Reclaiming Epistemic Diversity

Between Community Struggles and Corporate Capture

By David Ludwig, Fabio Gatti, Esther Milberg Muñiz

Volume 26, no. 2, Ways of Knowing

When anti-colonial revolutionary Amílcar Cabral proclaimed a “return to the source” through “re-Africanization” in Guinea and Cabo Verde, the Portuguese colonial empire was stumbling towards its inevitable collapse.1 Although the military defeat of the fascist Estado Novo regime remained the priority in 1972, Cabral anticipated that national independence would not lead to cultural liberation if it did not challenge “the pretended supremacy of the culture of the dominant power over that of the dominated people.”2 Defeating the Portuguese militarily had to be accompanied by cultural liberation to not preempt a shift from direct colonial domination to indirect neocolonial hegemony.

Cabral understood that denying the knowledge of the oppressed was foundational to colonial oppression but also to the emerging neocolonial regimes of international development. While the Portuguese were still clinging to military occupation in the 1970s, most African nations had gained independence and many colonizers had already turned into development actors instead. Where “development programs” replaced crumbling narratives about a “civilizing mission” of colonialism, epistemic hierarchies remained strikingly stable. Within these programs, developmentalist narratives were framing communities across the continent as passive beneficiaries of western knowledge, without relevant epistemic agency on their own: knowledge was still exclusively the domain of the former colonizers and therefore to be exported to the formerly colonized. Indigenous cultures were still the target of eradication, as they were not recognized as a source of legitimate knowledge but rather a tribalist obstacle to modernization and progress.

Cabral’s “return to the source” reflects how the colonial imposition of epistemic monocultures serves political oppression, but also how the cultivation of epistemic polycultures becomes a strategy for political emancipation. Stories of different ways of knowing are therefore often both stories of resistance and of liberation. Situating Cabral’s “return to the source” in contemporary academic discourses about epistemic diversity, however, also highlights more ambiguous relations between ways of knowing and liberatory practice. While epistemic diversity is becoming mainstreamed in academia, it has been simultaneously sanitized from political struggles. Different ways of knowing are increasingly embraced by a burgeoning academic literature on “Indigenous,” “local,” “traditional,” or otherwise “marginalized” knowledges. At the same time, these ways of knowing are commonly separated from liberatory practices and inserted into tame academic exercises that advance academic careers and discourses rather than community struggles and livelihoods. Epistemic diversity has been captured by academia. And it is time to reclaim it.

Capturing Epistemic Diversity

Philosophers are preaching “scientific pluralism,” anthropologists are studying “Indigenous knowledge systems,” conservation biologists are integrating “traditional ecological knowledge,” development actors embrace “multi-stakeholder platforms,” and bureaucrats ensure that “diversity and inclusion” becomes central to the university branding. Epistemic diversity is becoming a booming business in academia. Far from realizing a Cabralist vision of liberatory practice, however, the mainstreaming of epistemic diversity reflects that it has been captured by decoupling community knowledges from community struggles. Multiple/different/pluralistic ways of knowing are ubiquitous, but their function has become to support dominant academic institutions rather than to disrupt them.

Capturing epistemic diversity operates through two core mechanisms: knowledge extraction and symbolic inclusion. In the first case, diverse knowledge gets captured by being reduced to supplementary data for academic consumption. This mechanism has been widely identified by Indigenous scholars, including Potawatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer, who writes: “Knowledge mining or the extraction of useful facts from the body of knowledge, without exploration of the cultural context in which they belong, can do a disservice to the information as well as to the culture.”3 In the second case, institutions legitimize themselves through superficial appeals to community knowledge, without supporting communities and their struggles in any meaningful way. Extracting “useful” knowledge about biodiversity conservation from Indigenous communities, for example, is framed as a step towards more inclusive research and conservation practice, even if this knowledge is assimilated into dominant research agendas without any tangible benefits for the Indigenous communities from which knowledge emerges.

