Debt and the Transition to Regenerative Agriculture

By Isaac Bissell

Volume 25, no. 1, The Soil and the Worker

I grew up in a small town in Vermont, and like many I learned to love the smell of fresh cow manure being spread on fields in the spring. Yet, beyond the connection between that smell and the milk on the table, I understood almost nothing about dairy or Vermont’s farm economy. It wasn’t until I started working in the legal department at the Vermont Land Trust (VLT) that I began to understand the way the state’s farm economy actually functions. My role as a paralegal involved managing the legal aspects of conservation easement acquisition projects from the initial drafting of documents through the final acquisition. While I worked on both farm and forest projects, due to my interests, and the region of the state I was assigned to, the majority of the projects I worked on were farmland conservation easements.

Around the time I began working for VLT, I also became intensely interested in soil carbon sequestration as a potential tool to address climate change. The combination of my interest in soil carbon dynamics and my consistent exposure to a variety of large scale farm operations and practices allowed me to probe deeply into our farm economy as it presently exists, and into the barriers that stand in the way of a transition to the alternative methods of production that are capable of helping us adapt to and mitigate climate change. While I came to understand that there are many complex and interconnected issues, two barriers stood out to me as particularly problematic: the consolidation of farmland ownership and debt.

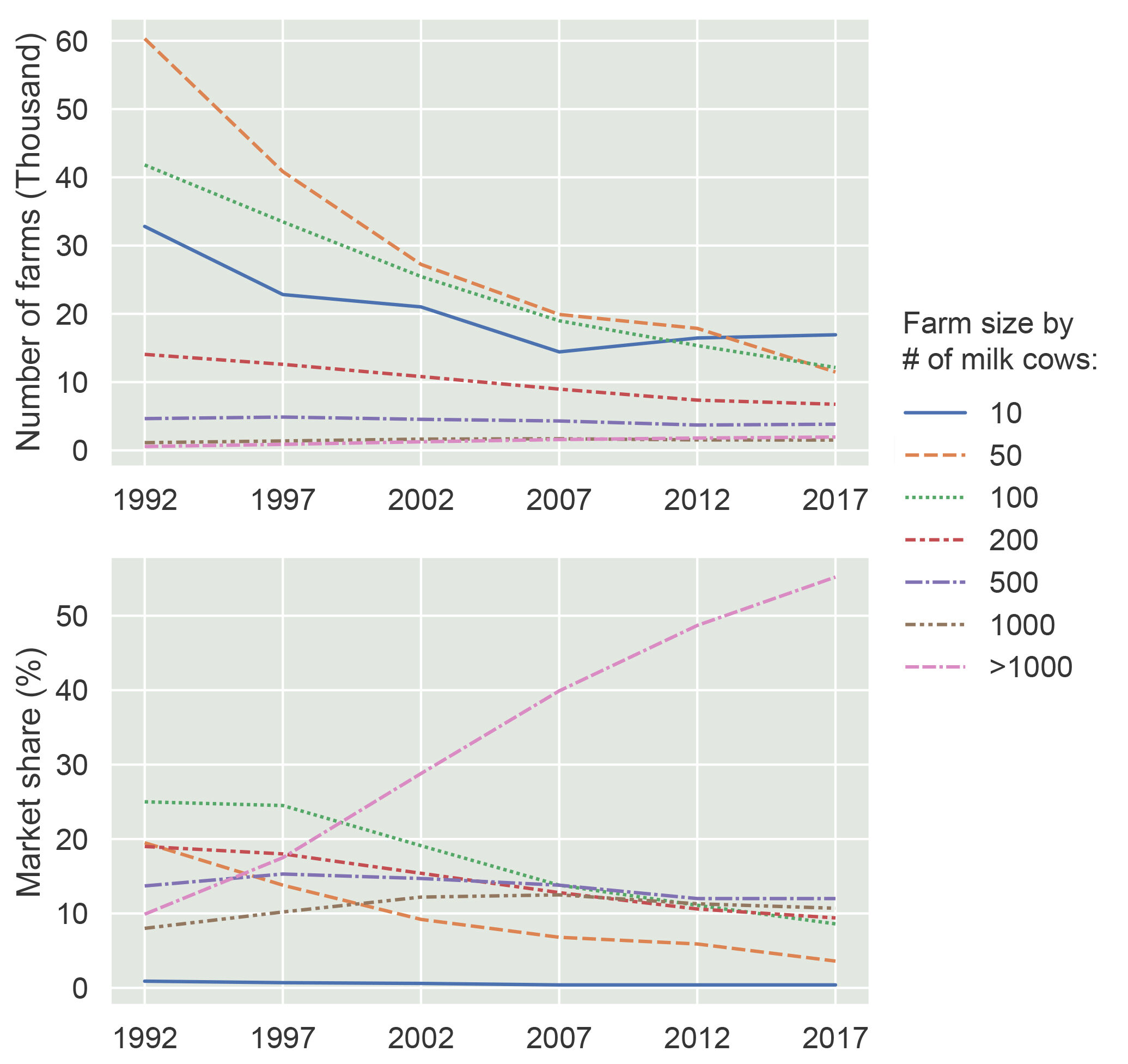

Despite our image as a bucolic state that cares deeply about the environment, Vermont is managing agricultural production in ways that are entirely consistent with federal agricultural policy. As a result, we are dealing with the same economic and environmental issues as the rest of the country. Nationally, we have seen the average farm size more than double from 1940 to 2000, and now almost half of gross farm sales come from farms nearly 3,000 acres in size.1 Vermont’s dairy economy, which presently accounts for the majority of the state’s agricultural production, is therefore oriented towards the large operations that have been able to survive in a