Us and Them:

On the Discriminatory Use of Infectious Diseases Discourse

By Silvio Paone

Volume 27, no. 1, Rethinking Science Communication

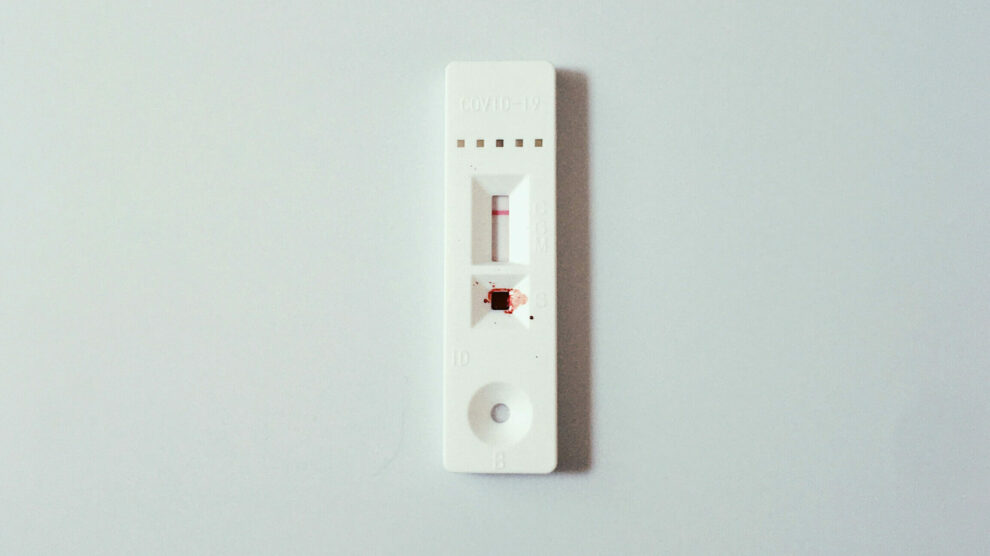

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Western countries were taken aback. The public could not believe that in the 21st century, a virus could inflict such widespread suffering in supposedly healthy and sanitary societies. After significant efforts and investment to combat infectious diseases in the latter half of the twentieth century, the West had largely relegated infections—historically a major cause of death—to a secondary concern. When encountering terms like “infection,” “epidemic,” or “contagion,” many in the West are prompted to think of developing countries in Africa, Asia, or South America. This notion is fundamentally misguided because of a racist discourse on public health that unduly exalts Western handling of communicable diseases. In truth, the last century witnessed at least six major epidemics of international concern: the Spanish flu, the Asian flu, the Hong Kong flu, HIV, SARS, and the swine flu.

Although multiple epidemics have afflicted Western countries in the recent past, their media, political leaders, public health authorities, and popular science have long perpetuated a narrative that the West has triumphed over infectious diseases. This appears to coincide with a broad shift in funding support to focus instead on non-communicable diseases such as cancer and aging-related illnesses—issues linked to the increased life expectancies and consumerism.International health organizations and charities are left to provide financial support to protect the West from those who are still suffering from the neglected infectious diseases. This perspective is well articulated in the recent book Grazie, Occidente by the prominent Italian journalist Federico Rampini, a staunch advocate of the “Western block,” who arguesthat humanity must be grateful to the West for its role in fighting infectious diseases in the Global South through nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and charitable programs.1 Here I argue that racism and xenophobia deflect attention from the structural issues that influence the spread of disease and the impact of epidemics on communities. I will show that the phenomenon of stigmatization or associating infectious diseases with specific, often marginalized, groups is not new and in fact has been foundational to the development of modern public health policies. In fact, I suggest that scientific discourse and education have reinforced these xenophobic tendencies, using analogies and metaphors that frame the relationship between human bodies and microorganisms in dualistic terms. To demonstrate this phenomenon, I will first describe historical and contemporary examples of stigmatizing processes linked to communicable diseases. Then, I will propose theoretical tools from Said, Levins and Lewontin to analyze such processes. Lastly, I will mention some examples of alliances between science and oppressed subjects and describe proposals to move the scientific community toward a more just scientific discourse and practice.

