A Call to Action:

Cut Ties Between Education and the Fossil Fuel Industry

By Imperial Climate Action: Sebastian Gonzato, Peter Knapp, and Julia Mitra

Volume 27, no. 1, Rethinking Science Communication

The continued extraction of fossil fuels poses an immediate, existential threat to modern societies. Education of young people from childhood to university provides fertile ground for manipulation from the fossil fuel industry. The efforts to normalize fossil fuel dependency in transport, materials, energy, economic growth, and prosperity are widespread in educational settings at all stages. As students and alumni of Imperial College London (ICL), we are uniquely positioned to present our personal accounts and a case study of our collective participation in a campaign called Imperial Climate Action (ICA).1 We argue that there is an urgent need to change courses and syllabi, to cut ties with fossil fuel companies, and to foster a culture that empowers imagination, design, and creation of just and fossil fuel-free futures.

ICL continues to this day to work alongside companies such as Shell, BP, ExxonMobil, PETRONAS, Saudi Aramco and Qatar Petroleum.2 Many of these partnership deals were signed by ICL’s president Alice Gast (2014-22), who was on the board of Chevron. The authors are members of ICA, and the collaborators are all active members in the climate movement.

We are grateful to Science for the People for publishing this piece. Our original submission to the Journal of Chemical Education’s special issue on Action for Climate Empowerment in Chemistry Education was rejected as being “outside the scope” of the issue; one of the journal’s editors resigned over this decision. This, in our view, shows how difficult it is to challenge the relationship between fossil fuel companies and education.

We hope that this article will inspire readers, especially in the educational sector, to include the climate emergency into school and university curricula, to consider climate activism themselves, and to work with colleagues to create distance between education and the fossil fuel industry.

We Cannot Trust Oil Companies

As early as 1962, Shell’s chief geologist wrote a book-length report warning of the effect of rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels from burning fossil fuels.3 Evidence shows Exxon was well aware of climate change by 1977, eleven years before it became a public issue.4 A leaked 1978 Shell report described “severe stresses on human societies” of lower crop yields from burning fossil fuels.5 The infamous 1988 internal memo from Shell The Greenhouse Effect warned of climate impacts “larger than any that have occurred over the last 12,000 years.”6 Finally, a confidential 1989 Shell report warned that “many species of trees, plants, animals and insects would not be able to move and adapt,” and, with explicit xenophobic and colonial attitudes, that “the potential refugee problem […] could be unprecedented. Africans would push into Europe, Chinese into the Soviet Union, Latins into the United States, Indonesians into Australia. Boundaries would count for little—overwhelmed by the numbers. Conflicts would abound. Civilisation could prove a fragile thing.”7

But, despite the extensive awareness of the worldwide and irreversible consequences of fossil fuels on society, biodiversity, and conflict, the industry chose to hide this from the public and instead start a campaign of disinformation and lobbying for more fossil fuels that continues today.

Racial capitalism and related violence remain common practice for many oil companies that amplify the risks of the most vulnerable to climate change. One example is the key involvement of TotalEnergies in the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) that will lead to the region becoming uninhabitable.8 Protest continues to be aggressively silenced, to the extent that Amnesty International found evidence the company was complicit in the execution of nine Nigerians who peacefully protested oil leaks in the Niger Delta.9

