Capitalizing on Lockdown While Locking Down on Capital

Imperialism Through the Prism of COVID-19

By Leanne Loo

Volume 24, Number 1, Racial Capitalism

June 28, 2021

Soma makala katika Kiswahili hapa / Read this article in Swahili here.

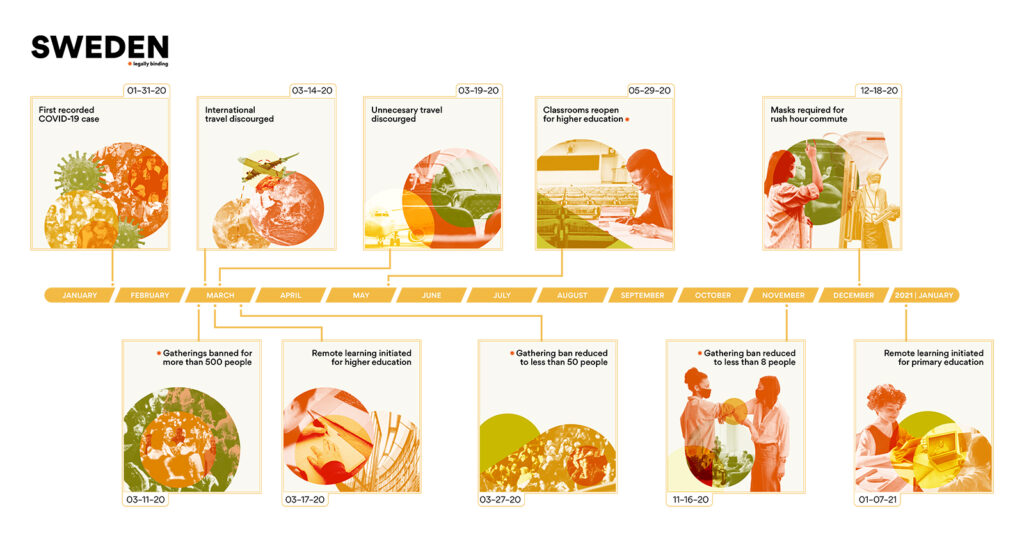

Throughout the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, countries adopted different strategies in managing the overlapping infectious and social implications of the global public health crisis. While many governments and municipalities followed similar measures to varying degrees, such as social distancing, lockdowns, or contact-tracing, Tanzania and Sweden are unique in that they both refused to enforce social distancing guidelines or enact national lockdowns during the first year of the pandemic. Yet, dominant Western narratives tell two markedly different tales.

The international reaction to Tanzania’s relaxed public health measures has been swift and intense since March 2020. President John Magufuli and his administration were criticized by the World Health Organization (WHO), Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, and by numerous public health officials and researchers.1 While criticisms may be justified, what cannot be excused are how Euro-American media narratives and coverage echo the anti-Black trope that portrays Africans as hopeless and incompetent, evoking the exotified and racist stereotype of the savage from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. The Lancet, a prestigious and well-respected medical journal, wrote that Tanzanian healthcare workers were in need of “control compliance” (for example, “to comply with” washing their hands);2 the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the World Peace Foundation called the Tanzanian response “bungled,” “counterintuitive,” and “repressive”; and the New York Times and Foreign Policy reported that Tanzania was “calamitous” and “toxic.”3

It must be noted that these assessments are more suitable in describing the apocalyptic infection and death rates of the United States and various European countries between March 2020 and January 2021. The overt prejudice that Western media and scientists held against African agency was also revealed as African countries “puzzled scientists” in “defying predictions” when millions of Africans did not die of COVID-19 as they foresaw.4

The same patronizing language and tone were largely missing in the narrative of Sweden, which similarly opted to forego lockdowns. In fact, critics afforded far more grace and sympathy to Sweden than Tanzania, with the Swedish hands-off response being characterized as an “enigma,” adopting a “strategy” that would either “succeed or fail,” and ultimately worthy of a debate that evoked “admiration and alarm.”5 Despite signs of failure, Swedish COVID-19 policy was affectionately lauded as the “Swedish model.”6 Framed with scientific ethos, the Swedish model was not to be hastily condemned.

Both Tanzania and Sweden have refused strict COVID-19 measures, yet the media narratives are vastly different. While Western institutions claim to “neutrally” report foreign COVID-19 updates, provide expert commentary and opinions, and research the disease and its epidemiology, they cannot help but reveal their deep-seated racism.

