Olives, Climate Change, and Zionism

By Mandy Shunnarah

Volume 25, no. 3, Killing in the Name Of

The olive branch is more than a symbol of peace. Since ancient times, Palestinians have tended olive trees—pickling some olives and pressing the vast majority into oil.

Sit at any Palestinian table and olives will be a mainstay of the meal. Whether at breakfast, lunch, or dinner, olives and its derivative “green gold,” olive oil, are ever-present. Able to grow in the harsh desert climates, putting down roots that anchor the trees for generations, olive trees have become a symbol of Palestinian resilience and perseverance against all odds. As such, the trees’ likeness can be seen in Palestinian paintings, embroidery, and other art forms, and the oil is sometimes even used in ritual practices.1 Traditional small-batch olive oil is made by hand, rolling a rock over the olives until the oil is extracted. Larger quantities of olive oil can be made by using more advanced tools like millstones, grinders, presses, vats, and tubing. However the olives are used, olive picking is crucial to the Palestinian economy and way of life, including providing a livelihood for more than 15 percent of Palestinian working women.2 The olive sector is worth between $160 million and $191 million in a good year;3 put into perspective, Palestine’s total agricultural output in 2018 was worth 2.4 billion US dollars.4 Thus, olive oil is central to Palestinian food sovereignty.

In 1948, more than 750,000 Palestinians were exiled from their land.5 Those who remained live under a genocidal regime of military rule—the Nakba is ongoing. That original dispossession continues in every threat against Palestinian lives and livelihood, including those against olive farmers. Not only are olive farmers harassed and beaten en route to their groves, but they also sometimes arrive to find their equipment destroyed or stolen and their trees bulldozed. The reality of the climate crisis is also threatening their livelihood: they face higher temperatures, drought, and pests.6 With the importance of protecting old-growth forests and olive groves—which are extraordinarily good at removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere—the Zionist destruction of Indigenous land and people amounts to environmental terrorism.

—

Palestinians have historically cultivated the land, not just with olive trees, but also with figs, apricots, oranges, and dates. Yet, Zionist propaganda, though a concentrated effort to steal Palestinian land, has insisted on “making the desert bloom.”

The desert has already been blooming and supporting its Indigenous population, as it has for thousands of years. Since the early twentieth century, Zionists have nevertheless co-opted the language of environmentalism and sustainability as a means of forcing the native Arab population off of the lands they covet.7 The Jewish National Fund (JNF), a self-described Zionist organization, has an explicit mission: to acquire land throughout Palestinian territories and plant trees—with “proud Jewish identity.” The JNF claims to have planted 240 million trees over 227,000 acres.8

This tree-planting crusade is detrimental to the land. Pine trees that constitute the colonist’s imaginary of a forest in Europe replace the native plant species and change the soil’s chemistry, such that agricultural crops cannot thrive. This further displaces Palestinians, as well as the nomadic Bedouin peoples, who rely on the land for grazing their cattle. Settlers want to extract from the “blooming desert.” In contrast, the Indigenous approach to land is one of mutual respect and nourishment: the land sustains life and culture, a culture that settler-colonialism wants to erase.

