September 20, 2024

Six Decades of Science and Struggle

An Interview with Dr. Donna Mergler

By Jennifer Lee

An abridged French-language version of this article is available in À bâbord ! (numéro 99).

Born to progressive anglophone parents in the dark days of Duplessis’s McCarthyite Québec, Canada, Dr. Donna Mergler grew into her role as both a scientist and an activist as Québec began to free itself from the chokehold of anglophone capital and Québec religious conservatism, during a period of social, political, and cultural effervescence known as the Quiet Revolution.

Dr. Mergler was one of the original faculty members of the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) in 1970, where she was the only woman in the Department of Biological Sciences for the first six years. Working closely with unions and community groups through UQAM’s outreach service to collectives, Donna became an early developer of an interdisciplinary “ecosystem” approach to human health that integrates community leadership, workers’ rights, and gender and social equity. She is internationally recognized for her expertise on the neurotoxic effects of environmental pollutants (solvents, PCBs, manganese, pesticides, mercury), and has authored over 178 peer-reviewed articles on the impact of toxic chemicals on health and well-being. She has received many awards for her work, including the Ordre de Montréal (2020) and Radio-Canada’s Scientist of the Year prize (2023).

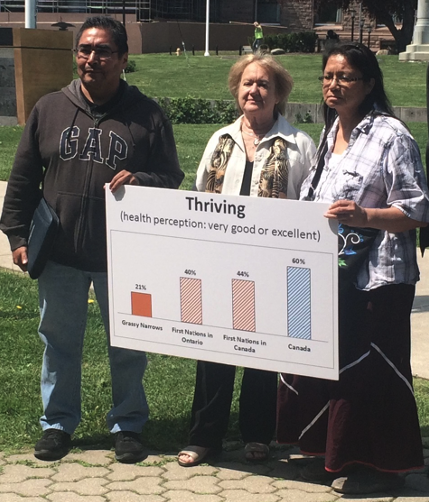

Today, in her eighteenth year of retirement, Donna remains more active than ever at the intersection of science and social justice. She continues a successful community-university partnership with Grassy Narrows First Nation, rigorously documenting the intergenerational impacts of industrial mercury poisoning on their health and well-being. Community leaders have used her scientific work to push for long overdue reforms in disability compensation and long-term mercury treatment and care, advancing Grassy Narrows’s sixty year-long, multigenerational struggle for health, justice, and sovereignty over their land.

She believes that scientists have a duty to speak out about grave injustices, and that the role of scientists is not just to look at the world, but to participate in it. She recently co-authored a declaration in Environmental Health calling for an end to the continuing humanitarian and environmental catastrophe in Gaza.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

—

What was life like as a scientist and an organizer at McGill in the revolutionary 1960s?

Two things were happening in parallel. I graduated in 1965 and started my graduate studies in neurophysiology. I researched the vestibulo-ocular reflex by putting electrodes into cats’ brains to learn about neuronal influx with respect to oscillatory movements. I was using an early analog computer put together by a brilliant technician.

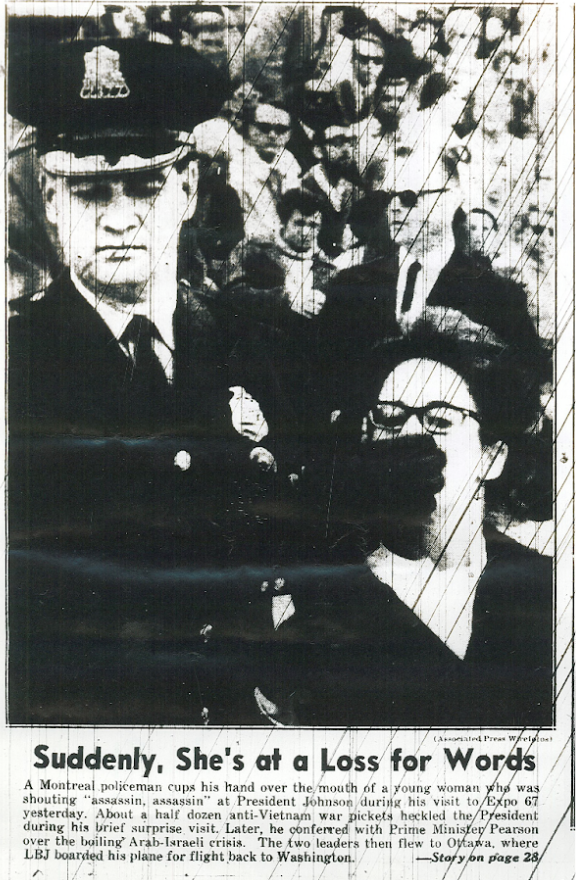

My political activity and my university activity were completely separate. In the day, I would walk up the hill to the McGill Medical Sciences Centre to study and carry out my research. Then, in the evening, I would learn about Québec, about its history, its culture. I would listen to Québec chansonniers, singing about their country and its struggles. I would discuss with friends from the Québec independence movement about justice and equality.

