Killing in the Name of Precision

The Technoscientific Origins of Drone Warfare

By Hamid Ekbia

Volume 25, no. 3, Killing in the Name Of

Take up the White Man’s burden

The savage wars of peace. — Rudyard Kipling

The use of armed drones has, for the last few years, expanded in military operations by a growing number of countries, putting them squarely at the center of military strategy and policing. A strategy that was developed and perfected early on by Israel and the United States has now spread throughout the globe, with a growing number of countries developing or obtaining drones for foreign and domestic operations. According to reports, more than seventy countries around the globe have developed drone capacity of some sort.

Broadly speaking, the term “drone” can be applied to any airborne vehicle that is remotely operated without a human pilot onboard. Drones, as such, belong to the broader category of technologies called “autonomous vehicles” that are developed for terrestrial or marine navigation as well. Such technologies can be potentially used for non-militaristic purposes such as environmental research, rescue operations, or entertainment. Our focus in this essay is on drones that are used for military or policing operations. The history of such drones can be traced back to different origins, but this essay seeks to highlight the technoscientific origins of drone warfare in cybernetics.

Technically, drone technology has been around for quite a long time, going back to the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, when the very first unmanned airplanes were used as decoys for aerial combat. On May 6, 1896, Samuel Langley, secretary of the Smithsonian, launched a steam-powered drone dubbed the Aerodrome over the Potomac River near Washington, D.C. Although the military application of Aerodrome is not clear, the US Army paid $50,000 for the project in 1898, two years after the early successful attempt.1 In World War I, drones were used as decoys, and in World War II for training of anti-aircraft personnel. Their use was extended to reconnaissance during the Cold War, and to intelligence and surveillance during the Gulf War. It is only in the last two decades when drones have been weaponized with guns, bombs, and missiles.

The US military currently operates a broad range of drones, from nano- and micro- through small tactical and medium-sized all the way to large surveillance and combat drones. The price tag for these drones ranges from $6 thousand to $180 million.2 According to forecasts, by 2029 global spending on military drones will reach $98 billion, with half of it going to large drones.3 Not only does this escalation of drone warfare bring about a set of socio-psychological, political, legal, and moral issues that have been extensively noted by commentators,4 but it is also changing the face of war in ways that seem to lower the threshold for lethal and destructive operations in urban and civilian areas. The most recent example of this is the war in Ukraine, where NATO has supplied the Ukrainian forces with, among other weapons, “kamikaze drones” to be used against the Russian army.5 The Russians, in turn, have started to use Iranian-made drones that have inflicted great damage to urban infrastructures.6

The Geopolitics of Drone Warfare

The appeal of drones to military strategists derives from their greater scope, range, and endurance, as well as their alleged targeting precision. But the other source of appeal is the safety that they provide for remote “pilots,” who engage in combat operations from thousands of miles away. For the first time in the history of war, drones allow the location of their operators to be determined solely based on safety, security, and convenience. Mindful of this unique feature set, military leaders use drones to perform 3D (“dull, dirty, and dangerous”) missions, that is, long-haul flights, reconnaissance operations that require hours and hours of hovering over an area, or combat situations that incur high risk to pilot life. In sum, the idea is that the combination of remote fight and remote flight enables militaries to inflict harm on their enemy without putting their own personnel at risk:7 an asymmetrical war that has given rise to a necro-ethics that allows those with access to technology to decide who can live and who can die.8