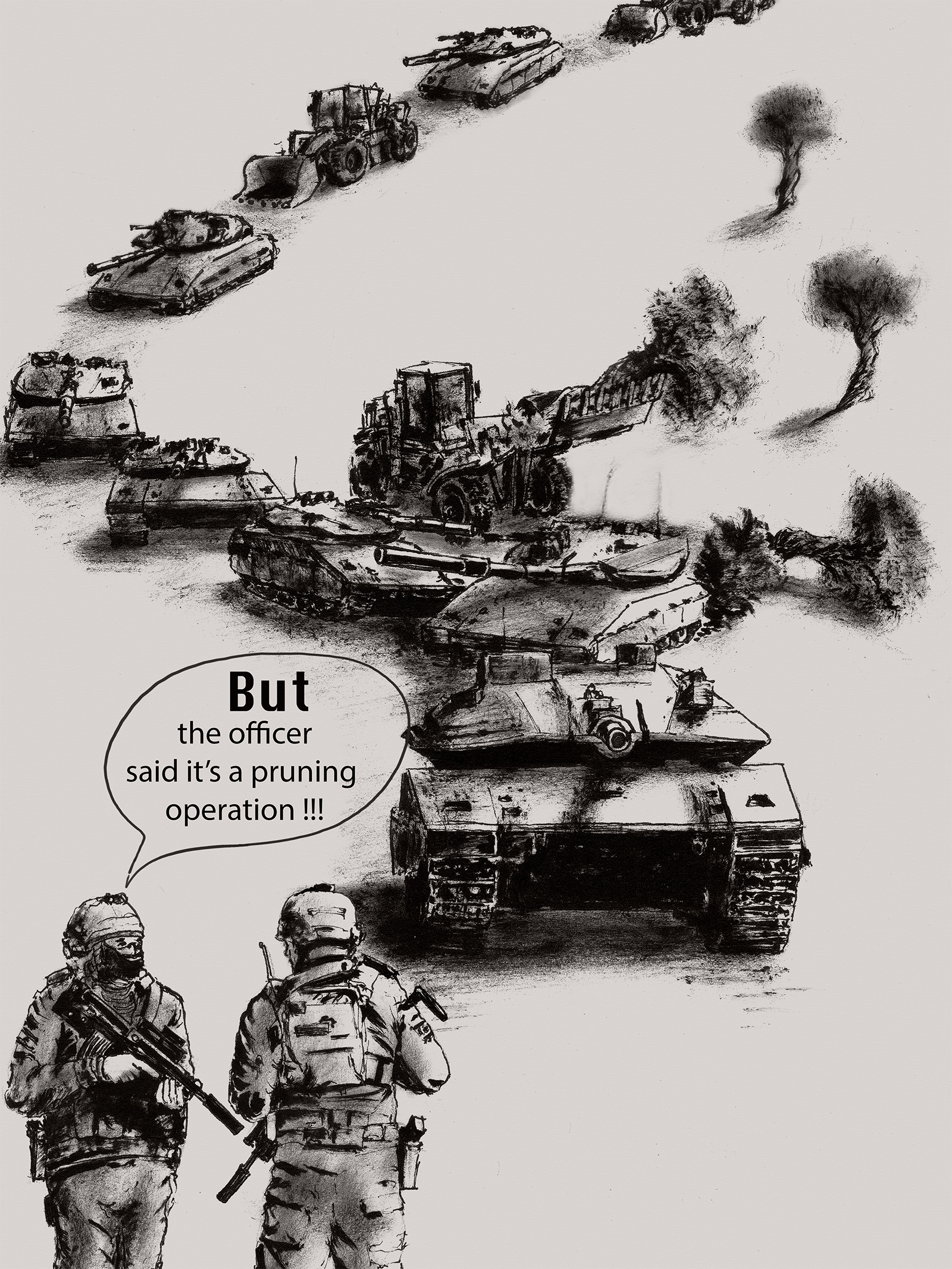

To achieve this end, the Zionist occupation has used a variety of tactics to disrupt the Palestinian economy, including controlling water resources so that groves cannot be irrigated as needed, which is especially important now given the effects of the climate crisis. Additionally, the Zionists instituted a permit system that has prevented olive farmers from accessing their trees for all but a handful of days per year. This has made it difficult, if not impossible, to do necessary maintenance like pruning and weeding, greatly impacting the quality of the harvest. Most egregiously, the Zionists erected walls separating farmers from their groves, slicing up plots of land that have been in the same family for generations.9 Such measures have forced olive farmers to rely on olives of subpar quality. Because of the limited days that farmers are given to access their trees, they might be forced to pick the olives before peak ripeness, affecting the quality of the olive oil produced and therefore the prices that the oil will fetch.

