Review

Secrecy, Science, and the National Security State

By Cliff Conner

Volume 25, no. 3, Killing in the Name Of

The phrase “national security state” has become increasingly familiar as a way to characterize the political reality of the United States today. It implies that the need to keep dangerous knowledge secret has become an essential function of the governing power. The words themselves may seem a shadowy abstraction, but the institutional, ideological, and legal frameworks they denote heavily impinge upon the lives of every person on the planet. Meanwhile, the effort to keep state secrets from the public has gone hand in hand with a systematic invasion of individual privacy to prevent the citizenry from keeping secrets from the state.

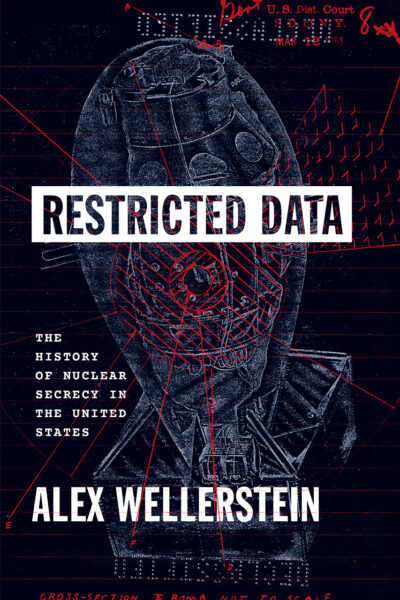

We cannot understand our present political circumstances without knowing the origins and development of the US state secrecy apparatus. It has—for the most part—been a redacted chapter in American history books, a deficiency that historian Alex Wellerstein has boldly and capably set out to remedy in Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States.

We cannot understand our present political circumstances without knowing the origins and development of the US state secrecy apparatus. It has—for the most part—been a redacted chapter in American history books, a deficiency that historian Alex Wellerstein has boldly and capably set out to remedy in Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States.

Wellerstein’s academic specialty is the history of science. That is appropriate because the dangerous knowledge produced by nuclear physicists at the Manhattan Project during the Second World War had to be treated more secretively than any previous knowledge.1

How has the American public allowed the growth of institutionalized secrecy to such monstrous proportions? One step at a time, and the first step was rationalized as necessary to keep Nazi Germany from producing a nuclear weapon. It was “the totalizing, scientific secrecy that the atomic bomb appeared to demand” that makes the early history of the modern national security state essentially a history of nuclear physics secrecy (p. 3).

The phrase “Restricted Data” was the original catchall term for nuclear secrets. They were to be kept so completely under wraps that even their existence was not supposed to be acknowledged, which meant that a euphemism like “Restricted Data” was necessary to camouflage their content.

The relationship between science and society that this history reveals is a reciprocal and mutually reinforcing one. In addition to showing how secretive science has impacted the social order, it also demonstrates how the national security state has shaped the development of science in the United States over the past eighty years. That has not been a healthy development; it has resulted in the subordination of American science to an insatiable drive for military domination of the globe.

How Is It Possible To Write a Secret History of Secrecy?

If there are secrets to be kept, who is allowed to be “in on them”? Alex Wellerstein certainly was not. This may seem like a paradox that would sink his inquiry from the start. Can a historian who is barred from seeing the secrets that are the subject of their investigation have anything to say?

Wellerstein acknowledges “the limitations inherent in trying to write history with an often heavily redacted archival record.” Nevertheless, he has “never sought nor desired an official security clearance.” Having a clearance, he adds, is at best of limited value, and it gives the government the right of censorship over what is published. “If I can’t tell anyone what I know, what’s the point in knowing it?” (p. 9). In fact, with an immense amount of unclassified information available, as the very extensive source notes in his book attest, Wellerstein succeeds in providing an admirably thorough and comprehensive account of the origins of nuclear secrecy.

The Three Periods of Nuclear Secrecy History

To explain how we got from a United States where there was no official secrecy apparatus at all—no legally protected “Confidential,” “Secret,” or “Top Secret” categories of knowledge—to the all-pervasive national security state of today, Wellerstein defines three periods. The first was from the Manhattan Project during the Second World War to the rise of the Cold War; the second extended through the high Cold War to the mid-1960s; and the third was from the Vietnam War to the present.

The first period was characterized by uncertainty, controversy, and experimentation. Although the debates at that time were often subtle and sophisticated, the struggle over secrecy from then on can roughly be regarded as bipolar, with the two opposing points of view described as

the “idealistic” view (“dear to scientists”) that the work of science required the objective study of nature and dissemination of information without restriction, and the “military or nationalistic” view, which held that future wars were inevitable and that it was the duty of the United States to maintain the strongest military position (p. 85).

