark web,” this particular brand of bigotry relies on a sense of intellectual superiority and a belief that the academic mainstream has worked to cover up harsh truths about the differences among the races. It was in this context that journalist Angela Saini began writing Superior, which she calls “the book I have wanted to write since I was a child.” Her book could not have come at a better time: though it is unlikely that any member of the alt-right would pick up her book in the first place, much less be amenable to Saini’s argument, a confused and curious lay reader will learn from Superior just how dangerous scientific racism truly is.

Saini’s prose is unfailingly clear, and she covers centuries of history without lapsing into unnecessary density or detail. She uses this scope to great effect, drawing throughlines from slavery and previous eras of eugenics to today’s prejudices. In light of their sordid pasts, ideas about racial IQ differences or health disparities no longer appear innocuous: Saini convincingly shows that they are, at their cores, racism in more palatable costumes. When pundits like Shapiro have achieved prodigious audiences, such a book can do a great deal of good.

But for readers who are familiar with this history, Superior has less to offer. Although Saini does explicitly acknowledge the complexity of scientific racism—the ways it can seep into ostensibly well-motivated projects, the valuable knowledge that racist minds do incidentally produce—she also often loses sight of these complexities. This tendency to view her subject through a black-and-white lens leads Saini to skirt some of the gnarlier questions that her topic introduces. When Saini covers Francis Galton, the so-called “father of eugenics,” she portrays him as Darwin’s kooky cousin, less talented and more racist than him in equal measure. But Galton was not nearly so one-dimensional: as he advocated for eugenics, he also made seminal advances in statistics, advances which he used in his bigoted quest to prove the superiority of Europeans. Any scientist who has ever calculated a standard deviation has used a tool invented by a man with immeasurable blood on his hands. Saini would have done far better to have forced her readers to confront this uncomfortable reality.

Saini also falters when she discusses the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP), an initiative that works to uncover prehistoric human migration patterns by sampling the genomes of isolated indigenous groups. Whereas the genome of, say, a New Yorker would be effectively useless as a tool for studying human migration—since that New Yorker, or their parents, or their parents’ parents probably came from quite far away—the genomes of individuals whose ancestors have lived on the same land for millennia may hold clues about when humans first reached that land. Saini quite reasonably takes issue with the project’s focus on genetic differences among populations, since scientific racism hinges on the idea that those differences are deeply important. Yet when she engages with the project, she fails to acknowledge the ways in which studying those differences could serve the legitimate goal of understanding human prehistory.

Moving science in the direction of justice will demand an unflagging commitment to wading into the messy middle ground where almost all science lives.

To avoid reinforcing ideas about the fundamental distinctness of racial groups, Saini suggests, the project should have sampled individuals more evenly across the globe, to capture the continuous genetic spectrum along which we all exist. But such data would tell us nothing new about human migration. The HGDP is surely a fraught project—human migration may be a valuable topic of study, but scientific racists could easily use its data to reinforce their own beliefs, and academics have long taken advantage of indigenous groups to further their own goals. Ultimately, deciding whether the HGDP and similar projects should proceed requires a careful weighting of its benefits and risks, all couched in the knowledge that the research is being conducted from within a fundamentally racist society. But Saini seems unwilling to explore this tension.

Saini does occasionally wade into this gray area, and her book is far better for it. Unfortunately, Superior gives the impression that difficult decisions are the exception as opposed to the rule, and that defeating scientific racism is mostly a matter of identifying and rejecting those projects and individuals that support racism. In reality, this essential task is incredibly difficult. Racism is baked into the pillars of the scientific endeavor, and no project can ever be deemed completely free of its influence. Much as defeating Trump can only ever be the beginning of a larger fight for justice, so too is delegitimating and de-platforming the obvious racists only the opening salvo in the battle against scientific racism. As long as science rests on the shoulders of racists, moving science in the direction of justice will demand constant vigilance and an unflagging commitment to wading into the messy middle ground where almost all science lives.

Ed’s response to Grace

This book, to me, was incredibly clarifying. As a person of color I felt connected to Saini when she revealed that this was the book she had wanted to write since she was a child. It contextualizes so much of the insidious worldview that has incubated science into its modern form, from the stubborn persistence of race in scientific language, to the dominating prescriptions of white supremacy that maintains its grip on science and other institutions like law, religion, and education, all the same.

Saini’s approach complements Alondra Nelson’s assertion about science being trans-scientific, inherently political by its very nature. To that end, I found Saini’s journalistic sleuthing to be a vindicating experience, as she chases after the perpetrators of scientific racism, from their historical inception down to their surviving footprints. Given this investigative scope, I didn’t expect her to give equal attention to the redemptions of science, as Nelson did in her book.

Within Saini’s excursions, I found an expert demonstration of exactly how racism gets baked into our scientific framework, persisting even without willful intent. She masterfully paints the process of how ideology becomes coded into a body of knowledge, which consequently renders those who blithely engage with it traffickers of miseducation and, to be blunt, racism.

Ed Romano: Science under the Possession of Political Power in Nelson’s The Social Life of DNA

In The Social Life of DNA, Alondra Nelson engages with genetic genealogy as a “participant observer,” illuminating the subculture of personal DNA enthusiasts who seek to reclaim their ancestry lost through the transatlantic slave trade. Nelson wrestles with what deciphering one’s own genetic history could mean for an individual who has been racialized by society, whose personal identity has been ravaged by the machinations of white supremacy.

In The Social Life of DNA, Alondra Nelson engages with genetic genealogy as a “participant observer,” illuminating the subculture of personal DNA enthusiasts who seek to reclaim their ancestry lost through the transatlantic slave trade. Nelson wrestles with what deciphering one’s own genetic history could mean for an individual who has been racialized by society, whose personal identity has been ravaged by the machinations of white supremacy.

