June 30, 2021

What Can a 1998 Lawsuit Teach Us About Vaccine Inequality Today?

By Jacklin Kwan

We find ourselves in the midst of an unwelcome but, unfortunately, all-too-familiar power struggle resulting from the current global COVID-19 pandemic. While people worldwide have denounced the failures of their respective governments to respond to the pandemic, which has led to millions of preventable deaths, it is the moral failings of Western countries that have been particularly egregious. A coalition of richer states in the World Trade Organization (WTO), including the United Kingdom and the European Union (and formerly the United States), is blocking a proposal backed by more than a hundred developing nations that would allow manufacturers to make generic vaccines and enable countries to produce and distribute life-saving injections.1

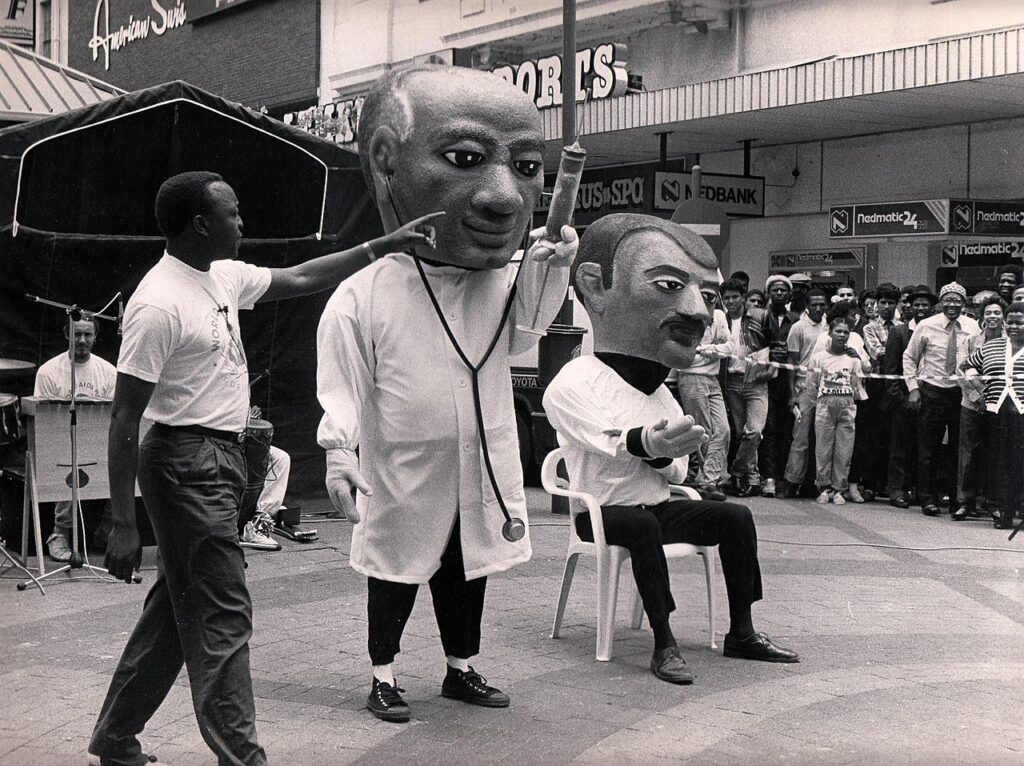

While richer countries began vaccination programs in late 2020, the global poor are forced to wait as the coronavirus continues to take untold millions of lives.2 This injustice, however, is nothing new, and the arguments being used to restrict access to life-saving healthcare are neither novel nor sound. In South Africa, a nation advocating for waiving intellectual property (IP) rights to the COVID-19 vaccine, these exclusionary tactics may seem eerily familiar. In 1998, as sub-Saharan Africa was being ravaged by the global HIV/AIDS epidemic, South Africa sought to make HIV antiretroviral medication affordable to its population. The result? More than forty pharmaceutical corporations took the country to court in the now-landmark ‘Pharma’ v. Mandela lawsuit.

Revisiting this 1998 lawsuit now provides the opportunity to dissect the justifications presented by the pharmaceutical industry to maintain its iron grip on its patents at the expense of human lives. The case lays bare the incentives of pharmaceutical lobbyists and politicians with financial interests in these patents. It also charts a pathway to victory.

