Sequencing Revolt: How Grandmothers Fought the Argentinian Military Dictatorship and Revolutionized Science

By Camila Valle

Volume 26, no. 1, Gender: Beyond Binaries

“They’re a married couple who never had children, she wasn’t pregnant as far as I know, and now all of a sudden there’s a baby,” someone tells them in a hushed voice.

It was 1979, three years since the beginning of the Argentinian military dictatorship and two years since the mothers and grandmothers of those disappeared by the regime began regularly marching, one after the other, around the perimeter of Plaza de Mayo, the central square in Buenos Aires. They wore white pañuelos, or handkerchiefs, around their heads and defied the ban on public assembly every Thursday to demand information about and the safe return of their loved ones.

The dictatorship in Argentina—one of the cruelest and bloodiest in the region—was in full swing. Around thirty thousand people were taken from their homes, universities, workplaces, off the streets and buses, to concentration camps to be tortured and murdered. In what came to be known as death flights, many were drugged, stripped, loaded into planes and helicopters, and dropped into bodies of water. The terror of the state loomed everywhere.

Among the disappeared were an estimated five hundred babies and children, either taken along with their parents or born in the camps under brutal, inhumane conditions1. Pregnant people who were taken were tortured, subjected to horrifying conditions including unsanitary cells and poor nutrition, and forced to give birth in shackles. For the most part, the military waited until they gave birth to kill them. “Subversive parents teach their children subversion,” warned former Buenos Aires police chief General Ramon Campos in a 1984 interview.2

Since there were no personnel at the military facilities to deliver babies, doctors and midwives would be kidnapped off the street, blindfoded, and taken to someone in labor. They were instructed not to speak and to deliver the child alive. And yet, over the course of hours of labor, words managed to slip through in whispers despite the presence of guards, and many young mothers were able to pass along their names, often as a last act of defiance. Most midwives relayed the information to the grandmothers, and at least one was disappeared for her divulgence. The children were then illegally handed over to families of the regime, adoption agencies, orphanages, or sold in underground markets; doctors were ordered to falsify birth, medical, and death records.3

The mothers and grandmothers of the kidnapped—who eventually became a formal organization, the Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo—did anything they could to track down their grandchildren. They followed faces and word of mouth, gathered intel from neighbors about couples and military families, recorded calls from school secretaries who reported fraudulent birth certificates used for enrollment, scrutinized hospital and adoption records, even secured jobs as domestic workers to enter the homes of military families.4 They filled hundreds of notebooks and binders. At one point, they created a form for all the grandmothers to fill out, trying to collect and systematize as much information as possible about the grandchildren and their parents: blood type, hobbies, likes and dislikes, physical markers such as eye color and hair texture, and so on.

“More than once, I followed women who were carrying babies in their arms that looked like one of my children. At the time, I didn’t even know if I had a grandson or a granddaughter, but I remember following a woman once and then, when she was in front of me, looking at her face and the face of her baby and they were the same—she was clearly the mother. . . . We just didn’t have any other recourse,” remembers Estela Carlotto, president of the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo. Her daughter, Laura Estela Carlotto, had been taken pregnant in 1977. A former cellmate remembers that on August 25, 1978, as she was being led away to be shot, Laura declared, “My mother will never forgive them.” Her son Ignacio was found in 2014.5

As the grandmothers organized together in search of their grandchildren, concrete questions emerged: How long does it take a vaccine scar to fade away?6 A birthmark? Some had held onto locks of hair or baby teeth for years—could they be of any use? And what about the babies born in captivity, whom they had never known?

In March 1980, the grandmothers found sisters Tatiana Ruarte Britos and Malena Jotar Britos. Yet, when they came forward to demand their safe return, the photographs, anecdotes, and other mementos they had collected proved insufficient to win a legal battle. The grandmothers quickly realized that finding the children was only the first step; what they needed now was a foolproof method of identification.