It’s important to understand that the English-speaking Quebecers were in a very privileged position compared to the French-speaking Quebecers. When I was growing up, if you spoke French in one of the big department stores, sometimes, you were not served. The wealthiest people in Montréal were in Westmount, the Golden Square Mile. The more I learned, the more I espoused the independence movement and participated in the frequent demonstrations, including McGill Français, which took place in 1968, where the demand was that McGill become a French-speaking university.

As an anglophone educated in the English school board system, how did you end up involved in Québec’s independence struggle?

I grew up in a very stimulating environment. My father was a progressive lawyer. He represented persons who were arrested for their activities in seeking justice. He had contacts with revolutionaries from around the world. He would bring many interesting people home and we would sit and discuss around the dining room table. I spent hours sitting on the steps of the court where my father was defending Madeleine Parent, a Québec union leader in the 1940s and 1950s. My parents had wanted to send me to a French school, but, at the time, you had to be Catholic to attend the French public schools.

As a student at [anglophone] McGill in the sixties, we were aware of all the liberation movements around the world—I had been to Cuba in 1962—but we knew little about what was happening in Québec. It was the beginning of the Vietnam war. It was also the beginning of the Quiet Revolution in Québec. In 1966, I decided to cross over St. Laurent street—the street that divided English and French Montréal.

I went to the headquarters of the Québec Socialist Party and the Québec Socialist Youth. I discovered a society in effervescence, in movement—culturally, union-wise, politically. Basically, I fell in love with this society. I felt in harmony with what was going on. This was the 1960s! There was the education reform, the health system reform, the union movement that was becoming more and more progressive. This was my place.

UQAM was a direct product of the struggle to democratize education during the Quiet Revolution. What was it like at the very beginning

UQAM was attractive because it was a new university; it had opened in 1969. I was hired by the Department of Biological Sciences. We were young and we did not want to reproduce what we had experienced in other universities. So rather than being a top-down structure like other universities, we created a democratic, bottom-up structure. It took a lot of time, it meant a lot of meetings, but we felt it was worth it.

How did you start doing science in collaboration with unionized mine workers?

In 1975, the Confederation of National Trade Unions (CSN) worked with Dr. Irving Selikoff of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, on a study of the health of Québec asbestos miners. One day, at a party at a friend’s house, one of the union people said, “Well, we have [Selikoff’s] report, and we don’t know what to do with it.” I said, “I’m a physiologist, I can read it and maybe explain it to the workers.”

I read up on the health effects of asbestos, the history of the Johns-Manville mining company, and learned that the company had known since the 1930s that asbestos increased the risk of cancer.1 I began doing workshops with workers—by then, they were striking miners—on the effect of asbestos on their health.

Parallel to this, at the university, we were creating the “Community Outreach Service” (le Service Aux Collectivités), a unique form of university outreach that provides teaching and research for groups who do not have access to university resources. Most universities offer outreach courses for individuals; here, university professors and students could work on co-designed projects for collective embetterment. The first agreement was with two major Québec unions—the Québec Federation of Labour (FTQ) and the CSN. I participated in union-organized workshops on occupational health. Later, agreements were made with women’s groups, environmental groups, and community organizations.

Can you tell us about your work with unionized factory workers?

At one point, I was doing a workshop with solvent-exposed workers from a hockey stick manufacturing plant near Drummondville, Québec. This group was attentive, but the moment I started writing on the blackboard, I’d lose them completely. They’d start joking around. This didn’t happen with workers from other industries. We began to talk about memory loss and difficulty concentrating.

They’d all tell the same story—they’d come in the morning, put down their lunch box and they wouldn’t remember where they’d put it by noon. They said, “It’s worse when it’s hot in the summer.” I said, “That doesn’t sound to me like heat stress!”

So I visited the plant. It took about five minutes before I was high from just breathing in styrene, toluene, n-hexane. And then I had a headache, but I didn’t care, because I was high!

This caught my attention. Here I was: A neurophysiologist faced with a neurophysiological problem. Here was this possibility of combining my academic interests and my desire to help improve workers’ health through changes in the workplace–to act before workers became too ill to work.

The hockey stick workers thought their symptoms were related to heat, but it wasn’t heat. You couldn’t see the solvents, but you could feel the heat. Our role was to validate or invalidate the links that workers were making between their working conditions and their health, and in doing so, we developed a participatory way of doing research.

At this time, the idea of studying early signs of neurotoxicity was relatively new and not considered appropriate by mainstream scientists. During a meeting with union and company representatives from an explosives plant, a well-known epidemiologist hired by the company told us that the study we were proposing on workers was irresponsible. They told us we should be studying illness in retired workers. A young worker intervened saying: “But we want to know what is happening to us now, so that we can make changes.” The plant managers refused to participate and we carried out the study in a motel across the road from the factory.