The first mechanism of knowledge extraction is most salient in cases of biopiracy, which involves exploiting genetic resources for external profit. Biopiracy has a long history as a tool of colonial extraction. For example, Indigenous peoples across the Americas had long known about properties of rubber trees (as documented in European accounts of Indigenous use of rubber to waterproof clothes or the use of a rubber ball in the Mesoamerican game of ōllamaliztli). The commercialization of rubber in the 19th century, however, did not benefit Indigenous people. On the contrary, the rapid growth of rubber production across the Amazon basin was built on the dispossession of Indigenous land, forced labor of Indigenous peoples, and massacres such as the Putumayo genocide orchestrated by the Peruvian Amazon Company.4

While knowledge extraction is most striking in commercial cases of biopiracy, capturing epistemic diversity within the academe often proceeds in more subtle ways.

Biopiracy remains at the center of many blatant cases of commercial exploitation of epistemic diversity. When the weight loss supplement TrimSpa entered the market in the early 2000s, for example, it relied on an extract from the plant Ephedra sinica, which had been used in traditional Chinese medicine for more than 2000 years. Heavily promoted by celebrity spokesmodel Anna Nicole Smith with the slogan “It’s TrimSpa, Baby!”, the supplement accumulated revenues of $43 million in 2004 alone but ran into regulatory trouble when the US government announced a ban on ephedra products due to health concerns. The company switched to Hoodia gordonii, a plant that had long been used by the San people of southern Africa during long hunting journeys.5 While San people did not benefit from this commercialization and the active component known as P57 remained academically contested, the exotic appeal of extracted Indigenous knowledge had already turned it into a multi-million dollar industry. Biopiracy thus demonstrates that recognizing community knowledge does not always translate into benefits for communities or liberatory practices. It is entirely possible to recognize epistemic diversity and then exploit it for the creation of a questionable weight loss supplement.

While knowledge extraction is most striking in commercial cases of biopiracy, capturing epistemic diversity within the academe often proceeds in more subtle ways, even as it is executed by well-meaning researchers with genuine concerns about issues such as biodiversity conservation or climate change. For example, when scientists turn to traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) for biodiversity conservation, the goal is usually not commercial exploitation. Instead, conservation biologists have increasingly come to recognize community expertise about a variety of issues such as changing ecosystem dynamics or population health. Still, while the integration of traditional ecological knowledge into academic frameworks can contribute to the efficiency of conservation management, it often does very little for communities. As academic interests become the measure for the usefulness of community knowledge, knowledge integration will often fail to generate tangible benefits for communities. For example, an Indigenous community may have relevant information for an academic research project that aims to assess the local conservation status of a vulnerable species, but sharing that information may not produce any relevant return for communities. Instead of establishing reciprocal relationships, sharing information about vulnerable species may even legitimize policies that further marginalize communities by criminalizing their livelihood practices such as hunting, fishing, or farming.

Knowledge extraction constitutes a powerful mechanism for separating community knowledge and community struggles. This captured epistemic diversity becomes politically tamed because isolated fragments of “useful knowledge” can be integrated into dominant academic frameworks without serious engagement with the livelihoods, struggles, or worldviews of communities. This does not mean that captured epistemic diversity has no political functions. On the contrary, knowledge extraction is intertwined with the second mechanism of symbolic inclusion, which allows for political legitimization instead of disruption.

Political philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò has described “elite capture” as a strategy that inverts the political function of identity politics from institutional disruption to legitimization through the inclusion of a selected few who are treated as representatives of the marginalized.6 Elite capture allows institutions to build symbolic legitimacy through the inclusion of a university president, a police chief, or a CEO from a marginalized group without transforming institutions or disrupting systemic processes of marginalization. Captured epistemic diversity often supports and further escalates this process of elite capture by allowing for the inclusion of marginalized knowledge without having to deal with the inclusion of any marginalized people whatsoever. Researchers can symbolically showcase their commitment to diversity and inclusion by studying the knowledge of Indigenous people, or even organizing participatory workshops in the field as a means of co-creating research, without actually letting anyone from the communities anywhere near positions of institutional power in academia.

Liberatory Ways of Knowing

What would it take to resist academic capture of community knowledge? One seductive answer is to frame modern science exclusively as a reductive and extractive tool of oppression while embracing Indigenous knowledge as a holistic and regenerative alternative.7 Especially in the face of commodified research that serves capitalist exploitation, one may be tempted to position academic and Indigenous knowledge in strict opposition to each other in order to avoid capture of the latter.