In Search of Science

Several months earlier, in 1979, an article had come out in the newspaper El Día about a man obliged to take a paternity test via blood sample after denying that he was the father of a child (the paternity test came back positive). A lightbulb went off: Could the grandmothers’ blood be the key? Up until then, as in the case of the reported paternity test, scientists had figured out how to determine biological ties if the blood of a child and their parents were available, but what happens if the parents are not there? How do you establish, with overwhelming certainty, biological filiation if there is a generational gap in data?

They asked questions, remained curious and insatiable […] even when acclaimed institutions told them something was impossible

In 1982, with the dictatorship weakened by the defeat in the War of the Malvinas (Falklands War), the grandmothers traveled abroad looking for answers. They visited twelve different countries and met with doctors, chemists, biologists, human rights organizations, anyone they could think of. They all told them, “No, there’s no such thing as what you’re looking for.” But the grandmothers were becoming grassroots scientists: they asked questions, remained curious and insatiable, hypothesized, studied, tested, tried, learned and relearned, even when prestigious, internationally acclaimed institutions and specialists told them something was impossible.

In November of that year, the grandmothers flew to Washington DC to take part in the General Assembly of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States. There, Isabel Mignone—sister of Mónica Mignone, who was taken in 1976—put them in touch with Víctor Penchaszadeh, an Argentinian geneticist and doctor who had gone into exile after narrowly escaping a sequestering attempt by the dictatorship.

What the grandmothers were trying to do was unprecedented and Penchaszadeh was the first to give them any leads. He explained that they could likely get somewhere by comparing molecules in blood samples, but the more distantly people were related, the less efficacious the samples would be. Penchaszadeh proved vital. He connected the grandmothers with a number of specialists, most of them US scientists and exiled Argentinian and Chilean scientists, who agreed to help them undertake the necessary research and study.7

Grandmother Nélida Navajas remembers their meeting with Fred Allen, director of the New York Blood Center: “He saw that we were so desperate that he said, ‘Give me time, I’ll take care of it, we’ll be able to do something.’” He served them coffee, began doing calculations, and concluded that they would have to try to adapt the statistical-mathematical formulas used in paternity tests. It would require a tremendous amount of work, but it was theoretically possible.8

Penchaszadeh, Allen, Pierre Darlu, epidemiological geneticist Mary-Claire King, and one of King’s professors, Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, began working together in the United States to transform the standard probability of the traditional paternity test into one that would work when parents were missing. After a year of work, in October 1983, the same month the dictatorship fell in Argentina, the grandmothers got a call from Chilean biochemist Cristián Orrego to let them know that their scientific investigation would be on the agenda of the May 1984 symposium of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in New York. “Can we go?” the grandmothers asked. Orrego responded: “You’re the ones who developed this research. How could you not go? Of course you have to go! I want you to tell your stories there; they are what ultimately give this discovery value.”9

At the time, scientists didn’t sequence DNA because the technology to do so didn’t yet exist. But they did study genetic products, including histocompatibility antigens on the cell surface, which were used to determine “matches” for transplants. Just as Allen had predicted, it was possible to establish biological links between grandparents and their grandchildren through the analysis of distinct genetic markers. As Navajas explains, “The dad and the mom weren’t there, but the child was, as were the grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins. . . . A grandparent might be missing but there were uncles, aunts, siblings. The more blood that could be obtained, the better.”

It would still be some time before we arrived at the knowledge about genes and DNA that we have now, and before the corresponding methods of identification were developed, but the biggest scientific leap had been made—all thanks to the activist work of the grandmothers. The next step was to take it to Argentina and carry out a political process.