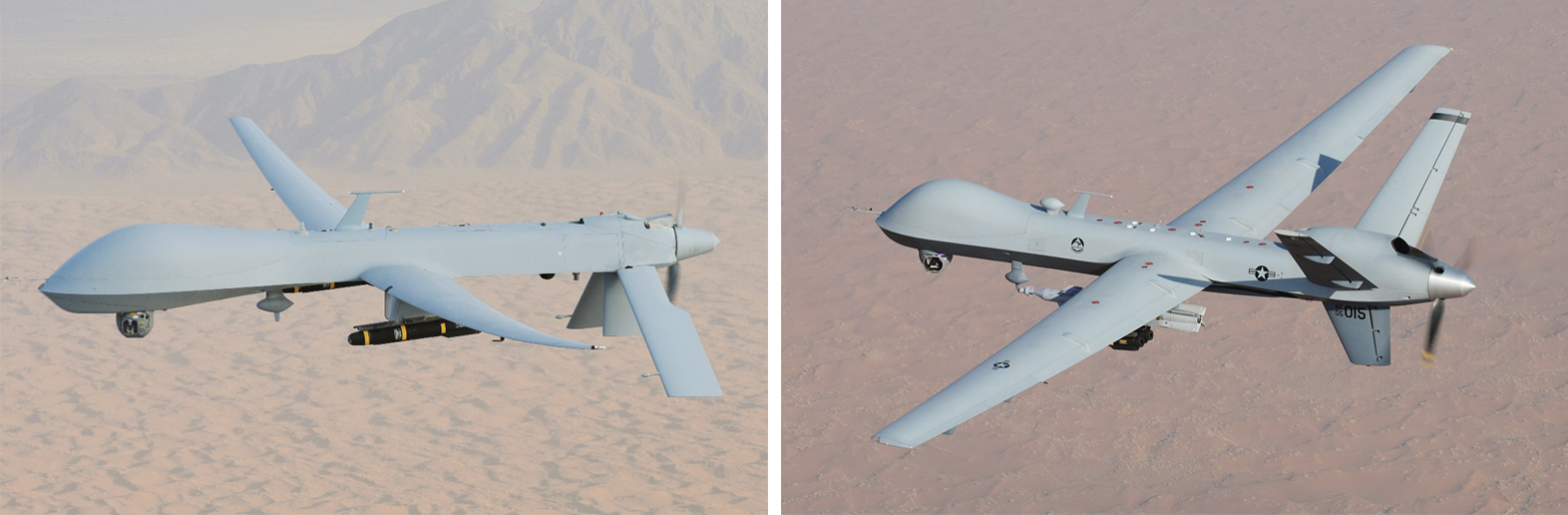

In 2003, when the United States invaded Iraq, only a few drones flew over the region, mostly in support roles for the ground troops. Today, the US military operates thousands of drones ranging in size from very tiny to small airliners. The most common among these are Predators and Reapers that fly over Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia round the clock, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week (Figure 1). Accordingly, the total number of flight hours by drones underwent a ten-fold increase in the years between 1999 and 2009, from almost 20,000 hours to 200,000 hours, and this pace only increased afterwards. In particular, the focus on drones as a key component of counter-insurgency operations by the Obama Administration marked a strategic shift, which was put into high relief by the appointment in 2015 of Ashton Carter, the former head of drone acquisitions at the Department of Defense, as the Secretary of Defense.

There was, to be sure, an element of political calculation in the strategic shift toward drone warfare as a mixture of “soft power and hard power”—that is, of diplomacy and military power, of waging war against a growing insurgency without putting “American lives” in danger. For the Democratic Party, which is often portrayed as “weak” on defense and security in US electoral politics, such a mixture could be expected to provide a desirable “‘tradeoff’ between liberty and security.”9

A Prehistory of Drone Warfare

That political element was also in play a century earlier during the aerial bombings of the 1920s. Seeking to reduce the military budget in the aftermath of World War I, the Lloyd George government of the UK found an ingenious solution in the idea, put forth by Winston Churchill—the secretary of state for air at the time—of an air force integrated into the “imperial police.” It was such that on January 21, 1920, a contingent of six planes were dispatched to bomb the “mad Mullah,” Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, who had led a religious-nationalist insurgency in the Horn of Africa since 1899, describing himself as a mujahid or “holy warrior.” In this way, aviation turned into a strategic weapon of policing in the colonies, justified by the notion of a civilizing justice that divided the globe into two parts: the “civilized” and the “barbaric.” US President Theodore Roosevelt gave voice to this divide in, of all places, his Nobel Prize speech: “There are, of course, states so backward that a civilized community ought not to enter into an arbitration treaty with them”—a racist representation of the world that “brought peace to white people and bombs to the colonized.”10

In a quest for the geopolitical origins of drone warfare, we can go even further back, as the philosopher Grégoire Chamayou has done, finding parallels that connect ancient and modern practices of manhunt, all the way from the hunting of slaves by Romans through the chasing of Indigenous Americans and Black people by European colonists to the surveillance and persecution of foreigners and refugees in our times. The common thread that runs through these practices is to legitimize the treatment of those outside the law as “bipedal cattle” that can be subjected to all manner of exclusion, oppression, and extinction.11 What separates modern practices of manhunt from those of the earlier eras, however, is the use of modern technology brought about by the “Cybernetic Revolution.” It is this distinctive feature that shapes the focus of the present essay, which seeks to show how a seemingly innocuous intellectual project has devolved into a set of ideas and practices that are the polar opposite of its proclaimed intents. A brief exploration of the technoscientific origins of drone warfare unravels some key aspects of the conceptual, moral, and political economies of modern science and technology.