Legacies of European Colonialism in Tanzania

Racist narratives are not spontaneous, nor are they generated out of mere biases; they are results of historical development. As Martinican poet and politician Aimé Césaire said, “no one colonizes innocently.”7 European and North American governments, corporations, and non-governmental organizations are heavily invested in imposing colonial, anti-Black frameworks toward Tanzania, Africa, and the Global South.

Racist narratives are not spontaneous, nor are they generated out of mere biases; they are results of historical development.

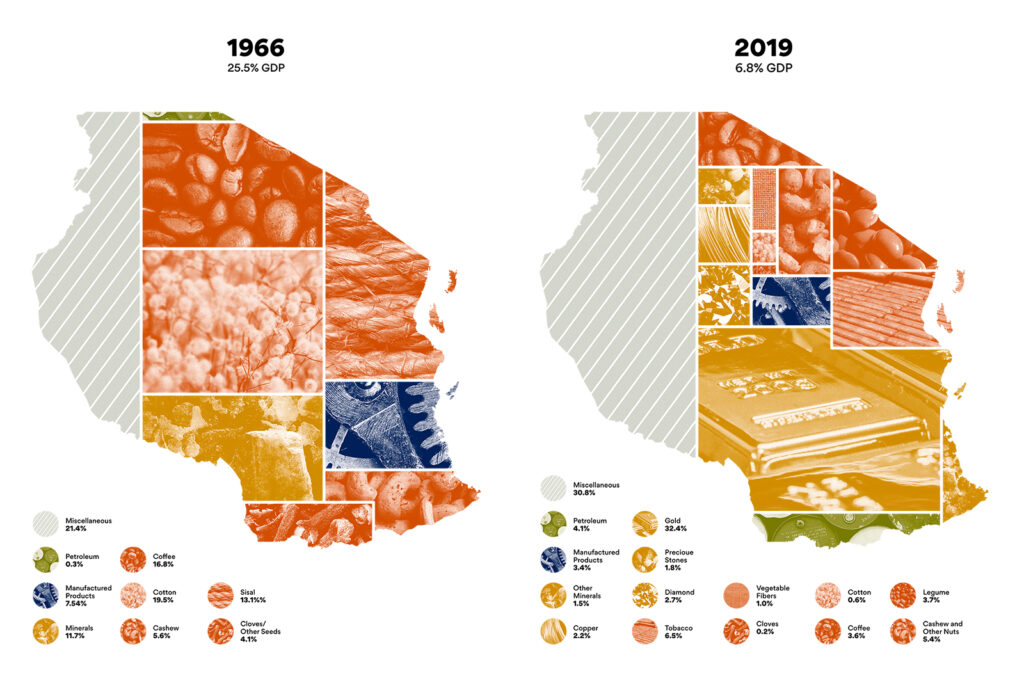

Germany brutally colonized what is now Tanzania under the name of “German East Africa” from 1880 to 1919 to control parts of the slave trade and to plunder the land and resources for their own economic growth; sisal, coffee, rubber, and cotton were forcefully implanted and gold greedily mined. Accumulating capital at the expense of hundreds of thousands of Tanzanian lives, Germany prospered. No irony is lost, then, when Deutsche Welle, a German state-funded media organization, published an article titled “Tanzania’s COVID-19 Denial Risks Pulling Africa Back.”8 Back to what, exactly? Nor is it surprising that another article from Deutsche Welle describes how Tanzanians living in poverty are drawn to “the lure of gold,” risking their lives to gather stones and metal “in the hope of finding small bits of gold amongst the debris,” with no mention of Germany’s key role in starting modern-day gold mining in Tanzania and in impoverishing the country to the point where some Tanzanians feel they “don’t have a choice.”9

When Germany lost the First World War, German East Africa was divided among European victors. Britain took over Tanzania, the majority of which was then known as Tanganyika, from 1916 until 1961. Through institutions already established by Germany’s direct colonial rule, Britain enjoyed the windfall with little investment, maintaining cash-crop plantations for half a century that further entrenched Tanzanian economic dependence on agriculture.

