Review

There is No One Trick to Overcoming the Climate Crisis

By Aaron Eisenberg

Volume 25, no. 2, Bleeding Earth

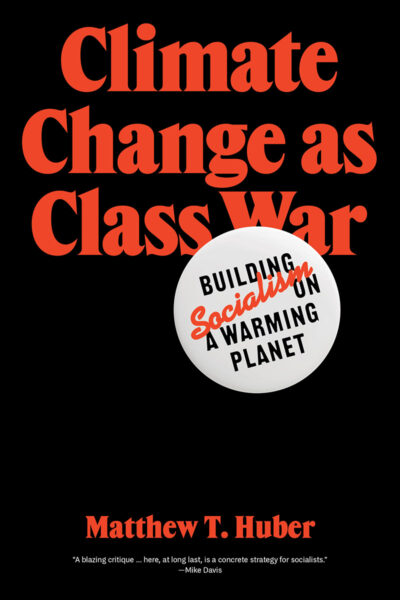

OVER the last decade, increasing climate devastation and a new mobilized base with growing influence have transformed climate from one of many, to a top issue among voters and activists. Yet, meaningful action has not emerged despite this growth in awareness.1 Fossil fuel corporations have tripled down on continuing oil and gas production, and despite flowery press releases, the transition to renewables has been minimal.2 It is within this context that Matt Huber’s new treatise Climate Change as Class War tries to understand the world. Huber, Professor of Geography at Syracuse University, believes that the reason the US climate movement has failed so far is due to the class politics that inherently make it impossible to overcome the climate crisis.

OVER the last decade, increasing climate devastation and a new mobilized base with growing influence have transformed climate from one of many, to a top issue among voters and activists. Yet, meaningful action has not emerged despite this growth in awareness.1 Fossil fuel corporations have tripled down on continuing oil and gas production, and despite flowery press releases, the transition to renewables has been minimal.2 It is within this context that Matt Huber’s new treatise Climate Change as Class War tries to understand the world. Huber, Professor of Geography at Syracuse University, believes that the reason the US climate movement has failed so far is due to the class politics that inherently make it impossible to overcome the climate crisis.

Three Types of Climate Activists, No More, No Less

Huber’s book argues that the failures of the climate movement can be chalked up to an overreliance on the “professional class.” Huber paints a picture of this economically comfortable group in society, with privilege and education that allows them to understand and care about the climate crisis. He contrasts this wealthier and educated class with the working class, who are too busy with daily material struggles to be concerned with climate activism.

Following such a framing, Huber believes that while the working class may seem difficult to engage with, they are, as the majority of society, too important to ignore as a political force. In fact, it is the united working class that holds the key to transforming society and overcoming the worst of the climate crisis. Guiding the book is this perceived dichotomy of an aspirant, activated, working class vis-a-vis a privileged, professional class that currently defines the climate and environmental movements in the United States.3

In Huber’s analysis, the professional class is made up of three strands, all of which share a fundamental belief that society only needs a few tweaks in order to overcome climate chaos. The first is the “Science Communicator,” whose theory of change rests on the idea that if only everyone could understand climate science it would inform political action and compel the public to solve the crisis. Secondly, he describes a “Policy Technocrat,” who seeks to win over right-wingers with market mechanisms that don’t threaten elite political interests. Huber’s third group, “Anti-system Radicals,” believes in “system change,” but one driven by personal guilt over consumption habits rather than any analysis of power. Thus, their solutions do not go beyond small-scale alternatives.

Huber’s typologies and assertions do not actually match the reality of the US left climate space, the apparent target and audience of his book.

By not building a working class mass movement, Huber argues, this professional class’s climate movement has not only failed, but never had a shot at winning. Huber’s critique of liberal climate politics brings to mind seminal works like Overheated: How Capitalism Broke the Planet–And How We Fight Back (2021) by Kate Aronoff and This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate (2014) by Naomi Klein. However, his typologies and assertions do not actually match the reality of the US left climate space, the apparent target and audience of his book.

As a full time climate campaigner, both through my profession and my organizing with Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and the Public Power NY coalition, I can claim some familiarity with the subject of Huber’s critique. The left climate actors certainly have a variety of views on where to focus, but they generally accept the need for a fundamental clean energy transformation. That is, all activists on the left are calling for a form of deep systemic change—a far cry from Huber’s three archetypes.

