A Fight to Keep Dumaguete’s Waters Breathing

The Protest of Filipino Scientists and Citizens

By Purple Romero and Raffy Cabristante

Volume 24, no. 3, Cooperation: Theory and Practice for the Commons

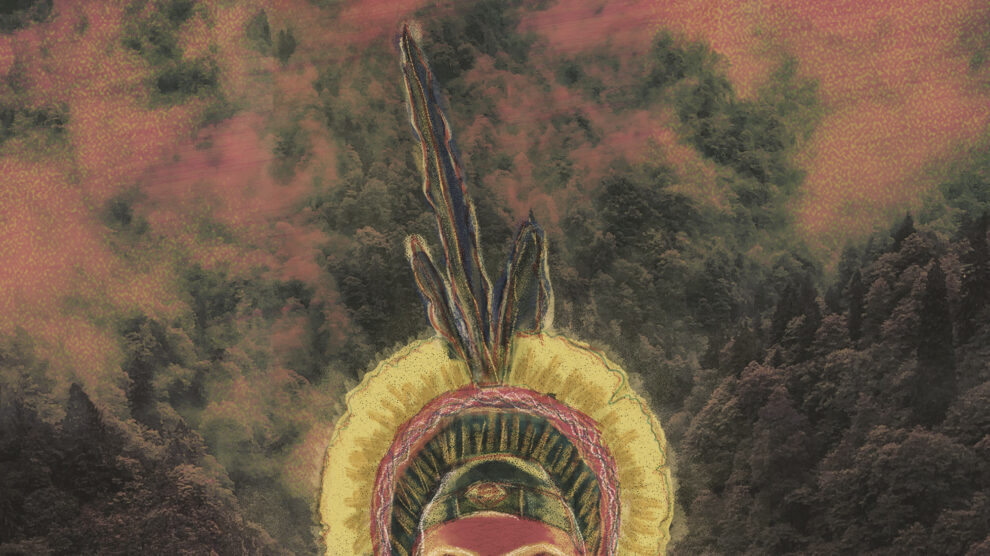

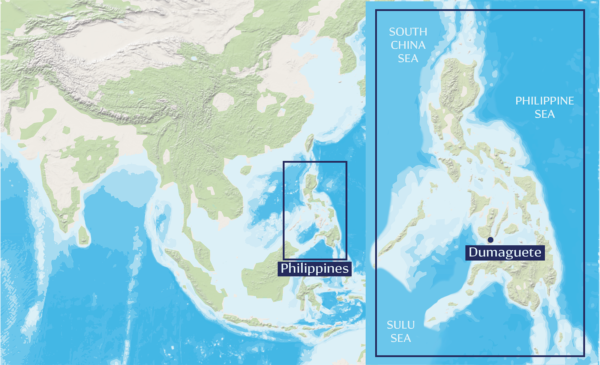

Rene Rafael Juntereal would never forget what he saw that day. The 51-year-old assistant professor and scuba instructor watched as the mayor of Dumaguete, the city where Juntereal lives, denied the existence of the city’s coral reefs on live TV.1 Dumaguete is a coastal city in the Southern province of Negros Oriental, Philippines, well known for its four marine protected areas, including the reefs. To Rene, the denial of the reefs had a purpose: it was to justify construction of a “smart city.”

When shown a video of the reefs, Mayor Felipe Antonio Remollo said in the same interview on ANC, “That is not Dumaguete, I’m sure of it. … It probably must be Apo Island.” He continued, “There are no such corals in Dumaguete; it may mislead the public.”

