Chapter and Working Group Reports, Spring 2020: Philadelphia

Volume 23, number 2, A People’s Green New Deal

Read more chapter reports in this issue from our Climate Justice Organizing, Western Mass., and the Translation Collective

By Austin Martin

In the early hours of June 21, 2019, a large explosion rocked Philadelphia’s main petroleum refinery, lighting up sections of South and Southwest Philadelphia near the busy Schuylkill Expressway. Caused by a faulty pipe in the refinery’s machinery, the explosion miraculously did not claim lives despite the release of five thousand pounds of deadly hydrofluoric acid.1 This was a watershed moment that warrants a closer look at the conditions of the Philadelphia Energy Solutions (PES) facility and the radical possibilities of the site’s future.

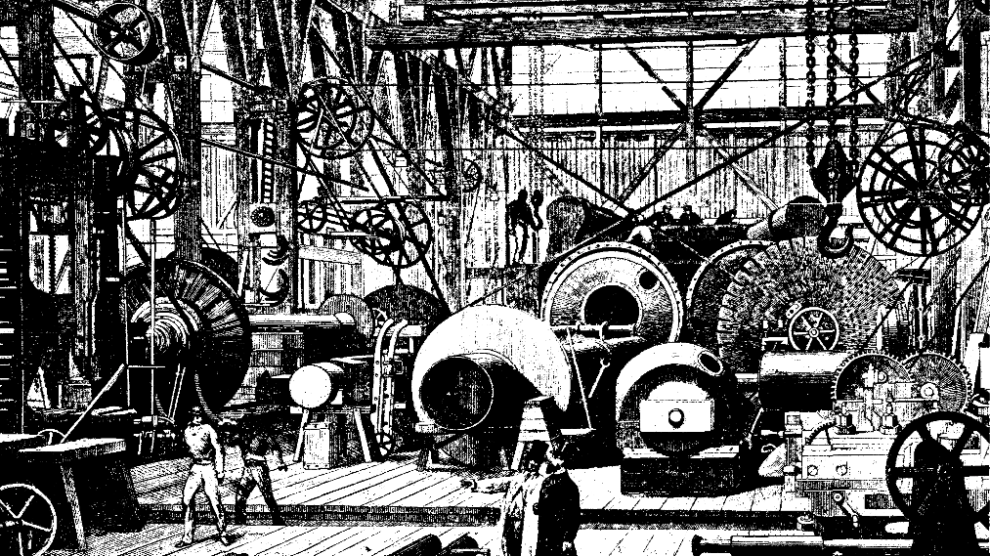

The Refinery’s History

South Philadelphia’s refinery is the oldest and largest on the East Coast of the United States. It is the most significant contributor to greenhouse gas and toxic gas emissions in Philadelphia County and one of the petroleum industry’s worst polluters, responsible for over half the toxic releases in the city.2 Gulf Oil Corporation built the current refinery in 1926, though the site has been active since 1866.3 The site’s history is marked by profound soil and groundwater contamination, where pollutants include gasoline and carcinogenic chemicals like benzene, lead, MTBE, toluene, and benzo(a)pyrene.4

The PES came about in 2012, when then-owner Sunoco entered a joint venture with the Carlyle Group, one the world’s largest private equity firms specializing in leveraged buyout transactions. The refinery went bankrupt in January 2018, with ownership citing burdensome compliance costs.5

The State Sustains the Interests of Fossil Fuels

The series of institutional crises and restructurings that led to PES ownership of the refinery was not only determined by market dynamics. The state was centrally involved in propping up the refinery through a reworking of regulatory frameworks, or what Peck and Tickell have called a “search for a new institutional fix.”6 In the years 2012 to 2015 alone, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania provided the refinery with $25 million in cash grants and a variety of other forms of support that include designating a Keystone Opportunity Zone, extending tax-exempt bonds, consenting to a decree allowing air quality violations, and issuing a legal agreement protecting PES from liability of groundwater contamination.7

The refinery’s recent history of institutional rearrangement shows how capital accumulation requires and receives an undergirding of state support. The government provides an endowed shelter for fossil fuel companies to get beyond their current and long-term capital crises. In the case of PES and its refinery, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and City of Philadelphia, under the Democratic oversight of the Obama and Nutter Administrations, spent millions of dollars underwriting a declining and already subsidized industrial asset, despite the City of Philadelphia’s attempt to outline a climate mitigation plan.8 In Philadelphia, environmental justice organizations like Philly Thrive must focus on the state’s ongoing role in supporting its local fossil fuel infrastructure. As the climate justice movement fights to reimagine local and regional energy systems, our strategy must engage with the central importance of the state and its current unjust approach.

- US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, “Fire and Explosions at Philadelphia Energy Solutions Refinery Hydrofluoric Acid Alkylation Unit,” 2019.

- “#WeDecide Our Energy Future Survey Report,” Philly Thrive, 2017, http://www.phillythrive.org/_survey_report.

- Christina Simeone, “Beyond Bankruptcy: The Outlook for Philadelphia’s Neighborhood Refinery,” Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, University of Pennsylvania (2018):64; National Park Service, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form,” 1870.

- Christina Simeone, “Beyond Bankruptcy: The Outlook for Philadelphia’s Neighborhood Refinery,” Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, University of Pennsylvania (2018):64; National Park Service, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form,” 1870.

- Christina Simeone, “Beyond Bankruptcy: The Outlook for Philadelphia’s Neighborhood Refinery,” Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, University of Pennsylvania (2018):64; National Park Service, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form,” 1870.

- Jamie Peck and Adam Tickell,“Searching for a New Institutional Fix: The After-Fordist Crisis and the Global-Local Disorder,” in Post-Fordism, ed. Ash Amin (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2014): 280-315.

- Christina Simeone, “Beyond Bankruptcy: The Outlook for Philadelphia’s Neighborhood Refinery,” Kleinman Center for Energy Policy, University of Pennsylvania (2018):64; National Park Service, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form,” 1870.

- The City of Philadelphia Office of Sustainability, Powering our Future: A Clean Energy Vision for Philadelphia,https://www.phila.gov/documents/powering-our-future-a-clean-energy-vision-for-philadelphia/