The construction of Western identity around a supposed immunity to infectious diseases has been foundational to modern health policies and has shaped scientific discourse from the outset. During the colonial era, European invaders brought various illnesses to the Americas, while diseases previously unknown in Europe began to circulate after the return of these European colonialists. Soldiers returning to England were labeled “tropical invalids” due to the illnesses they contracted abroad, prompting authorities to pathologize tropical regions, characterizing them as “places that need to be cured,” inhabited by people deemed dirty and wild, and marked by “impure air,” while the air in England was described as “too pure for slaves to breathe.”2 Colonial institutions were primarily concerned with the spread of diseases that hindered economic growth and market expansion. From the mid-nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, fourteen international sanitary conventions were held to solidify public health policies that also intensified the stigma against colonized peoples, who were often disproportionately marked, traced, isolated, and quarantined.3

From this context emerged a scientific discourse on infection that established a divide between Western societies, depicted as healthy, and foreigners, depicted as sick invaders, that was fueled by dominant theories like social Darwinism and eugenic studies. This narrative systematically obscured the diseases that Western invaders carried to the rest of the world and erased from collective memory the long history of epidemics, diseases, and contagion that has characterized Western history from its beginning. Over time, the West became a symbol of health, while everything external to it became a symbol of sickness that needed to be “cured” or “isolated”.

One of the most transparent examples of this racist narrative is evident in Western media’s reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to early surges of the virus, both Tanzania and Sweden decided not to implement quarantines or strong social distancing measures. While the Swedish policy was touted as the “Swedish model” and a potential “strategy” to prevent further spread of the virus, Tanzanian policy was ridiculed as “counterintuitive” and “toxic.”4 China and Chinese people were often blamed for the origination of the virus, and American President Donald Trump repeatedly downplayed both the rapid spread of the virus and the significant death toll among lower-income populations in the United States. While he was inattentive to the devastation caused by the virus in the US, he remained fixated on its alleged origins, labeling it the “Chinese virus” and “Kung Flu.”5 Even the Wall Street Journal published a racially charged article titled “China is the Real Sick Man of Asia,” echoing colonial-era prejudices.6 Such rhetoric inflamed anti-Asian racism in the U.S. and provoked strong reactions from the Chinese government.7 This anti-Chinese campaign was not confined to the US. In Italy, the virus was often labeled the “Wuhan virus,” with right-wing political figures like Matteo Salvini, the current Vice Prime Minister in Meloni’s xenophobic government, accusing the Chinese government—without evidence—of intentionally creating and spreading the virus to weaken Western economies.8 In February 2020,when the virus was thought to be still outside Italy, health authorities recommended banning flights from China, furtherstigmatizing and isolating Chinese communities.9

Similar discrimination surfaced in Italy during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Africa, tied closely to existing anti-immigrant sentiments toward Africans. Several Italian cities led by right-wing parties enacted “anti-Ebola rules” that discriminated against African migrants as possible carriers of the virus to Italy. In Padua, the ridiculous text of the law had very little to do with Ebola prevention and instead talked about migration, a sea rescue in the Mediterranean Sea, the number of migrants in the Padua area, and the fact that two police officers got scabies during an operation involving migrants. The rule banned any person without an ID card from city territory and forced migrants with no regular residence permit to go to the local hospital to check for their health conditions. The links between the content of these laws and the risk that a city in northern Italy could be destroyed by an Ebola epidemic that was still limited to west Africa are a mystery.10 What happened in Italy perpetuates the broader racist narrative on Ebola. The spread of Ebola in western Africa was largely attributed to local beliefs and a distrust in science, rather than the combination of underwhelming global support in the face of a serious health crisis, overall poor health conditions due to an absence of functioning public health systems, and comparatively low standards of living stemming from centuries of colonialism. This narrative reinforces the notion that Africans are disproportionately afflicted with infectious diseases due to their “primitive” culture and superstitious beliefs, which supposedly lead them to reject rational, Western health policies.11 Meanwhile, it deflects attention from the broader structural disparities and delayed international health response, seen by many as neglect or even abandonment, to the Ebola outbreaks in 2014.

Not only have marginalized communities been characterized through analogies with infectious diseases, but the reverse is also true: infectious diseases and pathogens have often been named after human communities or geographical locations.Such a case is the 1910 cholera outbreak in Naples—a city in the south of Italy historically marginalized by the north since Italy’s unification. In 1910, American physician Henry Downes Geddings, serving as a public health official in Naples, alerted the Italian government to the rapid rise of cholera cases and urged action to prevent a wider epidemic. In response, Italian political and health authorities downplayed the severity of the situation to avoid economic repercussions, branding the disease as “febbre napolitana” (Neapolitan fever) and dismissing it as a mere gastroenteritis that would not spread beyond Naples. Meanwhile, cholera from Italy reached the US, France, and Libya, where it was probably carried by Italian colonial troops.12 Even today, Neapolitans continue to face discrimination and are referred to as “colerosi” (literally “cholera-stricken”) by racist chants at Italian football matches, which pray for Vesuvius to erupt and “wash” the “dirty Neapolitans.” This exemplifies how the blaming of a particular group for infectious disease serves as a distraction from the economic and political causes of disease spread.