For a book that then goes on to discuss public power campaigns, it is surprising that Huber categorizes DSA members (at least in New York) and public power campaigners as “Anti-system Radicals” who believe only in small-scale changes. The reality is that DSA campaigns recognize the absolute necessity of the energy system’s complete transformation through a shift to renewables. For Huber, his petty gripes or internecine battles with the Public Power NY campaign inadvertently caused him to do the bidding of the fossil fuel industry.4

Which Working Class Are We Talking About?

This evident disconnect between the Public Power NY campaign and Huber’s limited view of the left climate movement is only one example of how his analysis falls short. The flaws become more glaring when I analyze his definition and understanding of working class engagement in climate struggles.

As alluded to, Huber believes that the working class is most impacted by “abstract domination” of the market and cannot focus on climate campaigns, because climate issues are too abstract for them. This assumption, however, goes against NYC-DSA’s direct organizing experiences against the Astoria Fracked Gas Power Plant. It is, in fact, the fetishization of a certain aspect of the working class that undergirds Huber’s thesis.

The analysis is further compromised by his unwillingness to consider climate movements on the global scale. Working class, Indigenous, and peasant movements in the Global South are overlooked in the book’s understanding of the working class, as the focus was solely on the United States. In fact, Huber critiques Climate Justice Now for having less than 30 percent of its members in “unions,” stating that “the vast majority are peasant and farmer unions” (p. 35). This dismissal of peasants and farmers shines a true light on his agents of change: traditional industrial trade unions in the Global North, above all. To Huber, by not having these industrial unions in the Global North leading, the energy transition has been left to capital, and thus capital has done what capital does: expand.

Selective Ideological Critique

Much of the critique of “Anti-system Radicals” seems to be driven by a strawman hatred of the degrowth movement. Degrowth is a movement that has grown from largely European academic origins, to having wider support in the Global North climate movements.5 The key idea of degrowth is unlearning the dominant ideology of infinite growth as an unchallenged good, but rather seeing sufficiency and living within planetary boundaries sustainably as the desired outcome.6 He collapses all “system change activists” as categorically motivated by degrowth, concerned only with small-scale solutions—again, a failure to grasp the diversity of the degrowth movement.

This same critique of degrowth has been acknowledged by degrowth scholars Jamie Tyberg and Erica Jung, who write, “many in the degrowth movement opt for prefigurative politics of cooperatives, community gardens, and communes, which, while complementary to revolutionary aims, are not contending with class struggle or what comes after. This has opened much of the literature to criticism.”7 Subsequently, many degrowth proponents have indeed considered large-scale transitions and pathways beyond the prefiguration, which Huber focuses exclusively on, as Shmelzer, Vetter, and Vansintjan’s recent book The Future of Degrowth shows. Yet, Huber’s narrow appraisal of degrowth seems to be in service of painting it as a professional class movement that acts as a front for an austerity agenda that is destined to fail.

Because Huber only engages with degrowth at the level of “small is beautiful,” things like reparations, demilitarization, or even prison abolition—all parts of the decarbonizing and degrowth campaigns in the Global North—are ignored.8 Huber later writes that one might include peasants and Indigenous peoples, “even though they do not fit in the Marxist criteria of the proletariat … in the broadly defined working class simply, because they must work to survive” (p. 35). Such a rigid and arguably flawed reading of Marx is far from helpful.

Union Organizing Today and Yesterday, Real and Imagined

Huber’s understanding of the working class rests heavily on his analysis of industrial trade unions in the United States. He presents a comprehensive history of the labor movement and responses to the Great Depression, highlighting how the New Deal came to be as a direct result of the strength of the labor movement. This insight, and the steady decline of labor power in the following decades, leads him to believe that today’s socialists are missing the trick to solving the climate crisis—by failing to center labor from the beginning, specifically unions in the utilities and power sector, climate campaigns are doomed to fail.

Huber focuses on the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) and its 52,000 members in New York State and 725,000 across the United States and Canada. As traditional unions go, IBEW is incredibly powerful. Liz Shuler, who came out of IBEW, was recently reelected President of the AFL-CIO, the largest trade union federation in the United States. IBEW have won impressive gains through their fights over the decades, with union members enjoying comfortable middle and upper-middle class lifestyles. At a time when wages have stagnated nationally, IBEW salaries have steadily increased across the country.9

Make no mistake, these gains should be celebrated for workers. However, we must also ask how these increases continue. Huber spends so much time on the question of how these workers are positioned in production, and the climate movement’s inability to either center these workers from the start or win these unions over through persuasion, that he never questions whether these workers might actually be comfortable with their class position and their leadership’s relatively friendly relationship with industry. If an employer offers substantial increases in wages to utility workers, as they can pass the costs to ratepayers, it is hard to convince a trade union that their employer is the problem.

