Fear of a Black Planet: Archival Notes

By Justin Davis

Volume 25, no. 1, The Soil and the Worker

Volume 25, no. 2, Bleeding Earth

“See if you grew up where we grew up in this environment /

you’d see we’re not the product, we’re the product times ten.”

—Cavalier“You can plan a pretty picnic, but you can’t predict the weather.”

—André 3000

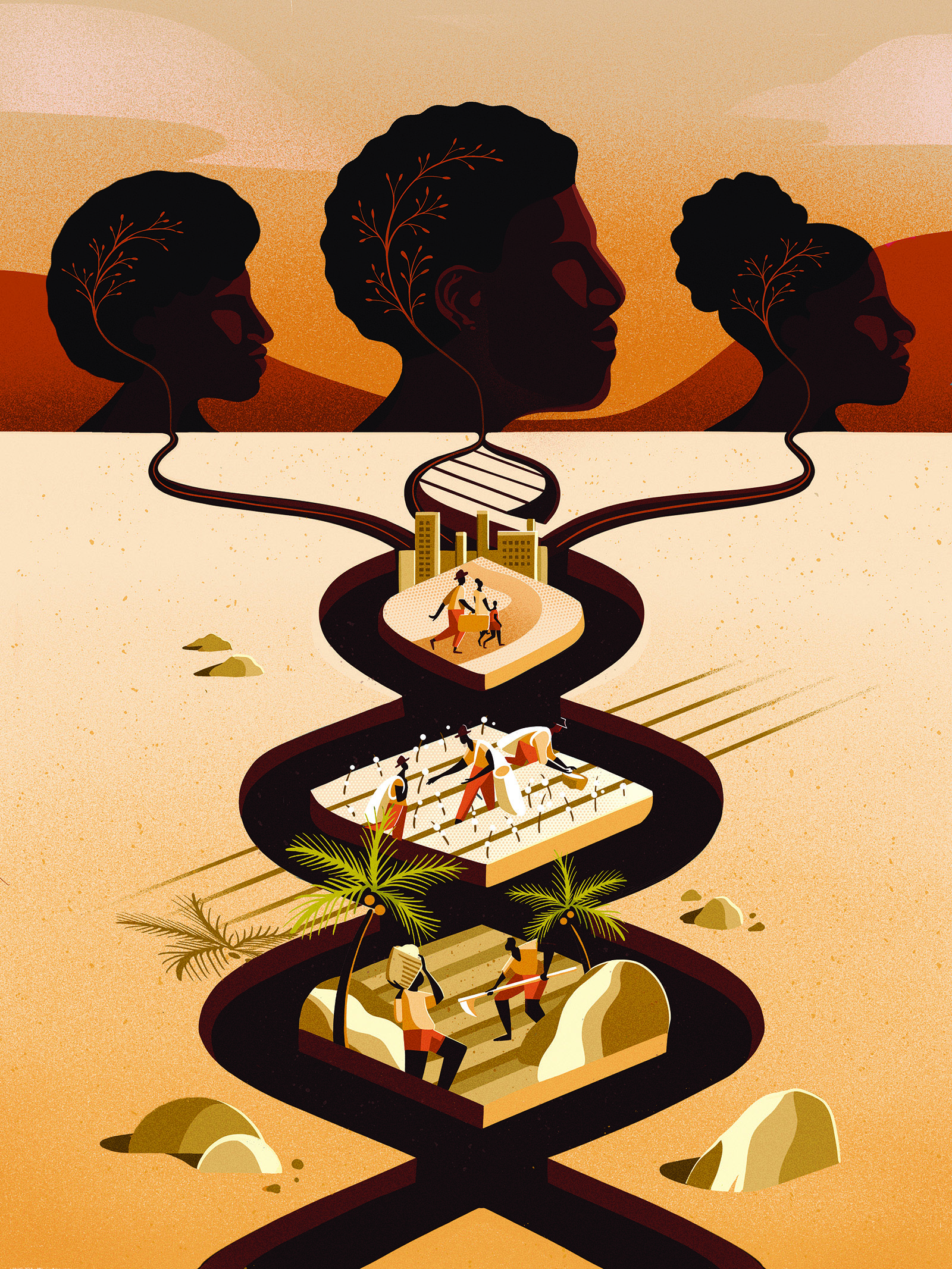

Blackness as the field. Blackness as the harvest. Blackness as toxin, as invasive species.

