Disruptions and Reproductions of Normative Science

The Autobiography of the Transgender Scientist (2017)

By Prerna Srigyan and Neak Loucks

Volume 26, no. 1, Gender: Beyond Binaries

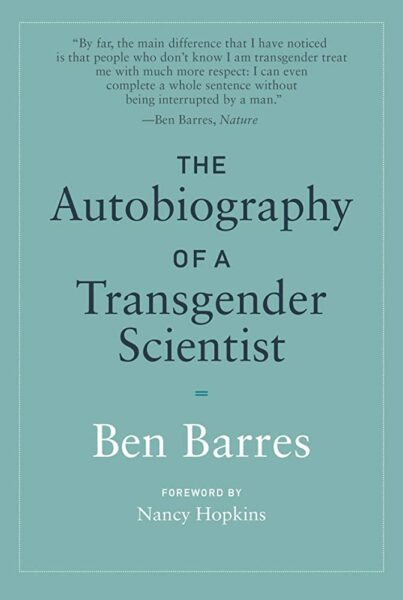

We learn from Nancy Hopkins’s foreword and numerous articles published after his passing in late 2017 that Ben Barres (1954-2017) was a beloved colleague, mentor, and celebrated scholar.1 His lab advanced understanding of the active role of glial cells in neurobiology, considered before to only play a passive role in neuron and synapse function. As a transgender scholar, he remained, to the end of his life, a passionate advocate for underrepresented communities in science, maintaining that science takes an immeasurable hit when women and LGBTQ folks are prevented from doing science and making scientific careers.

Divided into three chapters, his autobiography offers a narration of his educational and career trajectory including some of the personal factors shaping that trajectory (“Life”); a summary of the innovative neurobiological research carried out by Barres, his trainees, and other collaborators (“Science”); and a brief discussion of his advocacy work within scientific communities (“Advocacy”). Like the articles posthumously celebrating Barres’s life and work, this book’s title, cover, and synopsis highlight Ben’s advocacy and his transness. For instance, it showcases a quote from his influential article in Nature, “Does Gender Matter?”, that describes how people reacted to him differently when they perceived him simply as a man.

Hopkins describes Barres as a “radical activist,” a position built from the experience of being read first as a woman and, later, as a man within academic and scientific research settings. Indeed, Barres has a strong record among scientists of speaking and acting against gender bias and sexual harassment in scientific communities. Yet, as readers (and as ethnographers), we are met with tensions within the text regarding how his activism and experience as a transgender person relates to his scientific practice—at times reading as auxiliary to what is primarily a story of a scientist’s life and passion for science and at times seeming central to that story. We explore these tensions by asking where the “radical” can be found in his narration and considering Barres’s voice within the broader contexts of his life trajectory. We encourage readers to journey through Barres’s self-narration with active curiosity toward how this text interweaves disruptions and reproductions of normative academic and scientific cultures and to build mental bridges to other registers of activism that unfold in the wake of Barres’s legacy.

Barres was well-known as a vocal advocate against gender bias in science, leveraging his positions as a senior scientist and white man to agitate the field in ways that would have been received much differently from women and/or junior scholars. Within the text, neither this advocacy nor his marginalization is a central focus of the book. Ben’s narration, however, shows that he disrupted normative science by simply existing in elite scientific institutions where white, cisgender, heterosexual men are the default. His interest and persistence were supported by new science education initiatives aiming to address Cold War anxieties about the quality of American science. In the autobiography, Ben recounts the joy he experienced in attending National Science Foundation (NSF) funded programs like a summer internship program at Phillips Andover Academy and Science Honors Program at Columbia University, learning about the latest scientific problems and acquiring valuable skills like computer programming. Moreover, newly established corporate scientific research centers like Bell Laboratories became influential in training many minority scientists through their Corporate Research Fellowship Program (CRFP).2 Participating in all of these spaces while being seen as a woman, Ben was a trailblazer on newly opened pathways for people other than cisgender white men to become scientists, albeit supported by programs fueled by nationalistic and militaristic goals.

We read Ben’s commitment to quality mentoring and collegiality as another form of disruption of default modes of scientific engagement. He learned many mentoring practices from his mentors, who appear in his autobiography as figures devoted to science who were able to look beyond Ben’s gender and recognize his talent and drive. He was frustrated by how little mentoring many young and early-career scientists received, even within the elite scientific institutions where he completed his degrees. He was also opposed to practices like advisors extracting graduate labor to further their own careers, forbidding advisees to collaborate under the notion of proprietary data, and discouraging them from leaving with their doctoral and postdoctoral projects to start new labs, seeing such practices as hampering scientific innovation. Instead, learning from his own mentors, he encouraged his students to explore multiple collaborations and sites of learning; scaffolded high-risk work that enabled them to explore new scientific methods and questions; and modeled how to maintain active correspondence with colleagues, former students, and academic and funding administrators. Ben’s autobiography models a vision of science that casts mentoring and teaching not as superfluous but rather as central to quality knowledge production.

