Building Transtopian Solidarity

By Siufung Law

Volume 26, no. 1, Gender: Beyond Binaries

In light of the recent Florida House ban on gender-affirming healthcare for transgender minors, it is unfortunately unsurprising that Republican lawmakers use religious, scientific, and medical arguments based on a strict, binary understanding of sex.1 This reflects the increasing hostility towards transgender rights in the country. Conservative state lawmakers are actively introducing anti-trans bills that specifically target transgender individuals by restricting their access to gender-affirming care, drag performance, and participation in sports. In response to the concerning trend of discriminatory state legislation on transgender rights, with the American Civil Liberties Union tracking the introduction of more than four hundred anti-trans bills in the first four months of 2023, transgender activists and liberal politicians are steadfast in their insistence on protecting transgender people’s rights to life and their freedom of expressing their gender identity.

In a contrasting development on the other side of the world, Taiwan made history by organizing the first gender-fluid bodybuilding contest in Asia. This groundbreaking event, hosted by Taiwan’s grassroots LGBT+ Sport Association in April 2023, was seen as an educational and political response to the movement to include transgender athletes in sports. What sets this competition apart was that contestants were allowed to compete based on their chosen competition suits rather than their biological sex or gender identity. According to the official social media of the association, the competition featured three categories based on the competition attire: “bikini” (traditionally considered a female category), “sports bra and beach pants” (a newly introduced category), and “beach pants” (traditionally considered a male category).2 This pioneering advocacy for gender fluidity, which challenges a binary notion of sex and beauty, attracted not only transmen and lesbians, but also female-identified individuals who have undergone top surgery (competing in the “beach pants” category) and cis-heterosexual male allies (competing in the “bikini” category) to join the competition. The competition thus challenges the notion that sports competitions have to be organized around a binary notion of biological sex, while also avoiding the idea that people should compete according to gender identity, which has been a central pillar in the movement for transgender participation in sports in the United States. The success in reframing sports competitions beyond both binary sex and gender identity underscores the possibility of understanding transness as less of a fixed category and more of an individual graduation that is integral to human life.

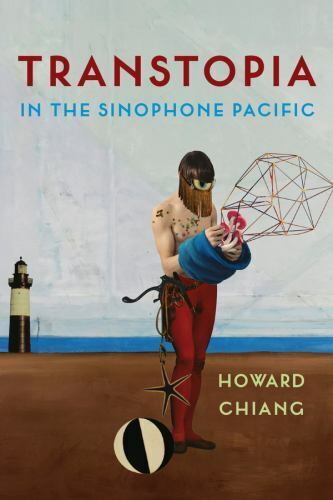

The coexistence of contrasting responses to transgender rights in different parts of the world may be confusing, but as Howard Chiang’s new book, Transtopia in the Sinophone Pacific demonstrates, that very complexity helps us grapple with the multifaceted nature of sexual politics and opens new avenues for solidarity. As Howard Chiang notes, “the politics of transness is most acute in cross-cultural contexts.”3 By focusing on peripheral Sinophone (that is, Chinese-language) LGBTQ communities (including in Taiwan and Hong Kong), Chiang is able to challenge geopolitical hegemonies and consider transgender geopolitics from an entirely new perspective. This is because LGBTQ people living in such places simultaneously face hegemony in both Western and Mainland Chinese forms. Chiang thus proposes a new paradigm for understanding transness that foregrounds LGBTQ experiences within what scholars are increasingly calling, following Shi-mei Shih, a “Sinophone framework,” that is the study of cultures that speak one or more of the languages of China but that exist on the margins of China and its hegemonic notions of “Chineseness” (p. 10, 67). As Chiang demonstrates, identity in Taiwan and Hong Kong already transcends the hegemonic categories imposed by nation-states; LGBTQ movements in such spaces are thus in an especially good position to advance novel and liberatory conceptions of gender. Chiang thus seeks to denaturalize both Western-centrism and China-centrism in queer history and theory; in their place, he offers a non-hierarchical, continuum model of transgender subjectivity that fosters pluralistic coalitions.

Expanding these critical interventions to social movements, particularly queer and trans politics, raises important questions. How can we consider geopolitics as central not only to the writing of transgender history but also to the practice of transgender activism? In what ways can we address the interconnectedness and relationality of the transgender continuum by focusing on cross-cultural politics? What can we learn from queer and trans social movements and histories in Sinophone communities like Taiwan, which are often deemed culturally insignificant?

Chiang coins the term “transtopia” as a way of avoiding the tendency to reinscribe the boundary between “the West and the rest.” Transtopia refers to “different scales of gender transgression that are not always recognizable through the Western notion of transgender” (p. 4) and serves as an antidote to transphobia. His book historicizes gender variance across time and place, reframing transness through the lens of transtopia in the context of mid-twentieth-century sexual science (Chapter 1), the history of a Chinese renyao (“human prodigy”) category (Chapter 3), the representation of castrated subjects in Sinophone cinema (Chapter 4), and the history of transgender activism in the Sinophone Pacific (Chapter 5). Instead of focusing on who qualifies as transgender, a transtopian approach emphasizes how individuals relate to one another through the notion of transgender as a continuum. Chiang claims that thinking about trans politics in this way creates more potent coalitional solidarity.

How can we consider geopolitics as central not only to the writing of transgender history but also to the practice of transgender activism?