HIV Becomes a Sub-Saharan Epidemic

It is 1997 in South Africa, just fifteen years after the first domestic AIDS cases were reported. The prevalence of HIV among adults is up to 12.9 percent, having risen exponentially since 1990.3 Though other countries in Africa face spiraling infection rates, South Africa is one of the worst affected; it has the highest absolute number of people living with HIV/AIDS. And while a fifth of the population is covered by private healthcare, the rest rely on overstretched public resources.4

Three years earlier, the Minister of Health, Dr. Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, had appointed a National Drug Policy Committee to investigate the deficiencies in South Africa’s healthcare system and identify ways to address them.5 One of the committee’s principal findings was that essential drugs, including HIV antiretrovirals, were inaccessible to South Africa’s population, largely due to affordability. The mean monthly income of South Africans in 1997 was around $220, while the monthly cost of HIV antiretroviral drugs was $1,000.6 Half of the population lived in poverty and 31 percent were unemployed, most of whom were Black.7 In consideration of all of these factors, the committee recommended a three-pronged response: lowering drug prices; supporting the development of a local pharmaceutical industry; and promoting the prescription of generic drugs across both public and private sectors.

Governments typically lower the prices of expensive drugs—without waiving IP rights—by adopting one of two strategies. The first strategy is compulsory licensing. This allows a company to produce a drug protected under another party’s patent without the rights holder’s consent, in exchange for a small fee. Under this model, the company producing the drug does not have to be local or necessarily affiliated with the government that issues the compulsory license. This strategy was adopted, for instance, by the Brazilian government in 2007 to allow the import of generic versions of the antiretroviral efavirenz after the medication’s patent holder, Merck & Co., did not meet the requested 60 percent price reduction. The generic drug was imported from companies in India to Brazil, saving upwards of $237 million between 2007 and 2012.8

The second strategy governments use is parallel importation, whereby unlicensed distributors import drugs from another country without the rights holder’s consent and sell them for less than the retail price. Within the European Union, it is permissible for a firm to purchase large quantities of prescription drugs in Spain, then export them to Sweden or Germany without the approval of the distributor that owns the patent rights. This practice is even encouraged by local health insurance companies to promote lower drug costs. These strategies of compulsory licensing and parallel importation do not completely void IP rights, but they do weaken some of the associated monopoly powers that enforce price control.

In December 1997, President Nelson Mandela ratified the new Section 15C of the South African Medicines and Regulated Substances Control Act (MRSCA), explicitly allowing parallel imports of patented drugs in order to lower drug prices.9 As a result of this modest proposal, South Africa found itself the target of an international lawsuit. More than forty pharmaceutical companies attempted to block the 15C amendment, challenging its constitutionality before the High Court of South Africa. The legal challenge asserted that South Africa had violated the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) and had, thus, also violated the South African Constitution.10

South Africa was now in the center of one of history’s largest IP disputes. Concurrent with the legal proceedings in South Africa, US diplomats, including then-Vice President Al Gore, increased international political pressure on South Africa, urging the state to drop the MRSCA amendment.11 The US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright acceded to a request by Congressmen Robert Menendez and Edward Royce to place South Africa on the US Trade Representative’s Special 301 Report watchlist. The watchlist consists of countries deemed to have inadequate IP laws.12 Countries on the watchlist may be brought into WTO dispute proceedings and may face unilateral trade sanctions by the US.

TRIPS: A Long History of the Right to Property

In order to understand the strength of the pharmaceutical lobby, both in the late 1990s and now, it is important to look at how the industry created and justified its mission. How were structures like TRIPS even possible, when they clearly compromised universal access to healthcare?

In the decades leading up to the ‘Pharma’ v. Mandela lawsuit, IP owners lobbied vigorously for property protection laws, culminating in the victory that was TRIPS in 1989 and 1990. TRIPS requires all WTO member states to provide strong protection for IP rights, including ensuring ending copyright terms last for at least fifty years and the adoption of standardized enforcement and dispute mediation procedures.13 These robust frameworks reflect the close influence that pharmaceutical industry representatives had on the negotiation processes. They established financial links to US diplomats, resulting in a revolving door approach among the US Patent and Trademark Office, governing boards, and drug manufacturers.14 Pharmaceutical industry representatives were particularly aggressive in persuading US policymakers to enforce strong IP standards in developing nations.

Alongside attempts to directly co-opt US policymakers, pharmaceutical lobbyists advanced a few key arguments (which readers may recognize). The first was self-victimization. Clayton K. Yeutter, the US Trade Representative in the late 1980s, testified before Congress in 1996: “[American firms] must rely on foreign governments to protect their valuable intellectual property rights. Often, foreign governments fall short, leaving US owners of intellectual property defenseless against piracy.”15 His language frames IP rights holders as “defenseless” against foreign pirates threatening to purloin American innovations. Suddenly, some of the wealthiest companies in the world were cast as victims of moral violation, in need of protection.

The second argument explicitly advanced by the pharmaceutical industry was outlined by Gerald J. Mossinghoff, the head of major US pharmaceutical lobbying group PhRMA. In a 1996 Senate hearing, Mossinghoff blamed the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act, a US federal law that encourages the manufacture of generic drugs, for weakening incentives to develop life-saving medication: “Sustained innovation is really our only hope for reducing [the toll of life-threatening diseases such as AIDS],” he argued. “But because Hatch-Waxman, combined with a far tougher marketplace, has dampened the incentives for R&D [research and development] investment significantly over the past 11 years, there is a danger that less innovation will occur in the future.”16 Mossingoff implies that the pharmaceutical industry is moral in nature, but requires market incentives to pursue its ultimate goal of providing essential medicines to the developing world.

This position, though theoretically possible, was not grounded in reality. Developing countries contributed only 20 percent of global pharmaceutical sales in 1998, despite comprising 85 percent of the world’s population.17 Most drugs were targeted towards consumers in richer countries and the wealthy urban classes of developing countries. In fact, between 1975 and 1997, only sixteen drugs for tropical diseases and tuberculosis reached the market out of the 1,393 drugs marketed around the world.18 Drug industry analysts argued that the industry, rather than trying to avert a loss of profits, was actually attempting to preserve its control of the global market.19 The creation and marketing of generic drugs could have forced pharmaceutical companies to reevaluate their pricing structures. To avoid admitting they wanted to charge higher prices for medications, pharmaceutical companies positioned themselves as victims of piracy and as moral pioneers of high-risk R&D.

Victory Comes in the New Millennium

Significantly, the ‘Pharma’ v. Mandela lawsuit was in progress during the lead-up to the 2000 US Presidential Election. Former Vice President Al Gore, who was running for President, was also intimately connected to the litigation effort in South Africa as co-chairman of the US-South African Binational Committee. AIDS activist groups, such as ACT-UP and AIDS Drugs for Africa, seized the opportunity to pressure Gore to change the US position on the lawsuit by leveraging his vulnerability to negative publicity on the campaign trail. A number of his campaign events were interrupted by activists shouting, “Gore’s greed kills”.20 Throughout the summer of 1999, Gore’s financial links to the pharmaceutical industry also came to light.21

By September, AIDS activists had won two major concessions. The US government announced that it would no longer pressure South Africa, as long as South Africa swore to adhere to its TRIPS obligations. South Africa was removed from the Special 301 Report watchlist, and the plaintiffs of the anti-MRSCA lawsuit temporarily suspended their case.22 In May 2000, US President Bill Clinton signed an executive order avowing that the United States would no longer engage in unilateral negotiations to pressure countries on their legal response to AIDS. PhRMA lobbyists expressed intense disapproval, stating that the order would set a negative precedent for international IP rights protection.23 Pharmaceutical companies stressed that UN-mediated negotiations had reaffirmed South Africa’s responsibility to protect patents, but it was clear to activists that these companies were going to lose.

In 2001, the newly inaugurated Bush administration reaffirmed Clinton’s non-interventionist stance, and by April, pharmaceutical companies were forced to drop their legal challenge of Section 15C and cover South Africa’s legal expenses.24 The associated publicity catastrophe had earned the pharmaceutical industry a bad reputation. And when the MRSCA was modified again in 2002, Section 15C was left unamended.

History Repeats Itself with the COVID-19 Vaccine

Since October 2020, the WTO has been the site of a stand-off between the Global North and the Global South. In some ways, the proposal to temporarily waive IP rights to the COVID-19 vaccine has been more direct than Section 15C of the MRSCA ever was. On May 7, 2021, the United States announced its intention to back the proposal to grant developing countries access to vaccine patents, a hard-won, but still-tenuous, victory for a bloc of countries in the WTO led by South Africa and India.25 This change of position by the United States has been attributed to the mounting international pressure to acknowledge the rocketing COVID-19 infection rates in South America and India. The moral arguments were also paired with pragmatic concerns: the threat of new COVID strains could undermine the efficacy of vaccine rollouts in the US.26

Even powerful lobbyists who have long supported the position of the pharmaceutical industries have begun to reverse their stances. The week before the United States’ announcement, Bill Gates, co-chairman of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which essentially led the US pharmaceutical coalition arguing against the WTO proposal, met with US Trade Representative Katherine Tai to make the case against lifting patent rights. Gates questioned whether the manufacturing and regulatory capabilities in developing countries could allow for the creation of safe and high-quality vaccines, laughing in frustration at the suggestion that his true conflict was with IP rights.27 Yet, in the wake of the May 7 decision by the United States, the Gates Foundation, too, has reversed its stance.

