January 3, 2023

On Killing Crocodiles

Colonial Zoology in Late Ottoman Palestine

By Elizabeth Bentley

An extended version of this article was originally published in Jerusalem Quarterly. This version was reproduced and edited with permission.

Clarence the crocodile drifts about lazily in the thick summer heat.1 It is a midsummer day at the Tisch Family Zoological Gardens in West Jerusalem. The zoo, known locally as Gan HaChayot HaTanachi or the “Biblical Zoo,” prides itself on its multiculturalism and “inclusivity” toward Palestinian visitors from occupied East Jerusalem.2 I linger in front of Clarence’s enclosure, glancing at the informational poster to my left. Visitors learn that while Clarence is not from Palestine, Nile crocodiles once lived in Palestine’s Mediterranean coastal marshlands. The poster narrates the Nile crocodile’s regional extinction in late Ottoman Palestine, beginning with a brief account of the last crocodile’s demise: “In 1905, the last crocodile was hunted in Israel by residents of [the Palestinian village] Jisar-A-Zarka.”3 “We must do everything,” the poster concludes, “so that the small amount of wildlife still found in our region will not meet the same fate as that of the Nile crocodile.”4

The Biblical Zoo’s extinction narrative reflects Israel’s settler-colonial self-fashioning as the land’s rightful environmental stewards and saviors. The narrative hinges on the last crocodile’s symbolic singularity; the demise of the last living member of a species marks extinction through “a singular body and a singular moment.” Along with perpetuating Israeli stereotypes of Palestinians as ecologically irresponsible,5 the Biblical Zoo’s story obscures colonial zoologists’ historic role in perpetuating Palestinian crocodile extinction. It is this violent history—and its enduring impact—to which I now turn.

The Palestinian Crocodile

Scientists generally presume that the crocodilian species in Palestine was the “true” Nile crocodile, Crocodylus niloticus.6 Nile crocodiles are among the most notorious of all crocodilians due to their large size, aggressiveness, and tendency to eat humans. They are indigenous to the African continent, including, but not exclusively the Nile River that appears in their Latin taxon name.7 Nile crocodiles had a relatively small habitat in Palestine, which was the northernmost terrain where this species was found in the wild.8

From a zoogeographical perspective, the presence of Palestinian crocodiles and their small habitat is fairly unsurprising.9 Due to its location in the Great Rift Valley and at the juncture of three continents, historic Palestine is exceptionally biodiverse. It contains two primary climatic regimes and approximately twenty-three distinct ecosystems.10 Nonetheless, both before and after their regional extinction the crocodiles have consistently been treated as an ecological anomaly.

In numerous lively origin stories, Palestine’s crocodiles are framed as an introduced species that was transported to the Mediterranean coast as property from Egypt by one of several waves of human conquerors: Greek, Roman, or Egyptian.11 Most of these origin stories, which primarily circulated orally and have only sporadically been documented in writing, relate to the ruins of prior civilizations and corresponding place names that remain embedded in the coastal landscape.

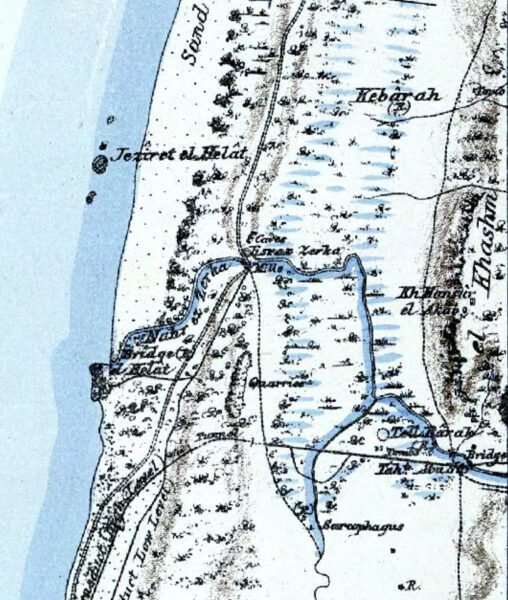

Habitat

In the late nineteenth century, the crocodile was one of a multitude of species that inhabited and drew sustenance from the Zor al-Zarqa/Kabbara marshlands.12 Naming these historic multispecies relations is crucial in order to understand the impact of the crocodile’s extinction. As apex predators, the crocodiles’ formidable appetite helped regulate the marsh ecosystem. They feasted on crustaceans, frogs, fish, migrating birds, and livestock that came to drink from the Zarqa river.13 Crocodiles were also a food source for other species. In one of the most iconic of symbiotic interspecies relationships, spur-winged plovers would have daintily picked leftover meaty tidbits from the crocodiles’ open mouths, cleaning the crocodiles’ teeth in the process.14 Crocodile eggs and hatchlings were eaten by otters.15 Mosquitoes—which thrived in the still waters—sucked blood from crocodiles and from all the other living, blood-filled beings that moved through the marshes.

The marshlands were also a source of economic and cultural value for Palestine’s human population. The freshwater Nahr al-Zarqa, known for its clear blue waters, was used for drinking and agriculture.16 Marsh water powered a flour mill that operated at the edge of a Roman-era stone dam in the marsh.17 The marshlands were near Caesarea and multiple Palestinian villages. Beginning in 1882, they were also adjacent to one of the earliest Zionist settlements, Zikron Yaakov. The marshlands themselves were home to two communities of Bedouin origin, ‘Arab Kabbara and ‘Arab al-Ghawarna, who lived in tent encampments and caves in the marshland’s rocky hills.18

‘Arab al-Ghawarna roughly translates to “people of the lowlands” or “marshes.” For reasons of social status intertwined with their marshland dwelling-place, the name carries a fraught and at times stigmatized history.19 The Ghawarna who lived in the Zor al-Zarqa/Kabbara marshlands were primarily members of the ‘Ammash and Jurban families.20 Palestinians of Sudanese descent were also affiliated with the Ghawarna during this period. The marshes have been described as a quasi-Maroon community that welcomed individuals who were marginalized elsewhere or fleeing violence.21 Their blackness—and the “darkness” of the Ghawarna more generally—was the subject of repeated, disproportionate fascination in the writings of colonial researchers who came to hunt crocodiles and document marshland flora and fauna.

Colonial Zoology in Palestine

Colonial zoologists and collectors saw and appreciated Palestine’s bountiful plants and animals as objects of scientific inquiry. This scientific appreciation was inextricable from imperialist ambitions and the drive for profit. There were no wildlife protection laws in Palestine until 1924, which was after crocodiles’ likely regional extinction, and even then, the laws were loosely enforced.22 Colonial zoologists not only observed and wrote about Palestinian animals in their natural habitat. These zoological work were one of extraction and commodification.23 Euphemistically termed processes of “collection” involved a network of human and nonhuman actors, whereby colonial zoologists hunted and killed Palestinian animals, studied them, and transported their remains overseas. Disemboweled, stuffed with wire and flax, and then displayed in glass cases, Palestinian animals were reanimated as spectacles for the viewing pleasure of museumgoers in London and Berlin.

While aligned with the broader trends in colonial zoology, the allure of the last Palestinian crocodile surpassed the confines of scientific inquiry; it adapted a symbolic, even mythical quality. Colonial zoologists’ ongoing speculation about Palestinian crocodile extinction necessitated a degree of willful (or internalized) unknowing about Palestine and Palestinians. Colonial zoologists were heavily dependent on Palestinians’ ecological expertise. Despite this, their writings convey mistrust and condescension toward Palestinians, along with a detachment from how local populations lived alongside Palestinian ecology.24 Colonial scientific literature on Palestinian animals frequently perpetuated the racist, historically inaccurate outlook of “science for the West, myth for the rest.”25 Yet colonialist writings on the last Palestinian crocodile reflected their own symbolic attachments and investment in mythical thinking.

Lastness

Colonial zoologists’ fixation on the last Palestinian crocodile was partially driven by an enduring European fascination with “lastness” as a spatial-temporal construct. This fascination exemplifies the convergence of evolutionary science and imperial sensibilities that shaped colonial research on Palestinian life and land. During this period, evolutionary theory was “understood as the preeminent doctrine of empire” by both its proponents and critics.26 In colonial cultural production, it converged with the myth of the “last of the race” and an enduring fascination with the “rise and fall” of civilizations.27 From a strictly Darwinian standpoint, rarity is associated with weakness rather than value.28 Certainly, colonialists’ writings on Palestine reflect their confidence in their superiority and commitment to white European supremacy. Yet these sentiments, and their violent and exploitative activities, were often cloaked in an air of “imperialist nostalgia.”29 As the Palestinian historian Beshara Doumani observes, these skewed, orientalist studies aimed at “documenting an unchanging society before its anticipated extinction due to contact with the West.”30 They failed to see and address Palestinian society’s cultural, economic, and intellectual heterogeneity and dynamism.