Cybernetics: Control, Feedback, and Prediction

In an ironic twist of history, aerial bombing, which had been established as the strategy of choice for dealing with colonies after World War I, emerged as a decisive element in determining the fate of Europe itself during World War II. The onslaught of Nazi bombers that killed hundreds of civilians in London and other major cities in the UK in 1940 turned the destruction of enemy airplanes into a vital demand of the war. It was in response to this demand that the American mathematician and physicist Norbert Wiener conceived of a calculating device called “antiaircraft (AA) predictor”—a device that would later become the model for a new science known as “cybernetics” after the war. Cybernetics, in the hands of Wiener, was masterfully crafted as a universal science that would not only explain the workings of minds, machines, and matter equally well, but would also provide a philosophical lens for thinking about human affairs—a “Manichean science [that] made an angel of control and a devil of disorder.”12 Weaponized drones, I contend, instantiate both aspects of cybernetics in a faithful manner.

Scientifically, the theoretical foundations of cybernetics were built on technical notions of control, feedback, and servomechanism (a device that uses the errors of a system to correct its action)—notions that were equally applied to living organisms as well as “life-imitating automata” with three general features, which Wiener described as follows:

[T]hey are machines to perform some definite task or tasks, and therefore must possess effector organs (analogous to arms and legs in human beings). . . they must be en rapport with the outer world by sense, such as photoelectric cells and thermometers, which not only tell them what the existing circumstances are, but enable them to record the performance or nonperformance of their own task . . . and central decision organs which determine what the machine is to do next on the basis of information fed back to it, which it stores by means analogous to the memory of a living organism.13

Modern drones—with their “Advanced Precision-Kill Weapons Systems (APKWS),” “Laser-Guided Hellfire Missiles,” “Joint Direct Attack Munition Guided Bombs,” “1,500 pounds of test ordnance,” and “Small Dia Bombs”;14 with their infrared sensors, sophisticated cameras, and zoom-in recorders that capture the carnage in real time; and with their command centers safely located in the Nevada desert six thousand miles away from targeted areas—fit the bill quite accurately, possessing sensors, decision organs, and effectors that tell them what the existing circumstances are, what the appropriate next action is, and whether they have performed their task accordingly—except, of course, when operations go awry, killing children, civilians, innocent passersby, or international aid workers in dozens.15

Philosophically, too, modern drones conveniently map onto the vision of the world and of the enemy woven into cybernetics. Wiener portrayed this enemy in two archetypes who call for different tactics of combat: one as “a contrary force opposed to order,” and the other as “the very absence of order itself.”16 He describes these two types of enemies as follows:

The Manichaean devil is an opponent like any other opponent, who is determined on victory and will use any trick of craftiness or dissimulation to obtain this victory. In particular, he will keep his policy of confusion secret, and if we show any signs of beginning to discover his policy, he will change it in order to keep us in the dark. On the other hand, the Augustinian devil, which is not a power in itself, but the measure of our own weakness, may require our full resources to uncover, but when we have uncovered it, we have in a certain sense exorcised it, and it will not alter its policy on a matter already decided with the mere intention of confounding us further.17

What type of enemy was the target of aerial combat in World War II? Addressing this question head-on, Gallison18 identifies not two but three Enemy Others: the racialized nonhuman enemy, embodied in the Japanese soldiers who “were often thought of as lice, ants, or vermin to be eradicated”; the invisible and anonymous enemy whose humanity, viewed from thirty thousand feet above a German city, “was compromised not by being subhuman, vicious, abnormal, or primitive but by occupying physical and moral distance”; and, lastly but more enduringly, the mechanized enemy “generated in the laboratory-based science wars . . . as a cold-blooded, machinelike opponent.”

“Every single being in Gaza, whether walking on foot, riding a bicycle, steering tok-tok, or driving a car, is a threat to Israel now. We’re all guilty until proven otherwise.”

