Sumud and Sovereignty

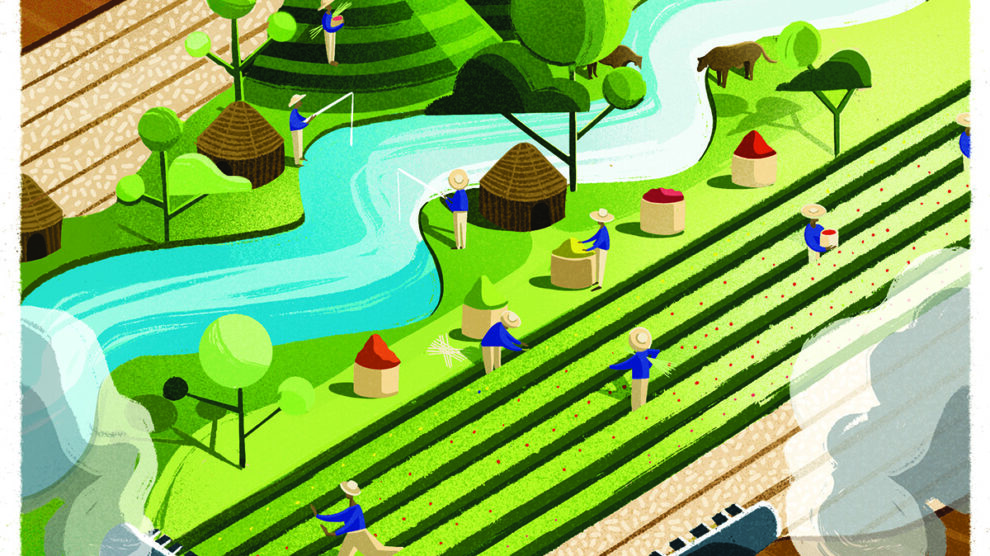

Interview with the Union of Agricultural Work Committees

By Trude Bennett

Volume 25, no. 1, The Soil and the Worker

In a research report of nearly three hundred pages released in February 2022, “Israel’s Apartheid Against Palestinians: Cruel System of Domination and Crime Against Humanity,” Amnesty International (AI) denounces the systematic way in which Israeli “Laws, policies, and institutional practices all work to expel, fragment, and dispossess Palestinians of their land and property….” Though failing to condemn the Israeli occupation or distinguish between Israeli violence and Palestinian resistance, AI has become the most recent human rights group, after Human Rights Watch and B’Tselem, to recognize the apartheid nature of Israeli policy towards Palestinians, a claim articulated by Palestinian Human Rights Groups like Al-Haq, Adalah and Al Mezan, and embedded in the Palestinian civil society call for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions in 2005.

Al specifies that it is describing actions of the Israeli government and condemns any attacks on “Judaism or the Jewish people.” Nonetheless, immediate accusations of antisemitism by Israeli officials and their supporters served to obscure the relationship between two landmark events: the acknowledgment of an apartheid system discriminating against Palestinians by the world’s largest human rights organization, and the October 22, 2021 banning by the Israeli Ministry of Defense of six longstanding and respected groups defending Palestinian human rights. The outlawed Palestinian nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), ranging in their missions from prisoner support to women’s empowerment, are Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association, Al-Haq, Bisan Center for Research and Development, Defense for Children International–Palestine, Union of Agricultural Work Committees, and Union of Palestinian Women’s Committees.

One of the six NGOs, the Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC) is the leading proponent of food sovereignty for Palestinians. A member organization of the global peasants’ movement La Via Campesina (LVC), UAWC has won prestigious international awards for its work against poverty and promotion of sustainable development. Representatives of the Union of Agricultural Work Committees responded to questions from SftP Editorial Collective member Trude Bennett in a written interview.

—

TB: Could you give a brief history of UAWC, explaining your goals and objectives?

UAWC: The Union of Agricultural Work Committees is a civil, independent, and non-profit Palestinian organization. It was established in 1986 following an initiative by a group of agricultural engineers, farmers, and volunteers, both males and females. Our priorities are essentially focused on social and economic empowerment of Palestinian farmers in order to reinforce their steadfastness (sumud) on the land and to achieve food sovereignty. In addition, we work to empower the Palestinian farmers through the innovation of developmental and sustainable agricultural initiatives. Moreover, we contribute to protecting the land and providing legal support to farmers in cases of land confiscation orders. Finally, we endeavor to advance the agricultural sector through developing national policies to support farmers’ rights. As an organization that has been working for over thirty years, we are considered to be one of the biggest and most important agricultural organizations in the West Bank and Gaza. Recognition for our achievements throughout the years include the Equator Prize of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the US Food Sovereignty Alliance Prize, the Arab Thought Foundation Award in Economic Creativity, and most recently, the Energy Globe Award for Sustainability.

