Richard Lewontin: Race Science for the People

By Joseph L. Graves Jr.

Lewontin Memorial Collection

August 8, 2021

“The apparent homogeneity within races as compared to the ‘obvious’ difference between them stems partly from the fact that our consciousness of racial differences is constantly being reinforced socially because racial distinctions serve economic and political ends.”

—Richard Lewontin, The Genetic Basis of Evolutionary Change, 1974. Pg. 152.

Racism created race.1 This statement refers to the social definition of race, or race as it has been lived in Western society, beginning with the age of European discovery. Social definitions of race are historically and culturally contextual. They combine elements of morphological, cultural, linguistic, and religious differences in the service of social dominance hierarchies.2 Indeed, as Lewontin pointed out above, these racial schemes only exist to serve political and economic ends. The biological race concept, however, has a different history.

Conceived in a creationist framework, the biological race concept shifted following the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859 from a religious to an evolutionary foundation.3 The biological race concept had its origins in classification. The criteria for biological races have changed through time. At first they were based on morphology, followed by geographical zones, and finally gene frequencies. Specifically, developments in the understanding of intraspecific variation influenced social conceptions of race (and vice versa). We can now say with great confidence that our species, anatomically modern humans, does not have biological races. We know this in large part due to the contributions of Richard C. Lewontin.

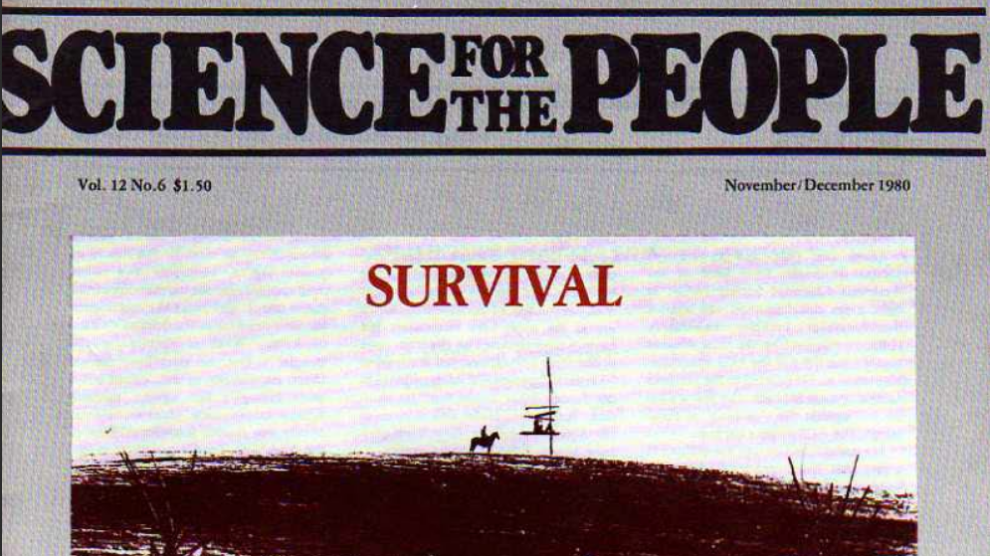

I first met Richard Lewontin in 1978, when I was a graduate student searching for a potential PhD mentor. My conversation with him involved research I was engaged in concerning the distribution of vectors of schistosomiasis in Africa. We never discussed his thoughts on “race.” Despite my having been awarded an NSF graduate research fellowship, Harvard University found a reason not to admit me (citing the inability of finding me a suitable graduate mentor). For this reason I ended up beginning my PhD at the University of Michigan in 1979.4 It was there that I became a part of Science for the People and was exposed to Lewontin’s seminal work on within-species genetic variation and its relationship to the biological race concept.