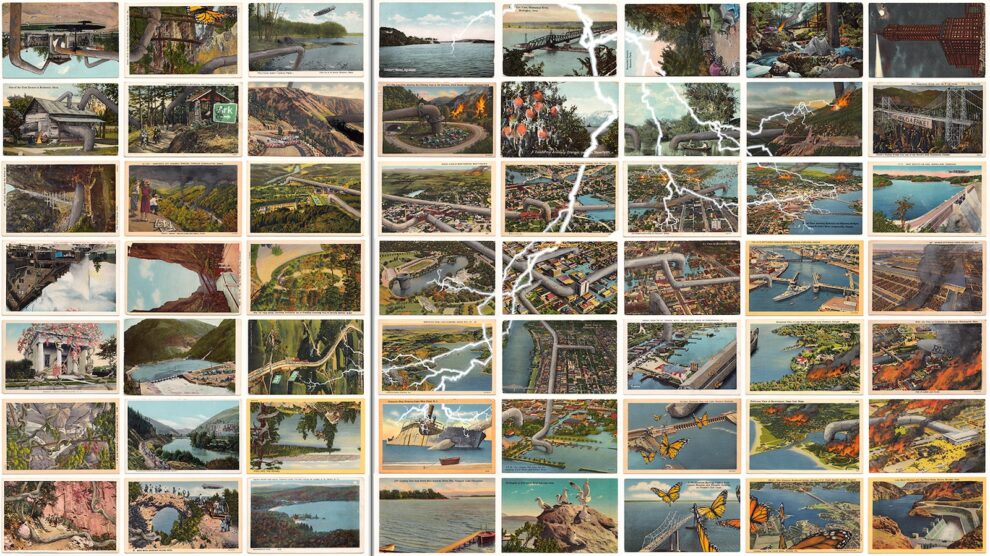

For decades, fossil fuel companies have, and continue to, plow billions into denial, lobbying, disinformation, and manipulation campaigns designed to delay climate action through tactics such as, but not limited to: These interventions from the fossil fuel industry have facilitated an unabated, exponential rise in carbon emissions and consequently devastating increases in food crises, droughts, fires, floods, and mass migration. The future of young people is not the same future that fossil fuel companies promote, and we have to be proactive in removing the industry’s social license to operate. This demands a focused effort to remove the fossil fuel industry from educational settings. The fossil fuel industry has used toys and children’s television to normalize their products and manipulate children for decades. Pete Knapp, an ICL alumnus, describes how the construction toy Lego was his childhood obsession, but the pervasive presence of fossil fuel dependency normalized the industry: Many Lego sets were oil tankers, petrol stations, and even oil refineries, and nearly everything in Legoland is reliant on oil. I was totally unaware of this until I started to think about it as an adult. I feel like my creativity was channeled by fossil fuel companies. It made it difficult for me to imagine a world that was not centred around oil. Between 1966 and 1992, both Shell and Exxon were the only companies in Legoland. In 1992, both were replaced by Lego’s own oil company, Octan. In 2009, a wind turbine set was made, still with the fossil fuel company logo on it.11 By presenting Legoland infrastructure restricted to fossil fuels, young people may become less likely to question the role of fossil fuels in society. A lack of imagining alternative ways that society can function may further empower the industry. Fossil fuels may also be presented as a pathway for “progress,” which appears consistently in various forms throughout young age, from cartoons to school textbooks: There were episodes of the Flintstones funded by a fossil fuel thinktank in the 1970s, where Fred wants to join an oil company, or where Fred discovers oil and then brings humanity out of the caves. I was not taught colonial history or the sustainable Indigenous practices and their rich communities, which I believe would have been extremely helpful to learn in school. Instead, I just remember chemistry textbooks talking about how everything was made of oil and how we would be living in the stone age without them. Ian McDermott, an A-Level (age 16-18) teacher of Chemistry, has seen the effect of textbook and syllabus content that favors the fossil fuel industry: Formal delivery of the reality of climate emergency barely features in A-level. The Edexcel Chemistry course I teach specifically excludes climate change. The only mention is in the acid rain section. The Physics and Biology specifications are similarly unhelpful, with no prospect of including the climate emergency in sight. The end of school education in the UK is marked by GCSE exams, which are standardized across five exam boards.12 In theory, this would make it easy to ensure students are educated on how to progress society away from fossil fuels. However, there is currently a significant bias towards presenting fossil fuels as critical for modern life, with the Assessment and Qualifications Alliance (AQA) exam board stating, “many useful materials on which modern life depends are produced by the petrochemical industry, such as solvents, lubricants, polymers, detergents.”13 Similarly, the Oxford, Cambridge, and Royal Society of Arts exam boards ask students to “explain how modern life is crucially dependent upon hydrocarbons.”14 In the United States, with a lack of unity in secondary education, organizations like the American Petroleum Institute and similar state-level organizations lobby against climate education and promote fossil fuel-centered education resources to teachers, leading to some of the highest rates of climate denial in the developed world.15

Cambridge University Press and Assessment claim climate education is “undervalued and underrepresented in the curriculum.” A UK survey found about 35 percent of secondary teachers did not believe they spent enough time teaching it, and about 40 percent of these teachers said they required more resources.16

Fossil fuel companies also take advantage of the unmet needs of teachers at cash-strapped schools. BP, Shell, and others partner with NEED (National Energy Education Development) to provide free educational materials which promote the narratives that fossil fuels are essential. Lesson plans include guidance for making an oil rig using a desk and learning objectives such as “Students will be able to identify and describe careers in the natural gas and energy industries, and list skills and qualifications for each job.”17

Both fossil fuel and meat industries use similar strategies to target children, such as paying TikTok influencers and celebrities to run advertising campaigns.18 Ian feels that young people are left to learn about the climate emergency through social media and finds that high carbon lifestyles are often promoted: Young people are immersed in the 24/7 horrors of social media, where influencers glorify high-carbon lifestyles, and the fossil fuel industry’s manipulative tactics lurk. Often, young people are made to feel guilty for aspiring to such lifestyles, but they are subjected to the most advanced and insidious marketing, and they cannot be blamed. We should certainly not be telling them that it is their duty to fix all the problems that those in power are responsible for now. Though universities are often hubs for innovating cutting-edge climate solutions, they still allow for significant recruitment and messaging from the fossil fuel industry. The industry, therefore, ends up presenting itself as vital and promotes techno-fixes like carbon capture and storage as the solution to the problem. Julia Mitra, an ICL undergraduate in Chemical Engineering, reflects on this: There is no discussion of how carbon capture and storage has been historically used to delay climate action. The message students receive is that both the fossil fuel, carbon capture, and renewable energy sectors are expanding and important. Although we learn about sustainable processes, we’re also equally taught about oil refining and extraction, and there is an absence of any education on why climate change is such a big issue. Even so, a growing number of young people are refusing to work for companies whose environmental values don’t align with their own, a trend known as “climate quitting.”19 In a survey, half of Gen Z employees (ages 22-28) have considered resigning from a job due to a conflict in values, and fossil fuel companies have found that high salaries are not always enough to attract young workers.20

At ICL, companies like BP and Shell have responded to this by providing free services such as CV workshops and hosting careers talks in the opening weeks of the academic year. These companies also donate to the student societies, which allow them to have more frequent and grander pizza nights, sport days, and student activities.21 Sebastian Gonzato, an ICL alumnus and climate quitter himself, said: The industry was everywhere at Imperial College, at the countless careers fairs, careers workshops, guest lectures, event sponsorships, student bursaries, and so on. I would associate them with good times. This is the image they want to present to encourage people to work for them, and to see them as a part of the solution. But it is simply another manipulative tactic that I fell for, along with many others. These companies also target university researchers and lecturers, whose job security and funding are vulnerable. Julia reflected that “Imperial has clung tight to the ‘engagement through investment’ narrative. It has become obvious that the senior management of ICL prefer to work alongside fossil fuel companies rather than to the student body.” Similarly, Sebastian felt that the presence of fossil fuel companies at ICL was pervasive and that this legitimized them: When you’re surrounded by people who are attracted to work with BP to reduce methane leakages, because it feels like you’re being a part of the solution, it is all too easy to start doubting your own sense of urgency and scale of the climate crisis. In my opinion, this influence on university students is the greatest damage that the fossil fuel industry wrecks on higher education. We feel that these narratives are damaging to the mental health of young people, where those who are not convinced by the discourses of the fossil fuel industry are left to feel alienated, gaslit, and disempowered. This may be detrimental to mental health: a study of 10,000 people aged 16-25 across ten countries reported more than 50 percent felt sad, anxious, angry, powerless, helpless, and/or guilty about climate change, and that 75 percent think the future is frightening.22 Additionally, students from low-income backgrounds, who don’t have the luxury of choosing a career based on ethics over salary, are often targeted by the fossil fuel industry or may feel cornered into these jobs. With oil and gas industry workers suffering from poor mental health more than the general population, this trend can further disparities in mental health and burnout rates in disadvantaged students.23 We believe educational institutions hold a responsibility for validating and addressing these emotional responses, and that adopting false narratives are endangering young people’s mental health. Although we focus on ICL in this article, we anticipate the narrative around “working with the industry” presented by places of higher education around the world will be similar, extending to those who work with environmentally damaging industries such as mining, animal agriculture, and fashion. Climate quitting is not limited to young people; fossil fuel workers have also left the industry over ethical objections. In 2022, safety consultant Caroline Dennett left an eleven-year contract with Shell with a resignation video on LinkedIn that has more than 17,000 reactions at the date of writing.24 She has provided quotes for this piece: I severed ties with Shell in 2022 after an Extinction Rebellion protest at the Shell HQ in London encouraged people to jump ship. Organizations and entire industries can change, they do and it’s not always a struggle. One thing is certain: change is only possible if you have leadership. Not because ‘Management’ have all the ideas and answers, but because they have decision-making power and hold the keys to unlock the necessary resources to enable transformation. We also contacted an ex-Shell employee from the research and development branch, Grahame Buss, who takes a less optimistic view: I can tell you this: you cannot change an oil and gas company from the inside. When I joined, my colleagues talked about getting Shell away from oil and gas. When I left 30 years later, Shell was still talking. Unfortunately, that was all it was – talk. When I joined it was an oil company. When I left it was a bigger oil company. A former head of strategy once said to me: “Shell has two drivers: its survival and its profit.” Academic institutions working with fossil fuel companies may also claim, as ICL has, that collaborations with the industry can help to provide them with the tools for a transition to renewable energy.25 Caroline describes how this is not true, in spite of support from staff: Shell was always motivated by oil and gas production; managers are rewarded on this basis. Shell has scaled back their renewable energy efforts, causing the Head of Renewable Generation to leave Shell weeks after the announcement.” 26An open letter written by two employees from their Low Carbon Solutions division of Shell urged the CEO [Weel Sawan] to continue their low carbon investments and practically begged him not to roll-back on their energy transition efforts.27 The letter was seen by 80,000 staff and supported by over 1000 Shell employees. Sawan’s response was to eliminate 200 jobs from the department and review a further 130 positions for redundancy in 2024.28