I recently read a Tweet from writer and archivist Che Gossett that’s been lodged in my brain stem ever since: “living in the afterlife of slavery means living on the planetary afterlife of the plantation.”1 What I hope to do here is dredge up some pieces of that afterlife: places where we can see the innate ecology of Blackness, ways that America’s environmental crisis has always been a crisis of racial hierarchy.

Much of my political life has involved environmental justice—I’ve worked in neighborhoods with toxic water basins, where signs sprout up urging you not to fish; I’ve gone to city council meetings countless times about shoddy public transit service; I’ve watched my friends fight against landfills, push for better parks, and expose soil contaminated by decades of military dumping. I’ve learned intimately how greenspace and infrastructure fall back on a racial logic that people often don’t see. But this isn’t about that. This is about how the land has always held identity inside it. How power is something you live in, something that traps heat inside it, that churns the sky above your head and makes you wonder when lightning might strike.

“All the Crops Except Negroes Are Injured”

Let’s start where Gossett’s Tweet does, or more precisely, before it: in the life of slavery.

The project of chattel slavery demanded its own American landscape, one designed to hold as much latent wealth as possible. The plantation was its basic unit. Throughout the nineteenth century, the biggest plantations ballooned to hold massive crop yields, crowds kidnapped through the legal and illegal slave trade, and generations of selective breeding. The country’s slave population and its farmland grew in tandem: in 1860, slaves were over 40 percent of the population in almost half of the Southern states,2 and “the average, owner-operated farm in the US South and border states comprised well over three hundred acres.”3 So the fate of the plantation and the fate of Black people were always tied together—tied by the fate of the South’s white landowning class. When Mississippi seceded from the United States in 1861, its declaration of secession made clear what the plantation’s survival meant to them.

Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization.4

It’s striking how ecological this reasoning is: a “law of nature” binds the Black body to slavery. Repeatedly, slavery’s defenders argued that only Black people could handle the heat and humidity that plantations required. Africa’s climate sets up Black folks to bear the weight of the Southern economy. But the declaration goes further: it argues that the tropical conditions shared by Africa and the Americas keep civil society functioning and hold up the economy in the broadest sense of the word. If you disconnect Blackness from the plantation, you risk making the whole planet fall apart.

—

In his 2019 book Necropolitics, political theorist Achille Mbembe tells us a little about the process of forming plantations, “about cutting down, burning, and routinely razing forests and trees; about replacing the natural vegetation with cotton and sugar cane.”5 While Native Americans were being pushed off their homes, unwilling or unable to do the free labor that colonizers wanted, countless Africans were brought in to terraform, to “[replace] an ecosystem with an agrosystem.”

But the context in which Mbembe brings this up is important. It’s incomplete to see the plantation as only a place where Black folks had to work, eat, and sleep. The plantation shared a common birthplace with Black identity itself—both were being created at the same time. “Here, life came to be shaped according to an essentially racial principle,” says Mbembe, “race, far from being a simple biological signifier, referred to a worldless and soilless body, a body of combustible energy, a sort of double of nature.”6

At a certain point, the internal conditions of slaves—their health, the physical and mental toll on their lives—couldn’t be separated from their surroundings: the air, the weather, wildlife, microbes, and crops. And this connection between race and the plantation has another side: Black labor in the South has changed its environment long term. It’s interesting how Mbembe argues that plantations made the Black body a “soilless body” when one of the most common side effects of plantation farming was soil erosion. Growing tobacco could exhaust a field in just three or four years, as a lack of nutrients in the soil could turn it acidic, and the constant scratching at the surface could make considerable dips in the landscape.7 Cotton farmers had to rotate their fields with other crops to avoid this, and groups of slaves stepped over and through them frequently to kill bollworms and dig up weeds. Literary scholar Monique Allewaert distills this in her book Ariel’s Ecology when she says that “Plantation spaces possessed those who traversed them.”8

—

The summer after I graduated high school, I tracked down the land my ancestors were forced to work on. My family’s always kept a deep connection to the town in Missouri’s bootheel where my great-great-great-grandparents lived; sometime in the late 1800s, they built our family home there from scratch, cutting stone slabs, planting peach trees and wells in the soil. I had made day trips there before to shop with my mom and grandma and visit my cousins who lived on the same street where the house once stood. But this time, my mom and I went to the county archives and asked about the slave owners my grandma had named for us. We watched volunteers bring out boxes of documents that belonged to them: a will, a tombstone order, receipts for taxes and vaccinations, and repairing a buggy. The one that stuck to me the most, though, was an inventory, dated October 1861, scrawled in a loose cursive: “One tract of land containing fifty acres. One tract of land containing one hundred and sixty one acres. Esther, Addison, Robert, Van Buren, Caroline, Charles, Nancy, Alexander.” My family, other families too, and sprawling fields, all counted together.