The Case of Paula Eva Logares

It would be a mistake to situate the grandmothers’ fight within a framework of biological determinism, conflating identity—even biological identity—with genetic data. The grandmothers understood from the beginning that genetics would not just restore individual identities, but would also connect people to their family, social, and political histories—the histories and memories of an entire generation the state tried to annihilate. And in doing so, the grandmothers reimagined a different relationship between science and society; not a science for profit or oppression, but a people’s science that emerges out of concrete conditions of struggle—a science of love. As Evel “Beba” de Petrini, mother of Osvaldo Sergio Petrini, disappeared at twenty-one, remarked: “We are everyone’s mothers; we socialized maternity.” One of the grandmothers’ slogans sums it up neatly: “They are all my children.”10

After the fall of the dictatorship, driven in large part by the mothers and grandmothers, the government established the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons to investigate the human rights abuses and what had happened to the disappeared. René Favaloro, doctor and member of the commission, suggested that the grandmothers team up with the doctors Emilio Haas y Luis Verruno in their search for their grandchildren. “They apparently had all the equipment, the tools, the know-how,” remembers Carlotto. “But of course we did our research and found out that Verruno . . . worked for the military hospital. We contested it.”

All of the scientists who were offering to help the grandmothers test their genetic identification theory had deep ties to the dictatorship. It was proving almost impossible to find someone who had not collaborated with the regime, until they found doctor Ana María Di Lonardo, chief of the immunology department at Durand Hospital in Buenos Aires, who had a fully equipped lab to do the work. Shortly after, King and Di Lonardo successfully ran the first histocompatibility antigen tests, trying it out on two grandmothers and a granddaughter who had not been kidnapped.

The grandmothers reimagined a different relationship between science and society […] a people’s science that emerges out of concrete conditions of struggle

In July 1978, Elsa Pavón de Aguilar quit her job and began searching for her daughter Mónica Sofía Grinspon and granddaughter Paula Eva Logares, who were disappeared together a couple months prior. On a trip to Brazil, the grandmothers received a photograph of a child. It was, unmistakably, Paula. She was living as the daughter of Rubén Lavallén, the deputy commissioner of the Buenos Aires Province Police, under the name Paula Lavallén and an incorrect birth year: 1978 instead of 1976. As soon as the grandmothers found the home address, Aguilar began to travel to the neighborhood to catch a glimpse of her from afar. Finally, on one of the visits, Aguilar saw and recognized her granddaughter immediately. Paula was coming home from school, dressed in a kindergarten uniform, even though she was supposed to be in elementary school.

In December 1983, on the first official business day since the return of democracy, Aguilar filed a report in federal court. But Paula had a government-issued ID, which meant the grandmothers had to prove that her identity was fake. The grandmothers had received blood samples from Mónica Grinspon’s brothers, sister, and mother, and Claudio Logares’s (Paula’s father) parents, and the court ordered a blood test for Paula. King and the team at Durand Hospital ran all the tests and the results were in: Paula was almost certainly a Grinspon-Logares. The judge accepted the evidence but denied Paula’s restitution, siding with Lavallén, who argued that to rip Paula from the home of the “only family she had ever known” would be even more traumatic. The grandmothers appealed to the Supreme Court, won, and in December 1984 Paula was returned to her grandparents. When Paula entered the house for the first time since her disappearance, she walked straight to what had been her room, opened the door, looked at the bed, and asked: “Where’s my teddy bear?”11

Institutionalizing the Work

Now that the science had been tested successfully, the grandmothers’ main concern was judges’ acceptance of the genetic testing as evidence. Carlotto noted: “Eighty percent of the judges came from the dictatorship and we had already had serious issues with them. There was absolutely no way to work with the Justice at the time, just no way. . . . A law was indispensable.”

In February 1986, the grandmothers met with president Raúl Alfonsín with four demands, including that he present a bill to Parliament that would give legal validity to the genetic analyses conducted at the Durand Hospital and that would establish a National Bank of Genetic Data (BNDG, its acronym in Spanish). In 1987, the bill was passed unanimously. The law specified that: the bank’s services would be free for family members of the disappeared; courts would order genetic studies in all cases regarding children with dubious biological ties, even if people involved were living abroad; any refusal to undergo testing would be considered a sign of complicity in the kidnappings; and the bank would keep all samples until at least 2050. The BNDG guaranteed that samples were taken, stored, analyzed, categorized, and labeled properly. It was the first instance of a state successfully creating a tool for reparations for crimes perpetrated by the state itself.