Creationist ideas concerning variation within species go back to Aristotle (384–322 BCE). Despite his essentialist ideology, Aristotle did discuss variation within species in De Partibus (Parts of Animals, written around 350 BCE). Aristotelian thinking dominated biological thinking until the nineteenth century. Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (first published in 1735) recognized the existence of varieties within animals and plants.5 He thought that varieties could be caused by different aspects of the environment, such as climate or altitude. He did not name human varieties (or races) until the tenth edition published in 1758.6 In the eighteenth century, European creationists saw human varieties as belonging to one species (monogenism), yet some were characterized by various states of degeneration from the fall of Adam (Europeans least degraded, and Africans most degraded). This changed in the nineteenth century, when the idea that there were multiple human species (polygenism) dominated naturalist thought, supported by the Pre-Adamite race theory and the “Zones of Creation” ideas of Louis Agassiz.7

We can now say with great confidence that our species, anatomically modern humans, does not have biological races. We know this in large part due to the contributions of Richard C. Lewontin.

Although Darwin chose not to discuss humans in On the Origin of Species, its implications for both common descent and human evolution were clear. However, soon after Origin’s publication, ideas about human evolution began to appear. Most of these represented Africans as the primitive progenitors from which the higher races evolved.8 In 1871, Darwin would take on the question of human evolution (polygenism and race) in The Descent of Man. Darwin concluded that there was one human species and that its “races” represented “protean or polymorphic” forms within it.9 Darwin did not question the meaning of the term “race” within this work; this was in part because Darwin did not have the tools to comprehend the origin or maintenance of polymorphism, i.e. heredity. This required the theoretical developments of the Neo-Darwinian synthesis of the early twentieth century.

It is highly likely that Lewontin’s initial theoretical exposure to the biological problem of race resulted from his training with Theodosius Dobzhansky at Columbia (1952–1954). Ashley Montagu (and his students) had already laid out the core problem with attempting to classify human groups as biological races in 1942.10 This problem was further elaborated by Theodosius Dobzhansky and Leslie Dunn (Columbia) in their work Heredity, Race, and Society, published in 1946.11 In addition, the Second World War resulted in a graphic exposure of the logical consequences of racial and eugenic theories. This contributed to the decision of the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to call together a panel of scholars to tackle the concept of race in 1949, which resulted in the publication of two statements on race (1950, 1951).12

The 1950 statement dismissed the concept of race as altogether socially constructed. However, this statement was crafted by a committee comprised predominantly of social scientists (only Montagu and Juan Comas of Mexico were physical anthropologists). The 1951 committee placed more emphasis on the existence of meaningful genetic differences between human races. The second statement, entitled “Statement on the Nature of Race and Race Differences,” was drafted by a committee that included five geneticists and seven physical anthropologists, including Julian Huxley, Gunnar Dahlberg, Leslie Dunn, J. B. S. Haldane, Ashley Montagu, and Theodosius Dobzhansky.

The disagreement over the nature of the genetic differences between human races resulted in part because, up to this point in history, these supposed differences had not been accurately measured (nor had genetic variation within any species). In 1951, Dobzhansky discussed race formation. His definition of a biological race was: “Genetically distinct allopatric populations of a species are termed geographic races, subspecies, local varieties, or simply races.”13 The problem with this definition is determining what amount of differentiation constitutes “genetic distinctness.” He further described races as Mendelian populations that differ in frequencies of one or more genetic variants, gene alleles, or chromosomal structures. Several examples of this are given in the chapter, including the frequency of chromosomal inversions in the fruit fly Drosophila pseudoobscura, coat color in hamsters, color pattern of the beetle Harmonia axyridis, flower color Linanthus parryae, and humans. Of course if one utilized this definition, then there could be any number of geographically based races within the human species that would not match the socially defined ones produced by historical racism. For example, one could describe high- and low-altitude adapted, or lactose persistence “races.” Both of these categories would contain populations that did not correspond to the socially defined races.

The Second World War resulted in a graphic exposure of the logical consequences of racial and eugenic theories.

Dobzhansky also made the point that races are not static entities but are the result of a process. It is precisely with regards to these amorphous definitions that the work of Richard Lewontin was revolutionary. Lewontin was interested in the question of how much genetic variation should exist within a species. The classic model of Ronald A. Fisher predicted that natural selection should eliminate lower fitness genetic variants.14 Therefore, if the Fisher model was true, there should be little polymorphism in nature. In contrast was the balance theory of polymorphism, which held that heterozygote superiority would retain a great deal of standing genetic variation within populations. A consequence of the balance theory was that polymorphism should be abundant within natural populations.15 Lewontin had been studying the amount of polymorphism in natural populations since at least 1960. This was made possible by the development of protein gel electrophoresis to differentiate slight differences in protein structure that resulted from allelic substitutions. In 1970, this method was used to examine allelic differences between Europeans and Black Africans. This study found that of twenty-seven loci, twenty were monomorphic in both groups, that six of the loci had very close allelic frequencies, and only one, the PGM-3 showed a strong differentiation between the groups.16