Place

The crocodiles were associated by name with several archeological and geographic sites near their habitat which were connected to Hellenistic and medieval Crusader histories in Palestine. These sites included the ruins of the Greco-Roman port city Crocodilopolis and the nearby river Nahr al- Zarqa, which during the Greco-Roman period was allegedly known as Crocodeilon. The ruins and river attracted a broad spectrum of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Europeans, many of whom were apt to speculate about the significance of these active and lapsed place names. This speculation directed attention back to the area’s live crocodile population, and so references to Palestinian crocodiles were ubiquitous in writing by European researchers and travelers who might not otherwise have cared about Palestinian wildlife.

Through their excavation and representation of Palestinian crocodiles’ place-based historical associations, colonialists perpetuated a Eurocentric interpretation of Palestine’s material history.31 The crocodile served as a reptilian conduit for rewriting (and claiming ownership over) Palestine’s past, thereby de-Arabizing the history of the coastal marshlands.32 The more scholarly, research-based colonial literatures often included uneven literary historiographies of references to local geography and the crocodiles; these jumped from Greco-Roman to medieval Crusader to nineteenth-century European-authored texts, omitting or glossing over periods in Palestine’s history characterized by Arab rule.33 As such, the Palestinian crocodile’s origin story aligned with the grand origin story of so-called Western civilization. Through the act of observing (if not successfully hunting) Palestinian crocodiles, nineteenth- and twentieth-century colonialists attempted to weave themselves into the noble legacy of conquerors past.

Scarcity

The last crocodile’s scientific value was inextricable from its market value as a scarce commodity. Alongside taxonomy and habitat, colonial zoologists’ writings on last Palestinian crocodiles were interspersed with references to money: an inability to afford purchasing a last crocodile,34 a willingness to pay “any price within reason,”35 and a triumphant proclamation that “the promise of a reward produced”36 a specimen after a zoologist’s unsuccessful hunt.

Like extinction science, neither capitalist conceptions of property nor the commodification of animal byproducts was solely Europe’s domain during this period.37 However, in colonialists’ writing on Palestinian crocodiles, capitalist value relations figured as a near-taxonomic distinction between “us” and “them,” colonizer and colonized.

Exploitative economic dynamics are most striking in colonial zoologists’ representations of the Ghawarna. Colonialists were quite forthcoming about their reliance upon the Ghawarna for labor, hunting prowess, and knowledge of marshlands ecology. Nonetheless, they never once mentioned paying or otherwise compensating members of the Ghawarna community. And despite colonial zoologists’ keen appreciation of the Palestinian crocodiles’ market value, there was no consideration of either the crocodiles or marshlands as the Ghawarna’s property—at least not in these terms.

End of Colonial Speculation

Colonial zoologists’ half-century of speculation about the whereabouts of the last Palestinian crocodile—and by extension, Palestinian crocodiles’ extinction status—ended definitively with the 1924 Zor al-Zarqa/Kabbara marshlands drainage project. Colonial zoologists recognized that by destroying the crocodiles’ former habitat, marsh drainage made crocodile life in Palestine impossible.

The drainage project reflected shifting power dynamics in British Mandate Palestine. Initiated by the British Mandate and Palestine Jewish Colonization Association (PJCA) in the early 1920s, it was fueled by a different configuration of “state, science, and capital” than the colonial zoological project. The drainage project was also a vehicle for settler-colonial land appropriation. PJCA was eager to take over the so-called “waste land,” which was near several existing Zionist settlements. The Ghawarna’s efforts to defend their land in a protracted legal battle were unsuccessful. Their labor was exploited during the drainage and they were resettled in the newly established city of Jisr al-Zarqa, which was created on a fraction of their former land.

Extinction Otherwise

In our conversations about Jisr al-Zarqa’s interwoven environmental and human histories, local historians and community figures Sami al-Ali and Mohamad Hamdan shared their theory—cultivated through years of archival research and conversations with community elders—that their community’s Nakba, or catastrophe, dates to the 1924 drainage project.38 The violent and disorienting transition to urban living, coupled with the near-total destruction and loss of their land, disrupted ways of life and livelihood that were intertwined with the marshland ecology.39

Al-Ali and Hamdan’s research foregrounds how ecological devastation—specifically habitat destruction and biodiversity loss—have detrimentally impacted indigenous Palestinian ways of life. By extension, al-Ali and Hamdan’s community-based research opens analytical pathways for recognizing, even mourning, the loss of nonhuman animal life in Palestine without valuing it over indigenous human life.