In September 1987, King worked on the case of a girl who had been born in the camps and stolen by a police couple. The blood tests were enough to find the child’s true identity, but it had been a difficult case because the only living relative was the child’s maternal grandmother. “Immediately, the question was raised of what we would do with a family with very few living relatives,” explains King. Coupled with issues of the freshness of blood samples and how many families needed to be tested, it was clear that there were new scientific problems to resolve. They needed more genetic information.

During discussions over these emerging questions, King lovingly recalls that the grandmothers hugged her, served her sandwiches and a strong cup of tea (“stronger than an American could have imagined”), and said, “Go back to Berkeley, dear, and give us a call in a couple of weeks when you’ve figured it out.”12

Back at Berkeley, King concluded through various tests and research that identification through mitochondrial DNA via the newly developed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests could be the key. The lab of Allan Wilson, one of King’s mentors, was working on PCR studies of mitochondrial DNA at the time and had developed fast, safe methods to directly sequence genetic material. King knew that they had to avoid erroneous identifications at all costs, and “mitochondrial DNA presented the unbeatable convergence of three pieces of biology and technology: a purely maternal molecule, so that any maternal relative could substitute for any other maternal relative; extraordinary levels of genetic variation; and simple direct sequencing.” Months later, King and the grandmothers would conduct the first identification through mitochondrial DNA. The grandmothers liked to say that it proved God is a woman because she put mitochondrial DNA on earth specifically for their use.13

By the early 1990s, it was clear that all the different vectors of analysis had to be used together, not substituting certain methods for others, combining the study of both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA (including Y chromosomes), and histocompatibility.

In this spirit, in 1991 the grandmothers began building a bank of mitochondrial DNA in King’s lab in the United States. In March of that year, the police had raided the BNDG and taken blood samples, convincing the grandmothers that they needed backup data. The new samples were taken in the office of the grandmothers, refrigerated, and taken to the United States whenever scientists like King and Penchaszadeh traveled between the two countries. In cases where there were doubts and access to the maternal genetic lineage would be useful, the grandmothers requested King’s lab to run tests on samples stored there.

The grandmothers traveled around Argentina for new samples for the bank. “It was a moment of encounter and that was what mobilized people, seeing faces more than offering an arm for blood,” recounts Mario Vinocur, a medical student and former activist of the Intransigent Party who started working with the grandmothers. In addition to collecting mitochondrial DNA, the grandmothers began building databases of family trees and information, such as the dates of every blood sample and how many blood samples specific relatives had provided. Later that year, the BNDG established its own section of mitochondrial DNA.

In 1992, the grandmothers successfully urged the government to create the National Commission for the Right to Identity within the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights to help find the children taken during the dictatorship. The commission’s functions included soliciting documentation from every place that took part or intervened in the recording of babies born between 1975 and 1981; ordering blood tests at the Durand Hospital; and aiding the BNDG, such as making sure that it received the necessary resources and equipment. The commission became another interlocutor for people who had doubts about their identities, and proved instrumental in sustaining the BNDG.

The BNDG will exist as long as a single grandchild remains missing and unaccounted for. Even if that grandchild grows old, dies, there will still be their children, their relatives, their children’s children, who will eventually find out that their parents or grandparents or uncles or aunts or cousins were victims of the dictatorship. They may want to know, and they will have the right to know.

Though the arduous arrival at the index of grandparentness was a scientific one, it was also a political struggle. It was not simply a question of producing scientifically valid data, it was a question of fighting for it to be socially meaningful. That genetics—a field with a past and a present indelibly tied to racism, oppression, a eugenics movement involving immense violations of reproductive rights, and genocide—could be used for human dignity instead of against it, was a watershed moment. The grandmothers went on to share their knowledge with other victims of state terrorism and their loved ones in other parts of the world, such as El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Rwanda, Mexico, Chile, Honduras, and the Philippines.

In their decades of work, research, and study, in their fight against the state, the grandmothers themselves became scientists, beyond and against mainstream notions of what it means to be an “expert.” Emma Baamonde recalls how they began the search: “We worked like ants, we worked like spies. Nobody trained us. We learned everything by ourselves.”14 It was an exigence borne out of conditions of struggle. And they changed science as we know it.