In 1972, Lewontin examined this problem in greater detail in “The Apportionment of Human Diversity.”17 This paper showed that the amount of genetic variation within purported human races was much, much greater than the amount of variation between them. To accomplish this, he used data on allelic variation in several human populations that had been in the past viewed as comprising biological races (Caucasians, Black Africans, Mongoloids, South Asian Aborigines, Amerinds, Oceanians, and Australian Aborigines; see Table 2 of his paper). He then examined the range of variation at seventeen genetic loci (e.g. regions coding for haptoglobin, Hp; 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 6PGD; ABO blood group; rh factor) within and between purported races. Using a standard diversity information index (Shannon’s H), he then calculated variation within populations (Hpop/Hspecies), between populations within races ([Hrace – Hpop]/Hspecies), and between races ([Hspecies-Hrace]/Hspecies). Despite his limited data set, Lewontin’s calculations showed that more than eighty-four percent of the genetic variation in our species occurred within populations, compared to less than fifteen percent of the genetic variation occurring between so-called races. This was salient proof that our species did not have biological races. Remember that Dobzhansky’s argument for the existence of biological races required that there be genetic “distinctness” between such entities. Lewontin’s measurements demonstrated that no such distinctness existed. In addition, he wasn’t the only person to report this result. In the same year, Arun Roychoudhury and Matatoshi Nei came to the same conclusion.18

Racists and racialists were quick to attack this conclusion. If Lewontin’s result was true, it threatened to break down the very edifice on which scientific racism stood. The founding principle of scientific racism is the idea that there are reliable and causal genetic differences between human races. Several of the assaults against Lewontin’s science were motivated and rationalized by his Marxist critique of science and society.19 However, it was much harder to dismiss Roychoudhury and Nei, as well as the avalanche of papers that followed using other forms of genetic markers (restriction fragment length polymorphisms, DNA sequencing) reaching the same conclusions.

In 1978, Sewall Wright published a monumental tome covering his thinking in evolutionary genetics. Volume four concerned itself with variability within and among natural populations.20 In his chapter entitled “Racial Differentiation in Mankind,” it is notable that he still used the term race to describe the “major divisions” of mankind (negroids, caucasoids, and mongoloids), even while citing Nei and Roychoudhury (but not Lewontin) concerning the greater genetic variability within these groups than between them. Even more amazing was how throughout the chapter he adhered to the notion of major racial distinction, while he presented all the arguments for why such distinctions were not real!

If Lewontin’s result was true, it threatened to break down the very edifice on which scientific racism stood.

In 2006, I found myself joining a group of scholars defending the nonexistence of biological races within our species. The assault on this fact was organized around Lewontin’s methods.21 It began with a publication by A. W. F. Edwards (a student of the eugenicist, R. A. Fisher) in 2003. This was followed by an op-ed piece in The New York Times by Dr. Armand Leroi on March 14, 2005.22 In this piece, Leroi argued that the concept of “race as a social construct” was unraveling due to new results examining the genetic diversity of human populations. He hitched much of his argument on the deliberations discussed in a scientific conference I actually attended.23 In my response to Edwards and Leroi, I pointed out that the conference had not come to that conclusion at all.

More importantly, I also addressed the fallacies contained within the assault on Lewontin. Edwards argued that Lewontin’s result (that there is more genetic variation at a given locus within populations than there is between them) was irrelevant because if one examined enough genetic variants an individual’s ancestry could be assigned to a given population.24 Of course, Edwards was just stating the obvious, that there is geographically-based genetic variation within the human species. However, the fact of such variation is not proof of the existence of biological races within our species. Thus as Lewontin pointed out in 1972, while the variation within and between populations is determined by evolutionary forces, in order to identify them one still requires a valid definition of biological race. If one accepts modern definitions of this, which include the amount of genetic variation within and between groups, as well as whether any group can be shown to be a unique evolutionary lineage, then our species does not have biological races.25

Why is There an Ongoing Assault on Lewontin?