A 1994 New York Times article summarized the struggle succinctly: “The Palestinians planted tiny olive trees; the Israeli soldiers dug them up. The Palestinians lay down in the road to block a bulldozer; the Israelis carted them off to police vans.”10

When Palestinians are exiled, subjugated, and killed, it is not only the people who suffer; the planet suffers as well. Olive groves are considered a carbon sink, which removes atmospheric CO2, pushes it into the soil, and improves the quality of the soil.11 A recent study looking at the olive groves in Europe’s Mediterranean countries concluded that olive trees were effective at sequestering carbon emissions (though not at the rate sufficient to counteract current rates of emission).12

Although olive groves may not be the sole solution to fighting climate change, they are one of the most natural and inexpensive methods, especially when compared to large-scale air and ocean carbon capture technologies.13

The science behind olive groves benefiting the environment is not new—but it has been selectively ignored by the occupation. Israel is a member of the International Olive Council and, in 2016, Israeli representative Daniel Kutner informed the IOC Executive Director, Abdellatif Ghedira, that he would be giving a talk at Conference of Parties 22 (COP22), the United Nations Climate Change Conference, on how olive farming could help alleviate the effects of the climate crisis. This shows that the occupation is fully aware of their environmental impact.14

For all of Israel’s greenwashing (using environmental “friendliness” as a way to detract from human rights abuses), the use of bulldozers and rockets and the emissions from planes, ships, and other military vehicles are far from carbon neutral.15 Atrocities committed against the land and its stewards are not carbon neutral.

In addition to arms, legal and institutional means are used to displace the Indigenous population. Land deeds are one of these means. Take the Salah family, for example: the land on which about three hundred members have lived for generations was disputed by Jewish settlers in courts. In the mind of the colonizers, without proof of ownership, the land must be empty and up for grabs, and so they laid claim.

Indigeneity and historic connection to the land have no need for documentation. To fight back, the Salah family clan and others from the nearby village “linked arms to block an Israeli bulldozer that chugged up the dirt road early this morning belching black, diesel smoke. They dispersed after Israeli troops pushed them out of the way and fired tear gas.”16

That black diesel smoke is an air pollutant that the olive trees could have absorbed and purified, if only they had been allowed to grow. The tear gas, chemicals that poison humans and contain abortifacients, cannot be said to have no effect on the quality of the air, water, or the ground it inevitably seeps into—not to mention the targeted chemical poisonings of the trees themselves.17

“Israeli settlers have uprooted, burned down and chemically poisoned 101,988 olive trees since 2010,” says Nazeh Fkhaida, director of the Palestinian Agricultural Damage Documentation Department. The attacks have caused losses of $47 million to Palestinian farmers.18 The violence and destruction of olive harvests as a vehicle for ethnic cleansing has only increased since that 1994 report in the New York Times. In 2021, the International Committee of the Red Cross reported that 9,300 olive trees were destroyed in the West Bank alone since August 2020.19 These acts of violence were perpetrated on purpose and intensified—sometimes by burning the trees—during harvest season.

Poisoning, uprooting, chopping down, or otherwise damaging an olive tree is not only theft of the lost harvest but also a theft of time. Depending on the specific cultivar of the olive tree, it can take three to five years for the tree to mature enough to produce fruit. Even then, many olive trees are alternate bearers, meaning that they produce a large crop one year and a smaller crop the next year.20 This destruction is more than an injustice to the land. When the Palestinian people are unable to tend their groves due to destruction of harvest, military checkpoints, border walls, and general harrassment from the occupying army and the settlers, they are forced into poverty and into abandoning their olive farms, which the colonizers can then steal.