During this period, my colleague Karen Messing and I started a small research group, which later became the research center CINBIOSE (Centre de recherche interdisciplinaire sur le bien-être, la santé, la société et l’environnement). We integrated workers’ input into our studies, listening to people and translating their situation into rigorous scientific studies, which served to support their demands. For example, our studies helped support the Québec trade unions’ successful fight for certain protections for pregnant and breastfeeding workers, who, in addition to maternity leave, are entitled to job reassignment or an income replacement indemnity in situations where working conditions pose a health threat.

Between 1993 and 2010, I participated in an interdisciplinary and inter-university effort to understand the sources of mercury in the Brazilian Amazon, its transmission through the environment, its effects on health and how social and political forces influenced these pathways. We used a participatory approach working with communities living along the Tapajós River, with a view to maximizing health benefits and minimizing risks. My colleagues in biogeochemistry showed that in addition to mercury discharge from gold mining, widespread deforestation was releasing natural mercury into the river system, where it entered the aquatic food chain.

How did you become involved with Grassy Narrows in Northern Ontario?

In Grassy Narrows, between 1962 and 1975, approximately nine thousand kilograms of mercury were discharged by a pulp and paper mill into the river system that supplies their territorial waters. This mercury was bioaccumulated and biomagnified through the aquatic food chain, contaminating the fish, which were at the center of their culture, livelihood, and diet. Their mercury exposure paralleled that of the fish and was among the highest of freshwater fish eaters in the world. They still remain among the highest in the province of Ontario. Since this time, the people of Grassy Narrows have fought for recognition of their mercury poisoning.

Judy da Silva, who is the soul of mercury justice efforts in Grassy Narrows, asked me in 2016 if I would participate in a community health assessment survey, which they had been requesting for many years. A house-to-house survey, coordinated and administered by community members, was highly successful, with 78 percent household participation. The results showed that both the adults and children of Grassy Narrows were in poorer health compared to other First Nations communities and that prenatal and postnatal mercury exposure contributed to their health problems.2 These findings led to further collaboration on community-driven research; we showed that lifetime mercury exposure contributed to early death as well as symptoms of nervous system dysfunction and their evolution over the past five years.3 A further study showed that intergenerational mercury exposure was associated with an increased risk of suicide, particularly among teenage girls.4 Grassy Narrows has used these studies to support their demands.

When you listen to people, you know what questions to ask. When we began doing participatory research, it was considered unscientific, non-objective. Today, this approach is more and more mainstream, and recognized by most funding agencies.

What do you think the future holds? Are you hopeful?

We are going through a dark period, marked by individualism and the increasing difference between the rich and the poor. What I hope to see in the next few years is the growth of collective movements against injustice and environmental destruction. Support for Indigenous sovereignty and land rights is growing; major battles are being fought, and, one day, hopefully won.

—

Jennifer Lee is a postdoctoral student at TELUQ university, studying environmental health and neurotoxicology. She is an active member of Science for the People.

Notes

- David Kotelchuk, “Asbestos – $cience for $ale,” Science for the People, Vol. 7, No. 5 (September 1975), 8. https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/science/SftPv7n5s.pdf

- Jayme Poisson and David Bruser, “Landmark study reveals ‘clear evidence’ of mercury’s toll on health in Grassy Narrows,” Toronto Star, May 24, 2018, https://www.thestar.com/news/investigations/landmark-study-reveals-clear-evidence-of-mercury-s-toll-on-health-in-grassy-narrows/article_77a64bc2-54d5-56bb-a4dc-2db8c11bed03.html; David Bruser, “Children of Grassy Narrows have higher reported rates of health problems, learning disabilities,” Toronto Star, Dec 5, 2018, https://www.thestar.com/news/investigations/children-of-grassy-narrows-have-higher-reported-rates-of-health-problems-learning-disabilities/article_802511f0-ec41-537c-99b3-61dfc30e41db.html

- Aline Philibert, Myriam Fillion, and Donna Mergler, “Mercury exposure and premature mortality in the Grassy Narrows First Nation community: a retrospective longitudinal study,” The Lancet Planetary Health 4, No. 4 (April 2020), e141-e148, 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30057-7; Aline Philibert, Myriam Fillion, Judy Da Silva, Tanya Suvendrini Lena, and Donna Mergler, “Past mercury exposure and current symptoms of nervous system dysfunction in adults of a First Nation community (Canada),” Environmental Health 21, No. 1 (March 2022), 34, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-022-00838-y; Aline Philibert, Judy Da Silva, Myriam Fillion, and Donna Mergler, “The evolution of symptoms of nervous system dysfunction in a First Nation community with a history of mercury exposure: A longitudinal study,” Environmental Health 23, No. 1 (May 2024), 50, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-024-01089-9.

- Donna Mergler, Aline Philibert, Myriam Fillion, and Judy Da Silva, “The contribution across three generations of mercury exposure to attempted suicide among children and youth in Grassy Narrows First Nation, Canada: An intergenerational analysis,” Environmental Health Perspectives 131, No. 7 ( July 2023), 077001, https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP113