Chinese Medicine: A Framework for Healing and Liberation

By Gwen D’Arcangelis

Volume 26, no. 2, Ways of Knowing

A little-known fact of the vibrant 60s/70s era in the US is the role that Chinese medicine played in health programs of New York City’s Black and Puerto Rican liberation groups and the Berkeley, California-based Asian American Political Alliance. These groups, emerging from communities targeted and neglected by the state, formed their own programs, from liberation schools to health care clinics. They were particularly inspired by health initiatives that were part of the social revolution in China led by Mao Zedong, to bring health care to underserved rural communities by training farmers to be amateur practitioners known as “barefoot doctors” [赤脚医生]. The program gained international attention and, alongside Mao’s rhetoric about the value of Chinese medicine, caught the ears of US liberation activists.

Groups on the east coast focused on learning and applying acupuncture for opioid withdrawal—a problem driven by the state neglect and poverty that communities of color faced.1 The west coast groups turned to the cultural, alongside medical, utility of Chinese medicine. Chinese American activists found pride in these medicinal traditions in the face of ongoing discrimination and the white Western devaluing of Chinese culture, science, and medicine. As activist and martial artist Sifu Bryant Fong recalls:

[Chinese medicine] was important because we did see it as part of ourselves. It was part of our culture—one way of healing that Western medicine or Western science didn’t think was valid, and we felt it was something that we could contribute that would be different from what they’re doing and actually could have some real effect. Making contact with China allowed us to see that that was really true. And so it became part of the Asian movement.2

Chinese medicine had a steady presence in the US since the arrival of Chinese immigrants in the nineteenth century, but it was legalized only in the 1970s. Thus it remained hard to access, even among Chinese Americans. With Mao’s encouragement, these activists looked more deeply into the underground network of practitioners, revealing and reconnecting with the vast knowledge base of Chinese medical therapies: from acupuncture [針灸] to herbal medicine [中藥], tuina [推拿] therapeutic massage, bone setting [跌打], and the physical movements of qigong [氣功].

This resistance to cultural imperialism has blossomed in full force within many of today’s movements. In the mid-2000s, queer BIPOC feminist organizers coined the healing justice framework to underscore the deep impacts that oppression has on the bodies and health of Indigenous, Black, and other People of Color communities. It also centers the need for healing in movements organizing for liberation—from disability justice and reproductive justice to myriad other feminist, queer, and abolitionist struggles.3 Organizers have dismissed the myth of Western cultural superiority in their recovery and recognition of valuable medical and healing knowledge engendered within our own BIPOC traditions. Chinese medicine, with its potent treatments and bevy of lay practices, now holds a prominent place in movement work.

Inevitably, activist-practitioners contribute to an evolution of practices as they draw out features of Chinese medical therapies. The context-dependent orientation lends itself to an adaptability over time and place. Chinese medicine is in fact a rubric denoting diverse systems, including a multitude of regional lineages and family traditions, some dating back thousands of years. In China, the state periodically reconciled these heterogeneous styles, consolidated in recent times under Mao’s selective assemblage institutionalized as “Traditional Chinese Medicine” (TCM).4 Although some styles were stamped out, more persisted or transformed as ideas traveled in China and elsewhere. Where TCM became the primary style taught in schools, including in the US, Chinese medicine doctors continue to practice and teach styles that predate TCM.

In what follows, I aim to demonstrate the importance of Chinese medical “ways of knowing” for healing and liberation, and in the process challenge dominant Eurocentric notions of science, medicine, and expertise. Through snapshots of US activist-practitioners garnered from both my ethnographic and activist work, I showcase specific therapies and their underlying Chinese philosopho-medical concepts such as qi [氣] and self-healing. We have much to learn—in our communities and in our movements—from this mobilization of Chinese medicine for liberatory healing.

Cultivating Amateur Expertise

While the role of the well-trained expert remains esteemed in Chinese medicine, its appeal for social movements has always been the gamut of non-expert practices. Amateur expertise provided the cornerstone to China’s barefoot doctors program in the Maoist era, and provided the foundation for 60s movement groups in the US.5 These groups initially paid attention to Chinese medicine because Mao uplifted it as symbolic of China’s strength and autonomy in the face of Western imperialism, countering Western hegemony on scientific knowledge and medicine. Young Lord Dr. Walter Bosque, who co-founded the Bronx-based Lincoln Detox School of Acupuncture in 1974 with the late Black liberation activist Dr. Mutulu Shakur, explained: “One of the things that Mao said [was] that traditional Chinese medicine was the treasure of Chinese culture and that everyone should look at it. So when he said that, we started looking.”6

In their study sessions, Bosque, Shakur, and fellow activists uncovered an ear acupuncture protocol used in Hong Kong and Thailand for drug detoxification.7 Activists recognized the parallels between China’s earlier opium epidemic (the result of Western imperialism) and the heroin epidemic in Puerto Rican and Black communities in New York City (the result of state neglect and targeting of communities of color). Acupuncture could replace the state’s biomedicalized approach of substituting one opioid (methadone) for another (heroin). Highly addictive, methadone also required registration at state-run hospitals, which enabled further surveillance of communities of color.