The olive harvest takes place annually in October and November, and it is a repeated tactic of the Zionist military to attack olive groves and Palestinian farmers every year during this time. Despite this particular form of violence being a yearly occurrence, it often flies under the radar because even more violent tactics are likelier to garner media attention—especially in the West, which woefully underreports Palestinian issues as it is. The underreporting makes justice for the olive farmers even more difficult to come by. A 2015 report from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs made the settlers’ tactics clear: “No action will be taken against the settlers by the Israeli police,” and the police “will say that the attack was in retaliation for Palestinians throwing stones.”21

Stones can hardly put a dent in bulldozers or occupiers in heavily armed military attire. But the Israeli military are often even more concerned about the olive trees themselves, seeing them as a threat to local security. An IDF commander was quoted saying that olive trees are removed “for the safety of settlers,” as the trees protect Palestinian gunmen or stone-throwers, therefore, “No one should tell me that an olive tree is more important than a human life.”22

Ironic, this logic of militarism. It is impossible to ignore the fact that destroying a people’s livelihood, displacing their homes, and denuding the environment is nothing less than ethnic cleansing. On the other hand, as if seeking poetic justice in the absence of real justice, it is only right that olive trees, a universal desire for peace and harmonious living with the land for Palestinians, should be used in active resistance against those who would threaten that peace and harmony.

The occupation tears down olive trees, while Palestinians plant them back!

Science for the People believes in supporting grassroots initiatives in Palestine, working to reroot the Palestinian relationship with the land. Listed below you can find information about the two organizations’ ongoing campaigns. Please get involved!

The Palestinian Social Fund

The Palestinian Social Fund is a grassroots fund that aims to financially support farming cooperatives working primarily in the Occupied West Bank. We believe that there can be no liberation without sovereignty over our daily bread, and we are determined to support young farmers working cooperatively with unconditional, solidarity-based aid.

Last January, we helped the “Land of Despair” cooperative build a greenhouse. Now, we are fundraising to help “The Peasants’ Land” build a greenhouse as well to increase their harvest!

Support: palestiniansocialfund.com/fund

Follow us: @palestiniansocialfund (Instagram)

The Arab Group for the Protection of Nature

The Arab Group for the Protection of Nature is a people’s organization established in 2003 to defend Arab resources and food sovereignty in the face of war and foreign occupation. Our Million Trees Campaign has planted over 2.6 million fruit trees in Palestine supporting 30,000 small-holder farmers, among numerous projects bolstering local food systems.

Join our international digital campaign that will be launched in March 2023; together, we can reach our target of 5 million trees in Palestine.

Donate and plant trees: apnature.org/en/donate-now

Follow us: @apnorg (Instagram and Twitter) @APNature (Facebook)

Notes

- Mel Frykberg, “Environmental Terrorism Cripples Palestinian Farmers,” ReliefWeb, April 6, 2015, https://reliefweb.int/report/occupied-palestinian-territory/environmental-terrorism-cripples-palestinian-farmers; William Booth, “In West Bank, Palestinians Gird for Settler Attacks on Olive Trees,” The Washington Post, October 21, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/in-west-bank-palestinians-gird-for-settler-attacks-on-olive-trees/2014/10/21/eb4f5096-54a8-11e4-892e-602188e70e9c_story.html.

- Mohammed Haddad and Zena Al Tahhan, “Infographic: Palestine’s Olive Industry,” Al Jazeera, October 14, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/10/14/infographic-palestines-olive-industry.

- Haddad and Al Tahhan, “Infographic: Palestine’s Olive Industry.”

- “Main Economic Indicators Related to the Agricultural Sector in Palestine, 2013- 2018 at Current Prices,” Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/statisticsIndicatorsTables.aspx?lang=en&table_id=609.

- “The Nakba Did Not Start or End in 1948,” Al Jazeera, May 23, 2017, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/5/23/the-nakba-did-not-start-or-end-in-1948.

- Passant Rabie, “In Palestine, an Iconic Tree Suffers, Too,” Scienceline, July 19, 2019, https://scienceline.org/2019/07/in-palestine-an-iconic-tree-suffers-too/.