Spoiler alert: The “military or nationalistic” policies eventually prevailed, and that is the history of the national security state in a nutshell.

Before the Second World War, the notion of state-imposed scientific secrecy would have been an extremely hard sell, both to scientists and to the public. Scientists feared that in addition to hindering the progress of their research, putting governmental blinders on science would produce a scientifically ignorant electorate and a public discourse dominated by speculation, worry, and panic. Traditional norms of scientific openness and cooperation, however, were overwhelmed by intense fears of a Nazi nuclear bomb.

The defeat of the Axis powers in 1945 brought about a policy reversal with regard to the primary foe from whom nuclear secrets were to be kept. Instead of Germany, the enemy would thenceforth be a former ally, the Soviet Union. That generated the contrived anticommunist mass paranoia of the Cold War, and the upshot was the imposition of a vast system of institutionalized secrecy on the practice of science in the United States.

Today, Wellerstein observes, “over seven decades after the end of World War II, and some three decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union,” we find that “nuclear weapons, nuclear secrecy, and nuclear fears show every appearance of being a permanent part of our present world, to the degree that for most it is nearly impossible to imagine it otherwise” (p. 3). But how did this come about? The aforementioned three periods provide the framework of the story.

The central purpose of today’s secrecy apparatus is to conceal the size and scope of the US “forever wars” and the crimes against humanity they entail.

In the first period, the need for nuclear secrecy “was initially propagated by scientists who considered secrecy anathema to their interests.” Early self-censorship efforts “morphed, surprisingly quickly, into a system of government control over scientific publication, and from there into government control over nearly all information relating to atomic research.” It was a classic case of political naïveté and unforeseen consequences. “When the nuclear physicists initiated their call for secrecy, they thought it would be temporary, and controlled by them. They were wrong” (p. 15).

The troglodyte military mentality assumed that security could be attained by simply putting all documented nuclear information under lock and key and threatening draconian punishments for anyone daring to disclose it, but the inadequacy of that approach rapidly became apparent. Most significantly, the essential “secret” of how to make an atomic bomb was a matter of basic principles of theoretical physics that were either already universally known or easily discoverable.

There was one significant piece of unknown information—a real “secret”—before 1945: whether or not the hypothetical explosive release of energy by nuclear fission could actually be made to work in practice. The Trinity atomic test of July 16, 1945 at Los Alamos, New Mexico, gave this secret away to the world, and any lingering doubt was erased three weeks later by the obliteration of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Once that question was settled, the nightmare scenario had materialized: Any nation on Earth could in principle build an atomic bomb capable of destroying any city on Earth in a single blow.

But in principle was not the same as in fact. Possessing the secret of how to make atomic bombs was not enough. To actually construct a physical bomb required raw uranium and the industrial means to purify many tons of it into fissionable material. Accordingly, one line of thought held that the key to nuclear security was not keeping knowledge secret, but gaining and maintaining physical control over worldwide uranium resources. Neither that material strategy nor the hapless efforts to suppress the spread of scientific knowledge served to preserve the US nuclear monopoly for long.

The monopoly lasted only four years, until August 1949, when the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb. Militarists and their Congressional allies blamed spies—most tragically and notoriously, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg—for stealing the secret and giving it to the USSR. Although that was a false narrative, it unfortunately achieved dominance in the national conversation and paved the way for the inexorable growth of the national security state.2

In the second period, the narrative shifted entirely to the Cold Warriors’ side, as the American public succumbed to the Reds-Under-the-Bed obsessions of McCarthyism. The stakes were raised several hundredfold as the debate turned from fission to fusion. With the Soviet Union able to produce nuclear bombs, the issue became whether the United States should pursue the scientific quest for a “superbomb”— meaning the thermonuclear, or hydrogen bomb. Most of the nuclear physicists, with J. Robert Oppenheimer in the lead, vehemently opposed the idea, arguing that a thermonuclear bomb would be useless as a combat weapon and could serve only genocidal purposes.

Again, however, the arguments of the most warmongering science advisors, including Edward Teller and Ernest O. Lawrence, prevailed, and President Truman ordered superbomb research to proceed. Tragically, it was scientifically successful. In November 1952, the United States produced a fusion explosion seven hundred times as powerful as the one that destroyed Hiroshima, and in November 1955 the Soviet Union demonstrated that it, too, could respond in kind. The thermonuclear arms race was on.

The third period of this history began in the 1960s, most notably due to the broad public awakening to the abuses and misuses of classified knowledge during the US war in Southeast Asia. This was an era of public pushback against the secrecy establishment. It produced some partial victories, including the publication of The Pentagon Papers and the passage of the Freedom of Information Act.