Scientific Discourse on Infection: A Matter of War, Invasions and Repression

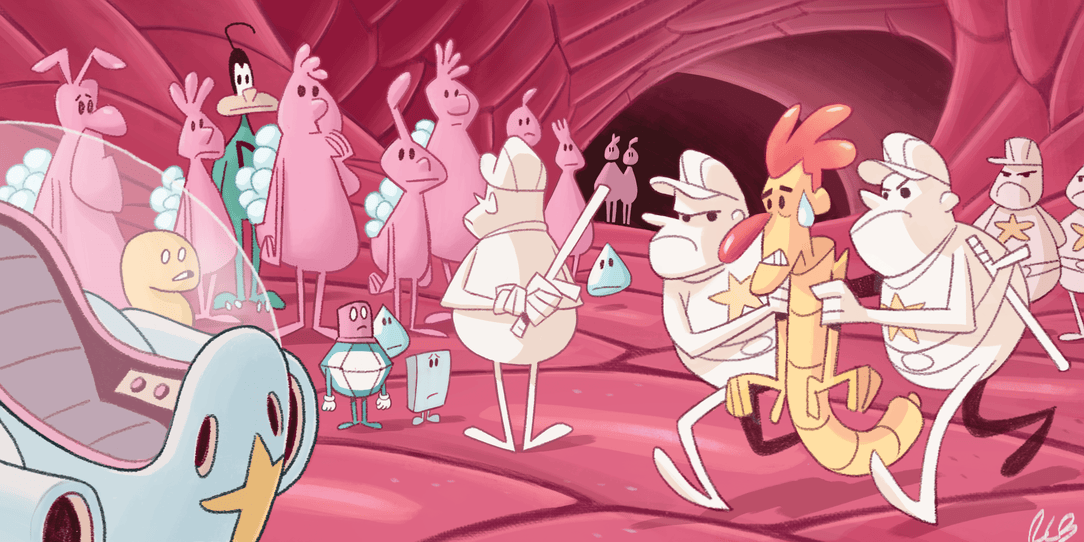

In the educational cartoon Once Upon a Time… Life human cells and tissues are depicted as a society resembling an average Western community, where immune cells are represented as policemen in white uniforms that must identify foreign invaders. These invaders, viruses, and bacteria are cast as villains, often with yellow skin.

In his popular work Orientalism Edward Said stated that colonialism not only depends on physical violence and conquest but also on the psychological and epistemological representations of the “Other.” These representations of the “Other” reveal power relations between people in a process that Said calls “Otherism” that constitutes the cultural background on which imperialism and colonialism grow.13 The scapegoating of the savage, primitive, and sick “Other” has little to do with empirical knowledge of a particular phenomenon but is a powerful tool to reinforce existing, oppressive hierarchies.

The truth is that our immune system functions in a way that extends beyond mere defense against external threats and infections. In fact, there are billions of bacteria that normally live inside our body, constituting our “microbiota,” which are essential for homeostasis and healthy immune function. We are constantly “infected” or sensitized to various pathogens that do not cause harm and often go unnoticed. Indeed, a significant portion of human DNA is of viral origin, indicating that our genetic material has been shaped by past infections. For example, transposable elements, which are viral sequences, continue to move within our genome, contributing to essential biological processes including the production of antibodies from immune cells. This means that these cells can recognize viruses, thanks to the remnants of ancient viruses.

In The Dialectical Biologist Richard Levins and Richard Lewontin level a similar critique as Said that focuses directly on the biological sciences. They criticize a dominant Cartesian view that describes every biological entity and process as isolated and argue that interaction is more important than identity and the process is more important than the subject.14 In fact, the scientific thinking that arises from a Cartesian tradition often emphasizes a stark separation between “self” and “non-self,” framing human bodies as distinct from the external world, rather than acknowledging the shared evolutionary history of interaction and co-evolution between humans and their environments. Language borrowed from warfare oftenpermeates this discourse. For example, during an epidemic, we are said to be “at war” with the disease, with health professionals “fighting on the front lines.” Microorganisms “invade” a cell, while viruses are described as “cell hackers.” The immune system is often portrayed as a military organization tasked with protecting “self” by identifying and attacking “non-self” invaders.