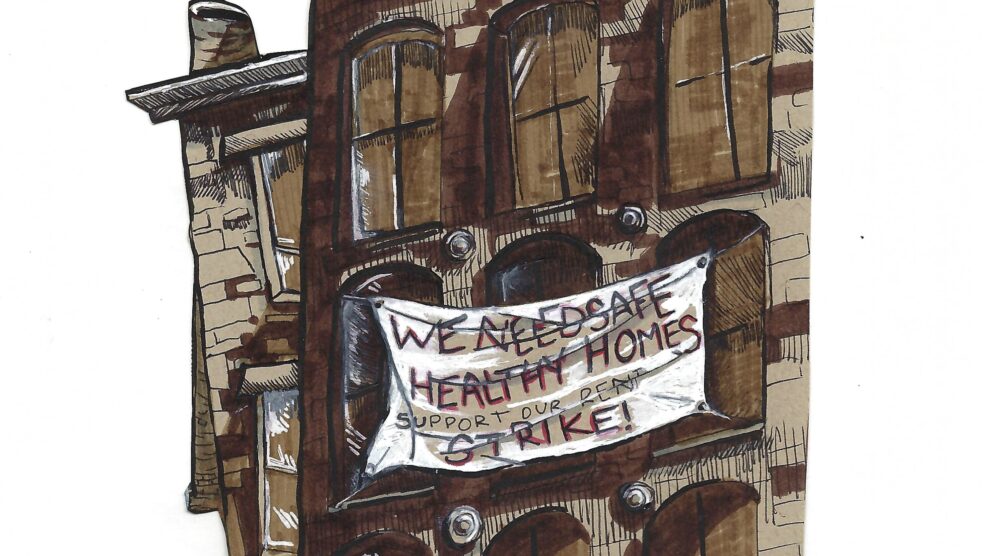

The Young Lords and Black liberation activists strengthened the tether between Chinese medicine and accessible healing by valorizing amateur expertise, providing viable alternatives to communities that are socially or structurally disenfranchised from accessing conventional healthcare.

Through training with acupuncturists, visits to Chinatown, and their own experiments, liberation activists led by Shakur and Walter Bosque developed and refined a simple five-point needling technique on the ear. Later coined the NADA (National Acupuncture Detoxification Association) Protocol, the procedure required only a few weeks of training—making it easily taught and shared within a community. Many recipients of the NADA Protocol could be trained, perpetuating knowledge as NADA practitioners themselves.8 This horizontal sharing of knowledge between patient and practitioner expanded access to health care and generated community practices and autonomy from a punitive state.

The Young Lords and Black liberation activists, in adapting medical knowledge to their local contexts, produced a versatile treatment in the NADA protocol, which is now used worldwide for many types of trauma.9 Further, they strengthened the tether between Chinese medicine and accessible healing by valorizing amateur expertise, providing viable alternatives to communities that are socially or structurally disenfranchised from accessing conventional healthcare. For patients of color––as well as women, trans, and disabled patients–amateur techniques offer health autonomy in the face of rampant social inequalities and hierarchies.

Food, Qigong, and Collective Healing

Unlike in the 1960s, US activist-practitioners today can draw from a fuller repertoire of Chinese medical therapies. Whether emerging from Chinese community lineages, US schools, or a combination of the two, Chinese medicine doctors in the US can practice freely and train others in a diverse set of systems, albeit constrained by biomedical hegemony and the dominance of TCM. Many continue to foreground lay practices in movement work, lending their expertise to the transformation of complex modalities into accessible practices.