competitive agricultural market by growing and achieving economies of scale. While we have seen this loss of small farms, we have seen our largest farms grow dramatically, with the largest dairies in Vermont now operating on around 5,000 acres of land. The total number of dairy farms in Vermont has fallen from around 4,000 farms in the 1970s to only 677 farms by 2020,2 and yet, the total volume of milk production has actually increased.3 Smaller operations have for the most part simply been absorbed into a farm economy that is driven by these extremely large operations. These economies of scale are necessary in order to reduce a farm’s cost of production to the point that it can be profitable.

The need to shift away from a farm economy dominated by the production of one commodity is widely recognized. Opinions about what this shift should consist of vary widely, depending on who you are talking to. The last decade has seen an increasing focus on farm water quality, as phosphorous runoff from dairies has contributed to significant algae blooms in Lake Champlain and other local lakes and ponds. The dairy industry has instituted a number of new practices to reduce their farm runoff. These changes have resulted in water quality improvements on some farms. Lobbyists for the dairy industry state that some conventional dairy farms are meeting their climate obligations by cover cropping annually, by eliminating tillage, by injecting liquid manure instead of applying it on the soil surface, and by using other means to minimize damage to ecosystems.4

Consolidation in Dairy Farming in the United States

Source data: github.com/sftpmag

While there have been measurable and meaningful improvements on certain metrics, the vision advanced by the dairy industry and industrial agricultural lobbyists is not regenerative in any sense of the word. The dairy farms that implement these practices still pollute, they just pollute less. When it comes to the practice of no till, we have seen significant increases in the application of herbicides, as cover crops are terminated annually using an evolving cocktail of chemical herbicides.5 Even if you were to accept the environmental consequences, the simple reality is that an agricultural market dominated by the production of one commodity simply isn’t capable of providing the food security we require.