Of the many significant contributions that Lewontin made in his career, his analysis of the fallacy of racial classification in humans is one of his most important. It stands on a simple mathematical principle—indeed one that Fisher himself created—the amount of variation within versus among groups. Since the 1970s, subsequent analyses utilizing even more sophisticated genetic methods have consistently demonstrated that Lewontin’s original observation was correct.26 Even more damning for racialist and racist theories of human variation is the fact that most of the genetic variation that exists between groups occurs in non-coding regions of the genome. These segments can accumulate more genetic variation precisely because they do not make any functional proteins and therefore are not exposed to natural selection.27

The accumulation of data has not stopped the attacks on Lewontin. On March 23, 2018, The New York Times published “How Genetics is Changing Our Understanding of Race” by the Harvard geneticist David Reich. This op-ed was an excerpt from his new book, Who We Are and How We Got Here.28 He claimed that Lewontin’s work had led to the formulation of an “orthodoxy” whose primary purpose was to deny the existence of meaningful biological variation between human populations. One of the meaningful genetic differences Reich expected the new genomics to uncover was that of “intelligence” among human populations. Shortly after this piece appeared in The New York Times, and before the book was published, a statement authored by sixty-seven scholars (including myself) ranging from geneticists to sociologists was sent to The New York Times opposing Reich’s formulation of race and its relationship to human society, with the title “How Not to Talk About Race and Genetics.”29 The New York Times refused to publish it, so the piece was eventually published in the popular news outlet, Buzzfeed, on March 30, 2018. Little did I know then that in chapter eleven of his book, Reich felt compelled to call me out by name as a chief defender of the Lewontin orthodoxy. To this charge, I plead guilty.

Why the ongoing attack on Lewontin? To make things simple, they result from the need for neoliberal capitalism (and its apologists) to place the onus of racial oppression on its victims.

So, why the ongoing attack on Lewontin? To make things simple, they result from the need for neoliberal capitalism (and its apologists) to place the onus of racial oppression on its victims. This is why racial biological determinism will always have a place in the beggar’s bowl of neoliberal racialized capitalism. The racists will forever cry that it is not the fact that capitalism will never be able to achieve racial justice, it is the fact that racialized persons suffer from their own deficient genetic potential. Indeed, apologists for neoliberal capitalism continue to argue that it doesn’t matter that human groups share the vast majority of their genetic variants in common, because it is the ones that are strongly differentiated that account for the superior intelligence of Eurasians. This in turn, accounts for why these individuals occupy the highest rungs of social status within capitalism.

The fact remains that there is no scientific evidence to support their claims.30 Of course, when you hold state power, scientific evidence isn’t really a requirement for your claims. However, we should thank Dr. Richard C. Lewontin for providing us with a framework to expose these vicious falsehoods. The rest is now up to us.

About the Author

Dr. Joseph Graves, Jr. received his PhD in Environmental, Evolutionary and Systematic Biology from Wayne State University in 1988. His research in the evolutionary genomics of adaptation shapes our understanding of biological aging and bacterial responses to nanomaterials. He is the author of The Emperor’s New Clothes: Biological Theories of Race at the Millennium (Rutgers University Press, 2005), The Race Myth: Why We Pretend Race Exists in America (Dutton Press, 2005), and Racism, Not Race: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions (with Alan Goodman; Columbia University Press, 2021).

References

- Joseph L. Graves Jr. and Alan Goodman, Racism, Not Race: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021).

- Joseph L. Graves Jr., The Race Myth: Why We Pretend Race Exists in America (New York: Dutton Books 2005).

- Joseph L. Graves Jr., The Emperor’s New Clothes: Biological Theories of Race at the Millennium, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2005); Terence Keel, Divine Variations: How Christian Thought Became Racial Science (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2019).

- Joseph L. Graves Jr., Voice in the Wilderness: How Evolution Can Help Us Solve Our Biggest Problems (New York: Basic Books, 2022).

- Ernst Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1982).

- Graves, Emperor’s, 38–41.