So Blackness was a seed to be planted, a shoot to be cut down and regrown. It was a natural resource to be harvested: like tobacco, like sugar, like the cotton that juts out of the east Arkansas plains like teeth as I drive down highway 55.

I’m reminded of a newspaper clipping from the 1850s, cut from a book of one of Frederick Douglass’s speeches. It has no author or date, nothing to give it a concrete origin. It reads simply: “A belated snow-storm has just paid the interior of South Carolina a visit. It is thought that all the crops except negroes are injured.”9 So Blackness was a seed to be planted, a shoot to be cut down and regrown. It was a natural resource to be harvested: like tobacco, like sugar, like the cotton that juts out of the east Arkansas plains like teeth as I drive down highway 55. The American pastoral has always had a certain violence lying under the grass, not far beneath our shoes—it’s hard for me to look at a Romantic landscape, for example, without considering the conquest that let white painters see it. But what I’m saying is that Blackness is also the grass. It’s the field that the grass is growing into, the one your heel presses down on without thinking about it.

—

In 1921, a few days before Christmas, US congressman James Benjamin Aswell, native of Vernon Parish, Lousisiana, was in D.C., fighting tooth and nail against an anti-lynching bill.

Aswell contended the bill, if passed, would increase lynchings, “by leading the criminal to believe he would escape speedy death.” The only way to stop assaults, he declared, “is to let the negro know that when he is captured he will meet certain and immediate death.”10

Aswell’s argument is rife with doublespeak: he claims that lynchings would go up if they had more legal repercussions, and he uses both criminal and negro to describe the average lynching victim. He not only presumes that Black victims are typically criminals, but asserts that Blackness itself is criminal, that the “justice” of a lynching is always a kind of racial justice. So rather than tell white people not to lynch, Aswell says, simply remind Black people that they can be killed at any time: his proposed solution was to make assaulting a woman punishable by death, and “provide that the local courts must pass the death penalty 24 hours after the assaulter is caught.” Aswell reveals something that scholars like Saidiya Hartman might call fungibility: this quality that makes Black folks interchangeable in the white gaze, like stalks of corn, like grains of rice mingling in a breeze.11 He collapses every lynched body into one guilty Black man, a set of bones as soon as he’s named by a crowd.

Ultimately, past the Civil War, the plantation model may have been unsustainable for a host of reasons, natural, economic, social, and political—but it transformed into sharecropping and tenant farming, systems where the Black worker still owned practically nothing, and was tied to the field by debt. All three systems rested on the same basic premise: the dirt needs Black fingernails, and the white planter controls both.

Pessimism and Race

In 1919, the Great Migration was in full swing, and Black folks across the rural South were moving away from the old model—toward cities, or towards the North and Midwest. Many companies were opening industrial and desk-duty work to them for the first time, eager for the dirt-cheap labor that farm owners were already exploiting. This meant that some black farmers felt empowered to organize, to change how they could shape the South’s environment.

Let’s return, for a brief moment, to Vernon Parish, Louisiana. If you’ve ever wondered what Louisiana was like in the summer of 1919, when World War I still loomed ominously in the skyline to the east, I can tell you at least one thing for sure: it was rainy. So rainy, in fact, that Louisiana farms saw their harvests drop sharply. When a field agent from the US Bureau of Crop Estimates spread his regular update through local newspapers, he told reporters that the past month’s biggest crops were “pessimism and rice.”12 And even the rice was cause for concern: “while rice is in its glory,” you can read in the Vernon Parish Democrat, “it is true there has been too much rain even for rice, for the late planted varieties are not so good as they should be at this time, and the fields are weedy.”

What interests me more about this article, though, is the second reason the field agent gives for the sparse fields: Black folks. “Labor shortage is also a paramount issue. Negro farm help shows a positive unwillingness to work under pre-war conditions. There is a marked disposition to cling to the cities.”