We see how bourgeois scientific thinking lends itself to the process of “Othering” and downplays the complexity that is in motion during an infection. This does not negate the reality that many microorganisms can cause severe diseases or that Western medicine has significantly reduced the burden of certain infections for many people. While the scientific narrative can reflect xenophobic perspectives, our understanding of microbial interactions has never been deeper. It may sound counterintuitive, but it is not. We should not try to destroy existing knowledge and start from zero. Relativism is not the answer. Instead, we should center this knowledge in a new light and consider all natural phenomena under a new framework that is not reductionist under the “epistemic” point of view and not discriminatory when applied to a broader cultural environment. This can be done only by recognizing that a reductionist and discriminatory framework is a hindrance to further understanding of natural phenomena, social acceptance of scientific knowledge, and effective prevention and response during health emergencies. Moreover, it can be done by nurturing alliances between social struggles and radical scientists. There are many examples where social movements have led the charge and significantly altered the terms and relationships among institutions, scientists, and the public. This is true of the social movements who organized against anti-gay rhetoric early during AIDS epidemic and fought to protect the dignity and secure rights for people living with HIV and research participants, as well as universal access to life-saving medications.15 During the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese communities organized to counter sinophobia and created networks and associations to make mutual care, health, and solidarity the basis of a new, more just society.16 Alternative practices also emerged in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. One example is Pandemic Research for the People, a crowdfunded project aimed at improving public awareness and understanding of the complex issues communities continue to face.17

We, as radical scientists, know that the role of science goes far beyond the mere production of discourse but regards the health, wealth, salvation or possibly destruction of billions of people, mainly the poorest, marginalized, and oppressed ones. With them, we have to walk together.

—

Silvio Paone, Ph.D.: Silvio is a molecular biologist with a PhD in Infectious Diseases and Microbiology. He works as a researcher at the Italian National Institute of Health (ISS), specializing in malariology. Since his time as a biology student at the University of Rome, he has been actively involved in organizing social movements, with a particular focus on the social dimensions of scientific production. Currently, he is an activist in the Italian chapter of Scientists for Global Responsibility (SftP). Facebook, Instagram

Notes

- Federico Rampini, Grazie Occidente! (Italy: Mondadori, 2024).

- Alan Bewell, Romanticism and Colonial Disease, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003).

- Alexander I.R. White, “Historical linkages: epidemic threat, economic risk, and xenophobia,” The Lancet 395 (April 2020): 1250-1251, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30737-6/fulltext.

- Leanne Loo, “Capitalizing on Lock Down while Locking Down on Capital,” Science For The People 24 no.1, June 2021, https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/vol24-1-racial-capitalism/imperialism-and-covid-19-in-tanzania/.

- Colby Itkowiz, “Trump again uses racially insensitive term to describe coronavirus,” The Washington Post, June 23, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-again-uses-kung-flu-to-describe-coronavirus/2020/06/23/0ab5a8d8-b5a9-11ea-aca5-ebb63d27e1ff_story.html.

- Walter Russel Mead, “China Is the Real Sick Man of Asia,” The Wall Street Journal, February 3, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-is-the-real-sick-man-of-asia-11580773677.

- Yulin Hswen et al., “Association of “#covid19” Versus “#chinesevirus” With Anti-Asian Sentiments on Twitter: March 9–23, 2020”, American Journal of Public Health 111 no. 5, May 2021: 956-964, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306154; “Trump angers Beijing with ‘Chinese virus’ tweet”, BBC, March 17, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-51928011.

- “Coronavirus, Salvini: “la Cina cresce, a pensare male si fa peccato ma…””, Affaritaliani, April 14, 2020, https://www.affaritaliani.it/politica/coronavirus-salvini-la-cina-cresce-a-pensare-male-si-fa-peccato-ma-665875.html.

- “Coronavirus, Amnesty International Italia: ‘Vergognosa ondata di sinofobia’”, Amnesty International, February 4, 2020, https://www.amnesty.it/coronavirus-amnesty-international-italia-vergognosa-ondata-di-sinofobia/.

- Ivana Abrigiani, “Emergenza ebola – Il razzismo è una malattia contagiosa”, MeltingPot Europa, December 9, 2014, https://www.meltingpot.org/2014/12/emergenza-ebola-il-razzismo-e-una-malattia-contagiosa/.

- Eugene T Richardson, Timothy McGinnis, Raphael Frankfurter, “Ebola and the narrative of mistrust”, BMJ Journal of Global Health 4, no. 6 (December 18, 2019), https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001932.

- Riccardo Liberatore, “L’Italia ai tempi del colera. Quando il governo Giolitti nascose un’epidemia che contagiò il mondo”, Open Online, February 2, 2020, https://www.open.online/2020/02/02/litalia-ai-tempi-del-colera-quando-il-governo-giolitti-nascose-unepidemia-che-contagio-il-mondo/.

- Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978).

- Richard Levins and Richard Lewontin, The Dialectical Biologist (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985).

- Paula A. Treichler, How to Have Theory in an Epidemic (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999).

- Care Collectives, The Care Manifesto (Verso, 2020).

- “Pandemic Research for the People”, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.prepthepeople.net/.