Today

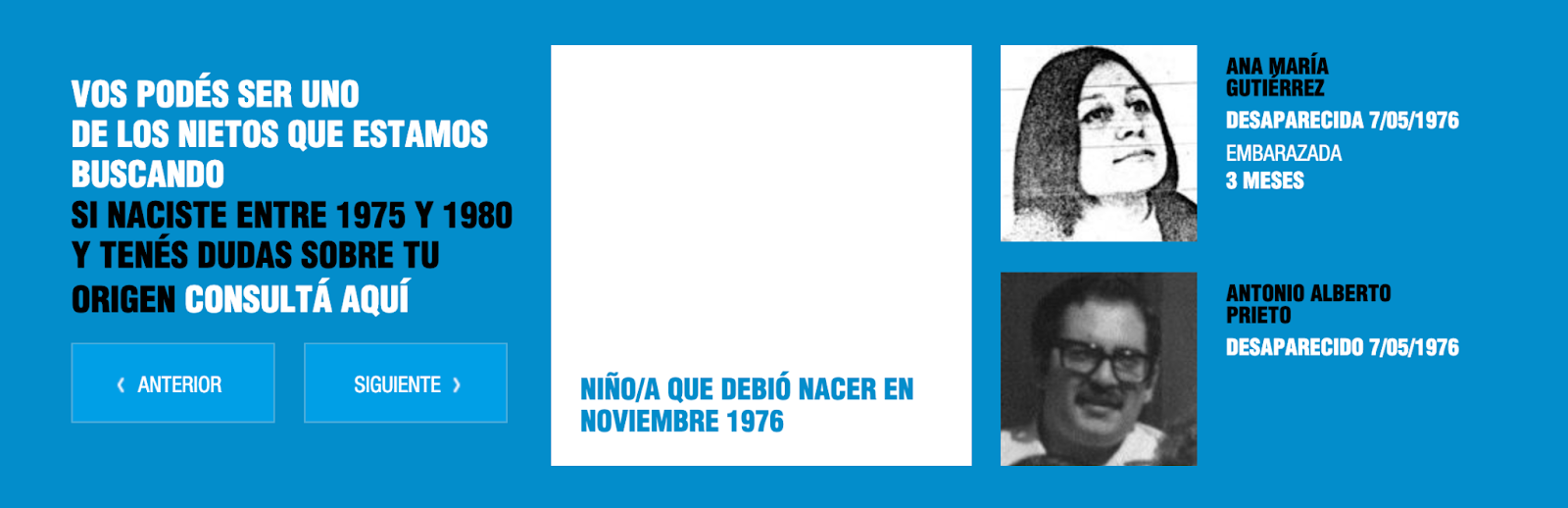

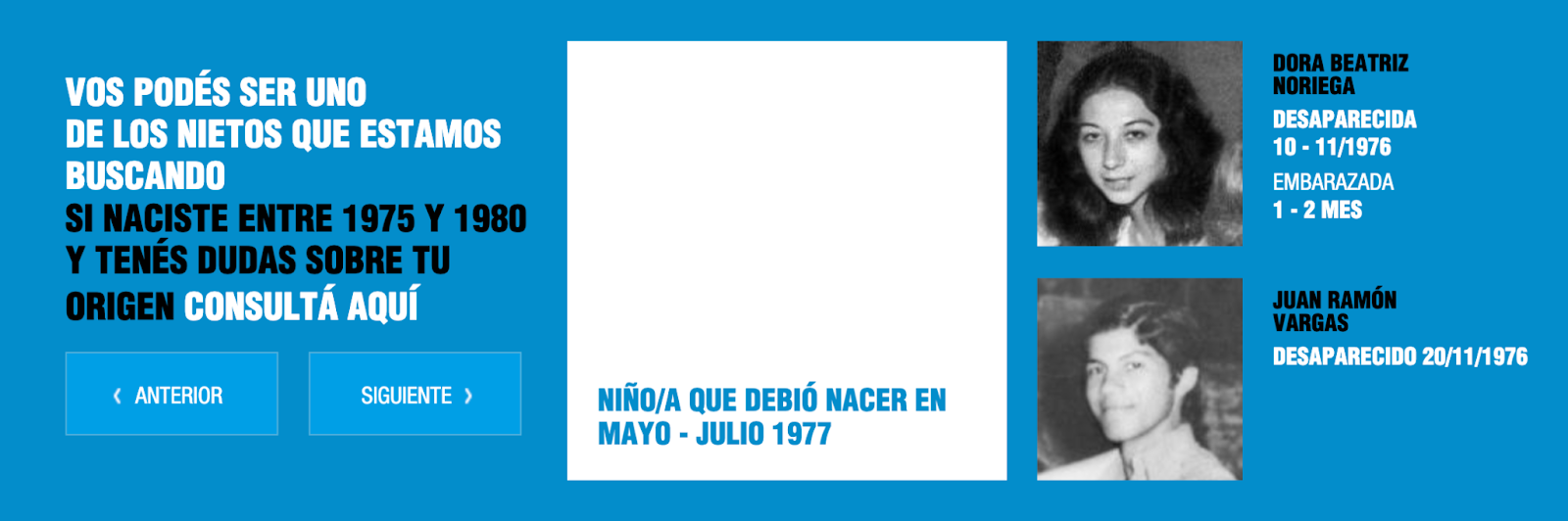

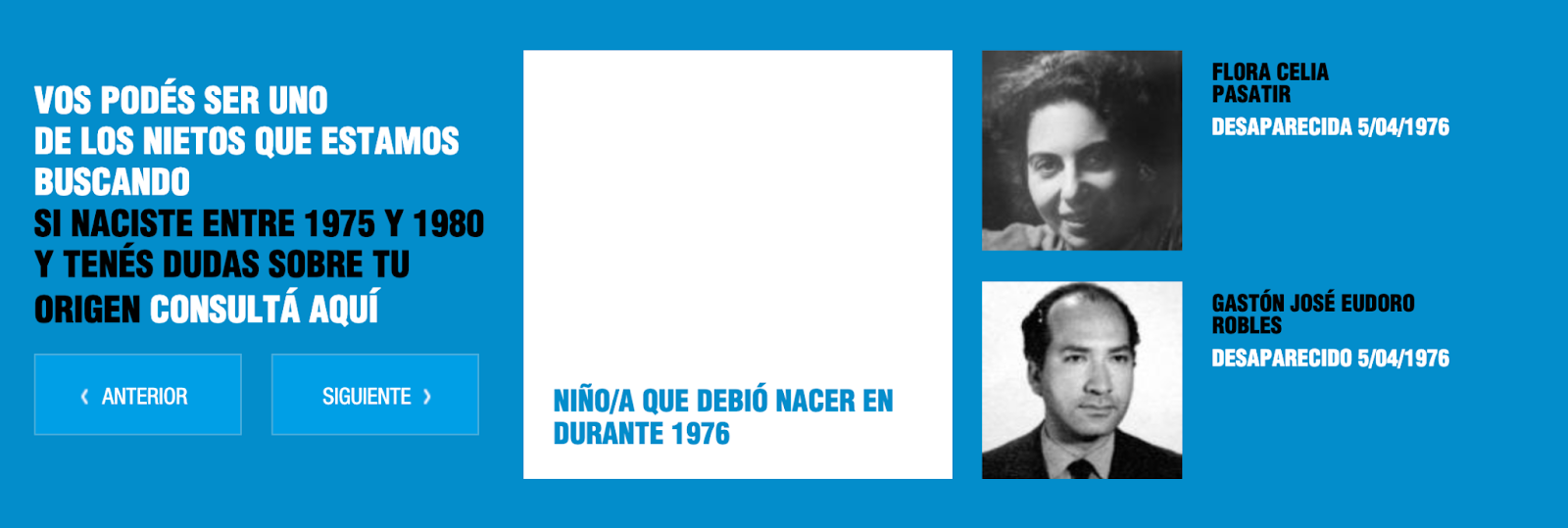

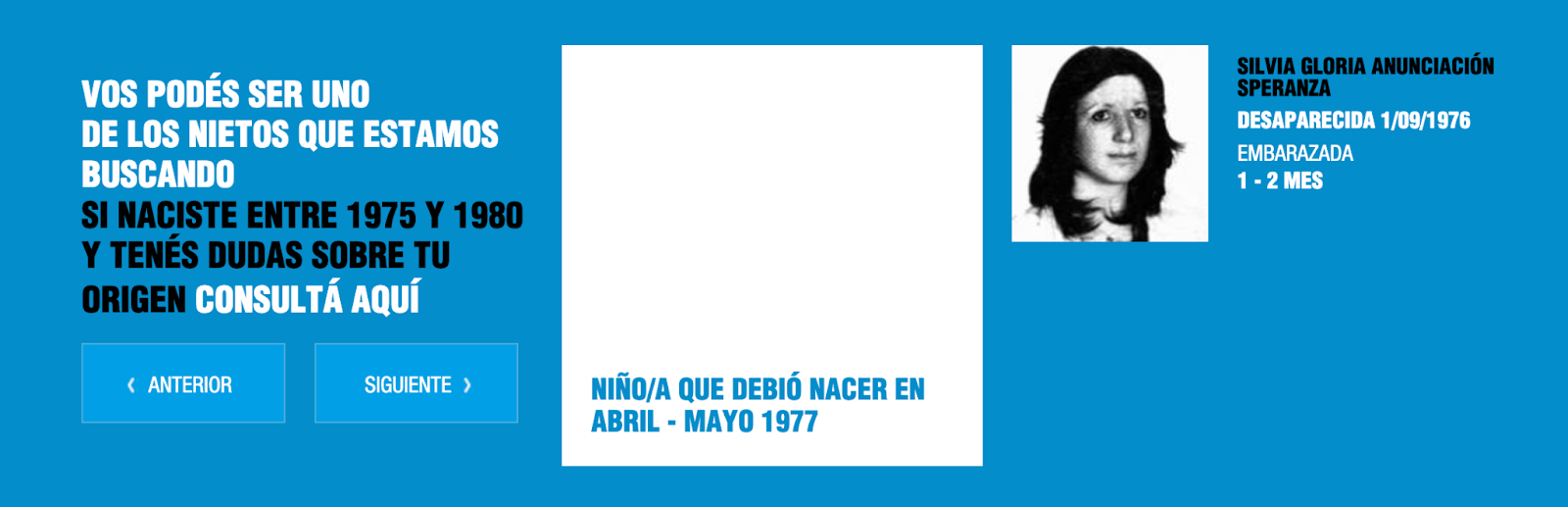

If you go to the grandmothers’ website, a banner on the homepage reads: “You may be one of the grandchildren we are looking for. If you were born between 1975 and 1980 and you have doubts about your origin, find out more here.” A widget next to the text automatically scrolls through photographs of disappeared parents and a blank space where the child’s picture should be:

As of this writing (April 2023), 132 grandchildren out of an estimated five hundred have been found.15

When I was in Argentina in December, the 131st and 132nd grandchild were found.16 It was front page news, as it always is, and the people celebrated, as they always do. The grandmothers, who were once called locas (crazy), are the ones still keeping memory alive. Among the information released about the 131st recovered grandchild was the detail that he had studied philosophy, just like his father, Aldo Hugo Quevedo, disappeared in September–November 1977. “Don’t you understand?” one person wrote in response to the announcement. “They [the agents of the dictatorship] didn’t win. They’ll never win.”17

—

Camila Valle is a writer, translator, editor, and abortion acompañante. Her translation of LASTESIS’s Set Fear on Fire is out now from Verso Books.