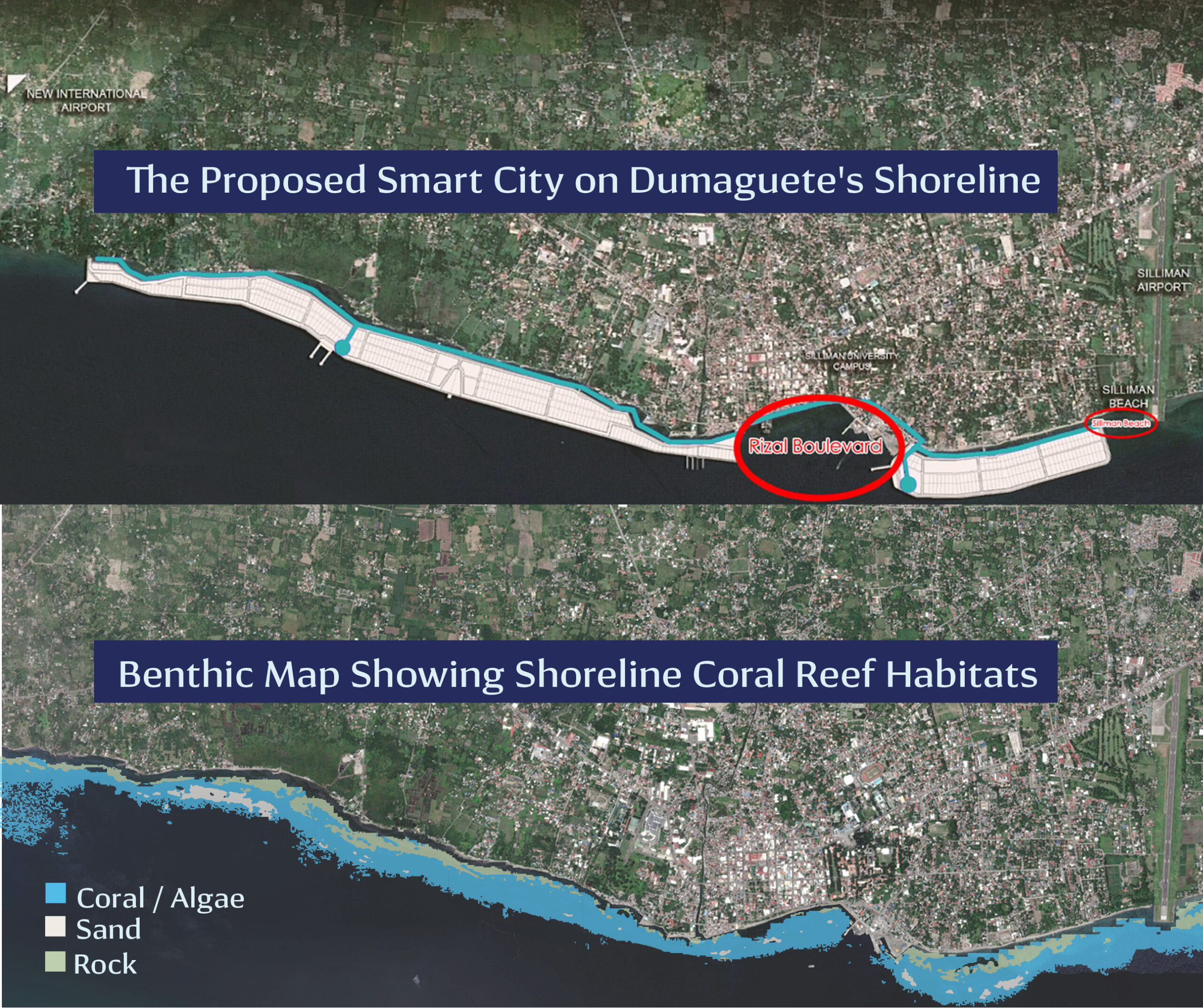

The video was later identified as showing footage of a marine protected area in Bantayan, one of Dumaguete’s villages. Remollo’s assertion came soon after it was revealed that the local government was in talks with the Manila-based construction firm E.M. Cuerpo to lead a 174-hectare reclamation project in Dumaguete. The project is being touted “as a permanent and sustainable solution to our perennial problems of unemployment, brain drain/migration of workers, etc.”2 Included in the project are two wastewater facilities, one of which contains a hybrid solar wind power station.