- James Brownsell, “Resistance Is Fertile: Palestine’s Eco-War,” Al Jazeera, November 1, 2011, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2011/11/1/resistance-is-fertile-palestines-eco-war; Eurig Scandrett, “Open Letter to the Environmental Movement,” May 15, 2011, https://eresearch.qmu.ac.uk/handle/20.500.12289/2302.

- Cnaan Liphshiz, “How Planting a Tree in Israel Became Controversial,” The Jerusalem Post, January 14, 2022, https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/article-692517.

- Omeros Demetriou, “Make Olive Oil, Not War,” Olive Oil Times, December 17, 2012, https://www.oliveoiltimes.com/world/make-oil-not-war/31583.

- Chris Hedges, “A Palestinian-Settler Duel: Olive Trees vs. Bulldozers,” The New York Times, December 28, 1994, https://www.nytimes.com/1994/12/28/world/a-palestinian-settler-duel-olive-trees-vs-bulldozers.html.

- Renee Cho, “Can Soil Help Combat Climate Change?,” State of the Planet, February 21, 2018, https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2018/02/21/can-soil-help-combat-climate-change/; Camilla Bateni et al., “Soil Carbon Stock in Olive Groves Agroforestry Systems under Different Management and Soil Characteristics,” Agroforestry Systems 95, no. 5 (June 1, 2021): 951–61.

- Ángel Galán-Martín et al., “The Potential Role of Olive Groves to Deliver Carbon Dioxide Removal in a Carbon-Neutral Europe: Opportunities and Challenges,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 165 (September 1, 2022): 112609.

- Joanna Foster, “Carbon Capture: Reversing Climate Pollution,” Environmental Defense Fund, March 18, 2022, https://www.edf.org/article/carbon-capture-fight-climate-change-stop-climate-pollution; Ally Hirschlag, “To Combat Climate Change, Researchers Want to Pull Carbon Dioxide from the Ocean and Turn It into Rock,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 8, 2021, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/combat-climate-change-researchers-want-to-pull-carbon-dioxide-from-ocean-and-turn-it-into-rock-180977903/.

- Michele Bungaro, “IOC Executive Director Visits the Embassy of Israel,” International Olive Council, October 18, 2016, https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/769-ioc-executive-director-visits-the-embassy-of-israel/.

- “Israeli Greenwashing,” CJPME, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.cjpme.org/fs_210.

- Hedges, “A Palestinian-Settler Duel: Olive Trees vs. Bulldozers.”

- Jennifer L. Brown et al., “Reevaluating Tear Gas Toxicity and Safety,” Inhalation Toxicology 33, no. 6–8 (May 2021): 205–20; Craig Rothenberg et al., “Tear Gas: An Epidemiological and Mechanistic Reassessment,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1378, no. 1 (August 2016): 96–107.

- Salam Abu Sahrar and Ali Abo Rezeg, “Over 100,000 Olive Trees Uprooted by Israel since 2010,” Anadolu Agency, December 19, 2020, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/over-100-000-olive-trees-uprooted-by-israel-since-2010/2082497.

- “9,300 Olive Trees Destroyed by Israel in the West Bank in One Year, Says ICRC,” Middle East Monitor, October 13, 2021, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20211013-9300-olive-trees-destroyed-by-israel-in-the-west-bank-in-one-year-says-icrc/.

- “Best Practices for Growers,” UC Davis Olive Center, accessed September 30, 2022, https://olivecenter.ucdavis.edu/learn/growers.

- Frykberg, “Environmental Terrorism Cripples Palestinian Farmers.”

- Pia Koh, “Destruction of Olive Trees in West Bank Is an Attack on Palestinian Sovereignty, Activists Say,” Olive Oil Times, August 12, 2020, https://www.oliveoiltimes.com/business/africa-middle-east/destruction-of-olive-trees-west-bank-palestinian-sovereignty/84810.