Such a simple divide, moreover, misrepresents the complex epistemic coalitions that actually support liberatory practices. In the case of Cabral, discussed in the introduction, the “return to the source” is not a simple turn away from science. Cabral’s case for “re-Africanization” does primarily demand “development of a popular culture and of all positive Indigenous cultural values.”8 However, instead of a wholesale rejection of science in favor of Indigenous knowledge, Cabral’s call for popular Indigenous culture is paired with a simultaneous endorsement of the “development of a technical, technological, and scientific culture, compatible with the requirements for progress.”9 As an agronomist trained in colonial agriculture at the University of Lisbon, Cabral’s “return to the source” is based on a complex understanding of the power of science as a tool for both oppression and liberation. Colonial agriculture was key to the exploitation and destruction of Indigenous culture but agronomy was also indispensable for achieving self-sufficiency and food security in a liberated Guinea and Cabo Verde. For Cabral, Indigenous and scientific knowledge are not paradigms in perpetual conflict, but both to be mobilized together for national liberation.

Cabral’s liberatory appeal to different ways of knowing converges with Paulo Freire’s reflections on the conditions of liberation in Brazil. Having gained independence from the Portuguese empire more than a century before Guinea and Cabo Verde, national independence in Brazil did not produce cultural liberation. Writing his Pedagogy of the Oppressed in exile after the reactionary military coup of 1964, Freire analyzes how the denial of popular knowledge and popular education represents one of the core mechanisms of oppression. As stated by a peasant in one of Freire’s interviews, the oppressor is “the only one who knows things and is able to run things.”10 Oppressive education builds both on the systematic denial of different ways of knowing and on tight control over an epistemic monoculture that shapes science and technology through the interests of the oppressor. In the technocratic modernity of the Brazilian military dictatorship, scientific monoculture therefore relentlessly pushes for increased efficiency and productivity in the exploitation of peoples and environments.

As an agricultural engineer, Cabral did not simply reject scientific culture in favor of Indigenous culture but rather imagined a polyculture of knowledges mobilized for national liberation. Similarly, as the architect of a national alphabetization campaign that was crushed by Brazil’s military dictatorship, Freire did not reject the knowledge of the oppressor in favor of the knowledge of the oppressed. The alternative to oppressive monocultures of technoscientific capitalism is not to claim that peasants already know everything or to reject alphabetization as a tool of oppression. Neither, crucially, is the alternative a tame pluralism in which the knowledges of the oppressor and the oppressed are put next to each other in false harmony. Instead, liberatory dialogues are needed that aim at the transformation of the knowledge of both oppressor and oppressed.

Cabral and Freire are reflexive about the oppressive functions of scientific monocultures without reducing modern science to only a tool of oppression. The goal is neither apologetics nor rejection of science but rather its (re)orientation towards liberatory practice. Both Cabral and Freire encounter science systems that are not oriented towards liberation but instead structured to organize oppression by the Portuguese Estado Novo regime and the Brazilian military dictatorship. Similarly, the current science system of commodified universities and science managers is not oriented towards liberation either. Neoliberally-structured universities, on the contrary, are oriented towards the goals of their funders that are often directly adversarial to liberatory struggles of communities whose “ways of knowing” are captured as merely symbols of diversity. The capture of epistemic diversity is therefore not the result of individual transgressions, but of commodified research agendas that embrace different ways of knowing only when they support the goals of research funders.