Decades of field research and self-study leaves Nelson wondering if she could herself “deliver the emotion that this revelation was expected to elicit.” About to receive her DNA ancestry results, she expresses her ambivalence towards the technology’s revolutionary social potential. Her agnostic outlook is captured by DNA analysis’s divergent impacts in two of the book’s case studies: the New York African Burial Grounds project, which sought to discern the ancestral origins of over four hundred burial remains in lower Manhattan, and the fight for legal reparations for the horrors of slavery and centuries of unpaid labor. Ultimately, what drives these outcomes isn’t so much the technology itself, but those who are granted ownership over the power structure that subordinates it.

The first case study is described as triumphant, after the transfer of the project from the initial stewardship by Lehman College to that of the historically-black Howard University. The transfer was demanded by activists and the surrounding community, after the scandalously negligent excavation and storage of the skeletal remains came to public attention. A substantial amount of this influence came from Black people in positions of power, such as then NYC mayor David Dinkins. At Howard, the researchers conducted a battery of tests that included DNA analysis in order to find the specific African origins of the formerly enslaved. Their approach was in stark contrast to Lehman’s, where the researchers subjected the bones to ‘biological racing’, reminiscent of the eugenics-era practice of broad categorization by gross measures of cranial size and shape. As Nelson puts it, “the question undergirding the investigations carried out at the MFAT [Lehman] lab could be summarized as “‘Are these the bones of blacks?’”

Wary of the racialization being imposed upon the remains, the new project owners at Howard instead refined the research questions around “where in Africa did these bones originate?” effectively restoring the specific ethnic identities that expanded out in diaspora through DNA tracing. It’s under this change in research direction that DNA technology found a liberatory role, challenging the persisting notion of Blackness that has been forged into society by the violence of chattel slavery. And while technology is only as righteous as the decisions made by those who possess it, it’s through this new DNA analysis that we can see a glimmer of the ancestral histories destroyed by the Middle Passage.

The second case study recounts the fate of Farmer-Paellman v. FleetBoston (led by activist-attorney Deadria Farmer-Paellmann), a class-action lawsuit where the plaintiffs used DNA testing to stake a claim on reparations owed for the exploitation wreaked by the transatlantic slave trade. The class-action lawsuit sought to redistribute, to all Black Americans, ill-gotten wealth from companies like FleetBoston, who derived profits from slave labor by providing financing and insurance to slaveholders. The court dismissed the case based on the legal doctrine of “standing,” requiring a direct trace to the harmed (that is, the enslaved) be established. This requirement rested on an individual rights view, granting restitution only to proven direct descendents. Plagued by the wholesale erasure of familial relations endemic in chattel slavery, this presented an insurmountable challenge for most Black Americans. The prosecution attempted to bridge this information gap with DNA data, but due to the strict rule of standing, the court found such data tenuous. With a dogged commitment to find justice, the plaintiffs invoked the developing language of international law, with an appeal to human rights. They defiantly asserted that the DNA data spoke to matters beyond the allowances of US law, which codified slavery and prevents redress. They insisted that their newfound genetic lineages fleshed out what the transatlantic slave trade had stolen from all Black Americans: their identities. Looking to pave a legal pathway for winning reparations on a mass scale, they demanded amends commensurate with the harm done.

True transformation is kept out of reach, and these legal doctrines take the form of the master’s tools, unable to dismantle the master’s house.

In the end, the US court system ignored the “identity as a human right” claim. Given how domestic law instutionalized chattel slavery, it comes as no surprise that the will of the enslaved had no bearing on the laws designed to consign them. That same legal scaffolding survives to this day, excluding the will of those who would advocate for their due justice. As revealed by this case study, between the statute of limitations, sovereign immunity, and the doctrine of standing, the legal apparatus that condoned slavery has merely shifted into one that leaves its thefts, whether profit or identity, unreconciled. True transformation is kept out of reach, and these legal doctrines take the form of—as Audre Lorde might have put it—the master’s tools, unable to dismantle the master’s house.

Together, the two examples serve as lessons on the power intrinsic to ownership. The African Burial Grounds project demonstrated how a transfer of such ownership, even over just research questions, enabled a reclamation of lost histories. In contrast, Farmer-Paellmann v. FleetBoston exposes how a justice system once under the authority of the slave system, as it continues to exert its influence today, can just as easily deter progress or repair.

Grace’s Response to Ed

Nelson’s account of Farmer-Paellman v. FleetBoston in The Social Life of DNA is certainly her most dramatic example of the potential political power of genetic geneology, though currently there is no space in the US legal system for plaintiffs to claim slavery reparations based on the results of consumer DNA tests. But I don’t believe it is her most material example. Throughout The Social Life of DNA, Nelson follows a number of Black individuals who have found emotional fulfillment in their ancestry test results. Robbed by slavery of a sense of connection to their ancestral homelands, many of these individuals feel that DNA tests have allowed them to regain an inheritance that is rightfully theirs.

These tests are, of course, far from perfect—they can only trace direct matrilineal and patrilineal lines, among other shortcomings—and Nelson retains an attitude of skepticism toward their results. She also notes that people like Rick Kittles, CEO of African Ancestry, have a capitalist imperative to convince as many people as possible to take their tests. Simultaneously, Nelson emphasizes that these tests have real value to the people who choose to purchase them, even though their results may be limited. Nelson is far from wholeheartedly sanguine about the political potential of consumer DNA tests, but her depiction of their emotional benefits for descendents of the enslaved provides a necessary counterpoint to the dark picture that Saini paints in Superior.