In a statement addressed to the Dumaguete City Council in August 2021, an E.M. Cuerpo representative said that once the 23-billion peso (PHP; about $453.8 million USD) project goes through, Smart City will bring “more jobs to Dumagueteños during the reclamation and construction of facilities in the project, as well as businesses that will emerge therein.”3 Mayor Remollo initially denied that a memorandum of understanding had been signed with the construction firm, though he later admitted that discussions about the project had started as early as 2019.4

In response to perceived greenwashing by Remollo, Juntereal told the authors in an interview on September 21, 2021, that citizens began work on a community campaign to prove that Dumaguete—contrary to the mayor’s claim—does have coral reefs. Marine scientists joined the campaign to decry their exclusion from the consultation and decision-making process. The scientists pointed out that the project could “bury very large areas of productive coral reefs and seagrass beds.”5

In response to perceived greenwashing by Remollo, Juntereal told the authors in an interview on September 21, 2021, that citizens began work on a community campaign to prove that Dumaguete—contrary to the mayor’s claim—does have coral reefs. Marine scientists joined the campaign to decry their exclusion from the consultation and decision-making process. The scientists pointed out that the project could “bury very large areas of productive coral reefs and seagrass beds.”5

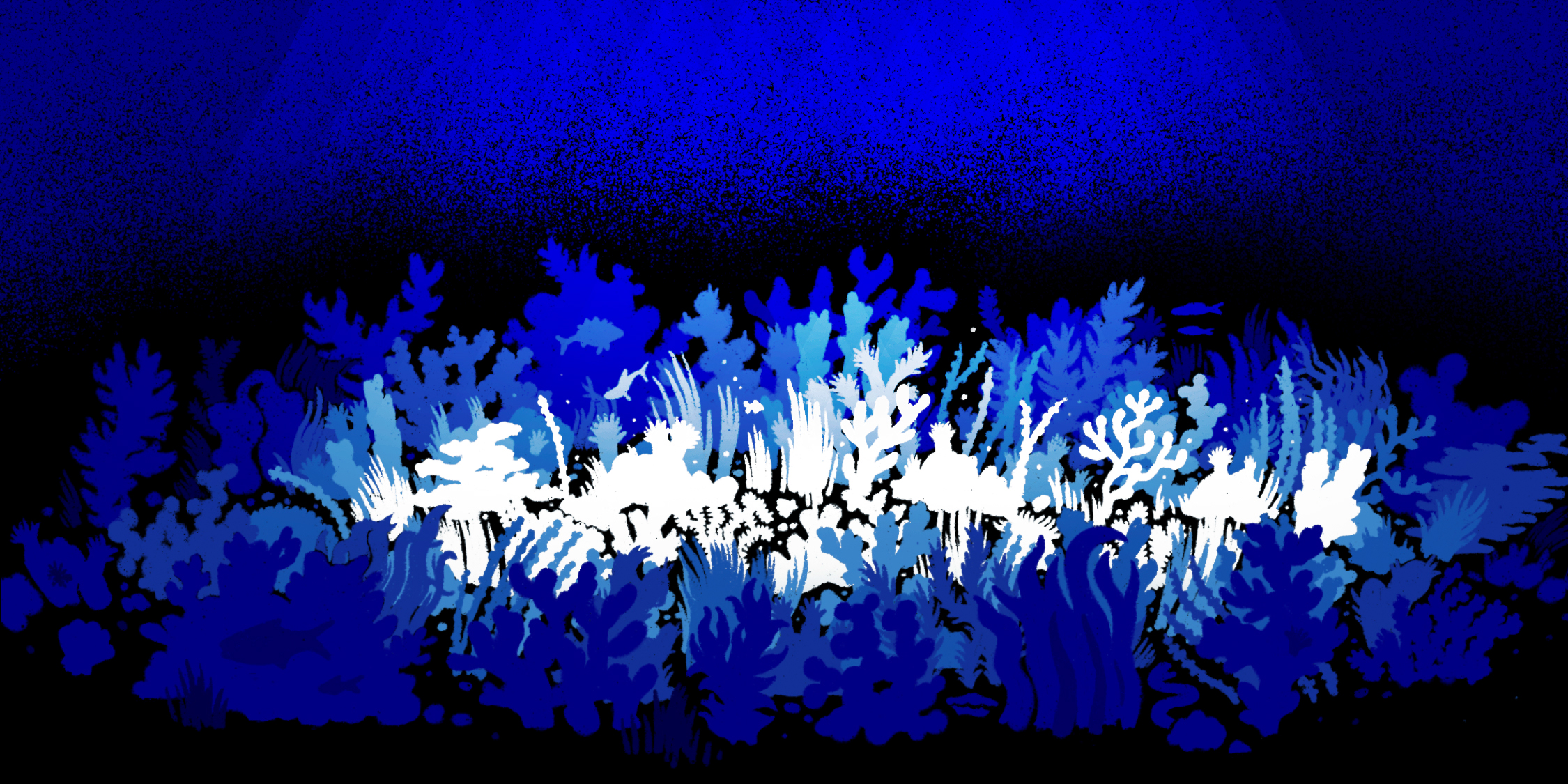

Consequently, the destruction of coral reefs, seagrass, and soft sediments will decimate the livelihoods of fisherfolk in Dumaguete. Indeed, as the current president and two past presidents of Silliman University, a private university based in Dumaguete, pointed out in a joint statement in July 2021, local fisherfolk rely on 60 percent of the fish species found in one of the areas that would be affected by the proposed reclamation.6 The environmental destruction required for Smart City calls into serious question Remollo’s claims that the project would be good for the environment.

Citizen Science Against Misinformation

When Juntereal learned that marine biologists Rene Abesamis and Jeanine Utzurrum, along with the Students Toward Environmental Welfare and Research for Development and Sustainability, were already organizing a campaign to prove that coral reefs could indeed be found in Dumaguete, he jumped at the opportunity to take part in the campaign.7