It is widely recognized that climate change is going to create serious food security issues. Not only is it more difficult to grow food in our increasingly chaotic and unpredictable climate, but our food supply has come to rely on incredibly fragile global distribution systems that will be easily disrupted as our environmental conditions continue to deteriorate. The COVID-19 pandemic has taught us that disruptions to the supply chain can cause shortages at the grocery store that materialize in a matter of days. With climate chaos bearing down on us, we would do well to learn our lesson about the fragility of the just-in-time delivery system and work immediately to produce our food much closer to its point of consumption while using systems of agriculture that are capable of regularly producing in erratic weather patterns.

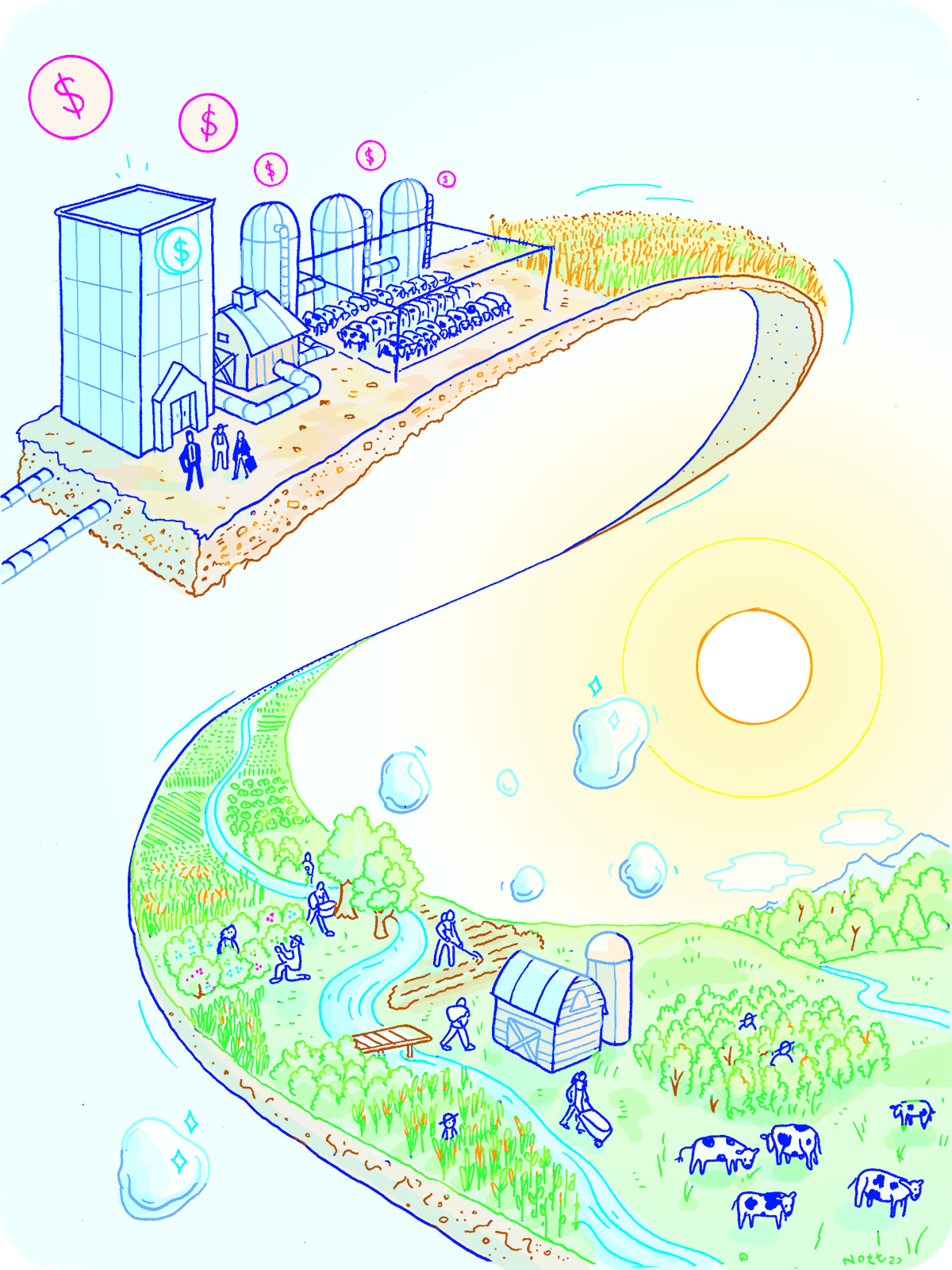

What differentiates the fragile and polluting farm economy we have today from one that regenerates the land while producing a diversity of food in an unstable climate? The fundamental difference between these two farm economies is that one is capital-intensive, while the other is management-intensive.6 A management-intensive operation is one in which the primary asset of the agricultural operation is the observation, engagement and intervention by farm workers.7 A management-intensive operation simply has far more farm worker engagement per acre than a capital-intensive operation. In a capital-intensive operation, the primary assets are capital investments acquired using loans from a bank, which are then utilized to operate at the greatest scale possible using as little labor as possible, with the goal of reducing production costs and maximizing profit through the achievement of economies of scale. Both management- and capital-intensive operations utilize labor and capital to achieve a yield. What differentiates them is the balance between labor and capital.

What a healthy ecosystem demonstrates is that the most efficient means of cycling energy within a system is through a complex network of relationships between mutually beneficial organisms.

Management-intensive farms tend to be smaller, as the importance of human observation and engagement acts as a natural barrier to developing scale. These smaller farms also tend to be more diverse, as crop rotation and the inclusion of animals are prioritized in order to maximize ecosystem health and to reduce inputs. A system of small, management-intensive farms working in a decentralized self-organizing network would mirror the resilience, productivity and diversity of an ecosystem that has been freed from industrial disturbance. What a healthy ecosystem demonstrates is that the most efficient means of cycling energy within a system is through a complex network of relationships between mutually beneficial organisms. It is resilient not just because it is diverse, but because it is a decentralized self-organizing system, wherein portions of the system are capable of functioning on their own should they be severed from the larger network. These are the features that we should be trying to replicate as we design a new agricultural economy. By orienting ourselves towards management-intensive operations, we would be doing just that.