The “golden years” of American capitalism were fueled by expansionist policies of the US military and Wall Street. This was predicated fully on war and extraction of wealth from the Global South.

This brings up a larger structural point. The post-war compromise of social democracy exchanged labor militancy for consistent wage gains, consequently resulting in dwindling membership.10 IBEW’s membership peaked in the early 1970s with approximately one million members; since then, IBEW has lost a quarter of its members.11 This exchange also came at the expense of the Global South. The “golden years” of American capitalism were fueled by expansionist policies of the US military and Wall Street. This was predicated fully on war and extraction of wealth from the Global South. Less militant labor organizations are also less likely to be internationalist and more likely to be protectionist. This was seen across the labor movement in the United States as the impact of the free trade policies on American labor continues to be felt.12 Overall, it has been the global working class taking the brunt, not the bosses.

Since 2000, utility unions in the US have lost a greater percentage of unionized workers nationally than any other sector.13 Much of this comes down to the political choices and alignments of union leadership.14 Renewable energy creates more jobs than new oil or gas pipelines and upkeep of the existing grid. But it is far more costly; thus fossil fuel corporations fight tooth-and-nail against initiatives for developing renewables. By siding with existing energy corporations who fight against the expansion of renewables in return for contract gains for their members, utility unions allow their ranks to dwindle where consequently, the renewable industry remains a largely un-unionized sector. Short term gains for their members do not always correlate with what is necessary for the long game and ultimately, societal transformation.

Yet, this is exactly the sector which Huber says socialists must focus on by engaging in a rank-and-file strategy within unions like IBEW and the Utility Workers Union of America (UWUA) and creating rapid change within an extremely top down hierarchy. With less than one million members nationally, from a theoretical basis, Huber sees this as a key strategy. This strategy is based on the hope that union leadership will not see this new movement as a threat from within, and that the existing leadership will not seek vengeance against rank-and-file members by opposing all climate legislation as a result. Real life experience with the pushback from the Hotel Trades Council on a reformist strategy in New York City shows the extent to which this is just wishful thinking.15 Furthermore, even when rank-and-file reform slates are successful after decades of toil in unions like Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) or Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD), it still remains difficult to overcome the entrenched dynasties.16

Huber’s strategy is also predicated on an immediate mobilization of an army of socialist and climate activists who are ready, willing, and able to learn and understand the trade, and spend years on waitlists for first apprenticeships, and then journeymen positions. The fact that the current wait for an IBEW apprentice program in New York is three years does not matter. To Huber, this path is the only way to mobilize enough numbers for success. These idealized climate organizers would possess a political adeptness to endure three years of waitlisting to become apprentices before they can wield power through unions. All this is to be accomplished within the ever-tightening timeframe necessary to avoid the worst of the climate crisis.17

This is not to say that organizing in, with, and around unions is not important. The climate movement must have a strategy for engaging with unions, and there are a plethora of attempts via various formations, many of which could be improved and expanded. Potential avenues include working with already existing environmental committees within unions in order to push the idea of climate slates for leadership of locals, and utilizing climate friendly joint council members to pass resolutions internally within the unions in support of legislation. Even more, climate movements could build ties with union leadership that currently exists to break down the barriers between unions and climate activists that are predicated on decades old rifts between environmentalists and labor organizations. From my experience, this is something Public Power NY is attempting to do specifically, as activists from our coalition spent all day with IBEW leadership in May 2022, visiting their training center and working through pathways to achieve a just transition.

The emerging successes of Amazon and Starbucks campaigns, along with the successes of teachers’ unions and nurses’ unions over the last few years, demonstrate a viable path forward. Further, we could even consider activists who are solely dedicated to electoral campaigns for climate candidates. All of these should have been mentioned by Huber, alongside his own strategy, to more robustly clarify the efficacy of his case. The result of such a comparison would instead reveal that in a great struggle requiring multi-pronged approaches, Huber’s strategy could be one of a multiplicity of options.

Organizing within the climate space is occurring at record numbers, and the terrain is shifting on a daily basis. Many of the critiques of the movements and history presented by Huber have no substantial bearing on today’s conversations within current left climate organizing.