TB: Would you say that agroecology is your leading philosophy?

UAWC: Yes, agroecology is a concept that has been a center of attention lately more than ever thanks to the continuous awareness raised amongst the people. We have been implementing this concept as part of its strategic approach since the beginning, linking it to the sustainability goal and the ultimate aim of achieving food sovereignty. The organization prioritizes traditional knowledge; one means is the preservation of indigenous seeds and protecting them through the Local Seed Bank project.

TB: What is your definition of food sovereignty, and how does it relate to political sovereignty?

UAWC: We adopted the definition of LVC for the concept of food sovereignty, taking into account the Palestinian context under Israeli colonialism. Political sovereignty leads to food sovereignty. In the Palestinian context, Israeli colonization controls all natural resources that are the basic blocks in building food sovereignty. The indigenous seeds, the land, and the water are the pillars of Palestinian food sovereignty. About ten thousand years ago, the first agricultural experiments appeared in the Jericho Oasis. The first to reach this deserted oasis and to settle the area near the spring, was a people who knew how to harvest wheat, even if they did not know how to plant it. We know this because they made tools for harvesting wild wheat, which is a fine example of their far-sightedness. They made sickles out of flint, which survived to be found by John Garstang while excavating there in the 1930s. The blade of the old sickle was a piece of deer horn or bone. Modern archaeological and botanical evidence indicates that the cultivation of wheat and barley began in Palestine. This is what was called the “Natufian civilization,” which was named after Wadi al-Natuf northwest of Jerusalem; it lasted about six thousand years, starting around 12,000 BCE.

TB: Do you work in all the occupied territories? How large is your staff, and where are they located?

UAWC: We work in the West Bank and Gaza as main branches, with several sub-branches that cover the entire geographic area. For example, in the West Bank, we have three offices located in Ramallah, Nablus, and Hebron, with close to fifty employees.

TB: Are the current attacks on Bedouins in the Naqab (Negev) related to food sovereignty as well as land tenure, and are they understood that way in the region?

UAWC: In 2015, the occupation government announced the Prawer draft resolution involving massive displacement of Palestinian Bedouins from their ancestral villages, but the decision was halted due to anger and popular pressure. In 2019, the occupation government, through Agriculture Minister Uri Ariel, announced a plan to relocate “about 36,000 Palestinians from the occupied Negev…to ‘inland areas.’” The plan includes the confiscation of 260,000 dunums [26,000 hectares or 64,247 acres] of the occupied Negev land area in the largest confiscation of Palestinian lands since the Nakba in 1948.

So, the current situation is forcible displacement and ethnic cleansing using the tools of the apartheid regime. In the Negev today, the occupation is repeating the Nakba of 48, during which the occupation destroyed more than 500 villages, abandoned their people, and committed massacres and war crimes. The majority of Palestinians in Negev are from Bedouin tribes. Because of their Bedouin lifestyle, they practice their sovereignty over the desert in daily life. The majority of them are herders and pastoralists who know each meter of the desert. They tolerate its heat and its extreme dry climate, and they love it as camels do. They are patient with their difficult life and do not seek any alternative.

TB: How does membership in LVC benefit UAWC or affect your work? What is unique about your situation compared with other peasant organizations in LVC?

UAWC: With membership in LVC, we moved the cause of farmers, fishermen, and rural women from the local and national levels to the Arab and regional levels, and also worked to internationalize the farmers’ cause to defend it in all international forums. As coordinator of LVC in the Arab region, we are an essential pillar for the dissemination of the concepts of food sovereignty and agroecology at the local and Arab regional levels. We have mobilized international solidarity with the Palestinians in general and the peasants in particular. Peasants, fishermen, and rural women suffer from oppression and discrimination, as well as monopolization and control of their resources and production inputs. In addition to all these conditions, the Palestinians are currently languishing under a racist regime that occupies the land, confiscates property, kills farmers, arrests fishermen, and destroys agricultural facilities owned by rural women. The Israeli occupation adds difficulty to the continuity of the dignified life that all human beings desire.