While Tanzanian resources were being subjected to capitalist plunder, Tanzanian people were violently conscripted by Germany to die in the First World War and by Britain in the Second World War. Today, Germany and Britain refuse to pay reparations to Tanzania and other past colonies; they are among many (neo)colonialist nations that actively conceal how colonialism has profoundly structured the world economy to create and maintain the Global North-South hierarchy, with Britain going so far as to burn their archives to destroy some of the most damning evidence of their complicity.10

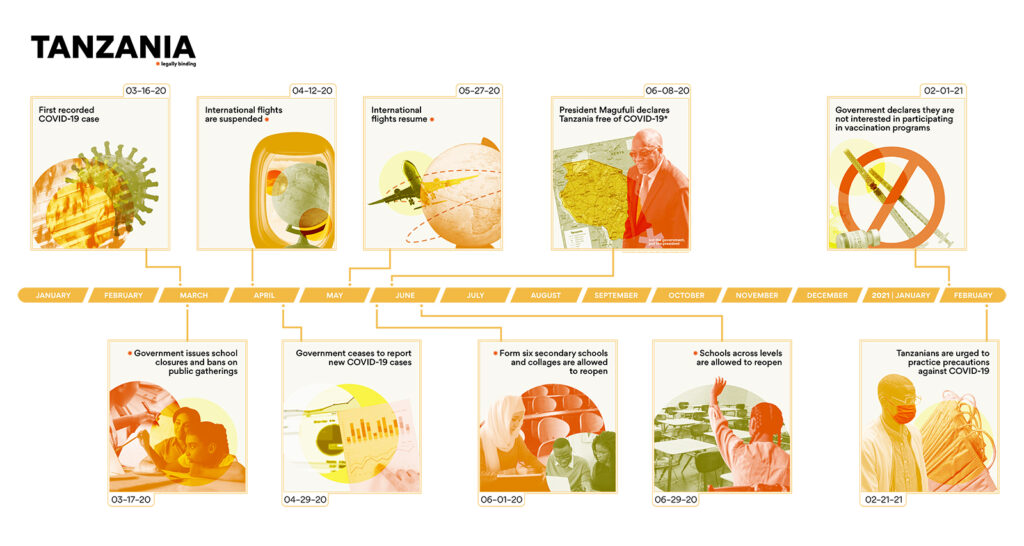

Fig. 1: Comparison of early COVID-19 response timelines between Tanzania and Sweden.

Neocolonialism and Extraction Capitalism

The “essence of neo-colonialism,” explained Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first Prime Minister and President, “is that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside.”11

Today, the industry of gold and diamond extraction in Tanzania continues to flourish since formal colonial rule. Tanzania’s only major diamond producer is Petra Diamonds, a British company.12 Petra Diamonds also owns 75 percent of Williamson Diamond Mines, the largest kimberlite pipe and the first economic diamond pipe outside South Africa,13 while the Tanzanian government owns a meager 25 percent. Similarly, the majority of Tanzania gold mines are operated by another British company, Acacia Mining, under the Canadian Barrick Gold Corporation.

Controlling the vital industries and a large portion of Tanzania’s economy, the West continues its plundering. In 2000, the Tanzanian Ministry of Mines exported $1.7 million worth of diamonds to Belgium.14 The Belgium Ministry of Economic Affairs re-valued the gems to almost seven times as much, $11.5 million, as a result of export price-fixing. As part of a continuing pattern, exports in 2017 from Williams Diamond Mines were severely underreported in their value by Petra Diamonds at $15 million—Tanzania valued the diamonds at $29.5 million. Perhaps a more striking example of robber baronry, the Tanzanian government fined Acacia Mining $190 billion in 2016, which was calculated to be worth two hundred years of the company’s revenue and four times Tanzania’s GDP at the time, for failing to completely disclose its illicit earnings from gold exports over the last two decades.15

In addition to resource extraction, European and North American governments operationalize neoliberal, intergovernmental institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—de facto financial arms of the American empire—to enforce a racialized global hierarchy that oversees the flow of capital from the periphery to Europe and North America. During the pandemic, the World Bank and IMF seized an opportunity to claim the moral high ground by “pausing” Global South countries’ debt payments and offering them “humanitarian aid.” Again, the irony lies with the fact that Global South countries accrued these debts precisely because of World Bank and IMF’s draconian policies—ones designed around the historically brutal imposition of export economies that funneled raw materials to colonial metropoles.