By foregrounding the interconnectedness between human and nonhuman flourishing in their ancestral wetlands, al-Ali and Hamdan’s research paves the way for a relational approach to extinction that does not bifurcate Palestine’s nature from its human culture.40 Instead of a myopic focus on a single species, a relational approach to extinction considers the interspecies ways of life that unravel as species go extinct.41 Rather than fixating on the death of a singular specimen, it addresses the intersecting circumstances that contribute to an extinction as it unfolds over time. And crucially, this approach foregrounds the experiences of those whose daily lives are most impacted and left most vulnerable in an extinction’s wake.

—

Elizabeth Bentley is an American Council of Learned Societies postdoctoral fellow at New York University. She is at work on her first book project, The Last Crocodile in Palestine: Envisioning Extinction in the Ruins of Empire. Research for this article was conducted with the support of the American Association of University Women and the Bilinski Education Foundation. Along with SftP editors Nadine Fattaleh and Calvin Wu, Elizabeth extends a special thanks to Sami al-Ali, Saidah al-Ali, and Mohamad Hamdan for being generous with their time and for allowing her to share their insights in this article.

Ram Sallam is a Palestinian artist and sculptor, currently dislocated in Algeria.

Notes

- Clarence’s origin story is described on an adjacent plaque. I analyze it and the Biblical Zoo at greater length in my book manuscript in progress, The Last Crocodile in Palestine: Envisioning Extinction in the Ruins of Empire.

- “Chazon v’ Matarot,” Gan HaChayot HaTanachi, https://biblical-zoo.webflow.io/heb/goals, accessed December 9, 2019; see also Irus Braverman, “Animal Frontiers: A Tale of Three Zoos in Israel/Palestine,” Cultural Critique 85 (Fall 2013): 122–62.

- Neither Israel nor Jisr al-Zarqa existed at the time. I return to this point in the concluding section, but see Geremy Forman and Alexandre Kedar, “Colonialism, Colonization, and Land Law in Mandate Palestine: The Zor al-Zarqa and Barrat Qisarya Land Disputes in Historical Perspective,” Theoretical Inquiries in Law 4, no. 2 (2003): 1–21.

- Wall plaque, Nile Crocodile Exhibit, Tisch Family Zoological Gardens, Jerusalem.

- See Jumana Manna, “Where Nature Ends and Settlement Begins,” e-flux 113 (November 2020), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/113/360006/where-nature-ends-and-settlements-begin/. On the “weaponization” of Palestinian landscapes, see Saad Amira “The slow violence of Israeli settler-colonialism and the political ecology of ethnic cleansing in the West Bank,” Settler Colonial Studies, November 28, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2021.2007747.

- Evon Hekkala et al., “An Ancient Icon Reveals New Mysteries: Mummy DNA Resurrects a Cryptic Species within the Nile Crocodile,” Molecular Ecology 20, no. 20 (2011): 199–215.

- S. Isberg et al., “Crocodylus niloticus,” IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019, http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T45433088A3010181.en.

- Isberg et al., “Crocodylus niloticus.”

- I refer to the crocodiles as “Palestinian” to clarify the geographic range of the Nile crocodile’s regional extinction for the purposes of this study—that is, from their habitat in historic Palestine. The colonial zoological literature composed during the late Ottoman and British Mandate periods often refer to the crocodiles as Palestinian even though “Palestinian crocodiles” was not (and never has been) a scientifically recognized species classification.

- Rotem Dotan and Weil Gilad, “Natural Ecosystem-Units in Israel and the Palestinian Authority: Representativeness in Protected Areas and Suggested Solutions for Biodiversity Conservation,” Journal of Landscape Ecology 7, no. 1 (2014): 91.

- See, for example, Yehudit Ayalon, Tanninim v’Nachal Tanninim [Crocodiles and Crocodile River] (Jerusalem: HaYechida L’Yediat HaAretz v’Limudei HaSadeh, Misrad HaHinuch v’Tarbut, 1979), 3–4. I write about these stories in my book manuscript in progress, The Last Crocodile in Palestine: Envisioning Extinction in the Ruins of Empire.