Wendy* is a practitioner of herbal medicine and longtime racial justice organizer who develops medicinal food therapy for wide dissemination. Food medicine is a close relative of herbal medicine, the most complex of Chinese medical modalities, which requires an expert combination of ingredients that must complement each other as well as the patient’s constitution and environmental context. Medicinal food therapy, while less complex, draws on the energetic properties of foods, combining them in ways that are nutritional, tasty, and efficacious. Wendy creates simple recipes based in her own Chinese cuisine, for example sugar snap peas or green beans for hives or eczema; or dishes with garlic for its antibacterial and digestive properties; and tofu to fight congestion and constipation. Wendy tailors dietary recommendations for foods that are available and familiar to people, making medicinal food therapy accessible. As a layperson with my own Chinese family food medicine traditions, I have incorporated Wendy’s recipes into my cooking and expanded my knowledge of food medicine. An excellent vehicle for delivering contextualized medicine, any cuisine can be made into food medicine by considering Chinese medicine principles and properties of relevant foods.

Today, Chinese medicine, alongside other BIPOC medical traditions, attends to the spiritual together with the social, physical, emotional, and psychological factors, as an increasingly popular antidote for trauma-informed BIPOC movements.

Effective lay practice must consider local context as well as the nature of self-healing—a core principle in Chinese medicine. Deriving from a Daoist philosopho-medical view that sees the human body as a microcosm of the larger universe and characterized by its own rhythms, Chinese medicine harnesses the body’s intrinsic healing capacities.10 The practitioners I’ve conversed with characterize their job as one of facilitation—to activate the dynamic processes of the human body and help it reset. Acupuncture illustrates this relationship very well: needling functions to stimulate qi [氣], loosely described as the vital force or energy underlying all existence, at points where it is blocked along meridian channels. The state and circulation of one’s qi are paramount to good health. Practitioners highlight, for example, “Your bodies are wise . . . are in tune with nature, and that is wisdom. The [acupuncture] needles are just my reminder of what your body already knows anyway.” “It’s not my qi that’s healing someone else; it’s their own qi.” This focus allows activist-practitioners to train communities in practices that can be easily practiced on oneself. One widespread self-driven healing practice is qigong, consisting of basic movements to cultivate body, mind, and spirit. The goal is to move qi within the body in relation to the wider universe, and in the process develop an awareness of the body’s healing processes. While some qigong exercises necessitate continual guidance from a teacher, others can be practiced independently after a single training. Jo,* who expanded their qigong practice during the isolation of the early COVID-19 period, describes the importance of qigong as a pathway to community healing, to “make you not only just have a moment of quiet and hopefully peace, but also make you feel more connected to the universe and connected to each other.”

The power of qigong to forge connections is particularly important for many of us in queer, trans, and disabled communities who face isolation even in non-pandemic times. Like food medicine, lay qigong exercises can provide sustained vehicles for self- and collective healing.

Trauma and Spirit

Trauma undergirds most deleterious health conditions wrought by systemic oppression. As healing justice organizers Cara Page and Erica Woodland explain, trauma is “not the experience per se but our physical, emotional, spiritual, and psychic responses to that experience, which are shaped by our lived experiences of intergenerational trauma and structural violence.”11 US Indigenous and Black feminist health movements have focused on trauma since at least the 70s, when activists began turning away from biomedical traditions and their mechanistic understandings of body/mind separation. Instead, they sought alternatives in their own traditions that could address and alleviate trauma in all its complexity. Today, Chinese medicine, alongside other BIPOC medical traditions, attends to the spiritual together with the social, physical, emotional, and psychological factors, as an increasingly popular antidote for trauma-informed BIPOC movements.

In Chinese medicine and philosophy, shen [神], loosely translated as spirit, is what animates humans and connects us to the cosmos.12 The dimensions of illness involving shen are not wholly separable from other elements—physical, emotional, and psychological. In fact, Chinese medicine rests on the principle that healing encompasses all of these elements. Moreover, specific protocols in Chinese medicine incorporate ritual or treat primarily spiritual conditions. Many of these are found in the “Classical Chinese Medicine” (CCM) traditions. These lineages are rooted in texts known as the “Classics” dating back thousands of years. CCM contrasts with TCM, the Mao-era codification of a once vibrant system of innumerable lineages—what was for some too heterogeneous—into something more cohesive and standardized. Notably, in the process of producing TCM, Mao ejected spiritual aspects to make Chinese medicine more comparable to Western biomedicine (part of the Mao-era project of achieving modernization and leaving behind “feudal superstitions”).13 This was deeply ironic in that Mao’s very uplift of Chinese medicine represented a rejection of Western hegemony.

But in fact, the spiritual elements survived—in lineages in China, the diaspora, and other locales where classical traditions persisted. Qigong, for instance, is a physio-spiritual modality. Even TCM itself could not be wholly purged of spiritual elements, retaining treatments for psychological-spiritual conditions based on a set of channels known as the Eight Extraordinary Meridians [奇經八脈].