“I was able to shoot a video, and I posted it on that day,” Juntereal told the authors on September 21. “It was one of the first videos of the Banilad Sanctuary, so it was immediately shared and viewed quite a bit. There were also many others also posting pictures and videos,but mostly of the Escano Area. I must admit that the community involvement in posting all the pictures and videos was pretty amazing and shows how much the community can contribute to efforts like this. The outcome certainly proves that the idea of citizen science can be a truly powerful tool.”

Ramon del Prado, a 39-year-old animator born and raised in Dumaguete, also joined the campaign and posted a video of coral reefs he took on Escano beach, near Silliman University. Del Prado denounced Remollo’s allegations that the coral reefs in the video were shot to mislead the people and that videos like his are “spreaders of fake news.” He hoped that posting a video of reefs he had seen with his own eyes would help expose the mayor’s falsehoods.

Utzurrum, a marine biologist, recognized the importance of mobilizing the whole community, not just scientists, to counter Remollo’s misinformation. “Environmental issues are often multi-sectoral and intersectional,” she told the authors in an email on October 16. “As scientists, we can provide the data; but translating that data into policy or conservation actions requires a foundational understanding of other societal factors (e.g. poverty, waste management, cultural values, power analysis) and help from experts in other fields (i.e. law, finance, social work). Solving these issues should be a collaborative effort.”

Resistance from citizen coalitions has been an effective tool over the past decade in drawing attention to issues that will affect the public. From 2017 through 2020, opposition from residents in Toronto, Canada, proved key in preventing a similar smart city project from gaining ground. And it was the efforts of citizen scientists that demonstrated in 2015 that the water in Flint, Michigan was contaminated with lead and therefore harmful to the health of its residents.8

In Dumaguete, the campaign “rallied the community together and showed that even ordinary people—not just scientists—could go out and see all this marine life thriving and very much alive in our coastal waters,” Utzurrum observed. “Some people were skeptical but most seemed amazed to realize that we have that rich marine diversity so close to our shores.”

