Hearing Loss in Gaza: Toward A Political Diagnosis

By Raja Sharaf

Volume 23, number 1, Science Under Occupation

Read an Arabic translation of this article online at magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/vol23-1/فقد-السمع-في-غزة-نحو-تشخيص-سياسي-تحرري.

An analysis of any field of medical practice in Gaza is, from the outset, an analysis of thick layers of Israeli oppression. The case I offer here pertains to the field of speech-language pathology and audiology, which was first introduced to Gaza in 1992. In that year, a bachelor’s degree program was offered as a one-time experiment by Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, bringing its professors and practitioners to Gaza to train a group of selected Palestinians. Four years later, in 1996, the first cohort of university-trained speech-language pathologists and audiologists graduated and opened their clinics.

The year 1996 was only three years after the end of the First Palestinian Intifada, which had broken out in 1987. A large number of the patients we—the new graduates—received were adolescents and young adults who had been beaten by Israeli soldiers in demonstrations and during interrogations in Israeli jails. These young men and women described being repeatedly hit on the head and receiving direct blows to the mastoid bone, which caused irreparable damage to the auditory nerve. Blows to the head and ear had also caused perforation to the eardrum and damaged the ossicles in the middle ear. Severe beating was an official Israeli policy to quell the intifada. Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s Minister of Defense at the time, termed this policy “force, might, and beatings.” Many of those who suffered beatings went completely deaf.

Those who did not go completely deaf had to be provided with hearing aids, which at the time cost about $300 US. This was not cheap, given the economic situation of most Palestinians at the time. In the 1990s, Israel gradually reduced its dependence on Palestinian labor, forcing tens of thousands out of employment, due to workers’ participation in the intifada and in labor unions.1 Despite these restrictions, many managed to collect donations or relied on their savings from working in the Israeli construction sector in the 1970s.

Providing hearing aids, however, does not do much without a supportive social environment. In the 1990s, speech-language pathology and audiology was still a nascent field. This meant that the mitigation of hearing loss was primarily a medical—rather than social—practice, limited to clinics. The broader society often did not know how to communicate with hearing-impaired relatives and friends, who found themselves ostracized from society. To address this problem, we organized home visits to teach sign language to family members and to provide advice on how to foster a supportive environment for the affected individuals. Today, Gaza has specialized centers and schools for hearing-impaired children, as well as clubs and a limited number of university-level programs. Sign language has also been integrated into some television programs.

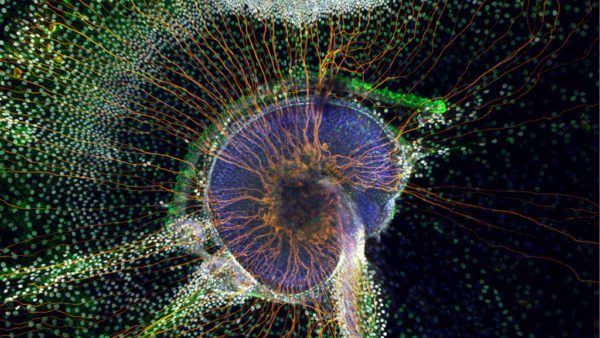

Despite these improvements, hearing loss has remained a significant and growing problem since the imposition of the Israeli siege in 2007. Large-scale Israeli bombing and sonic-boom air raids have led to an increasing number of Palestinians who suffer from sensorineural hearing loss. This condition arises when the sensory receptors are exposed to loud noises, which cause them to bend and stop working. There are no authoritative statistics to indicate the proportion of hearing loss inflicted by Israeli violence. This is partly because statistics are usually not sensitive to history, which makes it difficult for statisticians to link something like hearing loss directly to Israeli violence. Unless the injury is visible, as with shrapnel wounds, or when hearing loss occurs directly after an airstrike, the correlation is not accounted for. As practitioners, however, case history is crucial to our understanding of bland numbers and hard medical diagnoses and is indispensable to treatment, which almost always involves psychotherapy. The geographic distribution of Israeli-inflicted hearing loss is also very telling: throughout my medical work, it has been very difficult to pin these cases to specific areas. The scale of Israeli violence is all-encompassing, such that it is impossible to know through medical observation which areas in Gaza are targeted more than others.