- Louis Agassiz L. and A. A. Gould, Principles of Zoology: Touching on The Structure, Development, Distribution, and Natural Arrangement of the Races of Animals, Living and Extinct (Boston: Gould, Kendall, and Lincoln, 1848); Isabella Duncan, Pre-Adamite Man; or, The Story of Our Old Planet and its Inhabitants, told by Scripture and Science (Edinburgh: W.P. Kennedy, 1860).

- John P. Jeffries, The Natural History of the Human Races (New York: E.O. Jenkins, 1869).

- Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (London: J. Murray, 1871): 214–250.

- Ashley Montagu, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race (New York: Harper, 1942).

- Leslie Dunn and Theodosius Dobzhansky, Heredity, Race, and Society (New York: Mentor Books, 1946).

- Anthony Q. Hazard, Postwar Anti-Racism: The United States, UNESCO, and “Race”, 1945–1968 (New York: Palgrave/MacMillan, 2012).

- Theosodius Dobzhansky, Genetics and the Origin of Species, 3rd ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1951).

- R.A. Fisher, The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1930).

- Dobzhansky, Genetics, 108–134.

- Harry Harris, The Principles of Human Biochemical Genetics (Amsterdam and London: North Holland, 1970).

- Richard C. Lewontin, “The Apportionment of Human Diversity,” in Evolutionary Biology: Volume 6, ed. Theodosius Dobzhansky, Max K. Hecht, and William C. Steere (New York, NY: Springer US, 1972), 381–98.

- Matatoshi Nei and Arun Roychoudhury, “Gene Differences Between Caucasian, Negro, and Japanese Populations,” Science 177 (August 1972): 434-435; Matatoshi Nei and Arun Roychoudhurty, “Genic Variation Within and Between the Three Major Races of Man, Caucasoids, Negroids, and Mongoloids,” Am. J. Human Genetics 26 (July 1974):421-443.

- Richard C. Lewontin, “Biological Determinism as an Ideological Weapon,” Science for the People 9, no. 6 (November/December, 1977): 36-39; Richard Levins and Richard C. Lewontin, The Dialectical Biologist, (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1985).

- Sewall Wright, Evolution and the Genetics of Populations Vol. 4: Variability Within and Among Natural Populations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978).

- A. W. F. Edwards, “Human Genetic Diversity: Lewontin’s Fallacy,” Bioessays 25, no. 8 (July 2003): 798-801doi: 10.1002/bies.10315. PMID: 12879450.

- Armand Marie Leroi, “A Family Tree in Every Gene,” The New York Times, March 14, 2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/14/opinion/a-family-tree-in-every-gene.html.

- Joseph L. Graves Jr., “What We Know and What We Don’t Know: Human Genetic Variation and the Social Construction of Race,” for Is Race Real? a web forum organized by theSocial Science Research Council, published June 7, 2006 http://raceandgenomics.ssrc.org/Graves/.

- Edwards, “Human Genetic Diversity,” 799.

- Joseph L. Graves Jr., “Biological Theories of Race Beyond the Millennium,” in Reconsidering Race: Social Science Perspectives on Racial Categories in the Age of Genomics, eds. in Diego A. von Vacano and Kazuko Suzuki , Reconsidering Race: Social Science Perspectives on Racial Categories in the Age of Genomics (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Franck Prugnolle, Andrea Manica, and François Balloux, “Geography Predicts Neutral Genetic Diversity of Human Populations,” Current Biology 15, no. 5, (March 2005):159-60. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.038; Lori J. Lawson Handley et al., “Going the Distance: Human Population Genetics in a Clinal World,” Trends Genet. 23, no. 9 (September2007): 432-9.; Guido Barbujani and Vincenza Colonna, “Human Genome Diversity: Frequently Asked Questions,” Trends Genet. 26, no. 7, (July 2010): 285-95. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.04.002.

- Seymour Garte, “Human Population Genetic Diversity as a Function of SNP Type from HapMap Data.” Am J Hum Biol. 22, no. 3 (May-June 2010):297-300. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20984.

- David Reich, Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past, (New York: Pantheon, 2018).

- Jonathan Kahn et al., “How Not to Talk About Race and Genetics, Buzzfeed, March 30, 2018. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/bfopinion/race-genetics-david-reich.

- Graves and Goodman, Racism Not Race.