Gates’ preference for protecting IP rights is unsurprising—much of his personal fortune is derived from patent rights—and he has previously advocated this position over democratizing access to critical healthcare.28 In 2010, Unitaid, a global health initiative based in Geneva, established the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP).29 The licenses that MPP negotiates allow other manufacturers to create generic versions of patented drugs for distribution in developing countries. However, the Gates Foundation, which represents the “constituency of foundations” on Unitaid’s Executive Board, voiced opposition to MPP.

Despite Gates’ reversal on COVID-19 vaccine patents, Germany, the pharmaceutical powerhouse of the European Union and home to BioNTech, has voiced opposition to the move, reiterating Gates’ supposed concerns about quality control.30 The European Union is now the only major geopolitical power still blocking efforts to increase global access to the vaccine. Even if the German government were to follow the example set by the United States and change its position, it isn’t clear whether the government could compel companies to collaborate. Vaccines, especially those that use new technologies, are more complex than HIV antiretrovirals. The patents, in this case, do not contain enough information to mimic a company’s product, preventing manufacturers from making generic versions of the vaccines. Doing so would require the sharing of trade secrets that governments currently have little power to force companies to disclose.31 Any sincere commitment to making COVID-19 vaccine technology accessible on a broad scale would entail enforcing an unprecedented and mandatory trade secret transfer in addition to an IP rights waiver.

The situation is dire. Immediate action must be taken to address the horrifying disparities in vaccine distribution around the world. As of May 2021, 0.3% of vaccines have been administered to the twenty-nine poorest countries in the world, home to 9% of the global population. By contrast, 44% have been administered to richer countries representing just 16% of the population.32 More than three thousand people die of COVID-19 in India every day. How can we motivate governments to take appropriate action?

Public criticism in 1998 led to victory for the citizens and government of South Africa. Similar pressures from the general public and international governments just this year spurred the United States and the Gates Foundation to reverse their positions on the WTO proposal.33 An unprecedented amount of public outcry, both domestic and international, will be needed to motivate the governments and companies that continue to push back against these common-sense measures to change their minds. The growing threat of new and vaccine-resistant strains of the virus will add fuel to the fire. At this point, every voice counts. Let history teach the citizens of Europe what to do.

—

Jacklin Kwan is a journalist based in Manchester, United Kingdom. She has written for Wired UK, Container Magazine, and Footprint Magazine on science, emerging technologies, and the environment.

References

- Philip Blenkinsop, “Rich, Developing Nations Wrangle Over COVID Vaccine Patents,” Reuters, March 10, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-wto-idUSKBN2B21V9.

- Emiliano Rodríguez Mega, “COVID Has Killed More Than One Million People. How Many More Will Die?,” Nature, September 30, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02762-y.

- UNAIDS/WHO, “Report on the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic—June 1998.” 1998.

- South African Department of Health, “National Drug Policy for South Africa.” 1996.

- South African, “National Drug Policy.”

- Martin Wittenberg, “Wages and Wage Inequality in South Africa 1994-2011: Part 1 – Wage Measurement and Trends,” South African Journal of Economics 85, no. 2, (2016): 279-297, https://doi.org/10.1111/saje.12148.

- Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation, “Background Paper: Income, Poverty and Inequality,” 2014.

- Keith Alcorn, “Brazil Issues Compulsory License on Efavirenz,” Aidsmap, May 7, 2007.

- Willam W. Fisher (III) and Cyrill P. Rigamonti, “The South Africa AIDS Controversy: A Case Study in Patent Law and Policy,” Harvard Law School, (2005), https://doi.org/10.7892/boris.69881.

- Fisher (III) and Rigamonti, “The South Africa Aids Controversy.”

- Meredith Wadman, “Gore Under Fire in Controversy Over South Africa AIDS Drug Law,” Nature 399, no. 6738 (June 1999): 717-718, https://doi.org/10.1038/21472.