These “pre-war conditions” aren’t spelled out directly, but they’re implied. Readers would have known that Black farmers routinely dealt with low wages, a lack of mobility, and the constant threat of violence. Now, Black folks demanded higher wages, threatening to move out of rural areas if they could get paid better in mines or warehouses. In the Chesterfield Advertiser, a South Carolina paper, a May 1919 column called “Success Talk to Farmers’ Boys” advised young white farmers that cotton prices would soar because of it:

Negroes are going into town industries. They know what wages they can get in West Virginia and Pennsylvania coal mines, in street work in Northern cities, or in railroad or factory work nearer home. Consequently the negro is coming to demand practically the same wages for farm work as he could get for town work, and will not make cotton unless he can get such wages. This means that in order to get enough cotton, cotton prices must go high enough to meet this expense.13

How many of us live where we do now because this exact scenario played out? My grandma’s family moved around the turn of the century—her grandma from the bootheel, her grandpa from somewhere in Tennessee. My grandpa grew up a sharecropper in Mississippi: he left school after the tenth grade to work on his family’s cotton farm. And in the 1940s, when they found out what the market rate for cotton was, they all left and came to St. Louis, where I grew up.

As for the black folks who stayed in the South, some of them actually pooled money to buy their own farms, like a group of black tenant farmers who spent $315,000 on a 4,200 acre tract in 1919 Mississippi.14 That’s over $4 million in 2020 dollars, by the way—and I’d guess that this price tag made white Southerners shudder. Landowning has always been a key sign of power in America: it’s the dream at the root of settler-colonialism. When many states joined the union, it was a requirement to vote. Landowners wrote the laws: they were the senators, governors, judges. So if Black folks could control the land, what else could they do?

Ownership of the Earth Forever and Ever

The Great Migration often gets framed as one big movement from Southern lowland to urban centers in the North. This framing is narrow, of course, as not everyone was moving North, and not everyone was moving to big cities. The Progressive Farmer and Southern Farm Gazette, a weekly that covered five Southern states, ran a front page article in the spring of 1910 about the plight of landless white farmers. Interestingly enough, they actually suggest that some Black folks buying land could be a good thing, or at least useful for the South’s economy. But the article insists that you can only have so many Black landowners before it’s dangerous:

It is as inevitable as fate that if any large proportion of the negroes acquire land… that these negroes will advance faster, attain to a higher standard of living, and acquire more influence, both politically and financially, than will the white men who remain mere renters, who have no home except by another man’s permission, and to whom the increase that comes in the price of life’s necessities, as the result of the increase in land values, will mean only harder times.15

I’d bet even the most “post-racial,” aviator-sunglasses-wearing, my-Twitter-account-is-my-first-name-and-a-bunch-of-numbers Americans know that the 1910s’ racists had no subtlety—why would they need it? But it’s fascinating to see them lay their cards out on the table when they were just speaking to each other. White Southerners set all the rules, deciding cotton prices, running banks that approved land purchases, making plows and tractors and bills. Even when they were poor, they telepathized every day what their Black peers could do and say and be. And yet, writings like the Gazette’s suggest that many of them felt deeply vulnerable. The anxiety makes me prick up right away, like a water drop falling from a ceiling into my hair. And I think about how anxiously they tied Blackness to the land: how they depended on it to keep the land’s worth, and hated that Black folks had our own sense of value. How much rural Black communities pined for a new relationship to the soil they wore away, the harvests they gave away, the open fields that gave their hiding places away.

For many Black folks, their link to the environment changed drastically: while buying acres in Alabama or Arkansas was a pipe dream, it was pretty much impossible in Chicago or Detroit. So, Black people in cities created new ecosystems, became part of the land in a new way—people like my great-great-grandfather Henry, who moved his family from a tiny town in southwestern Arkansas to East St. Louis, Illinois around 1905.

Starting in the late 1800s, East St. Louis’s politicians hoped to transform it from a farming town to an industrial suburb of St. Louis, just across the river. So close to the state line, companies could skirt Missouri regulations by building in Illinois, and the land was flat and cheap. The city was a blank slate for corporate development. By the time Henry arrived, it was stuffed with meatpacking, metalworking, chemical plants and refineries. And people could feel this new ecology in their throats: as historian Charles Lumpkins points out, these industries were “known for generating noxious air, water, noise, and olfactory pollution that damaged employees’ and residents’ health and homes.”16

If you look up Henry in the 1910 US Census, our family name misspelled; you’ll see that he was an engineer at a local steel plant. Almost all his neighbors worked there, too. I don’t know for sure which plant this was, but maps of the city’s old layout show one a few blocks away from his home. And surprisingly, much of his life would have felt integrated, at least for a little while. All his neighbors on the census page were white, for example: many were Hungarian and Polish, and had come to the United States just that year. On streetcars, segregation wasn’t strictly enforced, either—a white real estate agent complained that “black men would ‘jump in and get a seat beside a white woman,’ or they would ‘take all the seats by the window.’”17