From the SftP Archives: In 1987, Barbara Beckwith wrote “Science for Human Rights”, in which she covered the work of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo and the scientists who worked with them, including Mary-Claire King and Ana María Di Lonardo. “‘The place was falling apart—corridors were propped up with wood,’ recalls King. ‘But here was this terrific modern immunology lab—very democratic, very interactive—doing genetic marker paternity testing.’ Many of the researchers working in Di Lonardo’s lab had lost relatives and friends during the military regime and were eager to help locate the disappeared.”

Since 1987, advances in genetic technology moved identification forward, while barriers remained from the oppressive political landscape that necessitated the original project. Camila Valle provides an updated perspective on this remarkable story of activist-driven science, showing us how the grandmothers have modeled for us a “people’s science” across decades.

Notes

- “History of Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo,” Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo (website), accessed May 13, 2023. https://abuelas.org.ar/idiomas/english/history.htm.

- Barbara Beckwith, “Science for Human Rights: Using Genetic Screening and Forensic Science to Find Argentina’s Disappeared,” Science for the People 19, no. 1 (January/February 1987).

- Mary-Claire King, “My Mother Will Never Forgive Them,” Grand Street Magazine 41 (1992): 39–40; Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, Las abuelas y la genética: El aporte de la ciencia en la búsqueda de los chicos desaparecidos (Buenos Aires: Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, 2008). https://www.abuelas.org.ar/archivos/publicacion/LibroGenetica.pdf.

- Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, Las abuelas y la genética; Beckwith, “Science for Human Rights”; Rita Arditti, Searching for Life: The Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo and the Disappeared Children of Argentina (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 67–68.

- Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, Las abuelas y la genética; King, “My Mother Will Never Forgive Them,” 35; Uki Goñi, “A Grandmother’s 36-Year Hunt for the Child Stolen by the Argentinian Junta,” The Guardian, June 7, 2015.

- Most people born in Latin America have scars from the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccine. “A Database of Global BCG Vaccination Policies and Practices,” BCG World Atlas, 3rd edition, accessed May 13, 2023. http://www.bcgatlas.org/

- Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, Las abuelas y la genética; Kelly Suero, “Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo: Breakthrough DNA Advances in the Fight for Human Rights,” The Latin Americanist 62, no. 4 (December 2018). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/tla.12213.

- Nélida Gómez de Navajas, interview by Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, Las abuelas y la genética, 39.

- Ramos Padilla and Juan Martín, Chicha: La fundadora de Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo (Buenos Aires: Dunken, 2006), 236; Ana María Di Lonardo, Pierre Darlu, Max Baur, Cristian Orrego, and Mary-Claire King, “Human Genetics and Human Rights: Identifying the Families of Kidnapped Children,” American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology 5 (1984): 339–47; Arditti, Searching for Life, 70–71.

- A. Ramirez and C. Córica, “Evel de Petrini, Madre del compromiso,” Publicable, April 20, 2017. https://diariopublicable.com/2017/04/20/evel-de-petrini-perfil-madre-plaza-mayo-6711/; “Todos son mis hijos,” Asociación Madres de Plaza de Mayo, May 15, 2023. https://madres.org/todossonmishijos/.

- King, “My Mother Will Never Forgive Them,” 46.

- King, “My Mother Will Never Forgive Them,” 41, 49.

- King, “My Mother Will Never Forgive Them,” 51; Marc Kilstein, “How an American Scientist Helps Grandmothers in Argentina Find Their ‘Stolen’ Grandchildren,” The World, August 7, 2014. https://theworld.org/stories/2014-08-07/how-american-scientist-helps-grandmothers-argentina-find-their-stolen.

- Arditti, Searching for Life, 67.

- Casos resueltos,” Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, accessed May 13, 2023. https://abuelas.org.ar/caso/buscar?tipo=3.

- “Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo Found 132nd Grandchild Stolen by Dictatorship,” Buenos Aires Times, December 12, 2022. https://www.batimes.com.ar/news/argentina/grandmothers-of-plaza-de-mayo-found-132nd-grandchild-stolen-by-dictatorship.phtml.

- Revista y Editorial Sudestada, Facebook post, December 27, 2022. https://www.facebook.com/sudestadarevista/photos/a.198226366881250/5804741649562999.