Transitioning to a management-intensive agricultural economy requires us to have much smaller, more diverse farms along with many more farmers. Unfortunately, farmland consolidation has required huge capital investments, which have resulted in extremely large accumulations of debt that ultimately perpetuate the capital-intensive system.8 For the largest operations in Vermont, these debt loads can be well over ten million dollars and have reached the point where shifting away from a conventional dairy operation is not possible under their present economic circumstances. These high debt loads have locked large farms into this specific method of production due to the illiquidity of the assets that the debts are tied to, and due to the inability of alternative methods of production to generate enough net operating income to cover the total debt payments.

An example of one of Vermont’s larger dairies, which went up for sale in 2019, illustrates some problems we face in transitioning our agricultural economy towards a management-intensive approach. This farm, which operates on 3,100 acres, was put on the market for $23 million. Due to the substantial investments in infrastructure and equipment, the farm has its highest value as a dairy, and therefore all of the land, infrastructure, animals and equipment were marketed together.9 There simply wasn’t a way to unbundle this huge capital investment without losses to the bank. Unfortunately, the dairy industry is struggling, and they weren’t able to find a buyer. It remains to be seen how the farm owners will unwind the farm so that they can retire.

Because of the scale of debt and the consolidation of farmland ownership, if we are to shift from capital-intensive agriculture to management-intensive agriculture, the US government will need to provide debt relief that is tied to the breaking up of the largest farm operations. This farmland will need to be redistributed to many smaller management-intensive operations. As management-intensive operations require far more labor, there will need to be a massive retraining program so that workers can learn how to regeneratively manage agricultural soils. We also need to consider the market forces that drove this accumulation of debt in order to make sure that a new agricultural system removes the forces that drive this constant expansion of farms and the associated accumulation of capital. This is a tall order indeed, and it is simply one of the structural shifts that must occur if we are to stabilize the climate before crossing the much discussed but poorly understood tipping points that are likely to result in cascading and unpredictable effects. I wish I had a coherent roadmap to achieving the types of revolutionary changes that are now required, but of course I do not.