TB: Could you describe your seed bank project and its significance?

UAWC: Our Local Seed Bank was established in 2010 and targeted small-scale farmers, helping them reach seed sovereignty as the first step in achieving food sovereignty. Over the last twelve year, our local seed bank achieved the following:

- Preserved more than 52 local species, belonging to 12 plant families (most of them basic vegetable crops for Palestinian families)

- Reproduced the local seeds in safe amounts for 20 crops

- Contributed to farmers gaining sovereignty over seeds.

- Total number of beneficiaries: 6,635 families

- Total planted area: 1,270 hectares [3,138 acres] of new green cover

- Established Local Seed Bank as an educational center

- Total number of students, women, and farmers receiving training in the Local Seed Bank units: 2,167

- Supported 30 master’s students in their theses related to local seeds

TB: Have you experienced corporate pressures to use genetically modified seeds (GMOs) and chemical pesticides? Is Israel’s failure to ban the use of GMO seeds an additional threat to Palestinian food sovereignty (e.g., through drift of GMO seeds)?

UAWC: As a Local Seed Bank we don’t experience direct pressure, but the GM seeds are one of the biggest challenges for the Local Seed Bank – making the production of pure local seeds a very difficult activity. Unfortunately, the Palestinian farmers are oriented to using GM seeds through different forms of pressure, leading them to abandon their local seeds and resulting in their loss of food sovereignty.

TB: Can you talk about your proposal for a National Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty? Is this part of an international effort?

UAWC: We are a member of The International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty (IPC). IPC is an autonomous and self-organized global platform of small-scale food producers and rural workers’ organizations and grassroots/community-based social movements whose goal is to advance the Food Sovereignty agenda at the global and regional levels. More than 6,000 organizations and 300 million small-scale food producers self-organize through the IPC, sharing the principles and the six pillars of Food Sovereignty as outlined in the Nyeleni 2007 Declaration and synthesis report. The IPC facilitates dialogue and debate among actors from civil society, governments, and other actors in the fields of Food Security and Nutrition, creating a space for discussion independent of political parties, institutions, governments, and the private sector. The legitimacy of the IPC is based on the opportunity it offers to voice the concerns and struggles that a wide variety of civil society organizations and social movements face in their daily practice of advocacy at local, sub-national, regional, and global levels.

TB: Is a strategy of encouraging home gardens compatible with building agricultural collectives?

UAWC: For sure, the production process in Palestine is mainly through small-scale farmers and home gardening in which the whole family contributes collective work. The collective work can be through planning what to plant and when to plant it, and it constitutes a major role in marketing their products.

TB: Do you also envision the development of new methods suited to the land and designed to prevent or adapt to climate change? Will new methods be needed?

UAWC: The potential consequences of changing climate conditions identified in Palestine and proposed options for adaptations are as follows:

| Risks | Adaptations |

| Decreases in optimal farming conditions | Rural livelihood diversification, Irrigation of highest-value crops, Changing cultivation practices, Switching to drought-resistant crops and ruminants |

| Decreased crop and livestock productivity | Change in cropping and grazing patterns for productivity gains, Increased input of agro-chemicals, Increased irrigation of main crops |

| Increased risk of floods | Contingency plan development, Enhanced floodplain management, Increased local-level rainfall interception (e.g., green lands), Reduction of grazing pressures to protect against soil erosion |

| Increased risk of drought and water scarcity | Set clearwater use priorities to increase water use efficiency, Increased regional-level rainfall interception (e.g., afforestation), Increased freshwater production, Awareness-raising on water conservation techniques, Improved field drainage and soil absorption capacity, Use of drought-tolerant crops and ruminants, Local use of treated wastewater for agriculture, Development of new water sources including desalination |

| Increased irrigation requirements | Investment in efficient irrigation equipment, Use of treated wastewater, Increased water harvesting, Desalination of brackish water, Development of new wells |

| Increased risks to public health from reduced drinking water quality | Incorporation of climate risks in national water quality management, Increased water quality monitoring, Identification of minimum household water requirements, Equitable groundwater utilization, Prohibit use of untreated wastewater in agriculture, Increased wastewater treatment, Protection of coastal sand dunes, Coastal protection structures |

TB: Is export of agricultural products a goal? In the long run, do you think Palestinian economic self-sufficiency will depend on other forms of production or income generation in addition to agriculture?

