Sowing Ancestral Futures

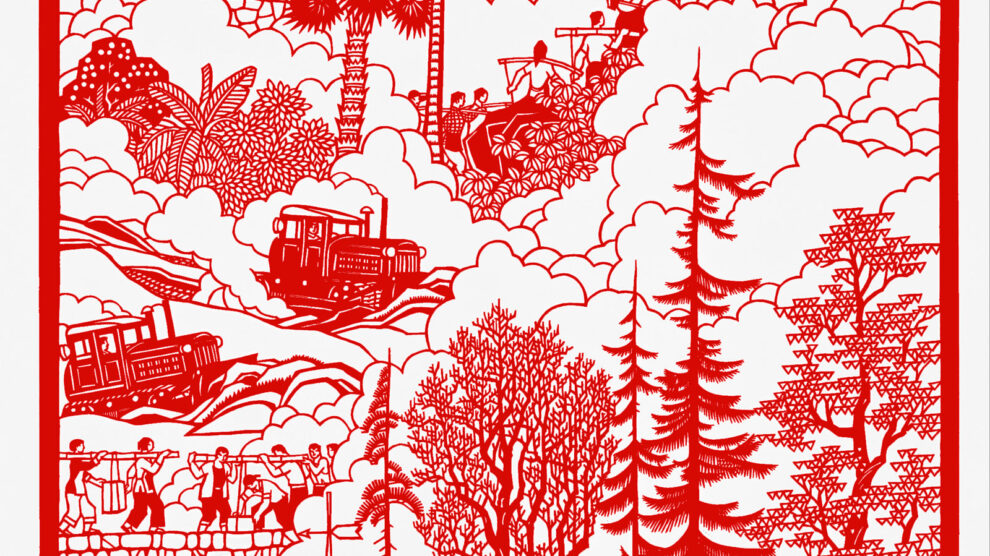

An interview with Yowar Mosquera Rivas, cofounder of Protectores de la Tierra In Colombia

By Sara Gutiérrez

Volume 26, no. 2, Ways of Knowing

Introduction

“The rivers are the veins of the land,” says Yowar Mosquera Rivas, relaying a lyric from a visiting cantadora, a female poet and singer who sang the night before we spoke. Yowar lives in Nuquí, Chocó on the Pacific coast of Colombia, the home to many Afro-descendant communities who have asserted collective ownership to land, based on legal precedent passed in 1993. Established in Law 70, it recognized the ethnopolitical autonomy of Afro-Colombians and formalized the territorial rights and political authority of five million hectares of land to Black community councils, although still up for debate.1In this context, Yowar co-founded Protectores de La Tierra (Earth Protectors), a food sovereignty project dedicated to the relearning and reclamation of ancestral knowledge.

The natural environment in the department of Chocó is, as they say fuerte, “strong,” or intense. As one of the rainiest places in the world, the region experiences hazardous floods that damage homes and crops. The rainforest is incredibly dense, the humidity is thick, and it is very hot all year round. These conditions have also created an abundant natural paradise—the Chocó is a hotspot for biodiversity, ranked among the top ten places in the world. For instance, this region encompasses twenty different types of ecosystems. It is also home to the annual site of humpback whale migration. In place of roads, the lowland jungles are navigated with modern and traditional boats by a sprawling network of rivers and their tributaries.

Knowledge of how to work the land in Chocó is particularly geographically rooted due to the unique rhythm of life that the waterways create and the various floor types available to farm. The tides’ behaviors that dictate daily schedules, also allow farmers to navigate sprawling mangroves; the diverse floors and soil types that require broad stewardship also provide the conditions for a diversity of crops. The “aquatic space” in the Pacific is more than just a physical network of rivers, rainfall, and sea: it is the quotidian itself, a life materially, culturally, and spiritually interwoven into the water systems.2 The environment cannot be ignored or dominated, it must be understood and “known.” This ancestral knowledge is specific to the region and history of the Afro-Colombian and the Embera communities. They share the rivers with the Indigenous peoples, the Embera, who have led environmental activism to preserve the ecology and land they have lived on, and with, far before colonial presence in the continent.

The Afro-descendent communities have adapted and developed a way of life known as “Buen Vivir” (“good living”).3 Now prevalent in Black and Indigenous communities across the continent, Buen Vivir “considers Nature as a living being, a subject of care and rights,” as in Mother Earth Subverting notions of Western development, Buen Vivir rejects “the linear idea of progress” and centers a “relational conception of all life.”4 Many of the buildings are built on stilts, several feet off the ground. There are numerous festivals that celebrate Afro-Colombian culture and heritage. Recent efforts to build a port in Nuquí have been thwarted by local environmentalists and social leaders, and resisting the negative environmental effects that plagued neighboring Buenaventura, the largest city in Chocó, and the development of its own bustling port.5

In times of conflict or climate-related disruptions, the communities around Nuquí have felt the collective strain in terms of severe food insecurity. For instance, the Colombian armed conflict (1964-2016) displaced thirty-six percent of the Black population since 2008, and much of the passed down knowledge of land stewardship was weakened, if not lost, for many.6 These insecurities were further exacerbated when the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in 2020, when local and regional supply chains were disrupted. The town is dependent on imported, commercially supplied food brought in by air and sea, and soon the community experienced dwindling sources of provisions and increasing food prices. The negative consequences of regional reliance on imported food became painfully clear. Yowar says that it didn’t have to be this way. Some decades ago, according to Yowar, Nuquí was so fruitful that the town exported crops to the rest of the country. With the recent drop in imported food costs and new kinds of products introduced, local farmers lost incentive to harvest locally and the community’s reliance on imports grew.

Taking action towards self-reliance and resilient futures, Protectores de La Tierra (PDLT) originally hired and now works collaboratively with several Embera families to teach various younger members of the Afro-descendent community in Nuquí. In a time where people are returning to their inherited lands in Chocó and the prices of necessary goods are increasing, communities are taking a powerful step in repudiating old norms; instead they are resurrecting and preserving ancestral knowledge as they cultivate their overgrown plots and engage in the cultural tradition of collective farming. Through solidarity and community building between two distinct but geographically tied communities, an alternative to traditional modes of western development is taking place to create a healthy and abundant future. In what continues below, Yowar offers insight into the inherited philosophy of his community, the unique nature grounding their way of life, and their dedication to preserving both.

Interview

SG: Hi Yowar, before we begin, can you share with us about yourself?

YMR: Hello, I am Yowar Mosquera Rivas, I’m from the municipality of Nuquí, Chocó, in the northern region of the Colombian Pacific coast. I am son and ombligado of a territory that is born on river banks and the Pacific ocean. I am a cultural creator, I am a farmer, I am an athlete—I surf—I work in my community, tying together the themes of community, cultural, and agricultural tourism. I am a son of Nuquí, the Chocó department, whose population is Afro-indigenous. I come from an Afro community by way of the Baudó river basin and the Panamanian pacific region. My grandparents, my ancestors are Black and Indigenous communities. That is where I come from, that is where Yowar Mosquera Rivas comes from, a person who wants to transform and recover all of these ancestral practices, through farming, through traditional music, through dance, through sport, through the conservation of our planet, the environment, and of humanity.

Here, all understand the way of life, by way of the elders raising this iteration, our generations to come, to sustain the ancestral dynamics. I believe that Nuquí is connected to a territory of living Nature. A living Nature, an intact Nature.

SG: Could you share an example, to help people who aren’t familiar with Colombia, or Nuquí, or the region, of how it is there? An example of how in a day, or week, or month, how the water, whether it is the rain, the sea, the rivers, impact the rhythm of life, of the people, the work, the rest, everything?

YMR: Nuquí is an Afro-Indigenous region, it lies four to five hours north of Buenaventura on the Chocoano Pacific coast. It is a community focused on tourism for the natural beauty we have. Nuquí is a cultural, ethnic, ancestral, and rooted territory. Here, all understand the way of life, by way of the elders raising this iteration, our generations to come, to sustain the ancestral dynamics. I believe that Nuquí is connected to a territory of living Nature. A living Nature, an intact Nature. It is a Nature that hasn’t been deforested, it is a place where there is no extraction of natural materials. It is a marvelous place, splendid, because we can count on the ocean, the river, the jungle. She is a one hundred percent organic territory because her land is very productive, anything can grow. There is a very strong concession that we respect a lot; for us, to enter into Nature or receive gratitude from her, we must follow her requirements which Nature is always telling us.

We always plant during the [full] moon, we cut trees or harvest during the waning moon. During some periods, we don’t cut or harvest. The tides always speak for themselves. Generally, the ocean waters rise and fall every eight hours. This transition determines how one can go places. I’ll go up to one place during low tide and to up to a farther place during high tide. Or I’ll head out early, because the tide is low, or I’ll head out late because the tide is high.

The moon, there is a very important connection with the moon that should not be forgotten. I also think that at some point, the sun was part of understanding time. Our grandparents used the sun to view the hour, or how the breeze blew. How the breeze blows, how the breeze arrives from the sea to the town, connects to knowing if it is rising or setting, without having to be close to the sea. The energy can be felt, and there continues to be a connection of all these knowings. For us to also create these farms, we need to know a lot about what seasons are relatively good for the sowing, for the harvesting. Our human connection with our environment is very important, because when we are newborns, our parents heal us with the energies of Nature [as a subject or force of Mother Earth], such as healing our belly button with medicinal plants or another part of Nature. Since we are little, we have a strong connection with her, because we are healed, cured, and in this way, have this connection. Because we don’t count on scientific medicines, rather ancestral medicines, there exists a connection with plants from a young age. To get rid of a fever, to get rid of a cold.

Everything reflects the connection with the environment, the territory, the lives of all. The animals have this sensibility. Because they graze in some places in winter, or summer. Nature makes them also change locations, and look for other foods in other places. It is this transition that decades ago, these places have been like this, that was sustained. There has been no dedication to the theme of exploiting our Nature. It is a very protected territory, so there exists these physical and energetic connections. For decades, I have been sensing, interpreting, and knowing more everyday.

One must learn; Nature speaks to us in her languages, natural interpretations.

SG: Have you seen difficulties that happen when one tries to resist, to work against the cycles of water?

YMR: I think this territory is one of the rainiest parts of the planet. So that makes it such that the jungle is more intense, stronger. I have had experiences with the rain or rivers flooding. One must learn; Nature speaks to us in her languages, natural interpretations. Sometimes we don’t interpret those signs; when I was first starting to farm, I sensed an imbalance, [in this] situation with Nature. The river rose, and it rained for a long time, and it washed away all the crops that I had recently planted. There was much loss. But entering in a connection with Nature, living with her, being in balance with her is more important and safe. It is surely more productive, because you can’t turn against her; instead you become part of the transformations of Nature and expressions of Nature that are giving us constant wisdom. But it is water, it’s rain. Water is life, if we don’t count on this precious liquid, well how are we going to have it for the plants, for the crops. Thanks to the rain, we can count on the super fertile territory, being super productive, and one hundred percent organic. We never add chemicals to the earth. In some way it [Nature] leaves you the lesson that you can sow in one place and not in another place, what dates you can cultivate, and what dates you can’t because of the tides and the river, the intense rain, it can remove everything. So then water is life, it is also part of the process.

SG: The Nuquí river is shared by Indigenous and African descendant communities. Do you know historically or in your life, how the populations have interacted, and if in the pandemic, if the supply chain problems impacted both populations equally or differently?

YMR: Yes, we are a community that has always shared the territory, Black communities and Indigenous communities, that makes it so our population is very ethnically ancestral, in this cultural reunion. A friendship exists and has existed, that are connections of togetherness, that the two communities have always had. Sure, the impact [of the pandemic] came out of nowhere. The communities were releasing some of their farmland, the Indigenous communities have more so had their resistance, because they are provided for by the Earth, they eat there, they make their homes there, they carry out their ancestral dynamics. But our Afro communities shed a lot [from the territory] because of modernism, all the new things that arrive, social change. So they disengage from following the ancestral dynamic, by having everything accessible at hand. So it is a community that has always been united. In addition, the territories are covered by Law 70 that are laws made 50 years ago under these dynamics of safe protection: the territory cannot be sold, it cannot be cut, rented to companies that come to exploit the territory. Land cannot be sold without the endorsement of the community. So that law is very important; [from there] the territory has been sustained, because of that safe protection, all this knowledge has formed, all the togetherness, and it still continues.

SG: This process of relearning knowledge, besides the more visible aspects, like the physical things, like the crops and the grounds, and the food, how has the project impacted your relationships? Your relationships with your neighbors, with the elders, with the youth, and your relationship with the territory that you have lived on your whole life?

YMR: In reality, we have felt a lot of important energy from the community. Gratitude, contributing, acknowledging, what we have developed in our community. At first, it was very difficult, for our Nature is very special, very strong, it requires a lot of commitment, a lot of dedication and time. We have humid soil, sandy soil, mountainous soil, and thanks to that there can grow a variety of products that provide a lot for our familial well-being and nutritional sustainability.

There has been a great personal impact. We work with two, three Indigenous families. Each family has between 15-20 people, including youth, kids, and elders. And within the community we work a lot in the neighborhood. The Calle la Virgen neighborhood, because it is a neighborhood that is very close to the river, it’s accessible to come and go. So yes, the gratitude, the energy from the elders, that they count on with that strength, they were encouraged and had the capacity to go to the river and cultivate its land for long periods of time. But today because of illness, or age, they can’t make these routes, these dynamics—for example, in the case of my grandmother.

The terrain, the farm, the river, the conditions have been adapted so that the elders, who cultivated for decades, could step on a productive land, a process that has a territorial, natural, ancestral ethnic dynamic. Much satisfaction from the elders, they’re always asking, I’m always sharing some of the fruits, a pineapple, a lulo, or a plantain. So there has been a very strong connection. Not with all of the community because the project has only gone on for two years. But it has an intention and dynamics rooted in the territory to transform now and always. There is recognition for the process, to hear from the elders [who say]: son, I congratulate you all, for making something possible that hasn’t been done, because the relation to the territory changes when everything comes to you easily, there at your fingertips. So, yes there has been a lot of contribution from the community.

SG: How do you all make the decisions of which modern tools or techniques to get or implement, balancing with the ancestral practices?

YMR: Our community, for being such an isolated territory, is isolated from cities that have those practical tools for agriculture. I learned from my elders. I learned how to work without tools for the task. We are a community that has always used the machete, the axe, wooden stove, the traditional boat, the oar. I lived that [way] when I was young, and that is how our communities sustained themselves, through all these ancestral practices, super educational, always having these tools. But as we enter this evolution [use these practices], it is important to not lose this sensibility with the connection to the earth. Today in regards to agriculture, I rent tools that are very practical, because it helps the process to be faster, more efficient, more practical.

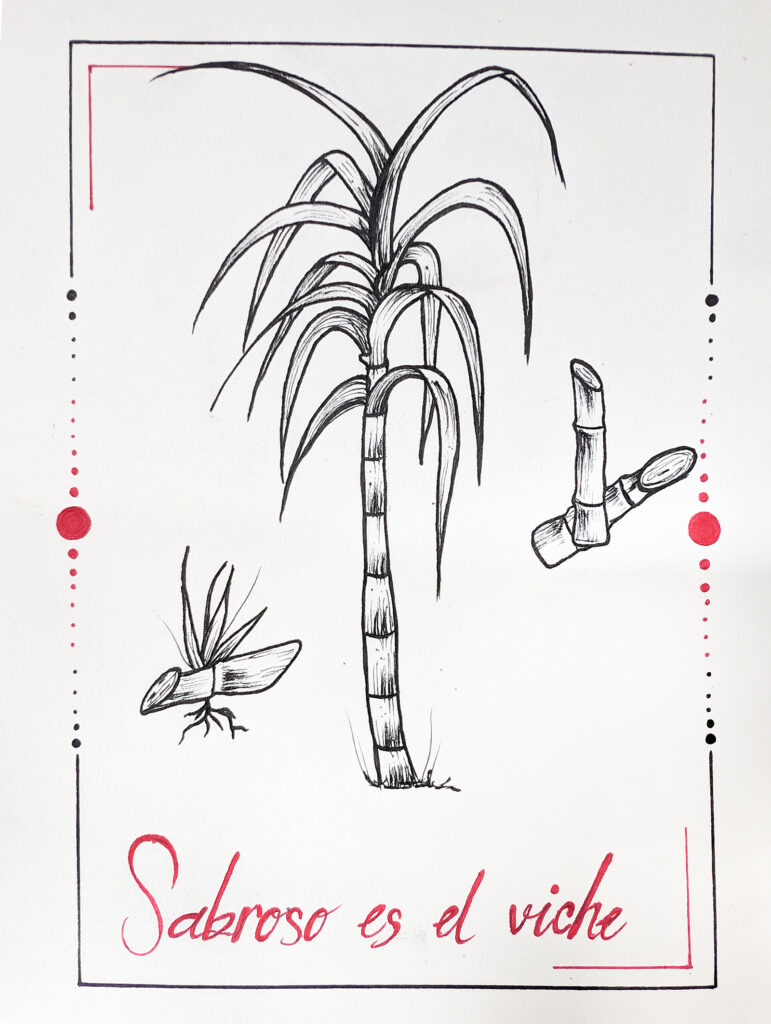

And we have been transforming in that way without leaving the ancestral knowledge. [Examples of these ancestral practices would be] how to put the seed in the ground, in what season, in what time, if we speak to the seed, if we hit the ground [after planting]. But to control Nature by way of a machete is hard and exhausting, so we use very practical tools like scythes or pruners. On the topic of transformation of raw material, I am cultivating a lot of sugar cane to make viche, which is a traditional drink from the Pacific. There are some ancestral tools that are made with products the jungle provides. And that’s how we lived. But there are more practical tools that help advance and quicken the process, to save time. We managed to obtain a rice mill, and this year we had a rice harvest, and through the mill, we were able to process this food to take it to our family more quickly, more easily, and more cleanly.

Now we have an electricity problem in the municipality of Nuquí. There is a fuel plant that has been used, but these last months electric energy has been being regulated. We are a territory with a lot of sun, many rivers, many tributaries, to transform and generate clean energy. So one of those [sources of clean energy] are these solar panels where energy is powered by the sun and can help avoid burning fuel. It is a processed energy to have good practices on the farm. If we have energy, we can transform a product. The tools are important so the project can advance with greater fluidity and there is no physical and economic wear and tear [from manual labor], which sometimes discourages everyone. That is what our elders did, and I have changed the dynamic a bit.

Our food sovereignty depends on ourselves. Because we count on ancestral knowledge of knowing the land, knowing the soil, knowing the seeds, knowing the lunar phases, I believe we have a very important role in our territory.

SG: What is the role of food sovereignty in a territory that has a strong environment and a strong history?

YMR: I can say that it’s not just myself, there are a few friends that [also] have seen us carry out these projects and have become motivated to work the land. It is a generational change that we want to continue sustaining and working on these practices of growing food. Our food sovereignty depends on ourselves. Because we count on ancestral knowledge of knowing the land, knowing the soil, knowing the seeds, knowing the lunar phases, I believe we have a very important role in our territory. From there, we understand that we’re going to be a self-sustainable community, a healthy community, because he who eats healthy rarely gets sick. My grandmother always told me that. He who eats well, healthy, so will his own growth be like on this planet. The process [PDLT] has been happening for two years. We have had many allies and local friends and from other places who like our project. Many are also part of this initiative. We count on the conditions of our territory, the company of the youth, elders, Afro communities, Indigenous communities, who see this unique opportunity, because everything is being lost, everything is being left behind, they are leaving everything to be forgotten.

Dynamizing the topic of farming with an emphasis on social transformation, food recovery, healthy eating, saving all of this knowledge, all our inheritance, all of this is a part of PDLT. It is a part of me, of all the allies that the project little by little is gaining. I know that this future will be a giant community coming to the rescue of food sovereignty. This is only now growing, only now working, only now trying to focus on the enhancement from the ancestral sowing. It is all part of a process that I have taken very seriously, because I believe that if there isn’t a leader that takes these places in the territory and sustains them and transforms them, nothing will happen. So I believe I have a commitment with Protectors [PDLT], with my community, with my ancestral knowledge, with my connection with Nature. To continue so this [all] is visible in the future. [A future] that is transformed, is energetic, is responsible, is responsive, is respectful. from there [these commitments], we are working so that this flows.

SG: What is your hope for this article?

YMR: I am a young man from the community of Nuquí, I am thirty-six years old, I learned from my elders. Yes, I am a community leader. I make traditional music, do sports, work in tourism, so all this knowledge clears my doubts and I see these projects like a door, so that everything can be transformed towards a more appropriate dynamic for the territory, [in addition to engaging with other movements and] corporating dynamics from other places. Because there is still that knowledge, there is still that ancestry, there is still that connection of human beings with Nature in these places. So I believe this article is another door to making all these processes visible that have been taking place, well so, because there are few opportunities that present themselves to give recognition to all of this community work. So I believe that well, that good energy, good connection, that this article reaches everybody, to all ears, to all races, to all languages. Because it is not only human beings that lives in Nature, so it is important that this magazine demonstrates all of our process of acceptability with Nature, with energetic connection with her.

SG: Well, thank you for everything. I’m very grateful for the opportunity to learn from you. I hope this coming year I can visit you all and go to the Tamborito festival and learn more in person. And if there’s time, share some of what I know about the Moon, and continue this relationship. In the meantime, I’m going to apply what I learned here in Cleveland.

YMR: Yes, this connection was like destiny. Perfect, thank you for everything.

Meet the contributors:

Sara Gutiérrez: Sara Gutiérrez is a colombian-american planetary geodynamicist planted in cleveland, ohio. They like to look at the Moon and study its deep interior processes, and play with their dog, Laika. They are guided by and committed to a future where all children have a relationship with the night sky and the liberation that world requires.

Twitter: @tierrasara

Notes

- Marcela Velasco Jaramillo, “The Territorialization of Ethnopolitical Reforms in Colombia: Chocó as a Case Study.” Latin American Research Review 49, no. 3 (2014): 126-152; Helmer Eduardo Quiñones Mendoza, Noah Rosen, and Jonathan Fox, “Titulación colectiva de los territorios afrocolombianos: Convergencias entre el movimiento de comunidades negras y funcionarios reformistas, 1995–2003.” [Delivering Collective Afrodescendant Land Rights: Mutual Empowerment in Colombian State-Society Coalitions 1995–2003.], Accountability Research Center (2023).

- Ulrich Oslender, The geographies of social movements: Afro-Colombian mobilization and the aquatic space (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016).

- Charo Mina Rojas et al., “Luchas del buen vivir por las mujeres negras del Alto Cauca.” Nómadas 43 (2015): 167-183; María Fernanda Ordóñez, Kelly Shannon, and Viviana d’Auria. “The Materialization of the Buen Vivir and the Rights of Nature: Rhetoric and Realities of Guayaquil Ecológico Urban Regeneration Project.” City, Territory and Architecture 9, no. 1 (2022): 1.

- Erika Arteaga et al, “Beyond Development and Extractivism,” Science for the People Magazine, 25, no. 2 (2022); Arturo Escobar. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. (Duke University Press, 2018), 148.

- Dimitri Selibas, “Battle over proposed Colombian port at Tribugá puts sustainable development in focus,” Mongabay, October 5, 2020; “Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Emberá,” Minority Rights Group International, October 5, 2020.

- Adrian Alsema. “West Colombia Guerilla War Causing Food Shortages.” Colombia Reports. June 15, 2018.