What I am suggesting is that any path forward must have a fundamentally radical orientation, and that efforts to achieve incremental change through immediate legislation must be accompanied by organizing that is oriented towards building a movement for more fundamental changes to the structure of our society and economy. We must account for the major economic barriers that stand in the way of the transition that is necessary, and orient ourselves towards efforts that address the underlying causes of the crisis, rather than focusing exclusively on the attempt to mitigate the destructive impacts that result from our capitalist industries. This approach requires that we first analyze the system as it presently exists in order to identify the root causes of the problems that we are facing. The fundamental problem posed by the accumulation of capital, consolidation of land ownership, and the associated debts must be overcome if we are to shift away from an agricultural economy dominated by commodity production.

Notes

- Joe W. Lewis, A New Farm Language: How a Sharecropper’s Son Discovered a World of Talking Plants, Smart Insects, and Natural Solutions (Greely: Acres USA, 2021), 45.

- Lisa Rathke, “Number of Vermont Dairy Farms Drops to an Average of 677,” AP News, January 30, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/f8d70b7f0992a555ec908f7379e2e115.

- Dan D’Ambrosio, “How Vermont Dairy Farms Have Changed: Bigger Herds, More Efficient Production,” Burlington Free Press, May 11, 2021, https://www.burlingtonfreepress.com/story/news/2021/05/11/herd-size-vermont-dairy-farms-getting-bigger-and-more-efficient/5034739001/.

- Marie Audet, “A Revolution to Fight Climate Change is Growing Under Our Feet,” NMPF National Milk Producer’s Federation, accessed April 26, 2022, https://www.nmpf.org/a-revolution-to-fight-climate-change-is-growing-under-our-feet/; Vermont House Committee on Agriculture and Forestry, “House Agriculture and Forestry 01-19-2021-1,” streamed live January 19, 2021 on Zoom, https://youtu.be/AKGbgQP3-ec.

- Daniel Elias, Lixin Wang, and Pierre-Andre Jacinthe, “A Meta-Analysis of Pesticide Loss in Runoff Under Conventional Tillage and No-Till Management,” Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 190, no. 2: 79.

- Claire Kremen, Alistair Iles, and Christopher Bacon, “Diversified Farming Systems: An Agroecological, Systems-based Alternative to Modern Industrial Agriculture,” Ecology and Society 17, no 4 (2012): 44; Liz Carlisle et al., “Transitioning to Sustainable Agriculture Requires Growing and Sustaining an Ecologically Skilled Workforce,” Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 3, no. 96 (November 2019): 1-8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00096.

- In this case, the term “management” isn’t referring to the relationships between farm owners and farm employees, but rather is referring to the intensity of human interactions with the landscape.

- A good example of the type of capital investment that perpetuates our present agricultural economy is the present drive to build manure digesters on dairy farms. The pitch is that by investing in manure digesters we can reduce methane emissions and help with water quality issues, all while generating renewable energy. In addition to fundamental questions about the environmental benefits of this method of energy production, this investment in technology simply represents a doubling down on capital intensive methods of production and will make the transition away from this method of production more difficult in the future. For a recent critique, see Jenny Splitter, “America Has A Manure Problem, and the Miracle Solution Being Touted Isn’t All that it Seems,” The Guardian, Jan 20, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/jan/20/manure-natural-gas-pipeline-factory-farms-greenwashing.

- Molly Walsh, “Big Ag Sale: Is There a Market for a $23 Million Vermont Dairy Farm?,” Seven Days, November 20, 2019, https://www.sevendaysvt.com/vermont/big-ag-sale-is-there-a-market-for-a-23-million-vermont-dairy-farm/Content?oid=28973684.