Huber further reasons that, because of poor labor standards and lack of unionization in the renewable energy sector, socialists must engage with existing oil and gas utilities. He cites UWUA’s support for Trade Unions for Energy Democracy (TUED) in 2015 as evidence that these unions are waiting in the wings for socialists and climate activists to simply embrace them.18 Yet, UWUA is the only union to ever officially leave TUED, in reaction to their opposition to fracking. Since then, UWUA has fought tooth-and-nail to maintain oil and gas infrastructure across the country, even as their membership has fallen to 50,000 nationally and 8,500 in New York. While UWUA reenters the fold now, advocating for climate policy in New York motivated primarily by protecting job security for its members, this is pushed by fear of market forces rather than mobilizing grassroots support for a clean energy transition.

Unfortunately, Huber does not interrogate whether this is more of a reason to focus on organizing the unorganized solar sector in the United States, to ensure this sector becomes a strong unionized sector. Simply put, just because the gas industry is unionized currently and the solar sector is not, does not mean we should align ourselves uncritically with the union leadership of an ever decreasing gas workforce over the political priorities of an non-unionized solar workforce. California perhaps shows a path forward here: nearly all of California’s solar projects have been unionized with prevailing wage and project labor agreements enshrined.19

There is no doubt that we must transition to renewables to have a livable planet. Huber is right that labor unions have a key role in this transformation; however, his vision for a labor-centered pathway driven by socialists engaged in the rank-and-file strategy within utility unions does not hold merit outside of theory. Huber is also correct to argue in contrary to the popular belief that the transition away from fossil fuels is underway. The reality is that we are seeing emissions increase. I also agree with his points that climate movements are misguided in believing that market forces will drive the transition towards green energy. However, there is no time to gloat, surrender, and point fingers; rather, it is time to commit to a transition powered by a stronger yet nuanced analysis.

Organizing within the climate space is occurring at record numbers, and the terrain is shifting on a daily basis. Many of the critiques of the movements and history presented by Huber have no substantial bearing on today’s conversations within current left climate organizing.20 As Huber goes on to celebrate the Green New Deal framing and correctly urges us all to fight for the Green New Deal movement, it bears repeating that anyone who offers a single path forward is misinterpreting reality and the scale of the challenge. Instead of critiquing a static snapshot of a narrow vision of climate activism based on an anachronistic understanding, we should open the discussion to a variety of tactics and collectively build toward a dynamic, mass movement of the twenty-first century. To do so, it will take long hours of organizing work through trial-and-error, not just academic prescriptions.

Climate Change as Class War: Building Socialism on a Warming Planet

Matthew T. Huber

Verso, 2022

320 pages

Notes

- Nadja Popovic, “Climate Change Rises as a Public Priority. But It’s More Partisan Than Ever,” New York Times, Feb 20, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/02/20/climate/climate-change-polls.html.

- Press releases come directly from industry and are externally covered by press. See Exxon Mobil’s “Why We’re Investing $15 Billion in a Lower Carbon Future,” https://corporate.exxonmobil.com/News/Newsroom/News-releases/2021/1109_Why-we-are-investing-15-billion-in-a-lower-carbon-future, or in major national publications like the New York Times,“Oil Companies Ponder Climate Change, but Profits still Rule,” https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/07/business/energy-environment/oil-companies-climate-change-profits.html.

- This framing is fundamentally false. The poll shows that climate issues are better understood by poorer people. See Brian Kennedy, Alec Tyson, and Cary Funk, “Americans Divided Over Direction of Biden’s Climate Change Policies,” Pew Research Center, July 14, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/07/14/americans-divided-over-direction-of-bidens-climate-change-policies.

- Huber published an op-ed against the Build Public Renewables Act (BPRA), which would ensure that New York State meets its state law renewable mandate by utilizing the New York Power Authority, the largest Public Power provider in the country, because the bill focused on renewables only and did not include his ideal mix of energy grid and likely compelled by his assertion that the campaign is rooted in professional class beliefs, rather than working class beliefs, despite being stewarded by DSA chapters across NY. Huber in the article states he was part of the coalition for years but then left because he realized the errors in its failure to engage with labor from the beginning. Since the coalition has only existed for three years, and Huber was involved in the coalition for the first two years, the critique of labor engagement should follow self-criticism. Furthermore, the BPRA has now been praised by the Business Manager of the NY IBEW Local 1049, who said, “I found the labor language in the latest version of the bill was exceptional … I have never seen anything like it in any legislation that has ever been put forward.” This highlights that perhaps the labor strategy pursued by the coalition is working. See New York State Assembly, Public Hearing on the Role of State Authorities in Renewable Energy Development, July 28, 2022, https://nystateassembly.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=9&clip_id=7059&caption_id=27929611; Matt Huber and Fred Stafford, “The Problem with New York’s Public Power Campaign—and How to Fix It,” The Intercept, July 23, 2022, https://theintercept.com/2022/07/23/new-york-build-public-renewables-act/. For disclosure, I met and engaged with Huber during his involvement in the beginning of the Public Power NY campaign.