UAWC: The main goal for Palestinian agriculture is to cover the Palestinians’ own need for food; extra products could then be exported for additional income. Palestine’s environment gives Palestinian farmers the opportunity to produce a wide range of crops, which could lead to self-sufficiency of basic foods. Many other income generation sectors like industrial and commerce are present and developing.

TB: What are the health consequences of land loss, food insecurity, high unemployment, and coercion to provide low wage and dangerous labor in Israel or the settlements, as well as the intense stress of living under occupation? What are the main physical and mental health problems you observe in people of different ages?

UAWC: For years, the Palestinian people have been suffering from two types of trauma resulting from the circumstances surrounding continuous policies of aggression:

First type: This trauma has been ongoing since 1948 from the systematic, constant aggression that targets the life of the Palestinian person, represented by killing, physical abuse, torture, psychological abuse, and imprisonment. This aggression targets both the individual and collective self, as well as Palestinian property and opportunities to make a decent livelihood from agricultural and commercial sources, through the policy of demolition, sabotage, confiscation of lands, and uprooting of trees.

Second type: This form of trauma is linked to the shock resulting from the construction of the separation wall, the imposition of complete isolation, and the siege of hundreds of Palestinians inside what is described in the global political literature as a “ghetto” (or state of isolation).

TB: What are the main obstacles and challenges you face in your work?

UAWC: Working in Area C,1 which is the mission of UAWC, has been a challenge since the beginning due to the inhumane situation there and the attacks by settlers and occupation forces. However, the recent Israeli incitement attacks and campaigns have to be the biggest challenge that we have faced and is currently facing. These attacks aim to criminalize our civil society work in an effort to stop donors from funding UAWC and stop its projects in Area C. Although these allegations have been proven several times to be baseless, the international community’s position on standing up for UAWC and the other five organizations being attacked remains very limited and timid.

TB: You place an emphasis on youth participation in your plans for the future. Globally, high rates of rural poverty and lack of opportunity tend to drive rural-to-urban migration. Is it your experience that Palestinian youth desire to stay in their villages if they become engaged in collective agricultural projects?

UAWC: The most important characteristics and indicators related to the youth component in Palestine and their relations with the agricultural sector are the following:

- The data indicate an increase in the average age of agricultural holders through inheritance or purchase, and this usually happens in middle and old age. Agriculture is considered an unprofitable activity, which also reduces the incentive for youth to work in this sector. It was noted, however, that the average age of owners of animal holdings has decreased, perhaps because of the ease and low cost of acquiring animals.

- The youth component in temporary agricultural employment (often for family members, and unpaid) is about 58%, while the contribution of youth in permanent agricultural employment is about one third.

- To clarify matters, the data issued by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics for the Tulkarm area was used as a representative example of agricultural areas. Statistics indicate that about4% of the landlords in Tulkarm are from the younger generation under 30 years old.

- The average monthly income in shekels for self-employed workers (West Bank 2016) in the activities of agriculture, hunting, forestry, and fishing is 1,843 shekels [591 USD], which is the lowest average income among all job categories and accounts for 70% of the average monthly income for those workers.

- For approximately two thirds of agricultural holders, agriculture is not their main occupation. For example, in the Tulkarm region, the proportion in this category is approximately 72%, even though it is primarily an agricultural area. This is due to the low value of agricultural production compared to other activities, in addition to the decreased area of holdings.

- Agricultural employment is heading towards shrinkage and fading, as there has been a sharp decrease in the percentage of total workers in the agricultural sector for both sexes. The percentage for men reached 12.6% in 2006 and decreased to 7.0% in 2016; for women it declined from 38.6% in 2007 to 9.0% in 2016.

- The agricultural sector has a major role in hidden unemployment since agricultural work is less intensive and time-consuming compared to many other activities. About 34% of agricultural laborers work at a weekly rate of 1–14 hours, compared to only 5% of those who work in agriculture more than 35 hours a week.

- Data indicate that agricultural workers are the least fortunate in educational opportunities; only 1.9% of agricultural workers have more than 13 years of education.