Just as white farmers feared that Black folks would gain too much power over Southern fields, so white urbanites feared they would overrun the East St. Louis streets. They feared the Black workers that were popping up everywhere like kudzu. They feared the Black apartments that were remaking the city’s image. They feared climate change: they feared the loss of what Black studies professor Christina Sharpe calls the “pervasive climate of anti-blackness.”18 In her book In the Wake, Sharpe uses weather to explain how the aftermath of slavery lingers, always: “In what I am calling the weather, anti-blackness is pervasive as climate. The weather necessitates changeability and improvisation; it is the atmospheric condition of time and place; it produces new ecologies.” And so, when Black folks were changing East St. Louis, white folks adapted. They improvised.

—

It’s strange: describing the city this way feels like talking around it, because in 1917, my family left. Many people still don’t know what happened in East St. Louis that year, but I’ve known my whole life, because my family insists that we remember it.

Over a few days at the start of July, thousands of white people roamed the streets, beating, mutilating, and murdering any Black person they could find. They razed whole neighborhoods down to the curb. They dumped bodies in the opaque film of the river, let flaming rubble spread its embers in the wind like seeds. I won’t give graphic details—I think doing so focuses more on the spectacle of Black death than what it meant and why it happened—but the East St. Louis race riots were infamously gory, so gory that the National Guard was called in, and US Congress sent investigators to determine the cause. The news that week sounded utterly biblical. One Alaska paper forecasted that “the entire city was doomed to destruction.”19 The Kansas City Sun, a black weekly, egged its readers on to righteous anger: “Is God Dead? No! No! No!”20

But race riots were also meant to bottle the ecosystems of changing cities—to uproot Black weeds, and regrow white forests topped with white snow.

My great-grandfather, Henry’s son, was just 10 years old that summer. When he grew up, he only talked about East St. Louis after a few full glasses of whiskey. So I know a few things that he told my mom: that official reports massively undercounted the number of deaths; that his family’s home was set on fire and collapsed; that his grandfather was blind in one eye and didn’t make it out; that there were children who picked up guns and shot back to defend their people. Like thousands of others, my family ran to St. Louis and stayed there. Estimates from back then suggested that “more than half the black population left East St. Louis permanently.”21 What can I call them except refugees? What were they leaving except a natural disaster?

White rioters acted as if erasing the Black ecologies would save their own. Their testimonies, gathered by historian Malcolm McLaughlin, suggest this logic: “When rioters referred to their attacks as having ‘wiped out’ and ‘clean[ed] up’ neighborhoods, this may have reflected a feeling of having removed what they considered to be a ‘pollutant’ from their midst.”22 In the years prior, when black workers were flooding onto historically white blocks, city leaders boasted of plans to beautify downtown, to add a levee, a new sewer system, all things that would make it feel brighter and newer. A blacker city implicitly threatened those plans.

And McLaughlin notes something else that shocked me: a small, mostly-Black town called Brooklyn, just two miles north of East St. Louis, was left alone. Why? Maybe because it had been Black for a long time: it was actually founded by free Black folks and runaway slaves in the 1820s, and “was not associated with the recent changes.” For the rioters, it was okay to have Black people in their own enclave, far enough that it didn’t have to be seen or touched. It was contact that angered them. Vines crawling up their riverfront, the nagging thought of being replaced.

—

What does it mean to think of a race riot as ecoterrorism, violence with a distinctly environmental quality? White terror has routinely been used to protect America’s air of racial hierarchy. But race riots were also meant to bottle the ecosystems of changing cities—to uproot Black weeds, and regrow white forests topped with white snow. I can’t help but think of W. E. B. Du Bois, who visited East St. Louis as a reporter for the NAACP, and wrote about the city again in his 1920 book Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil. When Du Bois asks what whiteness is, why anyone would be so invested in it, the conclusion he draws is sobering. He says that “whiteness is the ownership of the earth forever and ever,” and I can see exactly what he means.23

No More Water, But Fire Next Time

“In the presence of negative peace.

By the time you finish theorizing, we’ll be dead in these streets…

I’ll come when you send for me. No more water, but fire next time.”

—Elucid

I’ll be honest—I hate the term “race riot.” I only use it here because it places East St. Louis in conversation with other white terror attacks that happened around the same time, in Chicago, Tulsa, Rosewood, Philly, Washington D.C., Baltimore, Knoxville, Charleston. In many cases, the term’s broadness obscures what those events actually were: massacres, preemptive strikes based on a false rhetoric of self-defense. And in 2020 we called uprisings in our cities “riots,” too, like they did in Watts and Newark in the 60s, as if the anger bubbling in those places was formless, like it’s an unthinkable response to the climate of state-sanctioned violence Black folks already live in.