In other words, colonialism persisted despite an end of colonial governance. Before surrendering their colonies, many colonizers’ militaries and civil servants ravaged land and existing infrastructure. France, for instance, burned down schools, farms, hospitals, archives, manuals, and other public goods before departing Guinea in 1958. Newly-independent nations were therefore forced to borrow money from the same colonial masters to repair their countries and provide for their people. The overwhelming economic dependence on raw material and low value-added commodity exports also rendered Global South countries vulnerable to volatile market fluctuations and monopolization. Since the early 1980s, neoliberal structural adjustment programs further tighten the bondage under the whips of Western capital through free trade, austerity, and privatization. Behind their humanitarian façades, the World Bank and IMF have always aimed to re-colonize—to remove the sovereignty and economic freedom of former colonies through financial and military intervention.

Before his assassination in a Western-backed plot in 1980,16 Guyanese scholar and revolutionary Walter Rodney posed a rhetorical question in the beginning of his book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa as to why “many parts of the world that are naturally rich are actually poor and parts that are not so well off in wealth of soil and sun-soil are enjoying the highest standards of living”?17 Rodney went on to answer: “all of the countries named as ‘underdeveloped’ in the world are exploited by others; and the underdevelopment with which the world is now preoccupied is a product of capitalist, imperialist and colonialist exploitation.”

Fig. 2: Legacy of colonialism in Tanzania.

Tanzania was formed in 1964, after the union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar, ending nearly a century of colonial rule from Germany and Britain. However, despite political sovereignty, the Tanzanian economy remained highly dependent on colonial-era cash crop production and low value-added export. This figure compares the composition of Tanzania’s export in 1966 and 2019. In 1966, export constituted 25.5% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP);18 with 53 years of growth, the economy diversified—for example, natural fibers come from more plant harvest than sisal—but still relied largely on agricultural and precious mineral trade.19 Note: The data from 2019 have been simplified to make direct historical comparison: the “miscellaneous” category contains a variety of export items (<2% of total export for each); “manufactured products” contain machinery, clothing apparel, plastic, and glass. Figure outline is of mainland Tanzania, but the statistics shown include Zanzibar and Pemba.

The West, the Other

The reality of imperialism and racial capitalism thus shaped Western mental conception. Philosopher Molefi Kete Asante wrote that “colonization was not just a land issue, it was an issue of colonizing information about the land.”20 Similarly, in Orientalism, Palestinian scholar and activist Edward Said argued that it is not only the physical violence of extraction that comprises imperialism and colonialism, but also the psychological, ontological, and epistemological re-presentation of the Other that structures colonial encounters and relationships.21 The knowledge of the Other constitutes power over the Other, whether that knowledge is true or false. Borrowing from Said, the strategic location and strategic formation of knowledge allow the media to gather mass and referential power, creating an intellectual authority that dominates the Other and justifies this domination.

What COVID-19 offers is a prism through which imperial narratives of disease and contagion rooted in colonial histories are refracted in the present moment.

Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot expanded on Said’s notion of Othering, arguing that the creation of a Savage slot in a broader thematic trilogy of the savage-utopia-order allows the West to continuously reshape a primitive Other to maintain its imperial hegemony; no matter the content in the Savage slot, the primitive Other defined within it is always in subordinate relation to the slots of utopia and order.22 As such, per Édouard Glissant, “the West is not in the West. It is a project, not a place.”23 What COVID-19 offers is a prism through which imperial narratives of disease and contagion rooted in colonial histories are refracted in the present moment. During the pandemic, Tanzania, and Africa more broadly, are re-presented as part of the Other that is perennially backwards, repressive, lazy, and on the brink of catastrophe. Sweden, alongside European and American institutions of knowledge, position themselves as rational intellectual authorities who claim scientific and moral truths that justify the West’s looting of the African continent.

As poet and activist Audre Lorde wrote, “mainstream communication . . . wants racism to be accepted as an immutable given in the fabric of your existence, like evening time or the common cold.”24 The examples of differing narratives surrounding similar COVID-19 prevention measures between Tanzania and Sweden illustrate how imperialist narratives are the keystone in reinforcing a white supremacist, capitalist global hierarchy, for they reify the binary of the superior West and the inferior Other that takes the flow of capital from the Global South to the Global North, from colonized to colonizer, and from Blackness to Whiteness as a natural “logic.” This logic, along with its undergirding imperialism, must be broken for our collective liberation.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Thomas Nyalile for his support throughout writing this piece and his insights into virology and colonialism.