And what type of enemy, we might ask, is the target of current drone warfare? The answer, it would seem, is all of the above and much more. Listening to the language and rhetoric of contemporary pundits and politicians, we are, on the one hand, dealing with “terrorists who would rather go on killing the innocent than accept the rise of liberty in the heart of the Middle East,”19 with “a terrorist who’s responsible for the murder of thousands of innocent men, women, and children,”20 and with an enemy who “died like a dog, [who] died like a coward.”21 It is hard not to notice the affinities between these descriptions and the three types of Enemy Others described by Gallison as, respectively, nonhuman, remote, and cold-blooded opponents. On the other hand, we witness an increasing willingness on the part of the US government to openly call for the demise of their enemies—whether it is a US-born citizen living abroad, all “men of military age” who are suspected of affiliation with terrorist organizations, or the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi who was wished “captured or killed soon” by then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.22

These attitudes closely echo a decades-long practice implemented by the Israeli government in Gaza and other occupied territories of terrorizing populations who are “unable to sleep due to the ever-present whir of a drone,” not to speak of “a young street vendor who sold sweets, chocolates, and crisps to children and who “became, in the eyes of the drone operator, a valid target, a danger to Israel.”23 Examples like this lead this Gaza resident to conclude, “Every single being in Gaza, whether walking on foot, riding a bicycle, steering tok-tok, or driving a car, is a threat to Israel now. We’re all guilty until proven otherwise.”24

The “disposition matrix,” or “kill list,” created by current cybernetic systems with “predictive analytic” capabilities seems to have not only made the alleged enemy remotely identifiable, it has also lowered the bar for who and what constitutes an enemy.25 In addition to the nonhuman, anonymous, and mechanized Enemy Other, the matrix now envelopes the insurgent, the silenced, and the legally disenfranchised Other. Rather than saving lives, therefore, it has moved the clock back to a new kind of “total war.”

Science: Theory, Morality, and Economy

What does this brief historical survey tell us about the conceptual, moral, and political economy of science? First, at a conceptual level, the original formulation of cybernetics as a science of “control” goes a long way in explaining the devolution of a techno-scientific concept into social practice. Once you formulate a framework that purports to understand everything—machines, animals, and humans—in a one-shot theory, then it is not too hard to get to a totalizing situation where all those entities collapse together in the name of conceptual economy. The road from theoretical hubris to practical peril is hazy, and it is often lined with good intentions. Cybernetics might well be a case where the parsimony principle of Occam’s Razor—that a theory with fewer parameters should be preferred among competing theories—doesn’t work, cutting both ways, so to speak. This is not meant to suggest a linear causality between cybernetic thinking and the rise of drone warfare. For the notion of control predates cybernetics, being ingrained in modern thinking in a deep-seated fashion. What the cybernetic revolution did, however, was to take this modern concept and turn it into the holy grail of science, with Wiener going so far as characterizing our times as the age of information and control.

Similarly, the moral economy of cybernetics—the underlying moral principles that guide its activities26—speaks to a perspective that is heavily invested in a Manichean view of the world and especially of human beings. The case of cybernetics shows how seemingly innocuous, and sometimes even well-intended, ideas developed in the name of science lead to oppressive techniques—a fact that Norbert Wiener himself came to realize in later stages of his career.27 This is not the first time in the modern history of science where an inquiry that was conducted in the name of intellectual curiosity or initiated with a benevolent cause in mind ended up inflicting harm on human societies. From the atomic bomb to behaviorist psychology, and from chemistry to space exploration, modern science and technology presents us with many such examples, turning scientific triumph into tragedy.28 Cybernetics provides yet another such example, where the laudable goal of reducing the casualties of Nazi bombings turned into the opposite in the form of militaristic technologies such as drones. Wiener himself came to realize the danger of this slippery slope from control to enslavement, fearing that scientists might lose “control” over the uses of science. In this light, the point of our earlier comparison between drone warfare and other forms of aerial bombing is not to privilege the latter over the former; they both constitute violent methods of combat, counterinsurgency, and population control. The point is to shed light on a moral foundation that turned science into an ally of destruction and oppression.