In the US, one popular acupuncture style is based on the “Five Elements [五行],” a classical theory with a robust focus on the spiritual aspects of illness and healing.14 Tina* introduced me to the use of a Five Elements style of acupuncture to “treat the spiritual-psychological-emotional issues that . . . people of color [face].” Tina explained how needling the point yintang [印堂], located between the eyebrows, can help to interrupt the effects of stress and its cascade of deleterious effects on the body. This acupuncture treatment restores the body to a state where it can begin healing, what Tina describes as “pulling the body down and into rest and repair.” Moreover, Tina highlights that Chinese medicine is ideal for addressing the continual onslaught of systemic stressors that Black and other POC and Indigenous communities face, wherein “higher brain functions go offline when you’re in this [stress] state. . . . freaking out about the fact that I live in a food desert . . . that there goes the cops again, I think they’re following me home.” The toll systemic oppression takes—emotional, spiritual, and physical—can be mitigated, ending intra- and inter-generational harm.

Whether it be acupuncture styles derived from the Five Elements tradition, the NADA protocol generated in the last century, or the spiritual treatments derived from the oldest of lineages, Chinese medicine approaches are able to treat the multi-dimensionality of trauma. Healing trauma–especially doing so intergenerationally–is key to our communities and movements if we are to survive to fight another day.

Towards Liberatory Healing

As we continue to build a vibrant mosaic of medical systems, my meditation on Chinese medicine foregrounds its importance as a system with a breadth of modalities and treatment approaches for our current contexts in the US. It offers an abundance of practices that can be easily shared among and adapted to our communities; paradigms that can integrate the physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual aspects of health and illness; and modes of healing that promote autonomy alongside interconnection. With our attention turned towards the ways activist-practitioners have amplified these aspects of Chinese medicine, we get closer to the collective healing that our movements—feminist, abolitionist, socialist—seek.

*Names have been changed.

Meet the contributors:

Gwen Shuni D’Arcangelis (Ph.D): Gwen Shuni D’Arcangelis is associate professor of Gender Studies at Skidmore College. Her writing centers on the socio-political dimensions of science, medicine, and public health. D’Arcangelis also engages in community-based work on science and health justice.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/gwen.darcangelis/

Twitter, Instagram: @darcangelgwen

Cori Nakamura Lin: Cori Nakamura Lin is descended from East Asian island peoples, and was born and raised in the midwest. Her art has been published in the LA Times, Eater Chicago, WBEZ Chicago, PBS Channel Learning Media, and has been featured on the History Channel.

Instagram: @onibaba.studio

Website: www.onibaba.studio

Notes

- Mia Donovan, dir., Dope Is Death (Montréal: EyeSteel Productions, 2020)

- . Bryant Fong, interview by Gwen D’Arcangelis, September 29, 2022.

- Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, “A Not-So-Brief Personal History of the Healing Justice Movement, 2010–2016,” MICE Magazine, October 20, 2016; Cara Page and Erica Woodland, Healing Justice Lineages: Dreaming at the Crossroads of Liberation, Collective Care, and Safety (Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 2023).

- Elisabeth Hsu, The Transmission of Chinese Medicine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- Lan Angela Li, “The Edge of Expertise: Representing Barefoot Doctors in Cultural Revolution China,” Endeavour 39, no. 3–4 (2015): 162; Alondra Nelson, “Origins of Black Panther Party Health Activism,” in Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 49–74.

- Walter Bosque, interview by Gwen D’Arcangelis, September 7, 2022.

- NADA, “NADA Full Circle Part 3,” (presentation, NADA Full Circle: Looking Back into the Future conference, 2021).

- NADA, “NADA Full Circle Part 3.”

- Eana Meng, “‘It’s First Aid!’: Tracing the Global Transmission of a Five-Point Ear Acupuncture Treatment,” Harvard University Asia Center, September 14, 2020, YouTube video, 29:09.

- Robin R. Wang, “Yinyang Body: Cultivation and Transformation,” in Yinyang: The Way of Heaven and Earth in Chinese Thought and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 175–79.

- Page and Woodland, Healing Justice Lineages, 8–9.

- Wang, “Yinyang Body,” 187–89.

- Dominic Steavu, “Delocalizing Illness: Healing and the State in Chinese Medicine,” in The Law of Possession: Ritual, Healing, and the Secular State, ed. William S. Sax and Helene Basu (Oxford University Press, 2016), 82–113.

- Tyler Phan, “American Chinese Medicine” (doctoral thesis, University College London, 2017)