- Matthias Shmelzer, Andrea Vetter, and Aaron Vansintjan, The Future is Degrowth (New York: Verso, 2022).

- Jamie Tyberg and Erica Jung, “Demystifying Degrowth,” Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, December 15, 2021, YouTube video, 2:17, https://youtu.be/ELfaaMLmhus.

- Jamie Tyberg and Erica Jung, “Degrowth and Revolutionary Organizing,” Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, October 21, 2021, https://rosalux.nyc/degrowth-and-revolutionary-organizing/.

- Erica Jung, “Rethinking Our Relationship to Land: Degrowth, Abolition, and the United States,” degrowth (blog), September 28, 2020, https://degrowth.info/en/blog/rethinking-our-relationship-to-land-degrowth-abolition-and-the-united-states.

- Pay scales for IBEW workers across the country remain extremely strong. See “IBEW Inside Wireman Pay Scales,” Ultimate Electrician’s Guide, accessed August 3, 2022, https://ultimateelectriciansguide.com/ibew/pay-scales/.

- Kim Moody, An Injury to All: The Decline of American Unionism (New York: Verso, 1988).

- IBEW, History and Structure: Celebrating 125 Years of IBEW Excellence (Washington, D.C.: International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, 2016), http://www.ibew.org/Portals/31/documents/Form%20169%20-%20History%20and%20Structure.pdf.

- See Polina Godz, Them and Us Unionism (Pittsburgh, PA: United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers, July 2020), https://www.ueunion.org/ThemAndUs/.

- National Data across all industries showcase this decline. See “A Look at Union Membership Rates across Industries in 2020,” US Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 25, 2021, https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2021/a-look-at-union-membership-rates-across-industries-in-2020.htm.

- One example in 2020 was four unions signing a Project Labor Agreement with Keystone XL, a major fossil fuel pipeline that President Biden later revoked the permit for. See “Keystone XL Announces Project Labor Agreement with Four US Unions,” GlobeNewswire, August 5, 2020, https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/08/05/2073386/0/en/Keystone-XL-Announces-Project-Labor-Agreement-with-Four-U-S-Unions.html/.

- Pushback on the rank and file strategy from the powerful HTC union in NYC caused major rifts between socialists and organized labor in NYC in 2019, as reported in Politico in 2019. See Sally Goldenberg and Janaki Chadha, “Democratic Socialists Look to Take over New York’s Powerful Labor Unions,” Politico, August 14, 2019, https://www.politico.com/states/new-york/city-hall/story/2019/08/14/democratic-socialists-look-to-take-over-new-yorks-powerful-labor-unions-1141206.

- At the 2022 UAW convention, a resolution put forward by UAWD was defeated which would have done away with previous leadership raises and increased transparency, meaning the wins are not full and complete and must continue being fought for. See Eric D. Lawrence, “UAW Leaders’ Salaries Going up, but Percentage Increase Isn’t as High as in 2018,” Detroit Free Press, August 6, 2022, https://www.freep.com/story/money/cars/2022/08/06/uaw-president-salary-ieb-raises/10245671002/.

- The latest IPCC report estimates thirty months to launch a deep socio-ecological transformation. See “The Evidence is Clear: The Time for Action is Now,” Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, April 4, 2022, https://www.ipcc.ch/2022/04/04/ipcc-ar6-wgiii-pressrelease.

- In my day job, I work with TUED.

- Betony Jones, “Prevailing Wage in Solar can Deliver Good Jobs while Keeping Growth on Track,” UC Berkeley Labor Center, November 12, 2020, https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/prevailing-wage-in-solar-can-deliver-good-jobs-while-keeping-growth-on-track/.

- For example, the book focuses on Citizens’ Climate Lobby (CCL) as a major determinant of climate strategy. In my view, CCL has had absolutely no bearing over the last five years of the climate debates around the Green New Deal discourse, yet Huber focuses on them. More recently, in the Intercept piece Huber admits to no longer being involved in organizing, but rather solely critiquing the Public Power NY campaign.