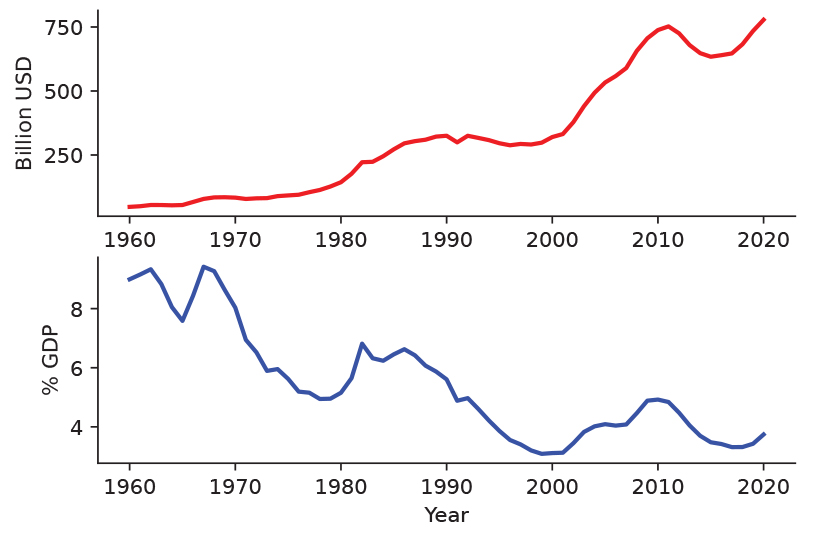

Lastly, drone warfare can tell us a great deal about the political economy of modern technoscience. If drones cannot save lives, as they are often claimed to do, perhaps they can save money—if we listen to some official narratives, that is. Economic figures, however, provide a different story. The Congressional Budget Office, for instance, reports that “UAS [Unmanned Aerial Systems] had both lower acquisition costs and recurring costs per flying hour,” but adds immediately that “They have also been destroyed at a considerably higher rate than manned systems.”29 Comparing the Air Force’s unmanned RQ-4 and the Navy’s manned P-8, the report adds, “On average, each RQ-4’s acquisition cost would be amortized over fewer flying hours than the acquisition cost of each P-8 would be; that difference would more than offset the lower acquisition costs of the RQ-4s.” In layperson’s language, the UAS are more costly in the long run if we take their average lifetime into account. In even simpler language, they are destroyed at a higher rate, wasting taxpayer money at a faster rate than piloted systems (not to speak of the potential environmental damage, which would become a major issue if the current trend were to continue). This might only partly explain the rise in the US military budget in recent years after a temporary dip in mid-2010s—that is, a 14 percent increase in military spending in 2022 compared to 2017, which seems to be also reversing a recent declining trend in the ratio of military budget to overall GDP.30 The bigger point, however, is that economic cost seems to pale in comparison to the political power that it engenders. Drone warfare instantiates the geopolitical aspect of military spending in a vivid manner, because weaponized drones, like other modern weaponry, are not only economically expensive, they also emanate power through their deadly presence.

In summary, the strategists and proponents of drone warfare promised a kind of war that would leave the 3D—“dull, dirty, and dangerous”—aspects of combat to machines. Instead, they have brought us to a point where despair, destruction, and disorder have emerged as the most tangible outcomes. Warnings that observers issued early on about the potential disorder brought about by drone warfare have sadly materialized in a matter of a few years.31 The birds that were unleashed early on into the skies in places such as Afghanistan, Gaza, Pakistan, and Yemen, have come back to roost in unexpected places such as Ukraine and Taiwan—all in the name of precision!

—

Hamid R. Ekbia is Professor and Director of Autonomous Systems Policy Institute at Syracuse University, where he is affiliated with the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs and the School of Information Studies. He is interested in how AI and computing mediate the social, economic, and cultural aspects of modern life.

More articles in Killing in the Name Of will be posted over the next month. Subscribe/purchase this issue to read it today.

Notes

- Stephen L. McFarland, A Concise History of the U.S. Air Force (Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Program, 1997), https://archive.org/details/concisehistoryof0000mcfa/page/2/mode/2up.

- Angelo Young, “Every Combat Drone in Use by the US Military,” November 1, 2022, https://247wallst.com/special-report/2022/11/01/every-combat-drone-used-by-the-u-s-military/.