Ben’s narration, however, shows that he disrupted normative science by simply existing in elite scientific institutions where white, cisgender, heterosexual men are the default.

Another important way that Ben disrupted normative science was by establishing scientific training programs that intervened in the hierarchy of basic versus applied research. In the autobiography, he is angered that disease research and clinical practice are treated as second-class activities in science. Expressing that “something is broken…there is a desperate need for new (and better) scientists to engage in these problems,” he lamented that aspiring and current physician-scientists do not receive the support they need. The disconnect between basic and applied research led him to start the Masters of Medicine (MOM) program at Stanford University that trains incoming PhD students in human biology and disease so that basic scientific research and clinical treatment can advance in parallel.

In other ways, Barres’s autobiographical account unintentionally reproduces facets of normative science and academia. Ben humbly acknowledges the financial and mentoring support that enabled him to accumulate “science capital”3 despite experiencing sexism while seen as a woman. In the narrative of his early educational experiences, however, the impact of his close proximity to multiple prestigious institutions offering free or scholarship-covered programs goes unremarked, leaving unexamined one well-worn pattern of access and exclusion: how geographic location can greatly shape the learning opportunities available to an individual. By taking geographic location for granted, the text leaves in place normative assumptions of science as a spaceless practice.

Though seemingly driven more by passion than by pressure, Ben’s habits of staying in the lab until the wee hours of the morning and abruptly leaving vacations to return to work reproduce idealized rhythms of academic knowledge production that hamper the participation of scientists and academics with disabilities or caregiving responsibilities. This mode of engagement is not in itself inherently harmful, but it goes unexamined in the text—as in many scholarly settings—that the ideal academic mind-body is fully-abled with little to no caregiving responsibilities that would hamper one’s ability to perpetually prioritize the labor of knowledge production. Success and promotion within academic structures is often measured against the productivity of this imagined ideal being. We point out these facets of the narrative not as critique of Ben’s life experience or self-narration but rather to frame the book as an artifact that spurs a meditation on how radicality and normativity are interwoven within individual threads of participation in scientific practice, reminding us of the need for bringing varying threads of advocacy in conversation with each other.

This tension between challenging and reproducing normative science is also apparent in Ben’s ambiguity about when and how his transness matters. When Ben turns to gender at points throughout the book, the reader glimpses Ben’s emotional pain of living at odds with his sense of self, as well as his emotional distance from personal experiences of gender bias when seen as a woman. Outside of these sections, he narrates his educational and professional engagement, both before and after transitioning, with little discussion of gender or transness. For much of the text, it can feel as if one message of this “autobiography of a transgender scientist” could be that the transgender facet of his life is unremarkable in relation to his scientific practice. And yet, looking beyond this text alone, we know from Barres’s advocacy in scholarly communities and in publications like “Does Gender Matter?” that his transness was a central catalyst in his advocacy:4 it was not his experience as a woman in science that distilled his awareness of gender bias in the field, but rather his experience as a woman and then as a man.

Where Ben’s experience with gender is discussed, he remains haunted by the biological basis of his transgender experience, searching for answers about gender and sexuality at the genomic level. Such a lens may land at odds with some contemporary queer and trans readers, particularly in the ways that Ben’s hypothesis about why he was trans centers a theory that veers toward reinscribing essentialist notions of masculine and feminine brains. Yet, this perspective might be understood as part of his radicality if examined in context. Ben’s trans “coming of age”—that is, when and how he learned to understand his gender confusion and transitioned socially and medically—played out through the 1990s and early 2000s.

Gender and sexuality research at the time turned toward genetics, searching for “the gay gene” and hypothesizing about the in utero effects of hormones of sexuality. The scientific desire to understand non-heterosexual desire as a form of natural genetic and epigenetic variation is not by itself an inherently queer-affirming framework (for example see Murphy [1997] discussing the ethics of sexual orientation research).5 Yet through this same period, genomic framing of queerness joined a constellation of ideas resisting previous medical and scientific characterizations of queerness as disorder and perversion.