Utzurrum said they were already able to collect 65 images and 21 videos of coral reefs in Dumaguete’s waters. This collection of visual evidence became a crucial part of the movement against the reclamation project, which received the name “#Noto174.”

Alongside the campaign mounted by citizens, the 200-member Philippine Association of Marine Science (PAMS) issued a statement on July 24, urging the local government of Dumaguete to “reconsider” the project. PAMS members also called on the Philippine Reclamation Authority, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), and the Department of Interior and Local Government “to treat this project with utmost scrutiny,” and to ensure that the residents of Dumaguete city would be consulted and informed about the possible environmental impacts.

The scientists said that the stakes are high. Dumaguete’s waters, they pointed out, serve as home to “150 species of corals, 200 species of fish, nine species of seagrass, and 20 species of mangroves.” Endangered and protected species such as whale sharks and blue whales can also be found there.

They also reminded the city council that transforming Dumaguete’s marine protected areas into reclaimed land violates laws and defeats the purpose of having marine protected areas in the first place; the main purpose of these areas is to conserve marine biodiversity.

The benthic map was developed using data from the Allen Coral Atlas, a global coral reef habitat mapping project that uses a combination of high resolution satellite imagery, in combination with wave models and other ecological data, to provide reliable and detailed maps for reef-related science and conservation.1 By providing free and publicly accessible data on oceanic ecosystems, the Coral Atlas has important uses in maritime citizen science. The map above, constructed from afar and without intimate knowledge of the landscape, supports the embedded and determined efforts of the Dumaguete citizen science community. When compared with the designs for the proposed Smart City, it becomes blatantly clear that plans of real-estate development do interfere with existing coral ecosystems.—By Nadine Fattaleh |

Misapplying Mitigating Measures

To allay the growing concerns from the public, Remollo asserted that ecosystems could be “rebuilt” elsewhere, with corals relocated and artificial reefs developed.9 However, even the scientists Remollo cited in making this suggestion had some trouble with his proposal.

National Academy of Science and Technology scientist Angel Alcala told the authors in an interview on September 20 that together with Ben Malayang III, the two colleagues were working for DENR in 1995 when it approved an environmental compliance certificate for a reclamation project in the province of Cebu to replace coral reefs with artificial ones. The reclamation project was for the development of South Road Properties, a 30-hectare chunk of reclaimed land now occupied by a mall, a marine theme park, a school, and some condominium buildings.

In July, Alcala, Malayang, and Rene Abesamis on behalf of the National Academy of Science and Technology signed a public statement denouncing the proposed reclamation in Dumaguete.10 They suspect that Remollo’s choice to describe the rebuilding of ecosystems was a disingenuous attempt to “assail the consistency (and implied credibility and moral standing)” of Alcala and Malayang, based on their earlier work with DENR. Although replacing coral reefs with artificial ones made of materials including used rubber tires may have been considered a reasonable approach in 1995 when the proposal they were involved with went through, that is no longer the case. In response to questions from the authors, all three denounced Remollo’s proposal, stating that the methods are “no longer deemed scientifically appropriate.”

Remollo’s “Scientific Approach” is a Load of Hot AIR

Mayor Remollo and the city government made further attempts to use pseudoscience to justify the destruction of reefs in the area around Dumaguete, touting the “Avoid/Integrate/Replace” (AIR) approach as the solution.

“If there are corals or marine life that will be affected,” Remollo said in another TV interview with ONE News, “the first thing I’d do is require the proponent to avoid them. If we cannot avoid the destruction of marine life, step two is to integrate them, which means that [the proponent] must make the design such that marine life would still be preserved by integrating them into the project.”

“If marine life cannot be avoided or integrated, then we will have these affected corals replaced through artificial reefs,” he added, noting that DENR also requires reclamation projects to replace affected marine life with the same quantity of artificial materials.

But Remollo did not specify what technology would be used for these artificial reefs. He has also given no information about the development of the AIR approach and how the city government ended up adopting it as a plan. Several attempts were later made by the authors to reach out to him, but the mayor declined to explain further about his supposed “scientific” approach to the project. Without important details and an actual plan for AIR, scientists are skeptical that these measures will actually work.