- Alon Tal and David Katz, “Rehabilitating Israel’s Streams and Rivers,” International Journal of River Basin Management 10, no. 4 (2012): 318.

- For crocodile appetites, see Gordon Grigg and David Kirshner, Biology and Evolution of Crocodylians (Victoria: CSIRO Publishing, 2015), 266–77.

- Signpost, “Spur-winged Plover,” Nachal Tanninim Nature Reserve, Beit Hanania, Israel.

- E. Graf Von Mülinen, “Beiträge zur Kenntnis des Karmels,” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 30, no. 3–4 (1907): 139.

- Author interview, Sami al-Ali, 2 January 2020.

- John Peter Oleson, “A Roman Water Mill on the Crocodilion River near Caesarea,” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 100 (1984): 137–52.

- Forman and Kedar, “Colonialism.”

- See also Sliman Khawalde and Dan Rabinowitz, “Race from the Bottom of the Tribe that Never Was: Segmentary Narratives amongst the Ghawarna of Galilee,” Journal of Anthropological Research 58, no. 2 (2002): 225–43.

- Author interview with Mohamad Hamdan, 5 January 2020.

- Author interview with Hamdan, 5 January 2020; author interview with Saidah al-Ali, 2 January 2020.

- Tal, Pollution, 46–47; “Hunting Ordinance (passed in 1924),” Laws of Palestine: Including the Orders in Council, Ordinances, Regulations, Rules of Court, Public Notices, Proclamations, etc. (1932– [33]).

- My approach to “extraction” is informed by Macarena Gomez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

- Nadia Abu El-Haj, Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-fashioning in Israeli Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 32.

- Colin Scott, “Science for the West, Myth for the Rest? The Case of James Bay Cree Knowledge Construction,” in The Postcolonial Science and Technology Studies Reader, ed. Sandra Harding (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 175–97. See also Marwa Elshakry, “When Science Became Western: Historiographical Reflections,” Isis 101, no. 1 (2010): 98–109.

- Marwa Elshakry, Reading Darwin in Arabic, 1860–1950 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 10.

- Fiona J. Stafford, The Last of the Race: The Growth of a Myth from Milton to Darwin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994); Elshakry, Reading Darwin, 10.

- Stafford, Last of the Race, 291.

- Renato Rosaldo, “Imperialist Nostalgia,” Representations 26 (1989): 107–22.

- Beshara B. Doumani, “Rediscovering Ottoman Palestine: Writing Palestinians into History,” Journal of Palestine Studies 21, no. 2 (1992): 9.

- Abu El-Haj, Facts on the Ground, 13–14.

- On de-Arabization, see Nur Masalha, The Palestine Nakba: Decolonising History, Narrating the Subaltern, Reclaiming Memory (London: Zed Books: 2012), 10.

- Doumani, “Rediscovering Ottoman Palestine.” Journal of Palestine Studies 21, no. 2 (1992): 5–28.

- Ernst Schmitz, “Crocodiles in Israel,” Holy Land (1921): 117–19, reprinted in Leshem, Goren, and Amit, HaAv Ernest Schmitz, 93– 95.

- “Advertisements,” Palestine News: The Weekly Newspaper of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force of the British Army in Occupied Enemy Territory 1, no. 6 (11 April 1918); 10.

- Tristram, Flora, 155.

- Doumani, “Rediscovering Palestine”; Seikaly, Men of Capital.

- Author interview with Sami al-Ali; author interview with Hamdan. Al-Ali and Hamdan’s community-based research reflects Sherene Seikaly’s powerful theorization of the Palestinian archive as a project that “resists settler-colonialism’s imperative to isolate, to separate and to erase.” Sherene Seikaly, “Gaza as Archive,” in Gaza as Metaphor, ed. Helga Tawil-Souri and Dina Matar (London: Hurst, 2016), 231.

- Author interview with Sami al-Ali.

- See also Penny Johnson, Companions in Conflict: Animals in Occupied Palestine (Melville House Printing: 2019), xvii.

- Deborah Bird Rose, Thom van Dooren, and Matthew Chrulew, “Introduction,” in Extinction Studies: Stories of Time, Death and Generations, ed. Deborah Bird Rose, Thom van Dooren, and Matthew Chrulew (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 4.