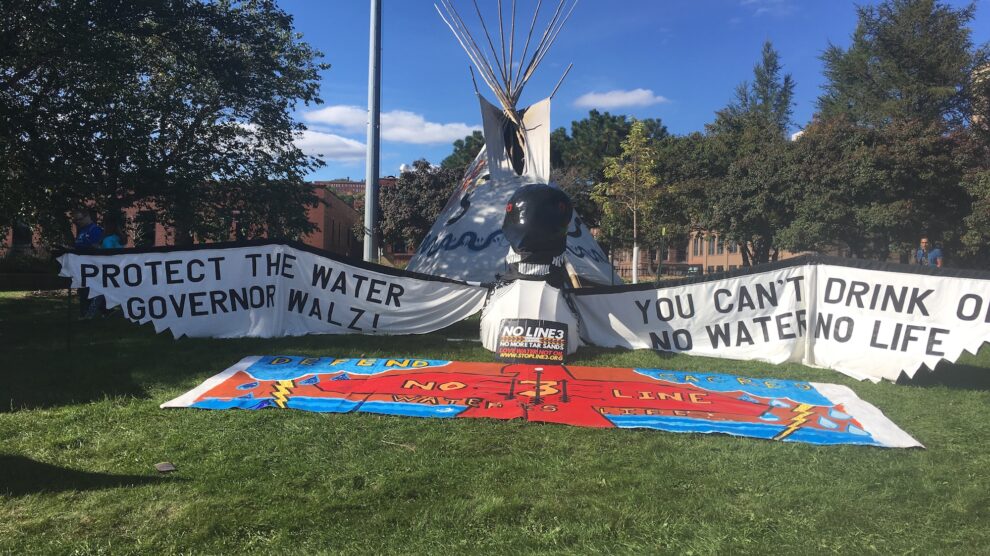

While academia de-radicalizes epistemic diversity through capture, the orientation of “ways of knowing” towards liberatory practice becomes most salient in social and political movements outside of commodified universities. Consider, for example, the case of the Zapatista movement whose armed uprising in 1994 responded to the dispossession of indigenous peoples in Chiapas based on agricultural intensification and the neoliberalization of global agrifood markets. Again, agricultural sciences reveal their force as powerful tools of oppression that contribute to transforming Chiapas into a frontier of natural resource and labor extraction, through de-Indigenization. Again, a “return to the source” of Indigenous culture drives resistance against oppression. As the “Fourth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle” calls for “a world in which many worlds fit”, Indigenous knowledge is centered in resistance against the monoculture of technoscientific capitalism.11

Furthermore, the Zapatista call is not about disconnected worlds in which Indigenous and scientific knowledges are neatly separated and opposed to each other. On the contrary, Zapatista strategies of internationalist mobilization reflect a dynamic vision of epistemic exchange across different ways of knowing that, importantly, also include modern science. In 2016 and 2017, the Zapatista movement organized two events — the ConCiencias por la Humanidad — where scientists and Indigenous Zapatista people sat at the same table to exchange knowledge able to contribute to the fight for life (la lucha por la Vida) against the multifaceted capitalist monster (la Hidra Capitalista).

Rather than a complete rejection of academic knowledge, the events showed interest in the work of scientists, and expressed the need for science “in order to be able to keep developing as Zapatistas.”12 But, as a participant put it, their attention was directed toward science and technology “able to build something for the benefit of all,” instead of studying Indigenous peoples for the benefit of academic research and publications.13 At the same time, the scientific community was criticized for its disconnection from the struggles of Indigenous peoples. Stressing the importance of being united in the struggle against capitalist exploitation and supportive of their fight for survival, the Zapatistas who were participating in the event kept asking the audience: for whom are you (the scientist) doing your science? To whom are you presenting your “results”? Who benefits (and who loses) from your alleged discoveries?

The recognition of community knowledge often becomes politically tamed through knowledge extraction that turns epistemic diversity into a resource of institutional legitimization in the place of disruption.

Similar to Cabral’s and Freire’s strategies, the Zapatista attempt was to mobilize Indigenous and scientific knowledge together for liberation purposes. The goal was, in other words, to build an alliance across different epistemic communities for creating a new form of knowledge that could contribute to a common struggle, namely the liberation of Zapatista people and other oppressed people all over the world from the yoke of neoliberal capitalism. As clearly expressed by one of the young Zapatistas intervening at the meeting: “We need to get organized together. We can only destroy the capitalist monster when ‘scientific science’ (la ciencia científica) allies with ‘the people’s science’ (la ciencia de los pueblos).”14

Reclaiming Epistemic Diversity

Instead of merely praising epistemic diversity, it is time to reclaim it. Our contrasting stories of captured and liberatory uses of epistemic diversity demonstrate that it is not enough to recognize different ways of knowing. The useful/meaningful question is not whether there are different ways of knowing but how they are related to the material interests of different actors. Our stories of captured epistemic diversity reflect that recognizing knowledge of the people does not by itself generate a science for the people. Instead, the recognition of community knowledge often becomes politically tamed through knowledge extraction that turns epistemic diversity into a resource of institutional legitimization in the place of disruption. All we may get out of captured epistemic diversity is another weight loss supplement claiming to be based on Indigenous knowledge or a nicely designed corporate responsibility brochure with Indigenous people on the cover.