“The mayor has advertised his ‘AIR’ concept—‘Avoid/Integrate/Replace Strategy’—as his suggestion of how to avoid destruction of nearshore marine ecosystems,” said Professor Laurie J. Raymundo, director of the marine laboratory at the University of Guam and a former professor at Silliman University, said in an email to the authors. “However, there has been no actual plan proposed regarding how this concept is to be carried out. And, to date, I have heard of no actual budget committed to ensuring environmental damage would be mitigated or avoided.” Raymundo was one of the experts who took part in a series of discussions about the said reclamation project, which was organized by the Rotary Club of Dumaguete on August 22.

In an attempt to get consenting scientific opinion, Remollo also said a marine survey would be conducted from August 14 to August 21 by environmental consultants from the neighboring province of Cebu. A letter of invitation was sent to various stakeholders to take part in the government-backed survey, including the Institute of Environmental and Marine Sciences from Silliman University.11 Matthew Tabilog, a student at the Institute, said they have not heard back from the mayor regarding participation in the survey.

“This survey will then show the value and productivity of the coast of Dumaguete,” Tabilog said in an email to the authors. “The Director of the Institute of Environmental and Marine Sciences from Silliman University gladly accepted the invitation and members from the institute decided to willingly participate in said survey.”

“However, the local scientists and the public were not able to see the environmental consultants doing the survey and it has already been a month since the issuance of the invitation,” he told the authors in an email. “The public are still vigilant regarding this issue and the public even contacted the corporation regarding the survey, but sadly there are no responses from them.”

Following online backlash in response to the survey, particularly by vocal anti-reclamation critic and lawyer Golda Benjamin12, it appears to have been called off, with no further updates from the city government.

“Reclamation-Free” Zones

Meanwhile, the provincial government of Negros Oriental has also expressed concerns over the reclamation project through resolutions and proposed legislation. Last July, the Sangguniang Panlalawigan (Provincial Board)—the province’s lawmaking body—passed a resolution urging the Dumaguete City Council to defer and re-evaluate the authority it gave Remollo to enter into an agreement with E.M. Cuerpo. Quoting a Supreme Court decision in 2015, the Provincial Board said: “As sentient species, we do not lack in the wisdom or sensitivity to realize that we only borrow the resources that we use to survive and to thrive. We are not incapable of mitigating the greed that is slowly causing the demise of our planet.”13

A month later, on August 23, the legislative body passed a proposed ordinance that seeks to ban offshore and foreshore reclamation projects in all 46 marine protected areas (MPA) in Negros Oriental. The proposed ordinance also moved to declare these MPAs “reclamation-free zones.”14

But on September 23, Negros Oriental Governor Roel Degamo vetoed the ordinance, noting that the power to regulate and approve reclamation projects is beyond that of the provincial board. This power, Degamo said, belongs to the Philippine Reclamation Authority (PRA), a national agency under the Office of the President. The provincial board remained adamant, however, overriding Degamo’s veto in a unanimous vote to push the ordinance into law.15

At a Crossroads

For now, the proposed 174-hectare Smart City reclamation is still at a crossroads as residents continue calls for the government to scrap the project altogether. Remollo, while withdrawing his request to the City Council for authorization to enter into an agreement with a contractor on the project, will still continue to apply for the project’s approval from PRA and DENR.

Insider sources from the provincial board said that the ordinance is, to some extent, a move to stall the bid on the reclamation until the May 9, 2022, national and local elections. The reclamation project is expected to be among the major issues that will be tackled in the mayoral race in Dumaguete. Remollo is seeking another three-year term, while his opponent, Board Member Estanislao Alviola, is a co-author of the anti-reclamation ordinance. Because of the clashing stances of both candidates, the Dumaguete mayoral race is also seen as a referendum of sorts on public sentiment.