In order to encourage young people to work on their lands, UAWC has worked to implement many projects for unemployed youth as well as newly graduated agricultural engineers. These projects have included innovative pilots in areas such as capacity building, training, and providing material and in-kind support and vocational training. These activities contributed to permanent job opportunities for more than 60 percent of the targeted youth group members. In this context, UAWC believes that young people can remain in their villages if they engage in individual or collective agricultural projects.

TB: Has UAWC suffered harassment from the Israeli government in the past?

UAWC: We have been a target of Israeli settler organizations that are well connected to the Israeli government for the last ten years. On-site actions have included disruption of project implementation and harassment of staff. But this is the first time that the harassment has reached a much larger scale by labeling a human rights defender organization as a “terrorist organization.”

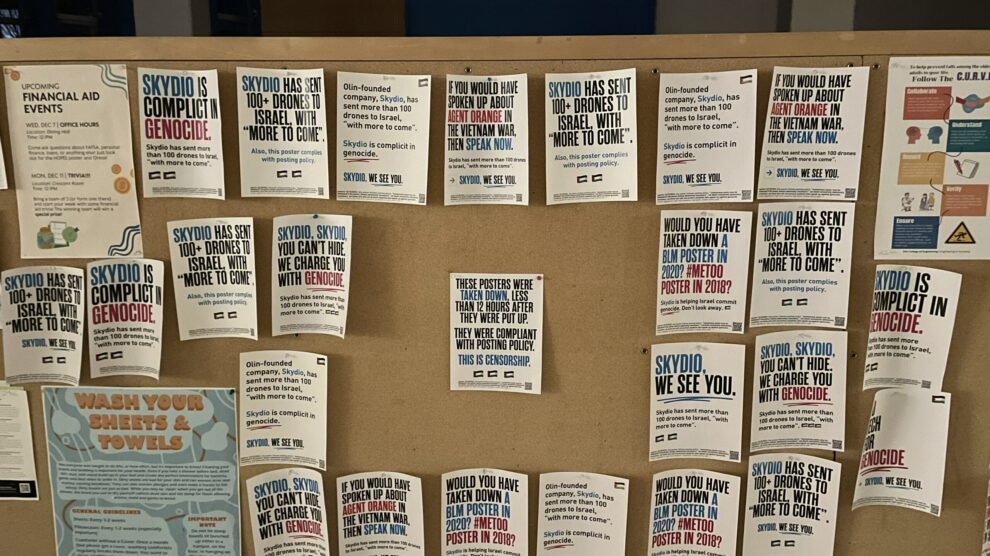

TB: What was the purpose or intent of Israel’s October 2021 designation of UAWC and five other Palestinian human rights organizations as so-called “terrorist organizations”?2

UAWC: The purpose is clear. Israel targeted the six largest and most quoted civil society organizations in Palestine. The one thing these organizations have in common is that they work in the field of human rights to expose the atrocities of Israeli occupation and settler practices on our land. As the organizations have grown larger, they now hold great influence in the international arena as well-respected and professional organizations wholly dedicated to their goals. This is something that the Israeli government fears and cannot let pass. For example, just seeing the great achievements accomplished by UAWC in Area C that worked to protect these lands from confiscation, or Al-Haq’s efforts in the International Criminal Court (ICC) to investigate Israeli crimes—these are adequate reasons to make the Israeli government shut down these organizations. The most convenient way would be the terrorist labeling in hopes of rousing fear and scaring off international donors to stop their support and funds to the organizations, ultimately paralyzing their work.

TB: What has been the impact of the designation on your work, e.g., effect on donors, banking or legal problems?

UAWC: The designation decision has had a negative impact on our work. It frightened a number of UAWC’s donors and consequently they decided to postpone work and payments until consultations were conducted with their legal authorities. The aim behind the designation is to frighten the donors and employees of the organizations and thus undermine the work of the organizations, which frankly has contributed to weakening the organizations’ ability to reach their target communities. The decision also encouraged Israeli right-wing institutions such as NGO Monitor and UK Lawyers for Israel (UKLFI) to increase their pressure on Palestinian civil society organizations and the six organizations in particular.

In the case of UAWC, the decision deprives about twenty thousand Palestinian farmers of direct and other support. The decision also aids in preparing for the annexation of Area C, which is being implemented on the ground at an accelerating pace. By undermining the work of the six organizations, the decision paves the way for the process of expelling Palestinians from Area C and building more settlements. The decision doubled the pressure on the work teams, which are already under great pressure due to the nature of their work in areas threatened with confiscation and close to army camps in Area C.