Though Barres speaks of his own trans experience using an explanatory framework that suggests genetic and epigenetic differences between male and female brains, he was not reproducing the biological essentialism seen in dubious evolutionary psychology claims of Larry Summers, Steve Pinker, and James Damore who framed women as biologically inferior to men. While he was committed to a particular neurobiological explanation of his gender experience, this commitment did not conflict with a strong assertion that there are no gender differences that are relevant to an individual’s ability to do scientific research. That gender bias was central in Ben’s advocacy because he felt so strongly that gender doesn’t determine one’s ability to practice science offers clarity on Ben’s vision of science.

Ben’s vocal opposition to bias in science was driven by a sense of fairness—a belief that people of all identities are capable and should have full opportunity and access to participate in science. In the narration, however, matters of access and knowledge production are bifurcated: subjectivity and exclusion come to matter in the former but not in the latter. Ben’s personal experience as a trans person matters in how he mobilized as an advocate to get people in to the realm of scientific practices, but we are given the impression that within scientific knowledge production, lived experiences are irrelevant—that the scientist themself is essentially an interchangeable agent, provided they have sufficient training to produce reliable results.

[His] commitment did not conflict with a strong assertion that there are no gender differences that are relevant to an individual’s ability to do scientific research.

As readers, we are left with a sense that his transness, as a researcher and a participant in a scholarly community, dances between being remarkable and unremarkable. His scientific practice both demonstrates a departure from his contemporaries and remains committed to framing identity as a barrier to science to be resolved by representation. Yet, as feminist standpoint theory reminds us, knowledge from a location strengthens, rather than weakens, objectivity.6 Further, representation alone cannot be enough to enact structural change if it serves capitalistic and militaristic pursuits (Benjamin 2019).7 Ben’s autobiographical account of a life in science weaves together disruptions and reproductions of science that can be interpreted historically and serve as an evocative artifact in contemporary conversations. We wonder what Ben would have thought about the current STEM organizing afoot in scientific industrial and academic workplaces that directly challenges the political economy of normative science by foregrounding labor power, gendering, and racialization in science labs.8 How might he have participated in not only being a radical advocate in science, but in doing radical science?

Meet the Contributors

Prerna Srigyan is an anthropologist and educator working as a Ph.D. Candidate at UC Irvine Department of Anthropology and as a researcher at the UCI EcoGovLab. Her research is on comparative pedagogical cultures of science, examining how, where, and why pedagogy is designed and mobilized for radical and critical activation. She builds educational and pedagogical frameworks for recognizing, characterizing, and addressing environmental and social injustices at the university and K-12 levels.

Neak Loucks is an anthropologist and educator. Their dissertation research focuses on settler engagements with land and place in Southern Utah, detailing how settler colonial frameworks reverberate through American public lands management and land conflict. In examining practices of contested place-making, Neak illustrates how commitments to idealized places influence people’s interactions with data and expertise. As an instructor, they are particularly interested in improving inclusion and accessibility at scales ranging from curriculum design to institutional policies.

Endnotes

- Freeman, Marc. “Ben Barres: Neuroscience Pioneer, Gender Champion.” Nature 562, no. 7728 (October 22, 2018): 492–492. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07109-2.; Goldman, Bruce. “Neuroscientist Ben Barres, Who Identified Crucial Role of Glial Cells, Dies at 63.” Stanford Medicine News Center, January 18, 2017.

- Anirban, Ankita. “Black Scientists at Bell Labs.” Nature Reviews Physics 4, no. 7 (July 2022): 424–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-022-00488-6.

- Archer, Louise, Emily Dawson, Jennifer DeWitt, Amy Seakins, and Billy Wong. “‘Science Capital’: A Conceptual, Methodological, and Empirical Argument for Extending Bourdieusian Notions of Capital beyond the Arts.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 52, no. 7 (2015): 922–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21227.

- Barres, Ben A. “Does Gender Matter?” Nature 442, no. 7099 (July 2006): 133–36. https://doi.org/10.1038/442133a.

- Murphy, Timothy F. Gay Science: The Ethics of Sexual Orientation Research. Columbia University Press, 1998.

- Harding, Sandra. “After the Neutrality Ideal: Science, Politics, and ‘Strong Objectivity.’” Social Research 59, no. 3 (1992): 567–87; Harding, Sandra. “Rethinking Standpoint Epistemology: What Is ‘Strong Objectivity?’” The Centennial Review 36, no. 3 (1992): 437–70.

- Benjamin, Ruha. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. 1st edition. Medford, MA: Polity, 2019.

- Science for the People Magazine. “Organize the Lab • Science for the People Magazine.” Accessed May 04, 2023. https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/organize-the-lab/.