Alcala, Malayang, and Abesamis urge the local government officials to listen to science. “Science must be deployed,” they said, “to establish the numbers and the facts on the extent and probabilities that these benefits and costs would actually occur,” rather than just accepting hook, line, and sinker the claims made by the project proponents.

Utilizing science to assess projects, they added, has “to be done at all levels of decision making, from local to national,” with the local government officials and the national government working together to assess scientific soundness. A community at large managed to leverage many resources to show the disingenuous nature of Smart City, cutting through most of the damaging rhetoric to arrive at the base facts. It remains to be seen whether the ruling of the Provincial Board will hold, but a strengthening of ties between local scientists and citizens will be key to preventing this latest attempt at a greenwashed land-grab.

This article is part of our Winter 2021 issue: Cooperation. We will gradually post articles online in the coming months. Subscribe or purchase this issue to get full access now.

Notes

- Interview with Mayor Remollo on ANC News, accessed July 17, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/iemsSTEWaRDS/videos/1013101639227835/.

- Dumaguete City, “Proposed Smart City project will promote sustainable economic growth; it will not obstruct the view from the Rizal Boulevard, pier area and Silliman Beach,” accessed July 19, 2021, https://dumaguetecity.gov.ph/2021/07/19/proposed-smart-city-project-will-promote-sustainable-economic-growth-it-will-not-obstruct-the-view-from-the-rizal-boulevard-pier-area-and-silliman-beach/.

- “EMCI Responds to City Council,” accessed August 23, 2021, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1c9W2JQBJsWjz1fIj3OVJyb_CU6LvuWSK/view?usp=sharing.

- “Dumaguete mayor: MOU for reclamation project not yet signed; Premature to judge environmental impact,” produced by ANC 24/7, video, 30:30, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f9Dd3Gtte7o.

- The Philippine Association of Marine Science, “We Oppose the Massive Reclamation Project in Dumaguete,” accessed December 5, 2021, https://pams.ph/philippine-marine-scientists-oppose-dumaguete-reclamation/.

- Rene A. Abesamis et al., “Shore-fish Assemblage Structure in the Central Philippines from Shallow Coral Reefs to the Mesophotic Zone,” Marine Biology 167 (2020): 185, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-020-03797-5.

- Jean Utzurrum, “We launched the #DumagueteCoastIsAlive campaign to show Dumagueteños – esp our City officials – that #corals in Dumaguete are here and not dead.” Twitter, July 17, 2021, https://twitter.com/jean8rum/status/1416411303103537153.

- Mark Peplow, “The Flint Water Crisis: How Citizen Scientists Exposed Poisonous Politics,” Nature, July 6, 2018, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05651-7.

- “Dumaguete Mayor Says They Are Proceeding with ‘Smart City’ in a ‘Scientific Way’,” ONE News, video, 7:27, https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1294104537688169.

- “The National Academy of Science and Technology Statement on the ‘Smart City’ Reclamation Project in Front of Dumaguete City,” accessed December 6, 2021, https://www.nast.ph/index.php/13-news-press-releases/546-the-national-academy-of-science-and-technology-nast-statement-on-the-smart-city-reclamation-project-in-front-of-dumaguete-city.

- Dumaguete City, “Conduct of Marine Survey of Dumaguete City Coastline,” accessed December 6, 2021, https://dumaguetecity.gov.ph/2021/08/16/conduct-of-marine-survey-of-dumaguete-city-coastline/.

- Post from Dumaguete City Government: “LUPAD Dumaguete,” August 14, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/LupadDumaguete2016/posts/1623465597859718.

- NoTo174DumagueteIslands, Facebook, July 12, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/noto174dumaguetereclamation/posts/110307311323720.

- Yes The Best Dumaguete, Facebook, September 2, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/yesthebestdumaguete/posts/4263791153697654.

- Karlowe Brier and Raffy T. Cabristante, “Negros Oriental Board Blocks Projects in Protected Areas,” Philippine Daily Inquirer, September 30, 2021, https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1494902/negros-oriental-board-blocks-projects-in-protected-areas.