TB: What are the implications of this attack for human rights groups in other countries?

UAWC: The decision contradicts all principles of democracy and human rights and is clearly racist. It restricts the work of human rights groups and imposes more limitations on them; it aims to silence them and curtail their influence at the international and local levels.

TB: You do not rely on international aid or relief projects for steering your direction. How can allies provide support in this difficult period, politically or financially?

UAWC: There is an urgent need to ensure the work of the classified organizations, especially UAWC, given the dramatic decline in external funding due to the threats of the Israeli government to the donors. The organizations are suffering from a financial crisis as a result of the designation. Therefore there is a need for campaigns to raise funds for us, based on the importance of supporting the right of these organizations to continue their work as defenders of human rights.

TB: For those of us in the United States, do you see value in petitions, letter-writing campaigns, and legislative strategies such as Rep. Betty McCollum’s introduction of House Resolution 751 “condemning the oppressive designation by the Government of Israel of six prominent Palestinian groups as terrorist organizations…”?3

UAWC: We believe that the position of the US Administration is the most important, because Israel is a pampered ally of the United States. Therefore, the US Administration is the only one capable of forcing Israel to retract the decision. The efforts of petitions, official letters, etc. constitute an important role in pushing a demand from the people to officials. If continued in efficient ways, they can ultimately pressure the Administration to blatantly denounce the decision and demand its revocation.

—

In an earlier effort to discredit UAWC, Israel arrested two former UAWC staff members in October 2019, charged them with a terrorist act, and claimed the organization was allied with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. One of UAWC’s main donors, the government of the Netherlands, subsequently announced it was suspending funding and commissioned an independent investigation of UAWC’s activities from 2012 to 2020. As in the case of a similar 2012 Australian report, the Dutch inquiry found no evidence for the accusations when it concluded in November 2021.4 In spite of finding no new support for the recent Israeli claims, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced on January 5, 2022 that it was discontinuing all support for UAWC—much to the dismay of the NGO, its supporters, and proponents of the “rule of law.”

The Israeli attacks on Palestinian human rights groups may seem irrational, but they are part of a multi-faceted plan to seize and undermine traditional Palestinian lands, homes, and livelihoods. The weapons of occupation are multiple and ruthless—military, police, and settler violence; demolition of homes and mosques; seizure of private and communal land for “recreational areas” that exclude Palestinians; bulldozing of arable land, degradation of the soil by aerial spraying of chemical herbicides, and theft of water rights; afforestation of farming and grazing lands leading to displacement and disastrous fires; and extreme violence in suppressing protests against all of these life-denying strategies.

Notes

- The Oslo Accords, signed in 1995, divided the Occupied West Bank into three areas, A, B, C. In Area C, covering 60 percent of the West Bank (about 330,000 hectares) where 300,000 Palestinians and more than 340,000 Israeli settlers live. Israel controls all security and civil-related issues, including land allocation, planning, construction, and infrastructure. The Palestinian Authority is solely involved in the provisioning of education and healthcare. Access to lands for Palestinian development, and farming, is restricted to 30 percent of the territory of Area C, the remaining 70 percent are closed military zones and nature reserves that require special permits for development. See Ahmad El-Atrash, “Israel’s Stranglehold on Area C: Development as Resistance,” Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network, Septebmer 27, 2018, https://al-shabaka.org/commentaries/israels-stranglehold-on-area-c-development-as-resistance/.

- Rami Almeghari, “Saving Seeds, Counting Cows: Work of a ‘Terror’ Group?” January 26, 2022, Electronic Intifada, https://electronicintifada.net/content/saving-seeds-counting-cows-work-terror-group/34711.

- “McCollum Resolution Calls on the U.S House to Condemn Isrrael’s Decision to Designate Six Prominent Palestinian Human Rights and Civil Society Groups as Terrorist Organizations,” U.S. Congresswoman Betty McCollum, October 28, 2021, https://mccollum.house.gov/media/press-releases/mccollum-resolution-calls-us-house-condemn-israel-s-repressive-decision.

- Mustafa Abu Sneineh, “Netherlands ends funding to Palesitnian agricultural NGO outlawed by Israel,” Middle East Eye, January 6, 2022, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/netherlands-ends-funding-israel-outlawed-palestinian-ngo/