- James Love, “Appendix B: Time-Line of Disputes over Compulsory Licensing and Parallel Importation in South Africa,” Consumer Project on Technology, August 5, 1999, http://www.cptech.org/ip/health/sa/sa-timeline.txt.

- Peter K. Yu, “The Objectives and Principles of the Trips Agreement,” Houston Law Review, 46 (2010): 979-1046, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1398746.

- Robert Weissman, “A Long, Strange TRIPs: The Pharmaceutical Industry Drive To Harmonize Global Intellectual Property Rules, And The Remaining WTO Legal Alternatives Available To Third World Countries,” University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law 17, no. 4, (1996): 1069-1076, https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/jil/vol17/iss4/2.

- Pharmaceutical Patent Issues: Interpreting GATT: Hearings Before the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, One Hundred Fourth Congress, Second Session…S. 1277, a Bill to Provide Equitable Relief for the Generic Drug Industry, and for Other Purposes, February 27, and March 5, 1996, (United States: US Government Printing Office, 1997).

- Pharmaceutical Patent Issues.

- Ramesh Govindaraj, Michael R. Reich, and Jillian C. Cohen, “World Bank Pharmaceuticals,” HNP Discussion Paper Series, (Washington: World Bank, 2000), http://hdl.handle.net/10986/13734.

- Patrice Trouiller et al., “Drug Development for Neglected Diseases: A Deficient Market and a Public-Health Policy Failure,” The Lancet 359, no. 9324, (2002): 2188-2194, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09096-7.

- Leo Lewis, “Can Drug Giants Swallow This Bitter Pill?” The Independent, February 16, 2014, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/can-drug-giants-swallow-bitter-pill-9131590.html.

- Charles Babcock and Ceci Connolly, “AIDS Activists Badger Gore Again,” Washington Post, June 18, 1999, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/campaigns/wh2000/stories/gore061899.htm.

- “Al Gore, AIDS Drugs and Pharmaceutical Money,” OUCH! Public Campaign, June 16, 1999, http://www.publicampaign.org/ouch6_16_99.html.

- Love, “Appendix B.”

- Phyllida Brown, “Cheaper AIDS Drugs Due for Third World…,” Nature, May 18, 2000, https://doi.org/10.1038/35012760.

- Pat Sidley, “Drug Companies Withdraw Law Suit Against South Africa,” British Medical Journal, April 28, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7293.1011.

- Amanda Macias, Kevin Breuninger, and Thomas Franck, “U.S. Backs Waiving Patent Protections for Covid Vaccines, Citing Global Health Crisis,” CNBC, May 5, 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/05/05/us-backs-covid-vaccine-intellectual-property-waivers-to-expand-access-to-shots-worldwide.html.

- Andrea Shalal, Jeff Mason, and David Lawder, “U.S. Reverses Stance, Backs Giving Poorer Countries Access to COVID Vaccine Patents,” Reuters, May 5, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/biden-says-plans-back-wto-waiver-vaccines-2021-05-05/.

- Adele Peters, “The Gates Foundation, COVID-19, and the Race for a Vaccine,” Fast Company, December 3, 2020, https://www.fastcompany.com/90579390/inside-the-gates-foundations-epic-fight-against-covid-19.

- Dean Baker, “The Secret to the Incredible Wealth of Bill Gates,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, June 20, 2016, https://cepr.net/the-secret-to-the-incredible-wealth-of-bill-gates/.

- William New, “UNITAID Drug Patent Pool Implementation Hinges On Board,” Intellectual Property Watch, December 11, 2009, https://www.ip-watch.org/2009/12/11/unitaid-drug-patent-pool-implementation-hinges-on-board/.

- Dharshini David, “Covid: Germany Rejects US-backed Proposal to Waive Vaccine Patents,” BBC, May 8, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-57013096.

- Jorge Contreras, “US Support for a WTO Waiver of COVID-19 Intellectual Property—What Does it Mean?” Bill of Health, May 7, 2021, https://blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2021/05/07/wto-waiver-intellectual-property-covid/.

- Staff and agencies in Geneva, “Vaccinate Global Poor Before Children in Rich Countries, WHO Says,” The Guardian, May 14, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/14/vaccinate-vulnerable-global-poor-before-rich-children-who-says.

- Kurt Schlosser, “Gates Foundation Reverses Position on COVID Vaccine Patent Protections After Mounting Pressure,” GeekWire, May 7, 2021, https://www.geekwire.com/2021/gates-foundation-reverses-position-covid-vaccine-patent-protections-mounting-pressure/.