Now, in two senses, the climate crisis is reaching a tipping point. I firmly believe that in the next few decades, we could experience another Great Migration: masses of people leaving the deep South and the East Coast as hurricanes and flooding become more frequent, as huge swaths of land become unlivable. It’s very possible that we fall into what some have called climate apartheid, where ruling classes have a monopoly on the planet’s shrinking resources, and government repression is used to protect them.24

You know what it makes me think of? For whatever reason, it makes me think about growing up on the north side of St. Louis, in a mostly-Black neighborhood the city always seemed to ignore. My mom and I lived around the corner from a sprawling old cemetery, where you can find the grave of William Tecumseh Sherman—the man who ordered towns and crops burned in the name of war, who left a throng of Black refugees behind him, trying to figure out what their freedom could mean. And one image keeps coming back to me from my childhood, as I drift off at night: the way some people on the north side set their lawns on fire, so the grass returns lusher, taller and greener.

I can’t help but wonder what saving us will mean. What can’t stay intact if we’re going to survive: the oil rigs and smokestacks, the police precincts and corporations, America’s ancient plantation, the wood rotting inside. What has to go up in smoke, so a Black planet might grow back.

—

Justin Davis is a writer and labor organizer. You can find his poems in places like Anomaly, wildness, Up the Staircase Quarterly, Apogee Journal, and Glass: A Journal of Poetry. You can find his essays in Labor Notes. He lives in Memphis, Tennessee. @AnkhDeLillo

Notes

- Che Gossett (@autotheoryqueen), “Living in the afterlife of slavery means living on the planetary afterlife of the plantation,” Twitter, August 31, 2020, 11:37 a.m., https://twitter.com/cruisingatopia/status/1300457645455880192.

- United States Census Bureau, 1860 Census: Statistics of the United States, Including Mortality, Property, Etc. (Washington, 1866), https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1866/dec/1860d.html.

- Martin Ruef, “The Demise of an Organizational Form: Emancipation and Plantation Agriculture in the American South, 1860–1880,” American Journal of Sociology 109, no. 6 (May 2004): 1365–1410, https://doi.org/10.1086/381772.

- “A Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union.” Avalon Project, Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library, accessed April 25, 2022, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_missec.asp.

- Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 10.

- Mbembe, Necropolitics, 10.

- Carolyn Merchant, American Environmental History: An Introduction (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 50.

- Monique Allewaert, Ariel’s Ecology: Plantations, Personhood, and Colonialism in the American Tropics (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 33.

- Frederick Douglass, The Claims of the Negro, Ethnologically Considered: An Address Before the Literary Societies of Western Reserve College, at Commencement, July 12, 1854 (Rochester, NY: Lee, Mann & Co.: 1854).

- “Aswell Fights Anti-Lynching Bill in U.S. Congress,” Vernon Parish Democrat, December 22, 1919.

- Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- “Louisiana Crops Are Unimproved,” Vernon Parish Democrat, August 30, 1919.

- Clarence Poe, “Success Talk to Farmers’ Boys.” The Chesterfield Advertiser, May 22, 1919.

- “Negro Tenant Farmers Purchase Large Tract,” The Dallas Express, November 8, 1919.

- “The Chances of the Landless Man,” The Progressive Farmer and Southern Farm Gazette, May 28, 1910.

- Charles L. Lumpkins, American Pogrom: the East St. Louis Race Riot and Black Politics (Ohio University Press, 2008).

- Malcolm McLaughlin, Power, Community, and Racial Killing in East St. Louis (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

- Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: on Blackness and Being (Duke University Press, 2016).

- “Hundreds Slain in Illinois Town Riot,” Valdez Daily Prospector, July 5, 1917.

- “Fiends Incarnate! Cowardly Police and Militia Search Negroe’s Homes, Disarm Them, and Then Turn Them Over to the Blood-Thirsty Demons Clamoring for Their Lives,” The Kansas City Sun, July 7, 1917.

- Lumpkins, American Pogrom.

- McLaughlin, Power, Community, and Racial Killing in East St. Louis.

- W. E. B. Du Bois, Darkwater: Voices from within the Veil (Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920).

- “UN Expert Condemns Failure to Address Impact of Climate Change on Poverty,” United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, October 5, 2020, www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24735.