These concessions, however, failed to satisfy the critics of state secrecy and led to “a new form of anti-secrecy practice,” in which the critics deliberately published highly classified information as “a form of political action,” and invoked First Amendment guarantees on the freedom of the press “as a potent weapon against the institutions of legal secrecy” (pp. 336–337).

The courageous anti-secrecy activists won some partial victories, but in the long run the national security state became more all-pervasive and unaccountable than ever. As Wellerstein laments, “there are deep questions about the legitimacy of government claims to control information in the name of national security. . . . and yet, the secrecy has persisted” (p. 399).

Beyond Wellerstein

Although Wellerstein’s history of the birth of the national security state is thorough, comprehensive, and conscientious, it regrettably comes up short in its account of how we arrived at our present dilemma. After observing that the Obama administration, “to the dismay of many of its supporters,” had been “one of the most litigious when it came to prosecuting leakers and whistleblowers,” Wellerstein writes, “I am hesitant to try to extend this narrative beyond this point” (p. 394).

Moving beyond that point would have taken him beyond the pale of what is currently acceptable in mainstream public discourse. The present review has already entered this alien territory by condemning the United States’ insatiable drive for military domination of the globe. To push the inquiry further would require in-depth analysis of aspects of official secrecy that Wellerstein mentions only in passing, namely Edward Snowden’s revelations concerning the National Security Agency (NSA), and above all, WikiLeaks and the case of Julian Assange.

Words versus Deeds

The biggest step beyond Wellerstein in the history of official secrets requires recognizing the profound difference between “secrecy of the word” and “secrecy of the deed.” By focusing on classified documents, Wellerstein privileges the written word and neglects much of the monstrous reality of the omniscient national security state that has burgeoned behind the curtain of governmental secrecy.

The public pushback against official secrecy Wellerstein describes has been a one-sided battle of words against deeds. Every time revelations of vast breaches of the public trust have occurred—from the FBI’s COINTELPRO program to Snowden’s exposé of the NSA—the guilty agencies have delivered a public mea culpa and immediately returned to their nefarious covert business-as-usual.

Meanwhile, the national security state’s “secrecy of the deed” has continued with virtual impunity. The US air war on Laos from 1964 through 1973—in which two and a half million tons of explosives were dropped on a small, impoverished country—was called “the secret war” and “the largest covert action in American history,” because it was not conducted by the US Air Force, but by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).3 That was a giant first step in militarizing intelligence, which now routinely carries out secret paramilitary operations and drone strikes in many parts of the globe.

The United States has bombed civilian targets; carried out raids in which children were handcuffed and shot in the head, then summoned an air strike to conceal the deed; gunned down civilians and journalists; deployed “black” units of special forces to carry out extrajudicial captures and killings.

More generally, the central purpose of today’s secrecy apparatus is to conceal the size and scope of the US “forever wars” and the crimes against humanity they entail. According to the New York Times in October 2017, more than 240,000 US troops were stationed in at least 172 countries and territories throughout the world. Much of their activity, including combat, was officially secret. American forces were “actively engaged” not only in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, and Syria, but also in Niger, Somalia, Jordan, Thailand, and elsewhere. “An additional 37,813 troops serve on presumably secret assignment in places listed simply as ‘unknown.’ The Pentagon provided no further explanation.”4

If the institutions of governmental secrecy were on the defensive at the start of the twenty-first century, the 9/11 attacks gave them all the ammunition they needed to beat back their critics and make the national security state increasingly secretive and less accountable. A system of covert surveillance courts known as FISA (Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act) courts had been in existence and operating on the basis of a secret body of law since 1978. After 9/11, however, the powers and reach of the FISA courts grew exponentially. An investigative journalist described them as having “quietly become almost a parallel Supreme Court.”5

Although the NSA, CIA, and the rest of the intelligence community find ways to continue their abysmal deeds despite repeated exposure of the words they try to hide, that does not mean the revelations—whether by leak, by whistleblower, or by declassification—are of no consequence. They have a cumulative political impact that establishment policymakers strongly desire to suppress. The continuing struggle matters.

WikiLeaks and Julian Assange

Wellerstein writes about “a new breed of activist . . . who saw government secrecy as an evil to be challenged and uprooted,” but barely mentions the most potent and effective manifestation of that phenomenon: WikiLeaks. WikiLeaks was founded in 2006 and in 2010 published more than 75 thousand secret military and diplomatic communications about the US war in Afghanistan, and almost four hundred thousand more about the US war in Iraq.