Our three stories of liberatory ways of knowing, however, also point to a more hopeful message. It does not have to be epistemic diversity that is captured by academics, it can also be academic knowledge that is captured for liberatory practice. Despite many differences between Cabral, Freire, and the Zapatistas, all three cases exemplify an inversion of the logic of captured epistemic diversity: instead of requiring that community knowledge proves its usefulness in academia, academic knowledge is challenged to prove its usefulness to communities. From Cabral’s “return to the source” to the Zapatista call for “a world in which many worlds fit”, epistemic diversity becomes a “leverage for freedom” when mobilized through community struggles rather than academic research agendas.15

Although academic discourses about epistemic diversity and scientific pluralism are becoming thoroughly mainstreamed, they often retain elements of a political promise to challenge the status quo of academia.16 Even in its captured academic form, epistemic diversity remains associated with the promise of diversifying knowledge production beyond epistemic monocultures that universalize one dominant way of knowing. Political commitment to this promise, however, requires a critical examination of the booming academic literature on Indigenous, local, traditional, or otherwise marginalized knowledges. Not because these knowledges do not matter, but rather because their instrumentalization for academic purposes separates them from their social and political function for marginalized communities.17 Rather than demanding that community knowledge becomes integrated into dominant academic frameworks, our stories of liberatory practices invert this demand by centering on knowledge production that serves communities and their struggles.

Meet the contributors:

David Ludwig (Ph.D): David Ludwig is a philosopher and transdisciplinary researcher focussing on methods for community-based research and transformative science. He’s an associate professor at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/davidludwig.bsky.social

Fabio Gatti (MSc, MA): Fabio Gatti is a PhD Candidate in the Knowledge, Technology and Innovation group (KTI) of Wageningen University., and member of the Global Epistemologies and Ontologies research collective (GEOS). Twitter: FabioGatti86

Esther Milberg Muñiz: She is a passionate advocate for a more just, diverse, and social-politically relevant science. She studies transdisciplinary processes as a science, a practice and a movement, working with feminist and agroecological movements in Latin America. Beyond academia, she cultivates community gardens, plays in a feminist Latina band, and experiments with documentary filmmaking.

Luzángela Brito: Garabatoslux is a project created by Lux, a Guajira wanderer and illustrator: a vehicle for converting experiences into marks on a page. Lux/Garabatoslux soaks up their surroundings: the people, the identities, the customs, the traditions, the faces of the Carribean, the real histories that are maintained by culture and made known, in this case, through drawing. IG: @garabatoslux

Notes

- Amílcar Cabral, Return to the Source, (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2022), 65.

- Cabral, Return to the Source, 127.

- Robin Wall Kimmerer. “Searching for synergy: Integrating traditional and scientific ecological knowledge in environmental science education.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 2 (2012): 317-323.

- Boletín Temático Servindi. La fiebre del caucho y los crímenes del Putumayo. (Lima, Perú, 2012). https://docplayer.es/6018066-La-fiebre-del-caucho-y-los-crimenes-del-putumayo.html.

- Lere Amusan (2017). Politics of biopiracy: An adventure into Hoodia/Xhoba patenting in Southern Africa. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines, 14(1), 103-109.

- Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Elite Capture, (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2022).

- Arun Agrawal (1995). “Dismantling the divide between indigenous and scientific knowledge.” Development and Change 26, 413-439.

- Cabral, Return to the Source, 96.

- Cabral, Return to the Source, 97.

- Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, (New York: Continuum Publishing, 2005), 63.

- Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, Cuarta Declaración de la Selva Lacandona, 1996. https://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/1996/01/01/cuarta-declaracion-de-la-selva-lacandona/.

- Participant’s intervention, from author’s field notes. Conciencias por la Humanidad, CIDECI – San Cristóbal de las Casas, December 2017.

- Participant’s intervention, December 2017.

- Participant’s intervention, December 2017.

- Joy James. “The womb of Western theory: Trauma, time theft, and the captive maternal.” Carceral Notebooks 12.1 (2016): 253-296.

- David Ludwig and Stéphanie Ruphy. “Scientific pluralism.” (2021) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/scientific-pluralism.

- Kyle Powys Whyte, “What do indigenous knowledges do for indigenous peoples?”, in: Traditional Ecological Knowledge, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2018).