Within the school environment, Ian McDermott campaigns to change the school curriculum through Extinction Rebellion Educators. Although underfunded schools may be tempted to accept free teaching resources provided by the fossil fuel industry, we argue that this may distract students from the reality of the climate crisis and diminish hope for change. Instead, Ian proposes: We need a planned, cross-curricular, age-appropriate, differentiated, and psychologically-aware curriculum delivered by trained teachers. Our students need totems of success, better storytelling, giving them power over their futures, and the freedom to be teenagers. A strong foundation in climate literacy can increase young people and teachers’ resilience against tactics used by fossil fuel industries. Collecting and sharing examples of resistance like the ones illustrated in this article can then help to empower them. ICA has helped to unite students, staff, and alumni in an environment where siloes are common and detrimental to progress in sustainability. An ICA investigation of fossil fuel sponsorships of student societies was published in the university newspaper, showing great financial contributions to groups such as the Chemical Engineering Society, which is an important avenue for students’ job searches and engagement.29 This led to the student union legislating to “strive to not have relationships with third parties directly involved in the… production of fossil fuels; strong affiliations with producers of fossil fuels; and production of significant greenhouse gas emissions with no strategy for Net Zero.”30 ICA also worked with the university management to encourage and provide funding for sustainable travel to conferences (e.g. by train rather than plane).31 Disruptive action has also had a place in enacting necessary change: ICA’s threat to disrupt a career fair led to Schlumberger pulling out. However, despite many meetings with ICL’s careers service, they advertise jobs explicitly for “Extraction of Oil & Gas,” demonstrating that much more work needs to be done.32

National campaign groups, such as People & Planet in the UK, have coordinated efforts to ban fossil fuel companies from careers fairs, with a 30 percent increase from 2023 to 2024.33 ICL has adopted the strategy of supplementing career offerings with Green Careers Fairs, hosted in collaboration with sustainable societies like ICA. They have been very successful, with twenty-seven companies and more than 500 attendees, demonstrating the student body’s interest in careers with sustainably minded companies, and the impact that career fairs have on which opportunities students are able to pursue.34 Great consideration is, however, required to maintain the integrity of these spaces and avoid opening it to greenwashing. According to the latest annual sustainability and ethics survey in higher education, institutions blocking fossil fuel companies from graduate recruitment events increased by 30 percent in 2024.35

ICA also works to unite societies and strengthen voices that are otherwise siloed and easily dismissed. We argue that direct action is the fastest way to create change, but should be undertaken with great care to anonymize individuals or to work in groups to avoid individuals being targeted. We believe that student voices are not given the prominence at universities they deserve, where universities are treated as businesses with students as tools. Universities should be for students, rather than students being for universities. Sharing best practices, experiences, success stories, and struggles can also strengthen the movement to cut ties between education and fossil fuels. Efforts to unify UK climate action groups between universities, and with local climate action groups, is underway through new organizations such as the Education Climate Coalition.36

Producing reports or organizing protests that put pressure on breaking apart collaborations with bad actors may be more successful with local or national press coverage but require careful consideration of a clear and concise message and its presentation. So far, the strategies in education adopted by the fossil fuel industry have been successful, although we are now seeing this begin to break down due to collective awareness and action. We hope that this article will provide more momentum to cut ties between this industry and educational settings and inspire radical action toward nature-based solutions, reduced consumption, active travel, equity, empowerment, and collaborative community at the center of education. Imperial Climate Action are a campaign group at Imperial College in London. Our groups focuses on cutting ties between academia and weapons, mining, and fossil fuels; plant-based diets; decolonising academia; reducing aviation; empowering activists; cleaning up careers fairs and research funding; and telling the truth about the scale and urgency of the climate and nature emergencies to students and staff.

Ages 4–12: Toys & Television

Ages 12–18: School

Ages 18–26: University

Age 26–Retirement: Working with Fossil Fuel Companies

Case Studies of Climate Action Groups

—

More articles in Rethinking Science Communication will be posted over the next month. Subscribe/purchase this issue to read it today.

Notes

“Nigeria: Shell Complicit in the Arbitrary Executions of Ogoni Nine as Writ Served in Dutch Court,” Amnesty International, June 29, 2017, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2017/06/shell-complicit-arbitrary-executions-ogoni-nine-writ-dutch-court/.