WikiLeaks’s disclosures of myriad crimes against humanity in those wars were dramatic and devastating. The leaked diplomatic cables contained two billion words that in print form would have run to an estimated 30 thousand volumes.6 From them we learned “that the United States has bombed civilian targets; carried out raids in which children were handcuffed and shot in the head, then summoned an air strike to conceal the deed; gunned down civilians and journalists; deployed ‘black’ units of special forces to carry out extrajudicial captures and killings,” and, depressingly, much more.7

The Pentagon, the CIA, the NSA, and the US State Department were shocked and appalled by WikiLeaks’s effectiveness in exposing their war crimes for the world to see. Small wonder that they ardently want to crucify WikiLeaks’s founder, Julian Assange, as a fearsome example to intimidate anyone who might want to emulate him. The Obama administration did not file criminal charges against Assange for fear of setting a dangerous precedent, but the Trump Administration charged him under the Espionage Act with offenses carrying a sentence of 175 years in prison.

When Biden took office in January 2021, many defenders of the First Amendment assumed he would follow Obama’s example and dismiss the charges against Assange, but he did not. In October 2021, a coalition of twenty-five press freedom, civil liberties, and human rights groups sent a letter to Attorney General Merrick Garland urging the Department of Justice to cease its efforts to prosecute Assange. The criminal case against him, they declared, “poses a grave threat to press freedom both in the United States and abroad.”8

The crucial principle at stake is that criminalizing the publishing of government secrets is incompatible with the existence of a free press. What Assange is accused of is legally indistinguishable from actions the New York Times, the Washington Post, and innumerable other establishment news publishers have routinely performed.9 The point is not to enshrine the freedom of the press as an established feature of an exceptionally free America, but to recognize it as an essential social ideal that must be continually fought for.

All defenders of human rights and freedom of the press should demand that the charges against Assange be immediately dropped, and that he be released from prison without further delay. If Assange can be prosecuted and imprisoned for publishing truthful information—“secret” or not— the last glowing embers of a free press will be extinguished and the national security state will reign unchallenged.

Freeing Assange, however, is only the most pressing battle in the Sisyphean struggle to defend the people’s sovereignty against the numbing oppression of the national security state. And as important as exposing US war crimes is, we should aim higher: to prevent them by rebuilding a powerful antiwar movement like the one that forced an end to the criminal assault on Vietnam.

Wellerstein’s history of the origins of the US secrecy establishment is a valuable contribution to the ideological battle against it, but final victory requires—to paraphrase Wellerstein himself, as quoted above—“extending the narrative beyond that point,” to include the struggle for a new form of society geared toward fulfilling human needs.

Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States

Alex Wellerstein

University of Chicago Press

2021

528 pages

—

Cliff Conner is a historian of science. He is the author of The Tragedy of American Science (Haymarket Books, 2020) and A People’s History of Science (Bold Type Books, 2005).

Notes

- There were earlier efforts to protect military secrets (see the Defense Secrets Act of 1911 and the Espionage Act of 1917), but as Wellerstein explains, they “had never been applied to anything as large-scale as the American atomic bomb effort would become“ (p. 33).

- There were Soviet spies in the Manhattan Project and afterwards, but their espionage did not demonstrably advance the timetable of the Soviet nuclear weapons program.

- Joshua Kurlantzick, A Great Place to Have a War: America in Laos and the Birth of a Military CIA (Simon & Schuster, 2017).

- New York Times Editorial Board, “America’s Forever Wars,” New York Times, October 22, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/22/opinion/americas-forever-wars.html.

- Eric Lichtblau, “In Secret, Court Vastly Broadens Powers of N.S.A.,” New York Times, July 6, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/07/us/in-secret-court-vastly-broadens-powers-of-nsa.html.

- Any or all of those two billion words are available on WikiLeaks’ searchable website. Here is the link to WikiLeaks’ PlusD, which is an acronym for “Public Library of US Diplomacy”: https://wikileaks.org/plusd.

- Julian Assange et al., The WikiLeaks Files: The World According to US Empire (London & New York: Verso, 2015), 74–75.

- “ACLU letter to US Department of Justice,” American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), October 15, 2021. https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/assange_letter_on_letterhead.pdf; Also see the joint open letter from The New York Times, The Guardian, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, and El País (November 8, 2022) calling on the US government to drop its charges against Assange: https://www.nytco.com/press/an-open-letter-from-editors-and-publishers-publishing-is-not-a-crime/.

- As legal scholar Marjorie Cohn explains, “No media outlet or journalist has ever been prosecuted under the Espionage Act for publishing truthful information, which is protected First Amendment activity.” That right, she adds, is “an essential tool of journalism.” See Marjorie Cohn, “Assange Faces Extradition for Exposing US War Crimes,” Truthout, October 11, 2020, https://truthout.org/articles/assange-faces-extradition-for-exposing-us-war-crimes/.