This violent attack on Palestinian health is further complicated by Israel’s systematic destruction of our healthcare system and of our ability as medical practitioners to do what we know is best for our patients. Today, the price of hearing-aid equipment in Gaza ranges between US $400 and $1,000, depending on the technology and quality of the device. In Gaza, almost half of the population is unemployed, and even those who do have some form of revenue cannot afford to pay such exorbitant prices.2 The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) has a program focused on conducting preliminary hearing screenings for children in schools and providing them with hearing aids. Yet, the process is highly selective and often leaves the majority of those hard of hearing without the treatment they desperately need. UNRWA and many other organizations such as the Islamic Relief often do not have sufficient funding to provide hearing aids for everyone identified. An excruciating selection process follows, whereby those identified are transferred to us for a detailed hearing test. Based on this test, we have to help determine which patients need hearing aids more urgently than others. Age and degree of language acquisition are important determining factors. If we have to choose between an adult and a child, hearing aids most likely go to the latter because of how crucial hearing is to the early development of language and social skills. Yet, once selected, a child who needs hearing aids for both ears might end up with only one, so that another child might also benefit. As a result, many hearing-impaired children with a full capacity to be socially and linguistically competent ultimately instead deteriorate.

Israel also imposes severe restrictions on hearing aids, most of which are delivered to us through Erez Crossing, a large Israeli military checkpoint north of Gaza. In my clinic, we often face months of delay while Israel conducts “security checks” on the equipment (including earmolds and spare parts), and as Israelis celebrate national and Jewish holidays. These delays are detrimental to patients, who are often thrown into open-ended waiting and a daily struggle in overcrowded classrooms and busy workplaces, where constant exposure to unfiltered noise causes further hearing deterioration, anxiety, and social isolation.3

Less discussed than all this is the social stratification exacerbated by the access of some to better hearing aids than others. Most hearing-impaired people in Gaza with access to hearing aids wear the lower cost, Behind-the-Ear (BTE) technology. Because they are visible, these hearing aids are very difficult for adolescents, who feel too embarrassed to wear them or risk bullying at school, to accept. In contrast, those who can afford more expensive equipment buy the small and invisible Completely-in-Canal (CIC) hearing aids. This differentiation, which to adolescents is very significant and affects their self-confidence, contributes to the simmering class tensions and decomposition of social solidarity already unfolding in Gaza as a matter of Israeli policy.4

There are also cases of divorce precipitated by hearing loss and the inability of one or both married individuals to overcome the challenges and changes that come with it, including the loss of income. The service sector in Gaza employs a majority of young people who have just started a family or are preparing for one. Especially in customer service, and in the absence of strict labor laws, many are dismissed after an airstrike, bullet swoosh, shrapnel, or some other cause destroys their hearing. The private sector, such as telecommunications, has also recently begun to demand hearing test results as part of the job application. While there are no statistical figures on the relationship between hearing disability and employment, patients who talk to us during their visits tell stories of how they were fired after having been found to “mishandle” a phone call or conversation with a customer.

In clinics, we often work under severe strain. We repeatedly find ourselves unable to provide our patients with the hearing aids they require, due to the lack of funds or equipment. We also have no access to new learning opportunities in the field. We cannot travel to attend conferences, cannot acquire recent books and publications, and do not have state-of-the-art laboratories or tools. These difficulties are compounded as we have to straddle multiple professional roles beyond our immediate field, primarily in psychotherapy. A significant number of our patients are children who, having suffered shock and intense fear after an Israeli airstrike or invasion of their neighborhood, develop speech disorders such as stuttering. In these cases, the best approach is what we call “team therapy.” Team therapy usually involves close collaboration among speech-language pathologists, psychotherapists, educators, and parents. Yet, psychotherapy and education, much like speech-language pathology, operate in a difficult environment with very little support. These circumstances make collaboration between different fields very challenging and hard to manage. As such, we in speech-language pathology often find ourselves acting as psychotherapists and end up spending long sessions with parents to discuss how to best support their children. We also sit with the children themselves to provide them with emotional support at the same time as we help them move through the speech therapy plans and goals.

We do learn a lot in the process. Our most crucial lesson has been that hearing disability is not an apolitical medical condition whose solution simply lies in hearing aids, economic prowess, and social support. Hearing disability and the destruction of the healthcare system are part of Israel’s systematic oppression of the Palestinians. The humanitarian language of “development” and “improvement” does not work. Nor do NGO-type projects work in the long run. A functioning healthcare system requires the systematic dismantling of and fight against Israeli settler-colonialism and its structures of oppression. Any discussion of any medical field in Palestine must take into consideration these very structures.

About the Author

Raja Sharaf is an audiologist and speech-language pathologist from Gaza, Palestine. She graduated in 1996 and has been working in the field for twenty years.

References

- Yezid Sayigh, Armed Struggle and the Search for State: The Palestinian National Movement 1949-1993 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- Megan O’Toole, “Gaza 2020: Has the Palestinian Territory Reached the Point of no Return?” Middle East Eye, December 9, 2019.

- Maha Hussaini and Nada Nabil, “Gaza 2020: Our Worst Nightmare is When It Starts Raining,” Middle East Eye, December 10, 2019.

- Rana Baker, “Return to What? Against Misreadings of Gaza’s Great March,” Mada Masr, October 14, 2019.