But how can we build solidarity through a transtopian approach? For Chiang, one way is to delve into trans history to unpack the global significance of sexologist Harry Benjamin’s (1885–1986) development of the Sex Orientation Scale (SOS). The SOS establishes a continuum between transvestism and transsexualism, allowing for a relational link that transcends discrete boundaries. In contemporary transgender activism, there is often a contentious relationship with medical authorities, particularly regarding the extent to which medical interventions should intervene in the personhood of transgender individuals, and whether gender dysphoria—“the psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one’s sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity”4—should remain a diagnosis of mental illness. Chiang claims that Benjamin’s SOS is a “transtopian innovation in modern sexology” (p. 24) that leverages the productive tension between transgender activism and medical authorities. Historicizing the development of SOS from a dichotomous model of transvestism-transsexualism to a continuum of different stages of intensity of transgender expressions, Chiang emphasizes Benjamin’s conceptual uncertainty of categorizing transgender expressions, which provided an opportunity for the input of sexual minority subjects worldwide and strengthened his taxonomic elaboration. One notable collaborator was Louise Lawrence (1912–1976), who, despite lacking formal medical training, worked with Benjamin to expand transvestism into a diverse category. The SOS continuum then traveled across cultures in the 1960s and 1970s through sexological publications and magazines, inviting a global response from readers, patients, and correspondents, who adopted the full spectrum of Benjamin’s sexological classification to articulate their endocrinological and surgical needs. The construction of a continuum model of transgender through innovation and collaboration points to a different historical and cross-cultural relationality between transgender individuals and medical experts that is less contentious and antagonistic, and more based on solidarity.

How can we build solidarity through a transtopian approach?

In today’s trans politics, a transgender continuum fosters alliances between transgender and cisgender individuals, rather than creating more divisions. Taiwan’s successful launch of the world’s first gender-fluid bodybuilding competition reflects a nonhierarchical continuum that transcends biological sex and gender identity, allowing individuals with a shared view of beauty to form coalitions to increase political visibility. In contrast, anti-trans lawmakers in the United States rely on a discrete, essentialist model of transness to create classifications and surveillance of the heterogeneous population—perpetuating the hierarchies of oppression, cultural citizenship, and authenticity.

For Chiang, understanding the history of the geopolitics of the non-Western parts of the world is essential if we are to reshape our thinking of the global LGBTQ movement through a continuum model. And so he calls for a nuanced approach that considers the structures of political power in different geographical spaces within global LGBTQ activism. A queer Sinophone perspective can disrupt both the assumed Western dominance of LGBTQ activism, and China-centrism in the study of East Asian gender and sexual configurations. In the process, it complicates the way we typically weigh historical queer events, including those seen as pivotal moments in the West.

For example, Chiang shows how Sinophone LGBTQ communities have engaged in creolization—a way of drawing materials from existing systems, reshaping them, and incorporating them into something new that resists colonialism and other forms of hegemony. By comparing the creolization of the Western idea of transgender in contemporary Hong Kong and Taiwan, Chiang traces the asymmetrical trajectories of transgender and queer activism in these regions. In Taiwan, expanding the definition of tongzhi beyond the Western idea of “gay and lesbian” has occurred through two distinct processes. First, it embraced the recognition of transgender rights activism among LGBTQ movements globally. Second, it built on local mobilization following the tragic death of Yeh Yung-chih, a male high-school student who was bullied for expressing femininity and allegedly murdered in the boy’s bathroom in the year 2000. This tragedy sparked radical collaboration between feminists and gay and lesbian activists to incorporate gender diversity into the definition of tongzhi activism, redistributing the queer space traditionally occupied by gay and lesbian subjects to include transgender experiences. In contrast, the success of W, a post-operative MTF transsexual woman, to appeal for her rights to marry her boyfriend in the landmark case of W v. Registrar of Marriages in Hong Kong, risks naturalizing the heterosexual framework of marriage and reducing the complex nature of transgender identities to rigid definitions of transsexuality. Tracing the Hong Kong Supreme Court’s decision to incorporate British Law regarding the inclusion of post-operative transsexuals, Chiang suggests that this case of creolization has perpetuated the very oppression that transgender individuals faced in the first place. Nonetheless, the geopolitics of sexuality in Hong Kong and Taiwan are grounded in the “demand of pluralist recognition and a shared ‘difference/distance’ from mainland China” (p. 206), highlighting the complexities of geopolitical dynamics and contexts in shaping transgender activism in Sinophone regions. Instead of a blanket association of non-Western sexual politics as a product of Western LGBTQ activism, or a simplistic view of Sinophone communities as enacting Chinese queerness, these two asymmetrical examples challenge the dichotomy of the West and the rest by emphasizing the politically contested relationship between Sinophone communities and mainland China.

By charting transgender expressions and politics on a historical continuum, a transtopian approach moves away from a discrete, essentialist notion of transgender and towards a nonhierarchical spectrum of personhoods. As Chiang reminds us, transness emerges from various geographical and temporal locations, indicating that trans history is always complex, multiple, and changing. To “trouble transgender,” as Chiang puts it, is to “dismantle the geographical fetishism” by neither glorifying the West nor nativizing the rest (p. 211). In light of this, a transtopian approach in practicing trans politics rejects privileging any singular experiences as the sole basis for social justice, and fosters alliances and solidarity between transgender and cisgender communities. Transtopia serves as a method to navigate the challenging landscape of today’s transgender politics and work towards social and political justice that is not restricted by gender identity or geographical location.

Transtopia in the Sinophone Pacific

Howard Chiang

Columbia University Press

2021

376 pages

Notes:

- Anthony Izaguirre and Brendan Farrington, “Florida expands ‘Don’t Say Gay’; House OKs anti-LGBTQ bills,” Associated Press, April 19, 2023.

- Beauty Rainbow LGBT+ Sport Association, Instagram.

- Howard Chiang, “Transtopia: A Keyword for Our Century,” June 21, 2021.

- American Psychiatric Association, “What is Gender Dysphoria?”, accessed April 21, 2023.