- Jon Harper, “$98 Billion Expected for Military Drone Market,” National Defense Magazine, January 6, 2020, https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2020/1/6/98-billion-expected-for-military-drone-market.

- Katherine Chandler, Unmanning: How Humans, Machines, and Media Perform Drone Warfare (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2020); Thomas Hippler, Governing from the Skies: A Global History of Aerial Bombing, trans. David Fernbach (New York: Verso, 2017); Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019); Lisa Parks and Caren Kaplan, eds., Life in the Age of Drone Warfare (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

- Young, “Every Combat Drone.”

- Kylie Atwood, “Russia to Build Attack Drones for Ukraine War with the Help of Iran, Intelligence Assessment Says,” CNN, November 21, 2022, https://edition.cnn.com/2022/11/21/politics/russia-iran-drones-intel-assessment/index.html.

- Aki Peritz and Eric Rosebach, Find, Fix, Finish: Inside the Counterterrorism Campaigns that Killed bin Laden and Devastated Al Qaeda (New York: Public Affairs, 2013).

- Grégoire Chamayou, A Theory of the Drone (New York: The New Press, 2015).

- Daniel Klaidman, Kill or Capture: The War on Terror and The Soul of the Obama Presidency (Boston: Mariner Books, 2012).

- Hippler, Governing from the Skies: A Global History of Aerial Bombing, 54.

- Grégoire Chamayou, Manhunts: A Philosophical History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012).

- Peter Gallison, “The Ontology of the Enemy: Norbert Wiener and the Cybernetic Vision,” Critical Inquiry 21, no. 1 (1994): 228–66.

- Norbert Wiener, The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society (London: Free Association Books, 1950/1989).

- Bill Yenne, Birds of Prey: Predators, Reapers and America’s Newest UAVs in Combat (North Branch, MN: Specialty Press, 2010), Appendix A.

- CNN, “US Military Admits it Killed 10 Civilians and Targeted Wrong Vehicle in Kabul Airstrike,” CNN, September 17, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/09/17/politics/kabul-drone-strike-us-military-intl-hnk/index.html.

- Wiener, The Human Use of Human Beings, 34.

- Wiener, The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society, 35.

- Gallison, “The Ontology of the Enemy,” 231.

- The White House, “Remarks by the President on the Capture of Saddam Hussein,” December 14, 2003, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2003/12/20031214-3.html.

- The White House, “Osama Bin Laden Dead,” May 2, 2011, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2011/05/02/osama-bin-laden-dead.

- The White House, “Statement from the President on the Death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi,” October 27, 2019, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/statement-president-death-abu-bakr-al-baghdadi/.

- Shirin Sadeghi, “Hillary Clinton Wants Gaddafi Killed,” Huffington Post, October 19, 2011, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/hillary-clinton-wants-gad_b_1020705.

- Atef Abu Saif, The Drone Eats with Me: A Gaza Diary (Boston: Beacon Press, 2017), 15–16.

- Saif, The Drone Eats with Me.

- Ian Cobain, “Obama’s Secret Kill List: the Disposition Matrix,” Guardian, July 14, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jul/14/obama-secret-kill-list-disposition-matrix.

- E. P. Thompson, “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century,” Past and Present 50 (1970): 76–136.

- Gallison, “The Ontology of the Enemy.”

- Clifford D. Conner, The Tragedy of American Science (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020); Hamid Ekbia, “American Science: Triumph or Tragedy?” Science for the People 23, no. 3 (Winter 2020): 70–72.

- Congressional Budget Office, Usage Patterns and Costs of Unmanned Aerial Systems, 2021, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57260.

- Kyle Bernal, “US Military Budget: How Much Does the US Spend on Defense?” GovConWire, June 1, 2022, https://www.govconwire.com/articles/us-military-budget-2022-how-much-does-the-u-s-spend-on-defense/; see also figure 2.

- Hamid Ekbia, “Technologies of (Dis)Order: Drones, Conflict, and Culture,” lecture, Internationales Forschungszentrum Kulturwissenschaften, March 14, 2016, https://ifk.ac.at/kalender-detail/hamid-ekbia-technologies-of-disorder-drones-conflict-and-culture.html; Hamid Ekbia, “Schöne Neue-Drohnenwelt: Interview with Der Standard,” March 28, 2016, http://derstandard.at/2000033456214/Schoene-neue-Drohnenwelt.