About the Author

Leanne Loo is a student at Tufts University studying Anthropology and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. Her research and organizing are centered in abolition, decolonial feminisms, and transnational solidarity. She is broadly interested in how power operates and how narratives are produced, reproduced, and silenced, with specific attention to imperializing narratives of disease and contagion. Twitter: @leanne_loo

About the Artist

Marina de Haro is a Graphic Designer from Puerto Rico. She focuses on editorial design, branding, and illustration. Her only weakness is bio writing, you can look her up at marinadeharo.com. Instagram: @latardeser

References

- Matshidiso Moeti, “Opening Statement, COVID-19 Press Conference,” WHO Regional Office for Africa, April 23, 2020, https://www.afro.who.int/regional-director/speeches-messages/opening-statement-covid-19-press-conference-23-april-2020; Giulia Paravicini, “Africa Disease Centre Rejects Tanzania’s Allegation That Its Coronavirus Tests Faulty,” Reuters, May 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-tanzania-tests-idUSKBN22J1FO; Sara Jerving, “Muddled Messaging Around COVID-19 Complicates Response in Tanzania,” Devex, July 2020, https://www.devex.com/news/sponsored/muddled-messaging-around-covid-19-complicates-response-in-tanzania-97590; Jaclynn Ashly, “When Coronavirus Came to Tanzania,” The New Humanitarian, March 2020, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2020/03/24/coronavirus-tanzania-africa; Peter Mwai and Christopher Giles, “Coronavirus in Tanzania: What Do We Know?,” BBC News, June 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-52723594; Eoin McSweeney, “Covid Cases Surging in Tanzania, Says US Embassy as Government Downplays Virus,” CNN, February 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/02/11/africa/tanzania-covid-cases-surge-intl/index.html; “Coronavirus in Tanzania: The Country That’s Rejecting the Vaccine,” BBC, February 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55900680; Rael Ombuor and Max Bearak, “Tanzania’s Leader Says His Country Is ‘Covid-Free.’ The Facts Are Proving Him Wrong,” The Washington Post, February 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/tanzania-coronavirus-magufuli/2021/02/17/896e64cc-7123-11eb-8651-6d3091eac63f_story.html.

- The term “control compliance” is derived from the paternalistic term “patient compliance,” which refers to the extent a patient, as an agent, follows medical advice. “Control compliance” is deployed here to describe the degree to which healthcare workers follow biomedical health and safety prevention guidelines. Its usage narratively strips away the agency of healthcare workers, especially those of racialized workers, for they must “comply.” A search for the term in The Lancet, strikingly, only yields two results within the past decade; one article criticizes infection prevention in Tanzania and another questions the quality of health systems in Africa by praising the first article as a “clarion call.” As of March 2021, no articles published by The Lancet in the same period have used “control compliance” to describe European or American healthcare workers.

- Timothy Powell-Jackson et al., “Infection Prevention and Control Compliance in Tanzanian Outpatient Facilities: A Cross-Sectional Study with Implications for the Control of COVID-19,” The Lancet Global Health 8, no. 6 (June 2020): e780–89, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30222-9; Roder-DeWan, Sanam. “Health System Quality in the Time of COVID-19.” The Lancet Global Health 8, no. 6 (June 1, 2020): e738–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30223-0; Judd Devermont and Marielle Harris, “Implications of Tanzania’s Bungled Response to Covid-19,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/implications-tanzanias-bungled-response-covid-19; Ella S. Duncan, “Tanzania’s Layered Covid Denialism,” The World Peace Foundation: Reinventing Peace (blog), September 2020, https://sites.tufts.edu/reinventingpeace/2020/09/11/tanzanias-layered-covid-denialism/; Abdi Latif Dahir, “Tanzania’s President Says Country Is Virus Free. Others Warn of Disaster,” The New York Times, August 2020, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/04/world/africa/tanzanias-coronavirus-president.html; Travis L. Adkins Smith and Jeffrey Smith, “Will COVID-19 Kill Democracy?,” Foreign Policy (blog), September 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/18/will-covid-19-kill-democracy/.

- Alexander Winning, “Puzzled Scientists Seek Reasons behind Africa’s Low Fatality Rates from Pandemic,” Reuters, September 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-africa-mortality-i-idUSKBN26K0AI; Associated Press, “Defying Predictions of Disaster, Africa’s Coronavirus Response Is Receiving Praise,” Los Angeles Times, September 2020, https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-09-22/defying-predictions-africa-coronavirus-response-praised.

- Mariam Claeson and Stefan Hanson, “COVID-19 and the Swedish Enigma,” The Lancet 397, no. 10271 (January 2021): 259–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32750-1; Savage, “Did Sweden’s Coronavirus Strategy Succeed or Fail?,” BBC, July 2020, sec. Europe, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53498133; Gretchen Vogel, “‘It’s Been so, so Surreal.’ Critics of Sweden’s Lax Pandemic Policies Face Fierce Backlash,” Science, October 2020, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/10/it-s-been-so-so-surreal-critics-sweden-s-lax-pandemic-policies-face-fierce-backlash.

- Peter Geoghegan, “Now the Swedish Model Has Failed, It’s Time to Ask Who Was Pushing It,” The Guardian, January 3, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/jan/03/swedish-model-failed-covid-19.

- Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972).

- Chrispin Mwakideu, “Tanzania’s COVID-19 Denial Risks Pulling Africa Back,” Deutsche Welle, September 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/tanzanias-covid-19-denial-risks-pulling-africa-back/a-56501377.

- Julia Hahn, “The Lure of Gold in Tanzania,” Deutsche Welle, December 2012, https://www.dw.com/en/the-lure-of-gold-in-tanzania/a-16527622.

- Ian Cobain, Owen Bowcott, and Richard Norton-Taylor, “Britain Destroyed Records of Colonial Crimes,” The Guardian, April 2012, http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2012/apr/18/britain-destroyed-records-colonial-crimes; Shohei Sato, “‘Operation Legacy’: Britain’s Destruction and Concealment of Colonial Records Worldwide,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 45, no. 4 (July 4, 2017): 697–719, https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2017.1294256.

- Kwame Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism (Panaf, 1974).

- Mark Curtis, New Colonialism: Britain’s Scramble for Africa’s Energy and Mineral Resources (War on Want, 2016).

- A. J. A. Janse, “A History of Diamond Sources in Africa: Part II,” Gems & Gemology, 32, no. 1 (1996): 2–30.

- Ian Smillie, Blood on the Stone: Greed, Corruption and War in the Global Diamond Trade (Anthem Press, 2010).

- Yomi Kazeem, “Tanzania Has Seized a UK Miner’s Diamond Shipment and Spooked the Global Mining World—Again,” Quartz, September 2017, https://qz.com/africa/1074700/tanzania-has-seized-15-million-of-diamonds-from-petra-diamonds/.

- The details behind Rodney’s assassination remain nebulous. The CIA is allegedly involved but evidence is scarce. Asha Rodney, daughter of Walter Rodney, suspected the involvement of “an incredibly repressive, [W]estern-backed regime eliminating and outlawing all forms of dissent.” Devyn Springer, “The Assassination of Walter Rodney.” Groundings. Accessed March 24, 2021. https://groundings.simplecast.com/episodes/the-assassination-of-walter-rodney.

- Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (London: Verso Books, 1972).

- Biersteker, Thomas J. “Self-Reliance in Theory and Practice in Tanzanian Trade Relations.” Africa in Economic Crisis, 1986. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-18371-5_9.

- “What Does Tanzania Export? (2019).” The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://oec.world/en/visualize/tree_map/hs92/export/tza/all/show/2019/.

- Molefi Kete Asante, “An African Origin of Philosophy: Myth or Reality?,” Dr. Molefi Kete Asante, July 2004, http://www.asante.net/articles/26/afrocentricity/.

- In Orientalism, Said argued that the Orient was an “Other” to the West. See Edward W. Said, Orientalism (Vintage Books, 1979).

- Michel-Rolph Trouillot, “Anthropology and the Savage Slot: The Poetics and Politics of Otherness,” in Global Transformations: Anthropology and the Modern World, ed. Michel-Rolph Trouillot (New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2003), 7–28, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-04144-9_2.

- Édouard Glissant, Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays (University of Virginia Press, 1992).

- Audre Lorde, “The Uses of Anger,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 25, no. 1/2 (1997): 278–85.